(A.)

(B.)

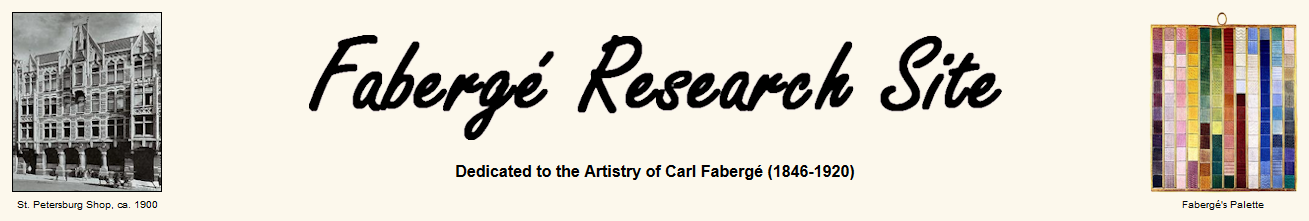

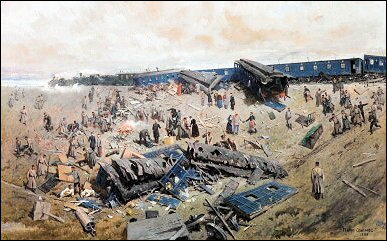

Borki Train Disaster with Two Damaged Steam Engines, Dining Car and Grand-ducal Wagon by Aleksei Ivanitskii (1854-1920) (UPPER RIGHT PICTURE: Alexei Ivanitskii, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons; BOTTOM PICTURE: Krog, Ole Villumsen, Ulstrup, Preben, et al., Treasures of Russia – Imperial Gifts, 2002, No. 13, p. 238)

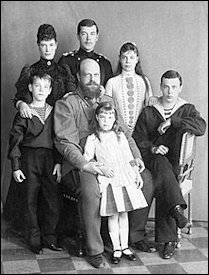

(B.) Russian Imperial Family (Outer Circle, Left to Right): Empress Maria Feodorovna, Future Emperor Nicholas II, Grand Duchess Ksenia, and Grand Duke Georgii (Inner Circle): Emperor Alexander III with Grand Duke Mikhail (Left) and Grand Duchess Olga (Right), Photograph, ca. 1889. (Courtesy Royal Collection)

Chamber Cossack Tikhon Egorovich Sidorov, Empress Maria Feodorovna’s Personal Bodyguard, Lost His Life (Charles Bergamasco, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Crumpled Gilded Traveling Inkwell with Empress Maria Feodorovna’s Monogram by Russian Silversmiths Nicholls & Plincke (Krog, Ole Villumsen, Ulstrup, Preben, et al., Treasures of Russia – Imperial Gifts, 2002, No. 13, pp. 236-2412)

Miraculously, the entire Imperial Family survived. The Empress cared for the wounded while the Emperor helped to retrieve the dead in the cold rain and harsh winds until additional help arrived from Kharkov. Most of the surviving passengers suffered small cuts and bruises from broken glass and flying debris. The Empress injured her left hand, and the Emperor sustained a significant soft tissue injury to his right leg caused by the crushing of a silver cigarette case in his pocket. Professor Wilhelm Grube, Director of the Kharkov University Clinical Department, examined Alexander III and recorded blunt trauma in the kidney region.4 In a November 6, 1888 letter, the Empress explained to her brother, King George I of the Hellenes (1845-1913), her injured left hand was ‘completely black’ and Alexander III’s leg was ‘completely black from the hip to the knee.’5 The Emperor’s subsequent nephritis and death six years later at age 49 were often attributed to the injuries he sustained in the accident.

(C.) Medal Commemorating the Borki Accident by Abraham Griliches (1849-1912)

(Courtesy Royal Collection)

(B.1) Russian Imperial Family

(Outer Circle, Left to Right):

Empress Maria Feodorovna (1847-1928),

Future Emperor Nicholas II (1868-1918),

Grand Duchess Ksenia (1875-1960),

and Grand Duke Georgii (1871-1899).

Inner Circle: Emperor Alexander III

(1845-1894) with Grand Duke Mikhail

(left, 1878-1918) and Grand Duchess Olga

(right, 1882-1960), Photograph, ca. 1889.

(Courtesy Royal Collection)

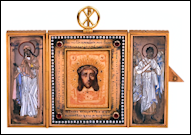

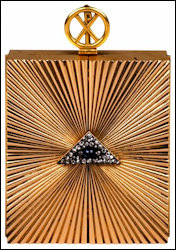

(D.) Emperor Alexander III

(1845-1894), Commemorative Travelling

Triptych (Christie’s New York,

October 27, 1987, Lot 93)

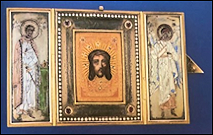

(E.) Empress Maria Feodorovna

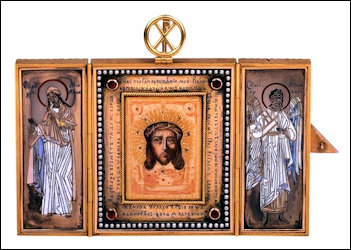

(1847-1928) Triptych Icon (Krog,

Ole Villumsen, Ulstrup, Preben, et al.,

Treasures of Russia – Imperial

Gifts, 2002, No. 15, pp. 242-245;

Uppsala Auktionskammare,

Sweden, June 2, 2006, Lot 1162)

(Also described in the literature as a medal, pendant, jeton, or icon)

(F.) Grand Duchess Ksenia

Aleksandrovna (1875-1960),

Commemorative Pendant,

Russian Inscription on Photograph,

In Memory of [Our] Salvation 17

October 1888

(Date Omitted in Christie’s New

York, May 20, 2015, Lot 21)

(G.) Grand Duke Georgii

Aleksandrovich

(1871-1899) Medallion

Discovered in His Tomb

in 1994.

(Courtesy Sergei Nikitin)

Borki medallions have not been

found for the future Emperor

Nicholas II, Grand Duke Mikhail,

and Grand Duchess Olga.

An attempt was made to locate

a Borki medallion in Nicholas II’s

jewel album.8 Neither a Borki

medallion nor any other religious

medallions were identified among

the entries for the years 1888

and 1889. One must consider

whether its absence is related to

how the future emperor, or the

individual(s) preparing the

album perceived this tiny object.9

Was it an oversight or was the

medallion not considered “jewelry”,

but rather a spiritual talisman

signifying God’s protection over

the Tsesarevich, and his siblings?

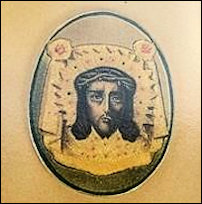

(H.) Countess Elena Grigorievna

Sheremeteva, neé Stroganova

(1861-1908) Medallion of the Vernicle10

(Christie’s Geneva, November 12,

1985, Lot 315; Commemorative Medal,

Christie’s New York, April 16, 1999,

Lot 85, descriptive data no longer

on the website.)

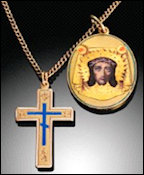

(I.) Dr. Gustav Ivanovich Hirsch

(1828-1907) Commemorative Pendant

(Christie’s New York, April 21, 1998, Lot 4

(no longer illustrated on the website);

Sotheby’s London, May 19, 2005,

Lot 202 with a Chain and Cross)

(J.) Major-General Baron Knut

Stjernvall (1819-1889) Jeton

(Tillander-Godenhielm, Ulla. Smycken

från det Kejserliga S:t Petersburg,

1996, pp. 135-139; Tillander-Godenhielm,

Ulla. “Brief Overview of the Russian

Imperial Award System” in The Era of

Fabergé, 2006, pp. 138-141, 163-164)

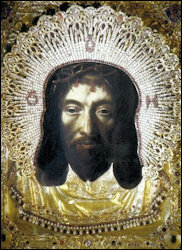

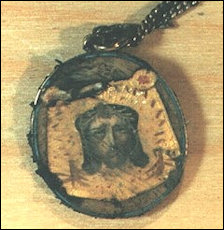

- Christ wears a crown of thorns, a late feature taken from Western images.

- In 1872, a sumptuous, jewel-studded, gold oklad (metal cover) was added to the original icon, which in later copies of the image is frequently simulated with paints or less valuable materials.13

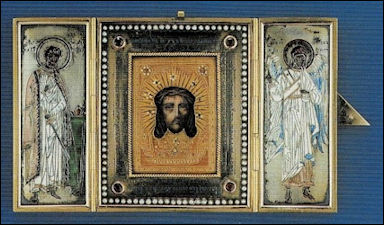

(K.) Central Frame of Maria Feodorovna’s

Fabergé Triptych with Romanov Savior

and Its Jeweled Oklad Simulated with

Multi-colored Enamels.

(Uppsala Auktionskammare, Sweden,

June 2, 2006, Lot 1162)

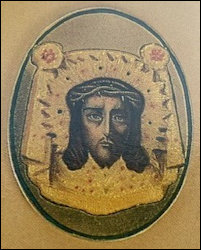

(L.) Romanov Savior Icon in a Gold Frame. By Tradition Belonged to Peter the Great (1682 -1725),

Now in the Spaso-Preobrazhensky Cathedral, St. Petersburg, Russia

(Photographs Courtesy Ilya Sovetin, Website Administrator of the Spaso-Preobrazhensky Cathedral)

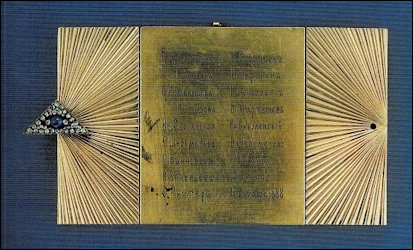

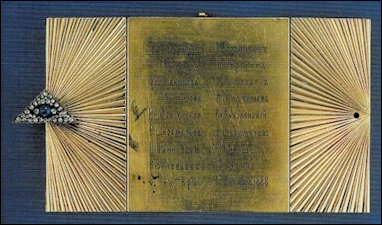

(D.1) 1987 Auction – First Look at the Donors List on the Verso of

the Traveling Triptych Presented to Emperor Alexander III.

(Christie’s New York, October 27, 1987, Lot 93)

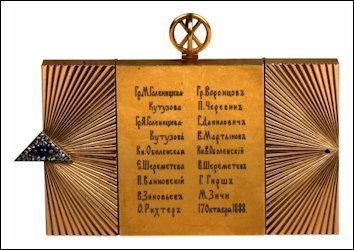

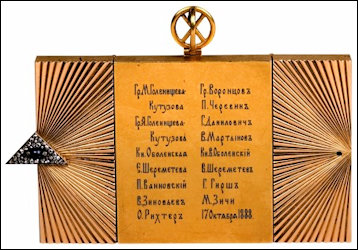

(E.1) 2006 Auction – Donors List on the Empress Maria Feodorovna

Fabergé Triptych Icon

(Uppsala Auktionskammare, Sweden, June 2, 2006, Lot 1162)

| Name with Birth-Death Dates | Positions at the Russian Imperial Court in 1888i | Verification of Passengers on the Train |

|---|---|---|

| Countess Maria Vasilievna Golenishcheva-Kutuzova (1851-1915)ii | Maid of Honor to the Empress Maria Feodorovna; Sister of Aglaida Vasilievna Golenishcheva-Kutuzova | Grand Duchess Olga Aleksandrovnaiii; Borki Accident Booklet 1888iv |

| Countess Aglaida Vasilievna Golenishcheva-Kutuzova (1853-1920)v | Maid of Honor to the Empress Maria Feodorovna; Sister of Maria Vasilievna Golenishcheva-Kutuzova | Letter to Queen Louise of Denmark from Empress Maria Feodorovnavi |

| Princess Aleksandra Aleksandrovna Obolenskaia, neé Countess Apraksina (1852-1943) | Former Maid of Honor to the Empress Maria Feodorovna; Wife of Count Vladimir Sergeevich Obolenskii | Aleksandra Viktorovna Bogdanovichvii |

| Countess Elena Grigorievna Sheremeteva, neé Countess Stroganovaviii (1861-1908) | Cousin of Emperor Alexander III; Granddaughter of Emperor Nicholas I; Wife of Vladimir Alekseevich Sheremetev | Borki Accident Booklet 1888 |

| Petr Semenovich Vannovskii (1822-1904) | Aide-de-Camp-General, General of the Infantry; Minister of War | Aleksandra Viktorovna Bogdanovich; Vasilii Silovich Krivenkoix |

| Vasilii Vasilievich Zinoviev (1814-1891) | Aide-de-Camp-General, General of the Infantry; Steward of His Majesty’s Own Palace, and the Affairs & Office of the Most August Children of Their Imperial Majesties | Aleksandra Viktorovna Bogdanovich; Vasilii Silovich Krivenko |

| Otton Borisovich Richter (1830-1908) | Aide-de-Camp-General, General of the Infantry; Commander of the Imperial Headquarters; Head of the Chancellery for Receipt of Petitions Submitted to His Imperial Majesty | Vasilii Silovich Krivenko; Borki Accident Booklet 1888 |

| Count Illarion Ivanovich Vorontsov-Dashkov (1837-1916) | Aide-de-Camp-General, Lieutenant-General; Minister of the Imperial Court and Appanages; Chancellor of the Imperial and Russian Orders | Vasilii Silovich Krivenko; Borki Accident Booklet 1888 |

| Petr Aleksandrovich Cherevin (1837-1896) | Aide-de-Camp-General, Lieutenant-General; Chief of Emperor Alexander III’s Security | Aleksandra Viktorovna Bogdanovich; Vasilii Silovich Krivenko |

| Grigorii Grigorievich Danilovich (1825-1906) | Aide-de-Camp-General; Tutor to Tsesarevich Nikolai Aleksandrovich and Grand Duke Georgii Aleksandrovich | Vasilii Silovich Krivenko |

| Valerian Dmitrievich Martynov (1841-1901) | Major-General; Master of the Horse in Active Service; Manager of the Court Stables | Herman Aleksandrovich Goldbergx; Borki Accident Booklet 1888 |

| Prince Vladimir Sergeevich Obolenskii (1847-1891) | Aide-de-Camp to the Emperor; Marshall of the Imperial Court; Colonel of Her Majesty Empress Maria Feodorovna’s Chevaliers Guards Regiment | Aleksandra Viktorovna Bogdanovich; Vasilii Silovich Krivenko |

| Vladimir Alexeevich Sheremetev (1847-1893) | Aide-de-Camp to the Emperor, Colonel; Commander of His Imperial Majesty’s Own Konvoi | Aleksandra Viktorovna Bogdanovich |

| Gustav Ivanovich Hirschviii (1828-1907) | Life-Surgeon to His Imperial Majesty; Personal Physician to Emperor Alexander III | Vasilii Silovich Krivenko; Borki Accident Booklet 1888 |

| Mihály Zichy (1827-1906) | Hungarian Artist; Imperial Court Painter | Vasilii Silovich Krivenko |

i Daniel Brière shared his vast knowledge for the structure of the ‘Suite of His Imperial Majesty’. The members’ titles of the Emperor’s Suite were Aide-de-Camp to the Emperor (Fligel-Adjutant) for officers below the rank of Major-General, Major-General of the Suite of His Majesty (Генерал-майор свиты Его Величества) and Aide-de-Camp-General (General-Adjutant) for Lieutenant-Generals and Generals. It is noted there were also Major-Generals in the presence of the Emperor, who were not members of the Suite, i.e., in the case of Major-General Valerian Dmitrievich Martynov in 1888.

ii Personal correspondence: Galina Korneva, Imperial Russian History Researcher, shared biographical information on Countess Maria Vasilievna Golenishcheva-Kutuzova and her injury on the train (Art Revue Magazine, 1888, #45, p. 302). 9/27/21.

iii Kulikovsky, Paul, Woolmans, Sue, and Karen Roth-Nicholls (eds.). 25 Chapters of My Life: The Memoirs of Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna, 2014, p. 24.

iv Booklet (Author Unknown). “Чудо милости Божией. Дивное спасение государя императора Александра Александровича, супруги его государыни императрицы Марии Федоровны и августейших детей их” (The Miracle of God’s Mercy: The Miraculous Salvation of the Emperor Aleksander Aleksandrovich, His Wife Empress Maria Feodorovna, and Their August Children). Moscow, Publishing House of I.D. Sytin and Company, 1888. Compiled according to telegrams from the Minister of the Imperial Court and other official data published in the Government Bulletin, Russian Invalid, Moskovskie Vedomosti and Moskovsky Listka. The booklet contains detailed descriptions of the accident, its aftermath, and the Imperial Family’s journey back home to Gatchina, and Court Painter Mihály Zichy’s sketch of the train’s dining room seating chart (H.2) on the day of the accident (p. 7), and his recollections of the event.

v Personal correspondence: Galina Korneva, Imperial Russian History Researcher, shared biographical information on Countess Aglaida Vasilievna Golenishcheva-Kutuzova, who was injured in the Borki train accident, died at sea on March 30, 1920, while being evacuated from Russia, and is buried on the Greek Island of Lemnos. 5/22/22.

vi Krog Ole Villumsen, Ulstrup, Preben, et al., Treasures of Russia – Imperial Gifts, 2002, No. 13, pp. 236-241. Contains Empress Maria Feodorovna’s letter to her mother, Queen Louise of Denmark.

vii Богданович, Александра Викторовна. Дневники 1879-1912 (Bogdanovich, Alexandra Viktorovna. Diaries 1879-1912), 2018, pp. 66-72.

viii Also received a Borki Medallion (H. and J.)

ix Кривенко, В.С. Очерки Кавказа Том I: Поездка на Кавказь Осенью 1888 года (Krivenko, V.C., Essays on the Caucasus Volume 1: A Trip to the Caucasus in the Autumn of 1888), 1893, p. 240.

x Гольдберг, Герман Александрович, ред. Альманах современных русских государственных деятелей (Goldberg, Herman Aleksandrovich, ed. Almanac of Modern Russian Statesmen), St. Petersburg, 1897, p. 304.

Two individual triptych donors, Countess Elena Sheremeteva (H.1), and Dr. Gustav Ivanovich Hirsch (I.1), also received a Borki medallion from the Emperor and his consort. These comprehensive facts enhance our knowledge of the seven Borki Fabergé objects which have survived the ravages of time for 134 years:

-

Two Borki Fabergé triptych icons and one medallion are stamped with Fabergé’s chief workmaster Erik Kollin’s mark (

active 1870-1901).

active 1870-1901).

- Four Borki medallions are not marked or cannot be identified. Despite these issues, the medallions were almost certainly made by Erik Kollin when their designs, craftsmanship, materials, sizes, and most importantly, central theme are studied in more detail.

Each folding triptych shares a similar design – A divided gold frame for three images struck with Kollin’s mark ![]() , the pre-1899 St. Petersburg assay hallmark

, the pre-1899 St. Petersburg assay hallmark ![]() denoting the 56 zolotniks gold standard (14K-583), and the city’s coat of arms. Alexander III’s icon fully opened measures 9.5 cm, while Maria Feodorovna’s triptych icon at 10.5 cm is slightly larger. The interior’s central feature is an enameled Romanov Savior bordered by gold ropework in Kollin’s signature ‘archeological-revival’ style. The outer border of the central frame contains Cyrillic prayers encased by seed pearls and ruby accented corners. One wing of each triptych (left side in illustration D.2-E.2) contains the corresponding champlevé enameled patron saint of the Emperor and Empress: St. Alexander Nevsky and St. Mary Magdalene. The other wing (right side in illustration D.2-E.2) houses a champlevé enameled guardian angel. The wings’ exteriors are molded into a sunburst pattern surmounted by a rose-cut diamond and cabochon sapphire All Seeing Eye of God clasp. The design was an ideal motif for conveying God’s protection of the Imperial Family with the pyramid’s corners symbolizing the Holy Trinity, the Eye representing God’s omniscience, and the golden sunrays denoting holiness. The back of each triptych is inscribed with the names of 15 donors and the date of the railway accident in blue enamel (D.1-E.1). Many of those named on the icons are known to have had close relationships with the Imperial couple. Prior to the accident, several of the donors lived in close proximity to Alexander III and his family within Gatchina Palace: Count Vorontsov-Dashkov, the Sheremetevs, the Obolenskiis, and the Golenishcheva-Kutuzova sisters.21 It is interesting to note the names of nobility include abbreviated forms of their titles except for Countess Elena Sheremeteva22. She was a Stroganov countess by birth, but her husband descended from of a non-titled branch of the Sheremetev family23, so perhaps her title was omitted due to their unequal marriage. My search of archival documents and diary entries, memoirs, historical essays, and other sources provided evidence that all donors listed on the triptychs were onboard the Imperial train during the accident.

denoting the 56 zolotniks gold standard (14K-583), and the city’s coat of arms. Alexander III’s icon fully opened measures 9.5 cm, while Maria Feodorovna’s triptych icon at 10.5 cm is slightly larger. The interior’s central feature is an enameled Romanov Savior bordered by gold ropework in Kollin’s signature ‘archeological-revival’ style. The outer border of the central frame contains Cyrillic prayers encased by seed pearls and ruby accented corners. One wing of each triptych (left side in illustration D.2-E.2) contains the corresponding champlevé enameled patron saint of the Emperor and Empress: St. Alexander Nevsky and St. Mary Magdalene. The other wing (right side in illustration D.2-E.2) houses a champlevé enameled guardian angel. The wings’ exteriors are molded into a sunburst pattern surmounted by a rose-cut diamond and cabochon sapphire All Seeing Eye of God clasp. The design was an ideal motif for conveying God’s protection of the Imperial Family with the pyramid’s corners symbolizing the Holy Trinity, the Eye representing God’s omniscience, and the golden sunrays denoting holiness. The back of each triptych is inscribed with the names of 15 donors and the date of the railway accident in blue enamel (D.1-E.1). Many of those named on the icons are known to have had close relationships with the Imperial couple. Prior to the accident, several of the donors lived in close proximity to Alexander III and his family within Gatchina Palace: Count Vorontsov-Dashkov, the Sheremetevs, the Obolenskiis, and the Golenishcheva-Kutuzova sisters.21 It is interesting to note the names of nobility include abbreviated forms of their titles except for Countess Elena Sheremeteva22. She was a Stroganov countess by birth, but her husband descended from of a non-titled branch of the Sheremetev family23, so perhaps her title was omitted due to their unequal marriage. My search of archival documents and diary entries, memoirs, historical essays, and other sources provided evidence that all donors listed on the triptychs were onboard the Imperial train during the accident.

(D.2) Emperor Alexander III

Portrait by Sergei Lvovich

Levitskii, ca. 1890

(Sergey Lvovich Levitskii,

Public domain,

via Wikimedia Commons)

Emperor Alexander III (1845-1894) Traveling Triptych, ![]() Mark on the Interior of the Central Panel,

Mark on the Interior of the Central Panel,

1888, Suspension Ring Missing, Open 3 1/4 in., 9.5 cm. First Look in 1987 at the Donors List on the Verso of the Triptych

(Christie’s New York, October 27, 1987, Lot 93, Price Realized $33,000)

(E 2.) Empress Maria Feodorovna Portrait

by Sergei Lvovich Levitskii, ca. 1892.

(Courtesy Royal Collection)

Empress Maria Feodorovna (1847-1928), Fabergé Triptych Icon,

(Krog, Ole Villumsen, Ulstrup, Preben, et al., Treasures of

Russia – Imperial Gifts, 2002, No. 15, pp. 242-245; Uppsala

Auktionskammare, Sweden, June 2, 2006, Lot 1162)

Closed Icon with the All Seeing Eye of God Clasp and Christogram Suspension Ring of Interlaced Greek letters Chi (Χ) and Rho (P),

Pre-1899 St. Petersburg Assay Mark, ![]() Mark, and Verso with 15 Donor Names and Accident Date.

Mark, and Verso with 15 Donor Names and Accident Date.

Provenance: By inheritance to her daughter, Grand Duchess Ksenia (1875-1960), then to her son, Prince Andrei Romanoff (1897-1981), thence by descent to his daughter,

Princess Olga Romanoff (1950- ). (Uppsala Auktionskammare, Sweden, June 2, 2006, Lot 1162, SEK 6,000,000, website highlights 11 photographs.)

Analysis: The assumption about the presentation date of this triptych – six days after the accident – is probably not correct for two reasons: How could the Fabergé studio finish such an elaborate triptych icon for the Empress, and a second nearly identical version for Emperor Alexander III, in just six days (October 17-23) after the accident? Since the evidence confirms all the donors were traveling on the train, the time needed to complete an elaborate commissioned triptych was far too short, especially, if the order was not placed until the imperial entourage reached Moscow (October 20, 1888), where Fabergé’s second branch specializing in silver was located. Incidentally, the list of donors includes both ladies and gentlemen, not strictly ladies as expressed by the Empress. Unfortunately, no year is given for her diary entry, but presumably it is 1888.

Front and Verso Illustration of Borki Medallions with Engraved Imperial Cyphers and the Memorial Text

(Christie’s New York, May 20, 2015, Lot 21, $27,500)

- Grand Duchess Ksenia’s medallion (F.1) lacks the Imperial Cyphers in the lot description, but they are shown in the accompanying photograph.

- Medallions for Grand Duke Georgii Aleksandrovich (G.1), Countess Elena Sheremeteva (H.1), and Major-General Baron Knut Stjernvall (J.1) have no known photographic records of their versos.

- Elena Sheremeteva’s medallion (H.1) was at auction twice with different translations of the memorial text.

A table of each of the five extant Borki medallions presents the details as they have been published:

| Name of Recipient | Fabergé and/or Workmaster Mark | Front: Romanov Savior in Blue Enameled Border | Verso: Memorial Inscription in Cyrillic | Verso: Translated Memorial Inscription in the Literature | Verso: Imperial Cyphers in Blue Enameled Border | Engraved Recipient’s Name on Edge | Suspension Ring & Loop | Shape & Size | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grand Duchess Ksenia Aleksandrovna (F.) | Probably by Fabergé; Indistinct Mark on Loop | Present | В память о спасения 17 Остября 1888 (on Photograph) | In Memory of [Our] Salvationi (Date Not Noted in Auction Catalog) | Present | Dear Ksenia: In Russian | Present | Oval, 1 1/2 in. (3.8 cm) | CNY, May 20, 2015, Lot 21, $27,500 |

| Grand Duke Georgii Aleksandrovich (G.) | Unknown | Present | No Verso Photograph; Nikitin’s Notes: В память о спасении. Борки. 1888 r. | None In Memory of Our Salvation. Borki. The Year 1888 (English Translation by Roy Tomlin) | Unknown | Unknown | Present | Oval, Exact Size Unknown | Natalya Rozanova (Footnote 25) |

| Countess Elena Sheremeteva (H.) | (1985) None; Probably on Missing Suspension Ring or Loop | Present | (1985) No Photograph nor Published Cyrillic Inscription | (1985) In Memory of the Miraculous Escape of 17 October 1888 | Present; Described in Catalog Only | No Details in Auction Catalog, States Presented to the Countess | Absent | (1985) Oval, 3.5 cm: Height Variance Due to Absent Suspension & Loop | CG, Nov 12, 1985, Lot 315, SFr 6050 |

| (1999) By Fabergé, Probably by Workmaster Erik Kollin; Apparently Unmarkedii | Present | (1999) No Photograph nor Published Cyrillic Inscription | (1999) In Memory of Our Escape (No Date Noted in Catalog) | Present; Described in Catalog Only | E. G. Sheremet’ev: In Russian | Absent | (1999) Oval, 1 3/8 in. (3.5 cm): Height Variance Due to Absent Suspension Ring & Loop | CNY, 16 April 1999, Lot 85, Did Not Sell |

|

| Dr. Gustav Ivanovich Hirsch (I.) | (1998) Fabergé, | Present | (1998) В память о спасения 17 Остября 1888 | (1998) In Memory of Our Escape 17 October 1888 | Present | G.I. Hirsch: In Russian | Present; Marked on Ring | (1998) Oval, 1 1/2 in. (3.8 cm)iii | CNY, April 21, 1998, Lot 4, $17,250 |

| (2005) Fabergé, Erik Kollin, Fabergé Workmaster | Present | (2005) В память о спасения 17 Остября 1888 | (2005) In Memory of Our Escape 17 October 1888 | Present | G.I. Hirsch: In Russian | Present; Marked on Ring | (2005) Oval, 1 1/2 in. (3.8 cm) | SL, May 19, 2005, Lot 202, £9,000 | |

| Major-General Baron Knut Stjernvall (J.) | Unknown | Present | No Photograph nor Descriptive Data Available (Private Collection) | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Present | Oval, Exact Size Unknown | Courtesy Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm |

i The Russian noun ‘спасение’ means salvation, rescue, or escape. The English translation of this word has led to a variety of inscription interpretations on the Borki medallions in the literature. Due to the grammatical declension of Russian nouns, the word ‘спасение’ appears as ‘спасения’ and ‘спасении’ in the inscriptions.

ii The auction catalog states this medallion is ‘apparently unmarked’, but was likely marked on the missing suspension ring or loop.

iii As of 6/5/22, there is a discrepancy between the printed 1998 Christie’s catalog and the Christie’ website relating to Hirsch’s Borki Medallion. The printed catalog correctly has the size as 1 1/2 in. (3.8 cm), but the website currently has it incorrectly cited as 1 in. (3.8 cm).

An intact mark by Erik Kollin ![]() was found only on one medallion (I.1) given to Dr. Gustav Ivanovich Hirsch (1828-1907), the Emperor’s personal physician. The text states it is marked on the suspension ring, but not illustrated. The other medallions closely mirror the confirmed Fabergé example, so perhaps no other Fabergé workmasters were involved.

was found only on one medallion (I.1) given to Dr. Gustav Ivanovich Hirsch (1828-1907), the Emperor’s personal physician. The text states it is marked on the suspension ring, but not illustrated. The other medallions closely mirror the confirmed Fabergé example, so perhaps no other Fabergé workmasters were involved.

One is missing its suspension ring and loop where it was most likely marked (H.1)

Marks on two are unknown (G.1 and J.1)

One shows illegible marks (F.1) The medallion with the illegible marks may be partly explained, if it had been worn on a chain causing erosion over time of the marks on the suspension ring or loop.

Ksenia Aleksandrovna’s medallion matches on both sides the known Fabergé example given to the Emperor’s personal physician, Dr. Gustav Ivanovich Hirsch (I.1). The 13-year-old Grand Duchess was seated in the dining car at the time of the accident. Her medallion was taken into exile by the Grand Duchess when she fled Russia in 1919, and remained within her family until it was sold in 2015.

CLICK THE ABOVE RIGHT PICTURE FOR A LARGER VIEW

(F.1) Grand Duchess Ksenia Aleksandrovna Romanova (1875-1960)

Portrait by Sergei Lvovich Levitskii, ca. 1888

(Sergey Lvovich Levitskii, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Borki Medallion, Front, Verso with Engraved Dedication (“Dear Ksenia”) on the Edge. Described by

the auction house as “probably by Fabergé.” Indistinct marks on loop. Height: 1 1/2 in. (3.8 cm)

with suspension ring and loop.

(Christie’s New York, May 20, 2015, Lot 21, $27,500)

Provenance: By inheritance to Prince Nikita Alexandrovich (1900-1974); Prince Alexander Nikitich (1929-2002).

(G.1) Grand Duke Georgii Aleksandrovich Romanov (1871-1899)

(Hermitage Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Borki Medallion Found in 1994, Tomb of Grand Duke Georgii Aleksandrovich. Medallion’s Inscription: В память о спасении. Борки. 1888 г.

(In Memory of [Our] Salvation. Borki. The Year 1888)

Marks: Unknown. Height: Unknown, but suspension ring and loop are present.

(Courtesy Sergei Nikitin)

My contact with Dr. Sergei Nikitin, Chief Specialist of the Moscow Bureau of Forensic-Medical Examination, who was present at the Grand Duke’s exhumation, was facilitated by Captain Peter Sarandinaki, President of SEARCH Foundation, Inc. Nikitin shared a larger photograph of the Borki medallion with a silver medal on the gold chain found in the tomb as described in Rozanova’s book. Through correspondence with Ilya Korovin, Manager of the Ekaterinburg Complex of Royal Graves, acting as an intermediary, I contacted Vladimir Nikolaevich Solovyov, former Senior Criminal Investigator of the Main Forensics Directorate of the Russian Investigative Committee, also present at the exhumation. He corroborated the Borki medallion was made of gold and hung on a gold chain, and he advised the Grand Duke had several medals, including a gold one with a lock of hair.26

Chief Specialist Nikitin did not possess nor did Rozanova’s book contain a verso photograph of Georgii Aleksandrovich’s Borki medallion, however, Nikitin had a description in his notes – the medallion’s inscription: В память о спасении. Борки. 1888 г. (In Memory of [Our] Salvation. Borki. The Year 1888).27 There is no mention of the Imperial Cyphers on the back of this medallion. The discrepancy in the verso design of the Grand Duke’s medallion from the others is a conundrum. The difference is puzzling since the front view is identical to all the other identified medallions. Regrettably, a larger sample size of Borki medallions was not available for comparison to ascertain, if there are variations in inscriptions and decoration on the verso of others presented by the Emperor and Empress. Despite this unexplained difference, this particular medallion was almost certainly created by Kollin for the Fabergé firm, given the cohesiveness of the frontal design, coloring, and execution. So perhaps, a small image of ‘Christ’ by Fabergé, a name so closely associated with the Russian Imperial Family, rests with the Grand Duke in his grave.

(H.1) Countess Elena Grigorievna

Sheremeteva, neé Stroganova

(1861-1908)

(Фотография, Public domain, via

Wikimedia Commons)

Borki Medallion, Edge of the medallion

is inscribed E.G. Sheremet’ev in Russian.

Marks: None present, most likely on the

missing suspension ring or loop.

Height: 3.5 cm

(Christie’s Geneva, November 12, 1985,

Lot 315, S Fr. 6050; Christie’s New

York, April 16, 1999, Lot 85, Not

Sold, Passed In, or Withdrawn.

Descriptive details no longer on

Christie’s New York auction website.)

Aide-de-Camp to the Emperor,

Colonel Vladimir Alekseevich Sheremetev

(1847-1893), Commander of His Imperial

Majesty’s Own Konvoi, the Emperor’s

Bodyguard

(Фотография, Public domain, via

Wikimedia Commons)

Analysis:

-

The first indication the Countess may have been on the train was my observation that Elena Sheremeteva’s name is listed on both Erik Kollin triptychs (D.-E.), and like Dr. Gustav Ivanovich Hirsch, Personal Physician to Emperor Alexander III (I.1), she received a Borki medallion from the Imperial couple.

-

The 1985 Christie’s Geneva auction catalog30 includes an English translation of the memorial text on the back of Sheremeteva’s medallion – In Memory of the Miraculous Escape of 17 October 1888. The second time this medallion was auctioned, the 1999 Christie’s New York catalog had a shortened inscription, In Memory of Our Escape and no mention was made of the accident date on the medallion’s verso. The description notes her name, ‘E.G. Sheremet’ev’ was engraved in Russian on the medallion’s edge. Unfortunately, no photograph of this medallion’s verso has been found. The memorial inscription including the accident date on the back of the medallion, as stated in the 1985 catalog, is very similar to the text on the medallions of Grand Duchess Ksenia Aleksandrovna (F.) and Dr. Hirsch (I.) If the actual inscription were available, a strong probability exists all three versos might share the same Russian text.

The 1985 catalog entry does not mention any connection to Fabergé, so were other medallions sold in the past without being associated with the famous court jeweler? This entry describes the object as a Medallion of the Vernicle and suggests “the Tsar had five medals made and presented to his ministers …” A literature reference in the auction catalog text cites G. Tchoulkov, Les Derniers Tsars Autocrates (Paris), [1928], p. 369.31 Upon review only the Borki accident specifics are briefly discussed in the French publication without any mention of commemorative objects. In 1999, the second time the medallion was under the hammer, it is described as Fabergé and probably by Kollin, and there is no further mention of the five medals presented to his ministers.

-

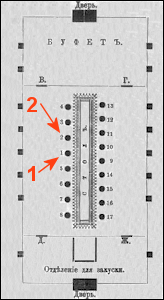

Two pieces of original art – a seating sketch32 and a watercolor painting – by the Imperial Court Painter Mihály Zichy (1827-1906), a passenger on the train, further supported Elena Sheremeteva was traveling with the Imperial Family and her husband. The seating sketch (H.2) of the Imperial train’s dining room on the day of the Borki accident has an added label – ‘Stats-Dama Sheremeteva’ – she is seated to the left of Emperor Alexander III. It was initially an enigma for me, since the Countess never held this title or any official positions at court other than being a friend and companion to the Empress. The official 1888 and 1889 Court Calendars list no ‘Stats-Dama Sheremeteva’ as a member of the Empress’ court staff.33 It appears, Zichy’s sketch is mislabeled with a court position the Countess never held, yet it strongly suggests Elena was on the train.

The Imperial Family and retinue stopped in Moscow to pray in the Kremlin’s churches and meet government officials when they made their return journey to St. Petersburg following the accident. A contemporaneous publication, compiled from official governmental information and approved news sources relating the events of the Borki accident and its immediate aftermath, states Countess Sheremeteva was seated to the right of Emperor Alexander III at a celebratory lunch in ‘Their Majesties’ Own Dining Room’ within the Great Kremlin Palace on October 20, 1888.34 It further notes the Countess was a Stroganov by birth, so Elena is the person being identified at the table.

(H.2) Seating Sketch, Imperial Train’s Dining Room on the Borki Accident Day. Seat #1 – The Sovereign (Emperor Alexander III),

Seat #2 – Stats-Dama Sheremeteva (Countess Elena Sheremeteva) by Mihály Zichy, Imperial Court Painter and Passenger on the 1888 Borki Train.

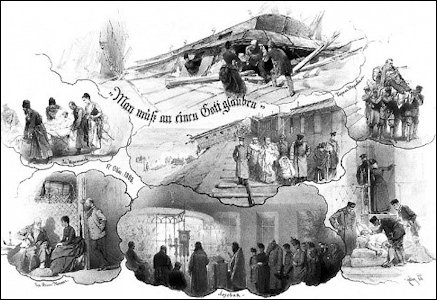

(Reference Source: Footnote 32)Black and White Photograph of a Watercolor Painting35 by Mihály Zichy, Imperial Court Painter

and Passenger on the 1888 Borki Train Wreck. German Quotation, “One Has to Believe in a God”.

(Зимин, И. Врач Двора Его Императоского Величества (Zimin, I. Doctors of the Court of His Imperial Majesty), 2016, p. 90) -

The Mihály Zichy watercolor painting (H.2) in the collection of St. Petersburg’s Russian Museum depicts a variety of vignettes from the railway calamity. A vignette (upper left) has the name V. A. Sheremetev [Aide-de-Camp to the Emperor, Colonel Vladimir Alekseevich Sheremetev] as a caption. The lady standing to the far right of the patient bears a striking resemblance to Elena Sheremeteva holding items from the Colonel’s uniform as she follows a group of Cossacks carrying him on a makeshift litter.

Aide-de-Camp General, Admiral Konstantin Nikolaevich Possiet (1820-1899) is pictured (lower left) with an injured left foot and visited by Emperor Alexander III and the Empress Maria Feodorovna. His medallion is not known at this time.

Another labeled vignette (upper right) depicts the injured Baron Major-General Baron Knut Adolf Ludvig Stjernvall (J.1), who was traveling on the train in his capacity as Chief Inspector of Russian Railways, being removed from the accident.

(I.1) Dr. Gustav Ivanovich Hirsch

[In Russian Гирш] (1828–1907)

(Unknown Author, Public Domain, via

Wikimedia Commons)

Borki Medallion with Chain,

Loop and Suspension Ring,

Erik Kollin

the Ring. Identified as

Fabergé, St. Petersburg.

Height: 1 1/2 in., 3.8 cm

(Christie’s New York,

April 21, 1998, Lot 4,

$17,250, no longer

illustrated on the website.)

Borki Medallion (left) with Chain, Loop, Suspension Ring,

and a Cross (not by Fabergé). Verso with Imperial

Cyphers and Memorial Text. Marks and Height same as the

1998 Christie’s auction.

(Sotheby’s London, May 19, 2005, Lot 202, £9,000)

(J.1) Major-General Baron Knut

Adolf Ludvig Stjernvall (1819-1899),

Engineer Active in the Development of

the Finnish and Russian Railways

Systems, Passenger on the Train

(Tillander-Godenhielm, Ulla. “Brief

Overview of the Russian Imperial

Award System” in The Era of Fabergé,

2006, pp. 138-141, 163-164)

Borki Medallion,

Marks and Height: Unknown.

(Tillander-Godenhielm, Ulla. Smycken

från det Kejserliga S:t Petersburg,

1996, pp. 135-139; Tillander-Godenhielm,

Ulla. “Brief Overview of the Russian

Imperial Award System” in The Era of

Fabergé, 2006, pp. 138-141, 163-164)

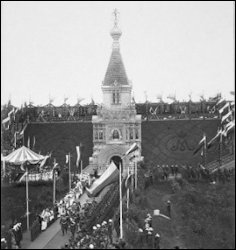

On June 14, 1894, a few months before his death, Emperor Alexander III, the Empress, and many members of the Romanov family returned to Borki for the consecration of the Cathedral of Christ the Savior built in memory of the accident.38 It assuredly brought up memories of the tragedy which nearly took their lives. The train’s derailment was a traumatic event for the Imperial Family, and especially for the youngest children. Grand Duchess Olga Aleksandrovna (1882-1960) admitted in her memoirs she dreamed of the catastrophe for years afterwards and often awakened during the night covered in sweat.39 She confessed she was still apprehensive when traveling by train.

(K.) View of the Cathedral of Christ the Savior and Chapel at Borki

(Aleksei Ivanitskii, Wikimedia Commons)

Cathedral of Christ the Savior at Borki,

Architect R.R. Marfield, Destroyed in 1943

(Alexei Ivanitsky, Public domain, via

Wikimedia Commons)

In 1894, Alexander III on the Day of

Consecration Exiting the Chapel at Borki

(Alexei Ivanitsky, Public domain, via

Wikimedia Commons)

Perhaps additional Borki items, particularly more medallions by Erik Kollin, Fabergé invoices, or even the train’s complete passenger list will be discovered in the future to further expand our knowledge on this subject. One wonders if Emperor Nicholas II and Grand Duke Mikhail Aleksandrovich still possessed their Borki medallions at the time of their executions in 1918, since it is only logical all the Emperor’s children received one. Nicholas II felt such a strong connection to Borki, even during his wartime travels, he stopped to visit the Cathedral of Christ the Savior at the accident site on April 19, 1915.42 The life-altering events at Borki forever changed Alexander III and his family.

The list of 15 donors engraved on the verso of the two Fabergé imperial triptychs and biographical details about the known recipients for five medallions round out our knowledge of known Fabergé Borki objects and aid in the retelling of this historic Russian event. I extend my heartful thanks and gratitude to each of the personal correspondents and published authors who shared their knowledge and expertise, as well as their willingness to answer challenging questions, to help me uncover new details about these fascinating Fabergé objects and their original recipients.

Readers are invited to share additional information supplementing my in-depth study on Borki medallions with the Romanov Savior theme made by Erik Kollin ![]() , Fabergé’s senior workmaster. Based on the published information studied for the research project, it is estimated 22 of these medallions were presented by Emperor Alexander III and Empress Maria Feodorovna – five to the Imperial Children, 15 to the Fabergé Borki Triptych donors, and one each to the Minister of Ways and Communications, Aide-de-Camp-General, Admiral Konstantin Nikolaevich Possiet (1820-1899), and the Chief Inspector of Russian Railways, Major-General Knut Stjernvall (1819-1889). Five of these medallions have been identified, but at least 17, and perhaps more, are still missing and waiting to be found! Contact: Christel McCanless

, Fabergé’s senior workmaster. Based on the published information studied for the research project, it is estimated 22 of these medallions were presented by Emperor Alexander III and Empress Maria Feodorovna – five to the Imperial Children, 15 to the Fabergé Borki Triptych donors, and one each to the Minister of Ways and Communications, Aide-de-Camp-General, Admiral Konstantin Nikolaevich Possiet (1820-1899), and the Chief Inspector of Russian Railways, Major-General Knut Stjernvall (1819-1889). Five of these medallions have been identified, but at least 17, and perhaps more, are still missing and waiting to be found! Contact: Christel McCanless

1 In the 19th century, the Julian Calendar used in Imperial Russia was 12 days behind the Western Gregorian Calendar. The accident date is listed with the dual dating system, but all other dates prior to February 1918 in this essay are in the ‘old style’ of the Julian Calendar. In February 1918, the Bolsheviks officially adopted the Western Gregorian Calendar.

2 Includes a lengthy letter from Empress Maria Feodorovna to her mother, Queen Louise of Denmark, describing in detail the Borki train accident.

3 Molokhovets, Elena (author), and Joyce Toomre (translator). Classic Russian Cooking: Elena Molokhovets’ – A Gift to Young Housewives, 1998, p. 23. “By the 19th century, increased urbanization, and the influence of European customs caused a change in eating patterns, at least for the wealthier Russians … zavtrak [breakfast] now became a kind of light early lunch …” The Empress refers to having breakfast at the time of the accident (2:14 p.m.) in her letters, but she is in fact speaking of a ‘light lunch’.

4 Nelipa, Margarita. Alexander III: His Life and Reign, 2014, pp. 424-425.

5 Ibid., p. 393.

6 Sotheby’s London (November 27, 2012, Lot 635, £ 253,250) auction catalog description states the icon was made by Ovchinnikov in 1884 and presented in 1888. Pavel Ovchinnikov, the founder of the firm, died in April 1888. Two metal dedicatory plaques applied on the verso of the icon were likely applied later by his sons, who took over the company before the icon was presented to Emperor Alexander III and Empress Maria Feodorovna after the 1888 Borki train accident.

7 In 1054, the ‘Great Schism of the Church’ occurred due to differing theological views and political complexities. The established church separated into two major groups: the Western Roman Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church. The Vernicle is a western theological term describing the cloth St. Veronica used to wipe Christ’s face, whereupon his image miraculously appeared on the cloth. The Mandylion of Edessa, or simply the Mandylion, is the Eastern term for this cloth. In the Eastern version, Christ himself, wipes his face and his features are imprinted on the cloth. Both are images of Christ Not Made by Hands iconographic types, meaning Christ miraculously imprinted his image on the cloth. The imprint of Christ’s visage on the cloth represents the very first icon. Although the term Vernicle is used in the literature to describe the image of Christ on Kollin’s Borki triptychs and medallions, it is not entirely accurate. The image on Kollin’s Fabergé Borki pieces is the Romanov Savior, a variation of the Christ Not Made by Hands theme, distinguished from the others by the crown of thorns on Christ’s head.

8 von Solodkoff, Alexander. The Jewel Album of Tsar Nicholas II, 1997.

9 Recent research suggests Nicholas II paid artists, primarily Baroness Ekaterina Tiesenhausen, to illustrate his jewelry album. Further details, “Jewel Album of Tsar Nicholas II: Research Updated”, Fabergé Research Newsletter, Fall and Winter 2019.

10 Auction house description of Countess Elena Sheremeteva’s medallion. For more details, see endnote 7.

11 Tillander-Godenhielm, Ulla. Fabergé: His Masters and Artisans, 2018, p. 67.

12 Summary of Kollin’s biographical data (Fabergé Research Newsletter, Spring and Summer 2019); Tillander-Godenhielm, Ulla. Fabergé: His Masters and Artisans, 2018, pp. 60-69, 267)

13 Personal correspondence with Wendy Salmond, 11/24/19 and 5/28/22.

14 McCarty, V.K. The Disturbing Beauty in the Face of Christ in the Romanov Mandylion Icon, Sofia Institute Conference, December 2011, p. 18.

15 Personal correspondence with Wendy Salmond, 11/24/19.

16 Tsar Peter I was not created Emperor until October 1721, when he was also given the title, The Great. (Lincoln, Bruce. Romanovs: Autocrats of All the Russias, 1981, p. 164).

17 McCarty, V.K., p. 17.

18 Daniel Brière contributed details for the Donor List, 5/1/22.

19 Gelardi, Julia P. From Splendor to Revolution: The Romanov Women, 1847-1928, 2011, p. 109.

20 Сердце царя – в руке господа, In Russian, Accessed 2/17/20.

21 Топография Гатчинского дворца, In Russian: Accessed 10/14/21.

22 Cyrillic ‘Кн.’ for prince or princess (князь/княгиня) and ‘Гр.’ for count or countess (граф/графиня).

23 Information about the non-titled branch of the Sheremetev family was shared courtesy of The Russian Nobility Association in America, Inc.

24 Krog, Ole Villumsen, Ulstrup, Preben, et al., Treasures of Russia – Imperial Gifts, 2002, No. 15, pp. 243-245.

25 Розанова, Наталия. Царственные Страстотерпцы Посмертная Судьба (Rozanova, Natalia. Royal Passion-Bearers: Posthumous Fate), 2008, p. 327.

26 Personal correspondence with Vladimir Solovyov and Ilya Korovin, 5/16/19.

27 Personal correspondence with Dr. Sergei Nikitin and Peter Sarandinaki, 3/17/20.

28 Vladimir Alekseevich Sheremetev was appointed Major-General of the Suite of His Majesty in 1891, and also remained Commander of His Imperial Majesty’s Own Konvoi until his death in 1893 at age 45.

29 Belyakova, Zoia. Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaevna and Her Palace in St. Petersburg, 1994, p. 230.

30 Christie’s Geneva, November 12, 1985, Lot 315.

31 Emmanuel Ryz examined a library copy of this publication in Paris, France.

32 Booklet (Author Unknown). “Чудо милости Божией. Дивное спасение государя императора Александра Александровича, супруги его государыни императрицы Марии Федоровны и августейших детей их” (The Miracle of God’s Mercy: The Miraculous Salvation of the Emperor Aleksander Aleksandrovich, His Wife Empress Maria Feodorovna, and Their August Children). Moscow, Publishing House of I.D. Sytin and Company, 1888, p. 7.

33 Придворный Календар на 1888 год (Court Calendar for 1888). Publishing House R. Golike, St. Peterburg, 1887; Придворный Календар на 1889 год (Court Calendar for 1889). Ibid., 1888.

34 Op. Cit., Booklet (Author Unknown), p. 26.

35 Mihály Zichy’s original watercolor entitled, Катастрофа 17 октября 1888 года под Борками (Catastrophe, 17 October 1888, near Borki), is in the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg, Item No. P6-14551.

36 Зимин, И. Врач Двора Его Императоского Величества (Zimin, I. Doctors of the Court of His Imperial Majesty), 2016, p. 257.

37 Personal correspondence with Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm, 3/17/20 and 10/21/21.

38 Николай II, Император России. Дневник Ииператор Николая II: 1890-1896 г.г. (Nicholas II, Emperor of Russia. Diary of Nicholas II: 1890-1906), Berlin, 1923, p. 88-89. Emperor Nicholas II’s thoughts recorded in his diary (October 28, 1894): The funerary train carrying the coffin of Emperor Alexander III from Livadia in the Crimea to St. Petersburg stopped at Borki and Kharkov for prayer services (panikhidas).

39 Kulikovsky, Paul, Woolmans, Sue, and Karen Roth-Nicholls (eds.). 25 Chapters of My Life: The Memoirs of Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna, 2014, p. 25.

40 Ротшейна, Ф.А., (ред.). Дневник В.Н. Ламздорфа, 1886-1980 (Rotsheina, F.A., ed. Diary of V.N. Lamsdorf, 1886-1890), 1926, pp. 141-142.

41 Wortman, Robert S. Scenarios of Power: Myth and Ceremony in Russian Monarchy, Vol. II, 2000, p. 290.

42 Nicholas II, Emperor of Russia, Empress Alexandra, and Joseph T. Fuhrmann. The Complete Wartime Correspondence of Tsar Nicholas II and Empress Alexandra: April 1914-March 1917, 1999, p. 122. Telegram from Nicholas II to Alexandra Feodorovna stating, “Shall stop at Borki”. Listed as No. 278/Telegram 3.