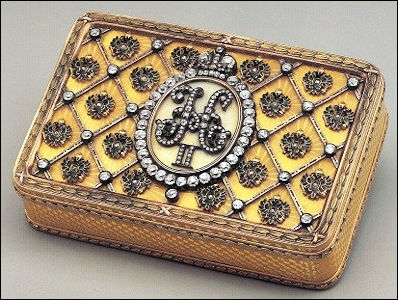

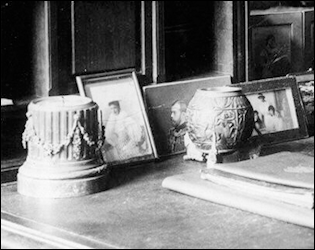

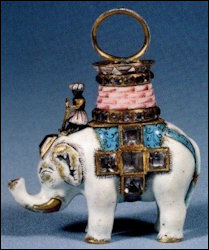

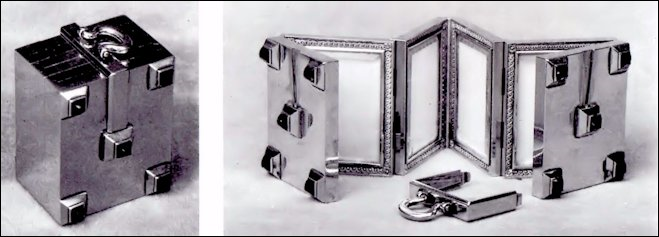

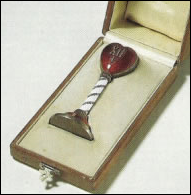

Presentation Snuff Box before 1896, Workmaster: August Holmström

Scratched Stock no. 1067 (Cost 1,300 rubles, $970 at the Time, $28,992 in 2017)

(Courtesy Forbes Magazine Collection)

Recipient of the Gift:

Lieutenant-General Baron

Arthur von Bolfras, Chief

of the Military Chancellery

of the Austrian Kaiser

Franz Joseph I

(© Bildarchiv Austria, ÖNB)

Emperors Nicholas II and Franz Joseph I on Review, 1897

(Wiki)

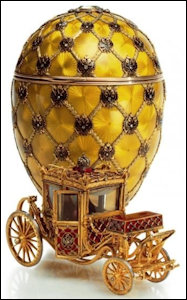

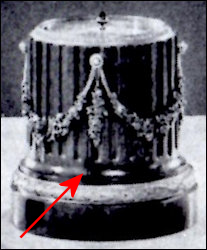

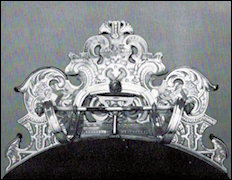

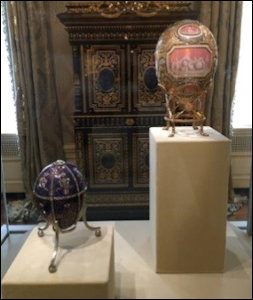

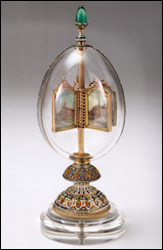

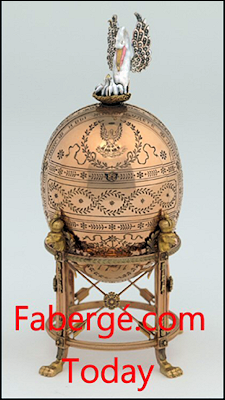

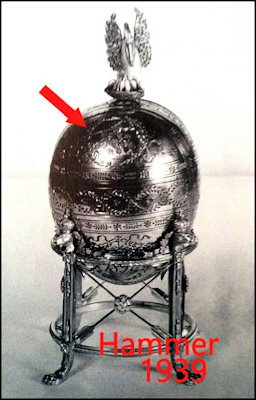

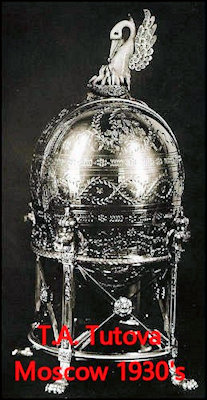

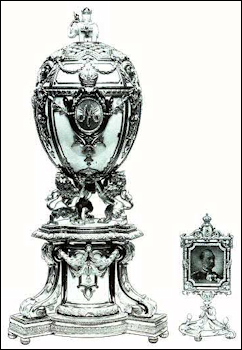

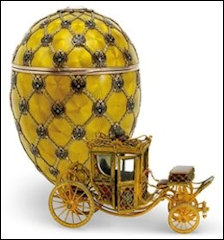

1897 Coronation Egg,

Workmaster: Mikhail Perkhin

Assistant: Henrik Wigström

Miniature by Georg Stein

Marks: M. P. in Cyrillic, 56,

crossed anchors and scepter,

Wigström roughly scratched on

inner surface of shell, pre-1899

assay mark (Cost 5,500 rubles,

$2,835 at the Time, $87,734 in 2017)

(Courtesy Fabergé Museum,

St. Petersburg, Russia)

1896 Coronation of Russian Emperor Nicholas II,

Oil Painting by Laurits Tuxen, 1898

(Courtesy, Hermitage Museum)

- The Imperial presentation snuff box was made in the August Holmström workshop and the egg in the Mikhail Perkhin workshop. Over the years, the objects have been incorrectly identified with their workmasters. For example, in the 1949 Wartski loan exhibition the snuff box was attributed incorrectly to Perkhin and then again in 2005 by Tillander-Godenhielm, and in 2017 by the current owner, the Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. (Endnotes 1, 4, 8)

- The snuff box was made before 1896, and the Coronation Egg, 1896-1897.

- The above gifts were presented by Nicholas II to an Austrian military officer and to Alexandra Feodorovna, the wife of a Russian emperor.

Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm in 2005 and Valentin Skurlov in 20171 state the snuff box, intended as an official imperial award, was “presented to Lieutenant-General Baron Arthur von Bolfras during the state visit of Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria to St. Petersburg in 1897”.

Tillander-Godenhielm notes the officials of the Cabinet of His Imperial Majesty, who selected diplomatic gifts from their stock, were advised of the value it was to have (in this instance 1,300 rubles), and a gift was chosen solely based on such criteria. Considerations with regard to the design of the gift appear not to have been as important as the monetary value of it. Had the design been considered, this Imperial presentation snuff box would have been more suitable as a gift to a highly-ranked Russian official who had assisted in the preparations for the 1896 coronation rather than a foreign dignitary.

Chronology of gifts:

- Snuff box by August Holmström (active 1829-1903) made before 1896, and presented to Baron Arthur von Bolfras in either January or March of 1897, when he accompanied the Austrian Kaiser Franz Joseph I on a state visit with Nicholas II in St. Petersburg.

- The Coronation of Nicholas took place on May 26, 1896, and the Fabergé Egg by Mikhail Perkhin (active 1860-1903) was presented a year later at Easter on April 18, 1897, to Empress Alexandra Feodorovna.

Kenneth Snowman2, proprietor of Wartski in London, records a conversation with George Stein on how the trellis of eagles are fixed on the enameled surface of the Coronation Egg by submerging the object into a tank of water. George Stein, a master carriage builder by profession, was hired by Fabergé in 1896 to work in the Perkhin studio and is credited with making the carriage surprise for the 1897 Coronation Egg.

In their catalogue raisonné the Forbes Magazine Collection3, which acquired the snuff box in 1966, published a list of owners from 1937/38 to 1999. When available, confirming literature citations have been added to the Forbes chronology by this author. Observations shared by Valentin Skurlov4 in a chapter published in the 2017 book by the Fabergé Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia, are added in brackets [ ].

- Private collection, Vienna and Herr Bomm, Vienna [Skurlov suggests “the box was acquired from a Mr. Bomm in 1937 – some sources give 1938 – by Alexander Schaffer. Allegedly Mr. Bomm had bought it from a Russian émigré journalist. This sounds like an assumption without documentation – it was more likely that the Austrian general heirs sold the snuff box.”] According to the Forbes Magazine Collection exhibition catalog for the 1973 New York Cultural Center venue the sequence is described thusly, “A Russian émigré living in Vienna from whom it was purchased by Mr. Hill of Berry-Hill Galleries in 1938. He subsequently sold it to Messrs. Wartski, who owns the Coronation Egg.”5

- Sidney Hill, Berry-Hill Galleries, London and New York. Advertisement in Connoisseur, December 1937, indicates the box is for sale from this dealer.6

- Wartski, London, and Arthur E. Bradshaw, prolific British collector, who owned both the Coronation Egg and the Imperial presentation snuff box, are discussed in Geoffrey Munn’s book (see footnote 7). Bradshaw bought both objects from Wartski between 1935 until his pre-mature death in October 1939. A Bradshaw collection inventory by Wartski confirms he owned the box in 1938.7

- Wartski 1949 Exhibition.8 Object 269 lent courtesy of the Collection of Messrs. Wartski.

- In 1961, the Corcoran Gallery of Art9 in Washington (DC) displayed a private Fabergé collection – Lansdell Christie – and A La Vieille Russie10 in an exhibition has the same illustration in its 1961 exhibition catalog.

- The box with the same photograph is illustrated in a 1962 book by Kenneth Snowman with the note, “In a private collection in the United States.”11

- Lansdell K. Christie, Long Island New York. The object is illustrated and included by Snowman for a chapter about the Christie’s collection.12 The author says …”the box must have caused Nicholas II to catch his breath when he received it as a coronation gift from the hand of his Tsarina, Alexandra Feodorovna.” (It is now known archival documentation found by Valentin Skurlov in the Russian State Historical Archives (RGIA), St. Petersburg, proves the recipient of the Imperial presentation box was Lieutenant-General Baron Arthur von Bolfras.)

- On loan to the Metropolitan Museum in New York City from 1962-1966.

- A La Vieille Russie, New York, dealer acquired privately some of the Fabergé Collection from the estate of the late Lansdell Christie.

- Forbes Magazine Collection, New York, Accession No. Fab 66009 confirms the Imperial presentation snuff box sold to Forbes in 1966. [Skurlov states “Malcolm Forbes bought it at Christie’s Geneva, on May 2, 1978.”] Author of this essay is not able to find an auction catalog with this date. The Coronation Egg – Accession No. Fab 79002 – was acquired privately by Malcolm Forbes in 1979 from Wartski along with the Lilies of the Valley Egg.

- [The presentation snuff box was first shown in Russia in 1990 at the San Diego-Moscow Exhibition along the side of the Coronation Egg.] It is not shown in the English or the Russian exhibition catalogs.

- Viktor Vekselberg acquired both the Coronation Egg and the Imperial presentation snuff box in 2004, and they are now beautifully displayed in the Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia.

At the 2011 Rome (Italy) exhibition, Vatican – Fabergé Eggs13, the snuff box is perhaps for the first time identified as a presentation piece given to Lieutenant-General Baron Arthur von Bolfras during the state visit of Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria to St. Petersburg, 1897.

Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm after reviewing this research posed an additional – as yet unanswered – hypothesis:

- Due to archival documentation14, there is water-tight information the snuff box was an official Imperial presentation gift.

- In advance of producing the 1914 Mosaic Egg the Holmström workshop made prototypes (at least two of them) in order to check if the technique they planned to use ‘worked’. This snuffbox could also have been such a prototype, which upon completion was transferred to the stock of the Imperial Cabinet, and used when a gift of a certain monetary value was needed for an Imperial presentation.

1Tillander-Godenhiem, Ulla. The Russian Imperial Award System during the Reign of Nicholas II, 1894 – 1917, published in 2005, p. 180.; Skurlov, Valentin, “Imperial & Cabinet Gifts” in Fabergé: Treasures of Imperial Russia – Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg, 2017, pp. 82-83, 89. Both authors suggest the workmaster is Mikhail Perkhin, but should be August Holmström (active 1880-1913).

2Snowman, A. Kenneth. The Art of Carl Fabergé,1st edition, 1953, p.52.

3Forbes, Christopher, and Robyn Tromeur-Brenner. Fabergé: The Forbes Collection, 1999, pp. 40-41, 271.

4Skurlov, Valentin, “Imperial & Cabinet Gifts” in Fabergé: Treasures of Imperial Russia – Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg, 2017, pp. 82-83, 89.

5Waterfield, Hermione. Fabergé: The Forbes Magazine Collection, 1973, p. 52-53.

6McCanless, Christel Ludewig. Fabergé and His Works, An Annotated Bibliography of the First Century of His Art, 1994, entry #106.

7Munn, Geoffrey. Wartski – The First One Hundred and Fifty Years, 2015, pp. 236-240; confirmed in email communication with Jane Allen, Bradshaw biographer and a relative of the late collector.

8Wartski, A Loan Exhibition of the Works of Carl Fabergé … November 8-25th, 1949, pp. 4, 22, workmaster misidentified as Perkhin on p. 22. The details about the exhibition catalog in endnote 3 above (Forbes 1999, p. 271), are incorrect and lead to a different box lent by Her Majesty the Queen of England.

9Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington (DC). Easter Eggs and Other Precious Objects by Fabergé: A Private Collection of Masterworks Made for the Imperial Russian Court, 1961, frontispiece, p. 33

10A La Vieille Russie, New York. The Art of Peter Carl Fabergé, A Loan Exhibition…, 1961, pp. 43, 49.

11Snowman, A. Kenneth. The Art of Carl Fabergé, 2nd edition, 1962, colored frontispiece illustration matches endnotes 9-10.

12Snowman, A. Kenneth in “Great Private Collections”, 1963, pp. 244-245.

13Vatican exhibition details courtesy of Jane Allen, Australia.

14Not published at this time.

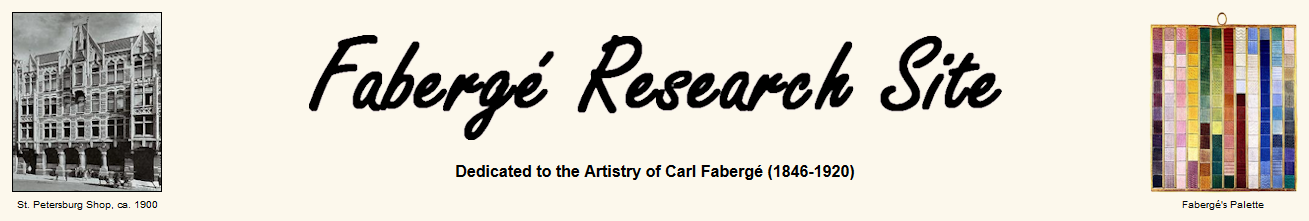

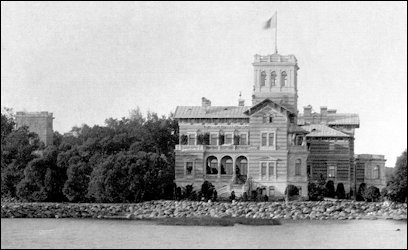

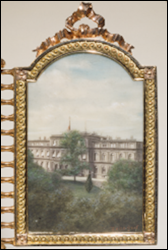

Lower Dacha of Emperor Nicholas II in Alexandria Park in Peterhof, Russia,

View from the Gulf of Finland, Photograph 1905-1915

(Both Photographs are First Publications1, Courtesy, Peterhof Museum Complex)

Minshall Fabergé Barometer without

the Central Pendant

(Courtesy Cleveland Museum of Art)

Workmaster Viktor Aarne in His Finnish Studio after 1904

(Courtesy Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm)

History of Lower Dacha, Alexandria

A four-story palace, sometimes called the New Palace was located on the shore of the Gulf of Finland, in the northeast corner of the Alexandria Park in Peterhof. It was built in the 1890s. The building, resembling an Italian villa, was built of yellow and red brick, decorated with a tall tower and a viewing platform, and featured interiors decorated in Art Nouveau style. On August 12 (Old Style July 30), 1904, the only son of Emperor Nicholas II and Empress Alexandra, Alexei was born there [as well as daughters Maria in 1899 and Anastasia in 1901]. Here the Emperor signed the manifesto on Russia’s entry into the First World War. After 1917, the palace became a museum, and then a boarding house of the NKVD [secret police]. During the war damage occurred and in 1961 the remains of the building were blown up by the Soviet government. The need for emergency response was evident after the dismantling of the ruins in June-September 2016, when fragments of walls, decor, and floors of the ground floor of the “House” were found under the debris. The contractor’s tasks include the construction of a temporary protective canopy over the surviving structures. (Romanov News, #119, February 2018, p. 33)

Recent publications about the restoration project of the Lower Dacha:

- Ludmila and Paul Kulikovsky, Editors, “Great Architecture Can Only Be Royal”, Interview with Denis E. Rieder, St. Petersburg Designer and Architect about Future Plans for the Dacha published in Romanov News, #119, February 2018, pp. 30-33.

- Gilbert, Paul, “First Tourist Group Visits Lower Dacha of Nicholas II in Peterhof”. (Royal Russia News, May 2, 2018).

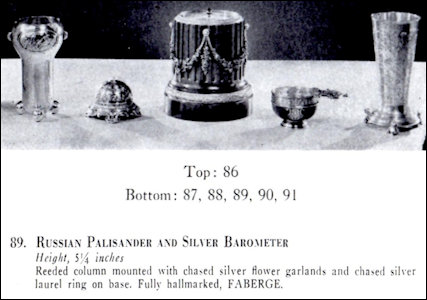

History of the Barometer

Extant archival documents are a researcher’s treasure trove, but until such time as Peterhof Palace inventories are found, a variety of other research tools were used.

- Cleveland website description (The India Early Minshall Collection 1966.484): Barometer, 1896-1903 by Peter Carl Fabergé (Russian, 1846-1920), palisander, silver gilt, garnet, overall: 14 x 12.5 cm (5 1/2 x 4 7/8 in.)

- Henry Hawley, Associate Curator of Decorative Arts at the CMA2, identified in 1967 Johan Viktor Aarne (BA or J.V.A.) as the workmaster, and ЛЯ as the assay master [Jakov Ljapunov, active in St. Petersburg 1898-19043]. Research has updated Aarne’s biographical data in the intervening 50 years. The attribution of the Nicholas Equestrian Egg [now considered to be a fake by scholars] to Aarne in 1913 is not correct, since Aarne was no longer working in Russia.

- Lowes and McCanless4 in 2001 state Viktor Aarne (1863-1935), using the marks J.V.A [only for use in Finland] and BA

was active in St. Petersburg from 1891-1904. During a period of ca. 13 years he produced an enormous amount of objects for the Fabergé firm.5 He sold his workshop, which employed 20 journeymen and three apprentices, to Hjalmar Armfelt, another Fabergé workmaster, and returned to Vyborg (Viipuri, then part of Finland) to establish a workshop and a thriving retail business.

was active in St. Petersburg from 1891-1904. During a period of ca. 13 years he produced an enormous amount of objects for the Fabergé firm.5 He sold his workshop, which employed 20 journeymen and three apprentices, to Hjalmar Armfelt, another Fabergé workmaster, and returned to Vyborg (Viipuri, then part of Finland) to establish a workshop and a thriving retail business.

Therefore, the barometer can be dated prior to 1904 since two events occurred in St. Petersburg: Aarne sold his workshop and Jakov Ljapunov died in March. Eventually a timeline evolved in our research:

May 5-6, 1901 Another possibility (as yet unconfirmed) exists, was it a gift from Empresses Alexandra or Marie Feodorovna, or a member of the Imperial family? James Hurtt reviewed lists of Fabergé objects purchased by the immediate Imperial family (Emperors Alexander III, Nicholas II, Empresses Maria Feodorovna and Alexandra Feodorovna, Grand Duchesses Olga and Xenia, and Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich). Only three barometers were purchased by one of these august personages from 1887-1916. The Minshall barometer in this study is made from wood and silver in a late 18th century design ruling out the nephrite and red enamel example purchased by Nicholas himself in 1899, and the red enamel one purchased by Empress Maria Feodorovna. However, there is a likely match with the one purchased by Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich (brother of Nicholas) on May 5, 1901 (OS), the day before his brother’s 33rd birthday (born May 6, 1868). The invoice states, “Silver, Wood, Louis XVI Style with garnet” barometer with a stock of 4462 costing 160 rubles, or a little less than what a grammar school teacher in Russia (or even in the U.S. at that time made in an equivalent salary) for two months of teaching.

(Guzanov, A. and R.R. Gafifulin, Fabergé Items of Late XIX – Early XX Century in the Collection of the State Museum Pavlovsk, 2013, p. 171)

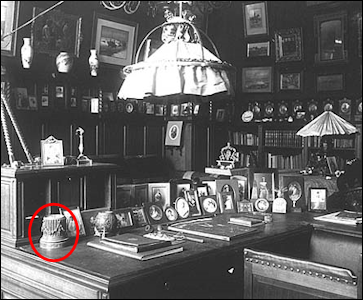

1901-1917 Nicholas treasured the barometer on his desk at the Lower Dacha.

1933-1934 Historical Rooms in the Lower Dacha, Peterhof Palace, were closed6 and there was a “transfer of property to Tsarkoye Selo”. Some items were moved to the Alexander Palace in Tsarkoye Selo where the barometer is seen on Nicholas’ desk in his New Study/Working Study7 in the 1930’s.

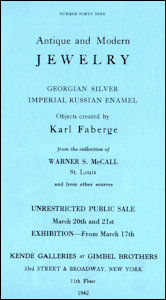

March 20-21, 1942 Kende Galleries at Gimbel Brothers in New York City offered the barometer as Lot 89, a Russian palisander and silver barometer. A priced catalog records the barometer sold for $37.50 (2018 equivalent $580). An inventory card in the CMA curatorial files includes an inscription, “20/Barometer/Hammer”, possibly written by Henry Hawley.8 The text matches item No. 20. Barometer. 66.484 shown in the 1967 Cleveland museum catalog, and points toward Mrs. Minshall’s purchase from Armand Hammer, the dealer from whom she obtained other Fabergé objects. No known invoice is extant.

1965 Prior to Mrs. Minshall’s death that year, a privately printed presentation copy, slip-cased and leather bound with loose color plates for each object shows the barometer, complete with its decoration only applied on the front side. The lavish publication documents the entire collection, and is now part of the Ingalls Library’s Rare Book Collection.

2015 Stephen Harrison, curator at the Cleveland Museum of Art, in an examination of the barometer in its display case at the museum observed these details:

1930’s New Study

(Tsarskoye Selo

State Museum-Preserve)

1942 Kende Galleries

(McCanless Collection)

1965 Minshall Album

(Cleveland Museum of Art)

2008 CMA Postcard

(McCanless Collection)

1Archival photographs published for the first time in Nicholas II: The Imperial Family published for the 300th Anniversary of Peterhof, 1705-2005, Arbis Publishers, 2004, pp. 39 and 43. A photograph album by Nigel Fowler Sutton entitled Нижняя дача, Петергоф / Lower Dacha, Peterhof (1885-1961) appeared on the internet (March 30, 2017), with the same photographs and a brief introduction for each section without credits. At the end of the video the remaining ruins of the dacha are shown.

2Fabergé and His Contemporaries, 1967, Object No. 20, Barometer.

3Jakov Ljapunov died on March 28, 1904 (Skurlov, Valentin. “Russian Hallmarks at the Turn of the 19th Century” in Géza von Habsburg, Fabergé, Imperial Craftsman and His World, 2000, pp. 404-405.)

4Fabergé Eggs: A Retrospective Encyclopedia, 2001, p. 178.

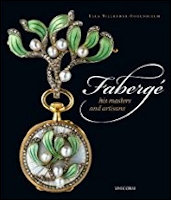

5Tillander-Godenhielm, Ulla. Fabergé. His Masters and Artisans, 2018, pp. 195-204.

6Gafifullin, Rifat, “Sales of Works from the Leningrad Palace Museums, 1926-1934” in Odom, Anne and Wendy R. Salmond, Treasures into Tractors, 2009, p. 151, footnote 54 on pp. 163-164.

7The New Study in the Alexander Palace, Tsarskoye Selo, was built in 1902 by Roman Meltzer in a major project to enlarge the living quarters of the Imperial family. Two large rooms, the Maple Room and the New Study were built on opposite sides of an extension of the corridor, but with a lower ceiling to accommodate a mezzanine level which connected the balconies of the two rooms.

8Priced catalog in possession of the Ingalls Library and Museum Archives. Details courtesy of Louis Adrean, CMA.

Queen Wilhelmina Nephrite Tray by Fabergé, 13 1/4 in. (34 cm.) Long

(Christie’s London and Tillander-Godenhielm, Ulla,

et al. Carl Fabergé and His Contemporaries, 1980, p. 19)

View of the Decorated Red Gold Handles from the Top and the Underside

(Courtesy Tillander-Godenhielm, Ibid., and The Connoisseur, June 1962, p. 99)

Christie’s1 described the presentation tray in 1980:

Fabergé Eggs

(Courtesy Virginia Museum of Fine Arts)

Fabergé Eggs at Hillwood Museum

(Courtesy of George W. Terrell, Jr.)

Visiting Fabergé Eggs in the

Fabergé Rediscovered Venue at Hillwood Museum,

(Prince Albert II Collection1, Monaco;

Fondation Edouard et Maurice Sandoz2)

1Munn, Geoffrey, “The Rediscovery of the Serpent Egg Clock”, Fabergé Research Newsletter, November 2008.

2Elizabeth Doerr, “Parmigiani Fleurier and the Yusupov Fabergé Egg of 1907”, Quill&Pad, April 1, 2018.

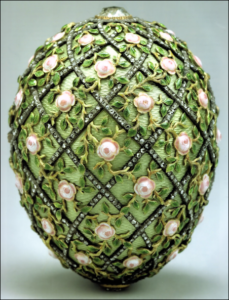

| # | LADY'S CHOICE - CAROL W. | GENTLEMAN'S CHOICE - BOB D. |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Winter Egg | Winter Egg |

| 2 | Peacock Egg | Coronation Egg |

| 3 | Mosaic Egg | Catherine the Great Egg |

| 4 | Alexander Palace Egg | Lilies of the Valley Egg |

| 5 | Trans-Siberian Railway Egg | Mosaic Egg |

| 6 | Clover Leaf Egg | Romanov Tercentenary Egg |

| 7 | 15th Anniversary Egg | Clover Leaf Egg |

| 8 | Gatchina Palace Egg | 15th Anniversary Egg |

| 9 | Standart Egg | Pelican Egg |

| 10 | Diamond Trellis Egg | Cockerel Egg |

In the last 20 years two books about Imperial Easter eggs and their surprises made by the Russian court jeweler Fabergé were published:

- Faberge, Tatiana, Proler, Lynette G. and Valentin V. Skurlov. The Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs, 1997. Letters written by Tsars Alexander III and Nicholas II, Fabergé invoices, cabinet documents and Bolshevik inventories are the basis for new research by Valentin V. Skurlov of St. Petersburg. This information sheds new light on the history of the Fabergé eggs.

- Lowes, Will, and Christel Ludewig McCanless. Fabergé Eggs: A Retrospective Encyclopedia, 2001. Monograph gives comprehensive information about 66 Fabergé eggs divided into four categories – Tsar Imperial, Imperial, Kelch and Other. Technical descriptions, all known public exhibitions and auctions through 1997, and reference citations (books, journals, newspapers, and miscellaneous sources) covering the literature of nine countries are given for each egg. Who’s Who in the House of Fabergé profiles 500 artisans and companies who worked for or with Fabergé.

New findings about missing eggs and their surprises are featured on two complimentary Fabergé websites:

- Fabergé Research Site, edited and published by Christel Ludewig McCanless, includes ongoing research in its quarterly Fabergé Research Newsletter with an Index to the Eggs. The Imperial Egg Chronology was updated by Will Lowes from the 2001 publication cited above.

- Mieks Fabergé Eggs, edited and published by Annemiek Wintraecken, has current research in both Dutch and English.

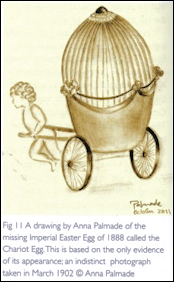

Amazing detective work has been spearheaded by Annemiek Wintraecken (Netherlands) with her website, Wartski’s Kieran McCarthy in the firm’s archives and in British newspapers, Anna & Vincent Palmade (USA), and with the interaction of Fabergé Research Newsletter readers. Wintraecken and the Palmade’s have studied in detail archival photographs from exhibitions held during the life time of Carl Fabergé (1846-1920), and more.

Mieks Fabergé Eggs:

- 1900 Paris Exposition Universelle, France The 1900 Paris Exposition Universelle, France

- The 1902 Von Dervis Fabergé Exhibition of Objets d’Art and Miniatures, Saint Petersburg, Russia

- 1937 Armand Hammer Galleries, “A $1,000,000 Worth of Easter Eggs“

Fabergé Research Newsletter (FRN):

- Paris Exposition Universelle/World’s Fair (1900) 04.08 | 08.08 | Winter 08-09 | Summer 14 | Spring and Summer 17

- von Dervis Exhibition (1902) Eggs | 04.08 (Anniversary Edition) | Winter 08-09 | Spring 11 | Summer 14 | Spring and Summer 17 (also cited as von Derviews)

(Fabergé Research Site | Mieks Fabergé Eggs)

Egg Unknown

(Fabergé Research Site | Mieks Fabergé Eggs)

Lot 259

(Courtesy Parke Bernet)

(Courtesy Wartski)

CLICK THE ABOVE PICTURE FOR A LARGER VIEW

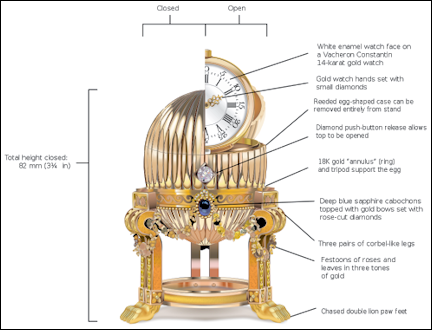

Diagram of the Third Imperial Egg

(By KDS4444 – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0 on Wiki)

2014: Kieran McCarthy of the London jewelry firm Wartski authenticated and bought the egg from a scrap dealer in the USA. The current whereabouts of the egg and the clock surprise are unknown.

September 2017: A diagram of the Third Imperial Egg shown half open and half closed at the same time with complete technical details appeared in Wikipedia.

(Fabergé Research Site | Mieks Fabergé Eggs)

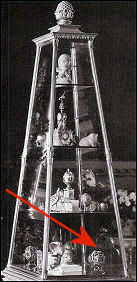

Maria Feodorovna Vitrine in

von Dervis 1902 Exhibition

1888 Cherub Egg with Chariot Reflection

(Archival Photographs)

Palmade Drawing in 2011

(Fabergé Research Site | Mieks Fabergé Eggs)

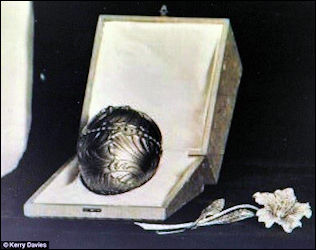

Nécessaire Egg and Kellie Bond

(Courtesy Daily Mail, UK)

(Fabergé Research Site | Mieks Fabergé Eggs)

Archival Photograph,

Egg with Stand, Now Missing

(Sotheby’s, December 5, 1960, Lot 92

sold for £2400; Courtesy Annemiek Wintraecken)

OOOPS! Upside Down Fabergé Egg!

(Houston Museum of Natural

Science News, March/April 2018)

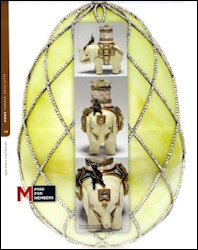

Egg Reunited with the Missing

Elephant Automaton Surprise Which Originally

Resided in the Larger Half of the Egg

(Courtesy Dorothy and Artie McFerrin

Collection and Royal Collection

Trust Her Majesty

Queen Elizabeth II, 2015)

Insignia, Order of the

Elephant with Christian VI’s

(1699-1746) Monogram, the

“Baroque Version” Used

throughout the 18th Century.

(Why the Elephant?

Mini-Guide Published in

Association with Rosenborg

Castle, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2015)

(Fabergé Research Site | Mieks Fabergé Eggs)

(Courtesy Hillwood Estate,

Museum and Gardens)

Missing Folding Miniature Frame Surprise without Alexander III Miniatures by Zehngraf

(Snowman, A. Kenneth, Carl Fabergé, Goldsmith to the Imperial Court of Russia, 1979, 56)

(Fabergé Research Site | Mieks Fabergé Eggs)

Neues Palais, Darmstadt, Germany

(Courtesy Virginia Museum of Fine Arts)

(Fabergé Research Site | Mieks Fabergé Eggs)

1897 Mauve Egg Surprise (3 1/4 in., 8.3 cm.)

(Forbes, Christopher, and Robyn

Tromeur-Brenner, Fabergé: The Forbes

Collection, 1999, pp. 42-45; Egg Surprise

in the Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia)

1896 Fabergé Miniature (4 1/2 in., 11.5 cm.)

in a 1997 Stockholm Exhibition

(Welander-Berggren, Elsebeth, Carl Fabergé:

Goldsmith to the Tsar, 1997, p. 161,

Photographs © Erik Cornelius, National Museum Stockholm)

- Does the strawberry red or scarlet color of the frame really blend with the mauve enamel Egg description, and is the suggested surprise frame indeed part of the lost egg?

- Another observation which is even more puzzling – would Fabergé have repeated a similar design concept in a smaller version for the Mauve Egg presented to the Empress in 1897?

(Fabergé Research Site | Mieks Fabergé Eggs)

Pelican Egg Collage

(Courtesy Annemiek Wintraecken and Virginia Museum of Fine Arts)

(Fabergé Research Site | Mieks Fabergé Eggs)

(Muntian, Tatiana N. Fabergé.

Easter Gifts, 2003, pp. 36-39)

Clover Leaf Egg Surprise

Alexandra Feodrovna and Nicholas II, 1908

(Courtesy Annemiek Wintraecken)

(Fabergé Research Site | Mieks Fabergé Eggs)

Egg Unknown

(Fabergé Research Site | Mieks Fabergé Eggs)

Missing Egg

(Courtesy Tatiana Faberge Archives)

(Fabergé Research Site | Mieks Fabergé Eggs)

(Tillander-Godenhielm,

Fabergén suomalaiset mestarit,

2011, p. 131)

Rose Trellis Egg Surprise

Alexandra Feodrovna, 1908

(Courtesy Annemiek Wintraecken)

(Fabergé Research Site | Mieks Fabergé Eggs)

Missing Egg

(Courtesy Tatiana Fabergé Archives)

The Fabergé Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia, began sponsoring annual symposiums in 2014. Scholarly research summaries of the papers presented at these events have been published in the Fabergé Research Newsletter and in paperback format by the museum. Readers should be aware the paperback for a given year is published a year after the actual symposium. A compilation of the summary proceedings in English and Russian are listed below.

2014 1st Conference in Russia (3rd Gathering of Fabergé enthusiasts): The World of Fabergé in St. Petersburg 100 Years Ago

- Fabergé Research Newsletter, Fall 2014

- A summary in English and Russian of the presentations was published.

- Tim Adams, Christel McCanless and Annemiek Wintraecken, Windows into Russian Life: Fabergé’s Hardstone Figures, share extra details in an illustrated summary from their presentation. More…

2015 Symposium Lapidary Art

(Paperback Published in 2016)

2016 Symposium 170th Anniversary

of the Birth of Carl Fabergé, 1946-1920

(Karina Pronitcheva, Fabergé Museum

kindly shared these details.)

2017 Symposium Aquamarine Necklace

by Fabergé

(Courtesy Alexander von Solodkoff)

- Day One Proceedings

- Day Two Proceedings

- East Meets West: Russian Hardstones and the British Royal Collection, a recording of the public lecture by Caroline de Guitaut unveils the missing elephant automaton surprise.

- Korneva, Galina, and Tatiana Cheboksarova, Academic Editors, et al. Materials from the International Academic Conference at the Fabergé Museum in St. Petersburg: Lapidary Art contains Russian and English summaries of the symposium presentations.

2016 3rd Conference: 170th Anniversary of the Birth of Carl Fabergé (1946-1920)

- October 6, 2016 Proceedings in Russian

- October 7, 2016 Proceedings in Russian

- Riana Benko from Slovenia compiled Fabergé Symposium Summaries, St. Petersburg, 2016, in English.

- 2017 publication contains Russian and English summaries of the 2016 symposium presentations.

2017 4th Conference: Russian Jewelry Art of the 19th and Early 20th Centuries in a Global Context. Conference summaries in a paperback to be published later in 2018.

Alexander von Solodkoff, independent researcher from Germany, kindly shared a review of his research from the 2017 event. His topic related to fashion and jewelry in St. Petersburg around 1900, the use of aquamarines by Fabergé, his parure for Grand Duchess Elisabeth and the discovery of a commission from Fabergé for an aquamarine tiara in 1904. Fashion for ladies’ dresses changed significantly during the Belle Époque between 1890 and 1914 from heavy embroidered velvet to lighter silk chiffon dresses. The colors shifted from dark to pastel, for example, from burgundy red or emerald green to pale mauve or sky blue. Jewelry followed this fashion by becoming more subtle and colorful.

Fabergé insisted on his preference to produce artistic jewelry as opposed to parures of diamonds, rubies, sapphires and emeralds consisting only of large stones of very high value. His emphasis was on colored semi-precious stones such as amethysts, citrines, mecca-stones, topazes or aquamarines. A considerable quantity of Fabergé jewels were Russian aquamarines from the Urals mounted in diamond settings. A complete aquamarine parure was made for Grand Duchess Elisabeth, the sister of the Empress, a very fashion-conscious lady. Her aquamarine jewels including a necklace, earrings and tiara survived and was last seen at an auction in 1996. Following this fashion a similar tiara was ordered from Fabergé by a member of a German ruling family in 1904. The hitherto unpublished correspondence with Fabergé detailing the production, choice of stones and price was recently discovered in a German State Archive. It was presented here for the first time with photographs of the original recipient of the jewel wearing the aquamarine and diamond tiara.

2018 5th International Academic Conference, September 20-22 in St. Petersburg, Russia

The Carl Fabergé Memorial Rooms, a permanent display in the General Staff Building on Palace Square in St. Petersburg serves as an annex to the Hermitage Museum. Marina Lopato, Senior Curator at the State Hermitage Museum, has alerted readers to a virtual tour (reload the link if you do not start in a room with red walls | the complete tour map will help guide you through the building if needed) allowing you to view three rooms full of Fabergé objects complete with close-ups and Russian didactic texts.

1991 Fabergé Design Sketches from

the Hermitage Archives Viewed by

Kenneth Snowman, Marina

Lopato, and Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm

(Photograph Courtesy of

Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm)

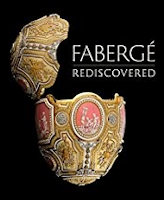

Hillwood Exhibition Catalog:

Zeisler, Wilfried, et al.,

Fabergé Rediscovered

(Publication June 2018)

- Hillwood’s new website has a plethora of events for all ages makes a visit to the museum and gardens worthwhile.

- Fabergé object database is accessible via the web.

- Hillwood videos: Chesapeake Collectibles begins @11:50, and Why this American Cereal Heiress Amassed a Huge Russian Art Collection (April 25, 2018). (Roy Tomlin shared both links.)

A Fabergé visit to the Houston Museum of Natural Science (HMNS) in Texas begins on the second floor of the museum as one enters the Cullen Hall of Gems and Minerals displaying over 750 gem and mineral specimens in their natural state. Dazzling colors of tourmaline crystals, massive quartz specimens and precious, colorful fluorites, beryls and corundums are a paradise for geologists and students of mineralogy. Photographer Ed Uthman has captured their beauty with specimen close-ups starting at slide # four. Next it will be hard to decide, if you should turn into the re-designed Lester and Sue Smith Gem Vault where cut, faceted and polished jewels beckon to the gem collector and/or the admirer of jewelry. Fabergé enthusiasts will immediately be drawn to an elegant entrance for the well-known McFerrin Collection of Fabergé and Russian art objects consisting of more than 600 objects now installed in a permanent gallery.

Two previous temporary exhibitions, each connected with well-attended Fabergé symposiums in 2013, (Fabergé Research Newsletter, Winter 2012-2013), a video of the Fabergé: A Brilliant Vision venue narrated by Timothy Adams and Tatiana Fabergé, and a symposium in 2016 (Fabergé Research Newsletter, Winter 2016) tell the story. The beautiful Dorothy and Artie McFerrin Gallery was dedicated in the spring of 2017 to the joy and delight of the honorees, family, friends, and museum supporters. Sadly, Artie McFerrin passed away in August 2017. He leaves a wonderful legacy in the McFerrin Collection at the museum as he did in so many ways for his alma mater, Texas A&M University in College Station, and other philanthropies. The gallery’s opening exhibition, Fabergé: Royal Gifts, included a one-year loan which ended Easter 2018 of a jeweled automaton elephant. The story of the elephant’s discovery and its connection to the McFerrin’s 1892 Diamond Trellis Egg by Fabergé is best viewed in this video conversation between HMNS President Joel Bartsch and Caroline de Guitaut, Curator of Decorative Arts, Royal Collection in London.

If you are lucky enough to be in the McFerrin Gallery on certain days a unique learning experience is in store for you. Two members of the HMNS Rock Stars Demonstration Team agreed to tell their story about a special gift from Dorothy and Artie McFerrin to the museum’s Fabergé volunteers.

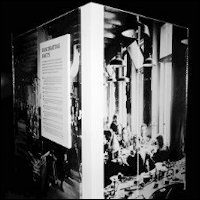

Hidden Rock Star Studio

with Fascinating Facts and

Fabergé Workshop Photographs

Zainab “Zee” R. Naqvi Demonstrating

Lapidary Techniques to Visitors

Cabbing and Faceting Machines

(Photographs by Jill Rowlands Moffitt)

While the masterfully-created elephant automaton from the Royal Collection was on loan for a year and fortunately displayed close to the hidden studio, the docents enjoyed pointing him out to interested visitors as a merger of carving and faceting, along with mechanical and jewelry techniques. The informative video near the Diamond Trellis Egg outside of the hidden room helps visitors and docents admire the elephant surprise now back in London. During your visit to the museum, look for the Rock Stars in the hidden studio which has a closet with shelves for equipment and materials, plenty of electrical outlets, special lighting as well as a cozy workbench and stools. If you hear an unusual grinding sound in the Fabergé gallery, search for the Rock Stars! We love doing demos and sharing our knowledge. We thank the McFerrin’s and our other donors many times over!

On July 27, 2018, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (VMFA) in Richmond is hosting a Fabergé enthusiasts gathering. A highlight will be the unveiling of the new book, Fabergé: His Masters and Artisans by Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm, who has studied Faberge Finnish workmasters since the 1980’s.

The 1903 Peter the Great Egg was shown at the Park Avenue Armory Winter Antiques Show in New York in January 2018. (VMFA, Winter/Spring 2018, p. 11)

Tillander-Godenhielm, Ulla. Faberge:

His Masters and Artisans, 2018

Miniature of Falconet Statue

of Peter the Great in the 1903

Peter the Great Egg

(Virginia Museum of Fine Arts,

Bequest of Lillian Pratt,

Photo: Katherine Wetzel

© Virginia Museum of Fine Arts)

The search tool offers an intuitive desktop and mobile experience, allowing users to browse via collection area, artist, geographic location, genre, and more. Each object entry provides detailed information and images of the work, and automatically links to related audio and video files, archival materials, and rare books, as well as to relevant resources available on the Learn Portal, which is VMFA’s other new site for all of the museum’s digital education initiatives. For example, the entry for Fabergé’s Imperial Peter the Great Easter Egg not only provides complete information about the object in 18 different fields of data, but also 60 images of the egg, as well as links to the original invoices for the egg, annotations by Lillian Thomas Pratt, and copies of the books Hammer Galleries created to illustrate her growing collection.

New acquisitions are added to the site shortly after being entered into the museum’s collections management system, and the dynamic site is constantly updated with new content and updated object information. The project is part of a three-year initiative, which incorporates on-site, web-based, and statewide education components, and is made possible through a $1 million grant awarded to the museum by the Lettie Pate Evans Foundation in 2016. Additional information: Press release.

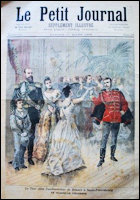

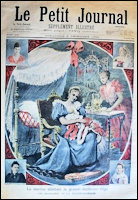

Three unique issues of Le Petit Journal and a sealed deck of Romanov playing cards from the Piatnik History of Russia, both relating to Imperial Russia, were discovered during a warehouse move by auction catalog dealer, Jeffrey Eger. They were donated to the McCanless Fabergé Archives at the Freeman Library, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Virginia.

French Daily Newspaper Supplements, 1893, 1895, 1901

(McCanless Collection)

Piatnik Romanov Playing Cards

(Wiki)

Contemporary View of Marie Feodorovna

Courtesy of Will Lowes who writes: “Today in May 2018 came across this report from the Adelaide Evening Journal (Australia), Saturday, May 8, 1909 — it was true then, as it remains true today…”)

No other royal lady in Europe has more claim to the title “A Queen of Tears” than the Dowager-Empress of Russia, and the brightest moments of her life are during her yearly visits to England as the guest of her sister, Queen Alexandra. She was little more than a child when she became betrothed to the then Tsarevitch, but before the marriage could take place her fiancé was stricken down with a mortal illness. He summoned the Princess and his younger brother to his bedside. “Marry her,” he said to his brother, joining their hands. “It is my dying request: And you, my dearest, you will be Empress of Russia all the same. Your destiny will be accomplished.” A few years after this marriage had taken place her father-in-law, the Emperor Alexander II, was blown almost to pieces in the streets of St. Petersburg. This horrible tragedy brought home to her the daily, almost hourly, danger in which she and her husband lived.

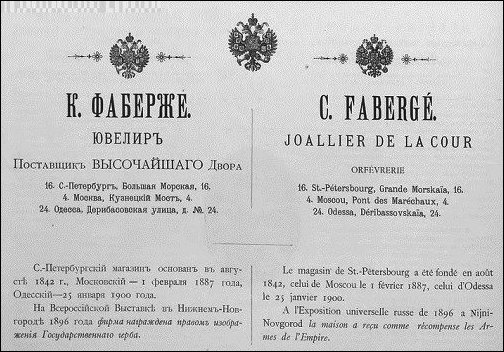

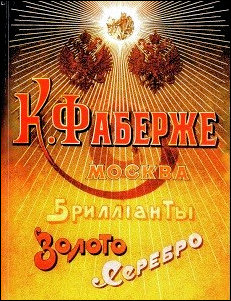

Fabergé Advertisements

Advertisement, 1900 Paris

World Exhibition Catalog

(Courtesy Natalia N. Sapfirova)

Moscow Price List 1899 with 69 Pages,

1902 Reduced to 14 Pages

(McCanless Collection)

A newsletter reader asked about the spelling deviation on the first name of Karl Gustavovich Faberge (1846-1920), i.e., in Russian – K. FABERGÉ, in French – C. FABERGÉ. This difference can be simply explained, in French the name is written as Charles. Consequently, the Latin initial “C” is used. French was a second language used in aristocratic society, and businesses proudly accented the dignity of their goods or services with references to their Parisian origin – “goods from Paris”, “a master from Paris”, etc.

Another reader asked about the Nizhny Novgorod Fair on the advertisement. Skurlov responded: The right to depict the State Emblem of Fabergé was received in 1885, and a second time in 1896 as the highest award at the Nizhny Novgorod Exhibition of 1896. After that the sale of jewelry by C. Fabergé was allowed 40 days per year in room number 26, a location within the Nizhny Novgorod Fair Grounds.

The newspaper, Illustrated Russia, published during the 1924-1929 Russian emigration and beyond to Paris contains an advertisement by the successors of the C. Fabergé firm. It ran from 1927 to 1935 with this information – Fabergé & Co. located on rue Saunier 23, performing orders, engaged in buying and selling, as well as receiving diamonds, pearls, precious stones. In 1935, the announcement was supplemented by the fact that the firm buys the products of the firm K. Fabergé.

Facsimile editions of Moscow branch promotional catalogs with price lists were reprinted in limited editions by Tatiana Faberge and Valentin Skurlov for the year 1893 (51 pages), 1899 (69 pg., 7 x 9 1/4 in., illustrated above), and 1902 (14 pg., size reduced to 4 x 6 in.) After the first and last exhibition in 1902 of Fabergé’s objects in the von Dervis Mansion in St. Petersburg, the Faberge firm stopped issuing new price lists and reduced the number of advertisements in print media. Why? After the World Exhibition in Paris in 1900 the firm received a large number of orders and was not able to produce them in time. The same year Faberge was asked by a journalist: “Probably, you received a lot of orders?” Fabergé answered, “Who will execute these orders? Where can I find the masters?” Another reason was the firm had switched to commission orders and no longer published design. The Price List of 1899 has an interesting note – “The firm does not publish its best projects in order to avoid falsification.” Copyright protection in Russia and in other countries was just beginning to form. Franz Birbaum in his memoirs1 notes other firms – Suppliers of the Highest Court – filled commission work without bearing the cost of maintaining the studio artists, performed these projects cheaper, and won the orders of His Majesty’s Cabinet.

1von Habsburg, Géza, and Marina Lopato. Fabergé: Imperial Jeweler, 1993, pp. 444-461.

Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm, author of Fabergé, His Masters and Artisans (published in May 2018) shares her latest research on the lives of the workmasters and artisans who worked for the Fabergé firm. She advises: “Neither Gabriel Nykänen nor journeyman Goldsmith (Karl) Gustav Lundell ever worked in the Odessa shop. A younger member of the Nykänen family, Frans Botolf Nykänen, a nephew of Gabriel, is known to have worked in Fabergé’s Odessa workshop from 1902 onwards, but not as the head of it.”

Fabergé Flowers:

Barberry Bush Sprig

& Morning Glory

(Courtesy Hansons’ London)

Pear Blossom

(Evening Standard, March 30, 2018)

“Fabergé: 7 Things You Need to Know” by Christian House, Sotheby’s (May 23, 2018)

Steve Kirsch, whose theory is – “Every Fabergé acquisition has a story attached to it, some more interesting than others” – shared two fascinating examples:

Bonbonnière by Mikhail Perkhin

(Courtesy Sotheby’s)

Fabergé Stock # 9749

Wartski Advertisement

in Connoisseur

(American Edition),

May 1959: Ad page 33

Faberge Demi-lune Box

(Courtesy Sotheby’s)

Wartski Advertisement

from the Connoisseur

Year Book, 1955:

Ad page 19

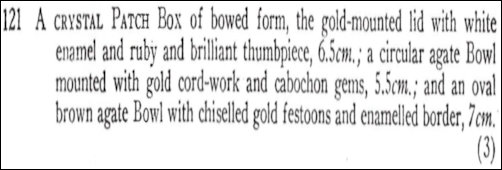

The Palace Collections Egypt (Farouk Auction)

Sotheby and Co., March 10, 1954, Lot 121, First Object (McCanless Collection)

The documentation is now united with the objects!

1The term “patch box” should not be applied to very small Fabergé boxes. Historically, patches went out of fashion with Madame de Pompadour (1721-1764).

Dr. Adam Szymanski, Polish art historian specializing in Russian art and Fabergé, has found Kelkh tableware. Provenance details and documentary evidence, if the Alexander and Barbara Kelkh set was melted down, have not yet been found. Additional information: Royal Russia News, September 15, 2017.

Readers Asking for Assistance!

1897 Coronation Egg

(Courtesy Fabergé Museum,

St. Petersburg, Russia)

Sir William Seeds Collection, Exhibited in London, 1973

(Courtesy Wartski)

- June 8, 1935. Sold to Arthur E. Bradshaw, London, for £1,900

- 1939. Sold back to Wartski after Bradshaw’s death

Bradhaw also was the proud owner of the von Bolfras Imperial presentation snuff box (previously known as the “Coronation Box, discussed in detail in the Features section of this newsletter) and the ten Faberge hardstone figures later owned by Sir William Seeds. Ms. Allen is interested in learning where other Fabergé objects, once owned by her ancestor, are located. Contact: Jane Allen

Horst Becker in Wiesbaden (Germany) is asking for assistance in planning a Fabergé exhibition to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Carl Fabergé’s death in 1920. An article by Becker entitled, “Ostereier von Weltruf” (Easter Eggs of World Renown) was published in the lilienjournal: Wiesbadener Stadtansichten, Spring 2018, pp. 24-25. In German.