Newsletter 2018 Fall and Winter

- Fabergé Research – What’s New?

- Innovative Technological Explorations of VMFA’s Fabergé and Russian Decorative Arts Gallery

- Special Collections in the Freeman Library

- Conservation Lab Study Tours

- Living Memory: A Source for My Research on the Fabergé Workshops

- Fabergé: His Masters and Artisans by Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm (Book Review)

- Fabergé Design Sketches and What They Teach Us

- Cutting the Cord: An Exploration of Fabergé’s Mechanical Bell Pushes

- Fabergé’s Icons

- The (Second) Rise of Fabergé: Imperial Heritage and Cultural Identity

- My Quest for Fabergé Imperial Eggs

- Hillwood Museum Happenings

- Fabergé Rediscovered by Wilfried Zeisler et al. (Book Review)

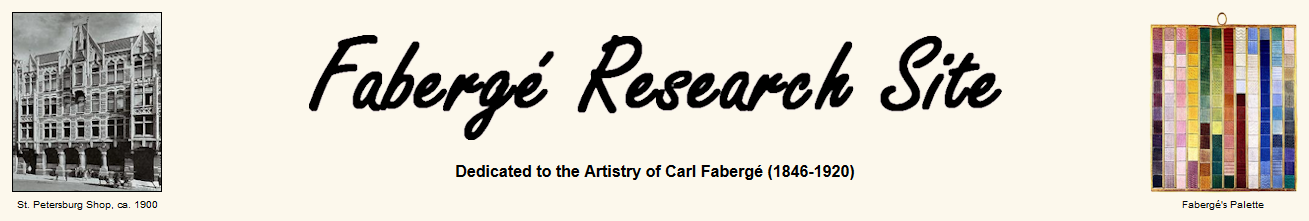

A hundred enthusiasts and scholars from Canada, Finland, France, the United States, donors, and docents attended the Fabergé gathering in Richmond at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (VMFA) on July 27, 2018. Old and new friends met, information was exchanged, and the many compliments shared by the attendees suggest the event was a success! Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm presented the key-note address followed by the tours of the permanent collection in the Fabergé Galleries, special collections in the Freeman Library, and a unique study and discussion tour in the Conservation Lab. The look behind the scenes was new to most Fabergé enthusiasts. We extend a special Thank You! to the VMFA team for hosting this amazing event, our second symposium. In July of 2011, 55 enthusiasts met for the first time ever at the VMFA. On both occasions, a visit to the Hillwood Museum was added for the next day. This time over 35 enthusiasts traveled in carpools to Washington (DC) to visit the brand-new installation, Fabergé Rediscovered, with guided tours by Wilfried Zeisler, chief curator at the Hillwood Estate, Museum & Gardens.

(Courtesy Timothy Adams)

Holding an Original Fabergé

Object – A First for Her!

(Courtesy

George W. Terrell, Jr.)

Scholars and enthusiasts, who shared their knowledge and new research with the attendees at the Fabergé gathering in Richmond, generously contributed summaries of their presentations for this edition of the Fabergé Research Newsletter. We look forward to more such exciting programs in the future.

Richmond Gathering Highlights:

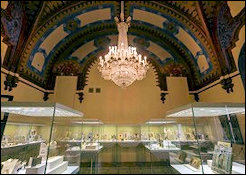

Barry Shifman, Sydney and Frances Lewis Family Curator, Decorative Arts 1890 to the Present, whose duties include the Fabergé and Russian decorative arts collection, welcomed the group and introduced the thematic lay-out for the recently renovated VMFA Fabergé Galleries to the audience. Twyla Kitts, teacher program educator, and Ryan Schmidt, lighting designer, led the tours in the galleries.

Redesigned with a focus on interactive components, the suite of galleries features four large touchscreens allowing visitors to view the intricate construction of the five Imperial Eggs as they open and reveal their interiors. After viewing the collection of Fabergé miniature Easter eggs, visitors can create and share their own design on an interactive application featured discretely throughout the galleries. The mobile application also brings to life the rich fairy-tales featured on various decorative arts and provides an in-depth, historical experience that narrates and enriches the entire Fabergé collection. (Courtesy Marketing Department, VMFA)

(Photograph: David Stover © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts)

(Photographs: Travis Fullerton © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts)

The interdepartmental team involved in the 2016 re-installation of the Fabergé and Russian Decorative Arts gallery at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts faced several challenges. How could we tell the hundreds of stories connected with the objects in this collection without covering every available wall space with didactic panels and label copy? How could we exhibit the five imperial eggs in free-standing individual cases and still provide adequate answers to the many questions our visitors have about these renowned eggs? How could we provide experiences that appeal to visitors of different generations and different interests?

Our solution was to offer layered information using a variety of technologies. Traditional gallery panels and object labels provide basic information about Mrs. Pratt (whose bequest forms the core of the collection), Alexander III and Nicholas II (the last two emperors of Russia), Carl Fabergé and his firm, and the individual objects. These texts also present information about the Old Russian Style that flourished in Moscow, the process of making enamels and carving hardstones, and selected information about a few featured objects.

Touch Screens

For visitors in search of a broader and richer understanding of the five imperial eggs, the four large touch screens in the central chamber of the gallery were installed to provide images, information, and videos. At each screen, visitors may choose each of the five eggs by swiping it into view. Tapping the menu options will then open close-up views of each egg with explanatory texts, archival documents from the Pratt archive, and videos of the eggs being opened and manipulated. This feature is especially important for the Imperial Pelican Egg, which does not contain a surprise inside like the other eggs. Instead, the egg itself unfolds to reveal eight delicate watercolors on ivory in oval frames rimmed with pearls. These scenes represent the educational institutions and charities directed by Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna (1847-1928).

Fabergé App

Visitors also often ask for more information about collection connections with the last two Romanov rulers of Russia, with Fabergé himself, and with Mrs. Pratt. To provide this context, the museum’s interpretation team developed the Fabergé & Russian Culture: Five Pathways app for smartphones and tablets which is available in the device’s app store (Apple | Google). Visitors may also use one of four tethered iPads (illustration 2 above) while comfortably seated on cushioned benches in the gallery’s central chamber. The app offers six initial options listed below. Five choices combine images, quotations, primary source documents, and narrative to tell rich, interconnected stories. The sixth option is an interactive egg design activity:

- Empress Maria Feodorovna: The Matriarch

- Nicholas & Alexandra: The Tragic Love Story

- Fabergé: The Visionary Artist

- Mrs. Pratt: The Avid Collector

- Ivan & the Gray Wolf (Pathway tells a traditional Russian fairy tale and features illustrations by Ivan Yakovlevich Bilibin adapted from a rare book on view in the gallery.)

- Create Your Own Fabergé Egg: Egg Workshop (Activity allows visitors of all ages to create their own virtual eggs using decorative elements drawn from the museum’s collection of miniature eggs designed by the Fabergé firm.)

The Fabergé app is like an anthology of generously illustrated short stories. It is not designed to be consumed during a single visit. Instead, it encourages users to return frequently to enjoy fascinating excursions into the past. During one visit, one might follow the eventful life and untimely death of Empress Maria Feodorovna’s youngest son, Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich (1878-1918). This gallant officer once owned the Statuette of a Sailor on view in the hardstone section of the gallery. Next, one might investigate the innovative business practices that transformed the small Fabergé firm into a leading international enterprise. You might even learn what the Fabergé Gum Pot contained and how the Bell Pull works.

What about Mrs. Pratt? How did her purchase of a single Russian silver-gilt fork from Lord & Taylor’s department store in 1933 result in the ownership of five imperial Fabergé eggs? This pathway includes newly discovered photographs of Mrs. Pratt, along with glimpses of Chatham Manor, her historic home in Fredericksburg, Virginia.

Another visit might reveal how the love story of Nicholas and Alexandra unfolded alongside the stories of starving peasants, devastating wars, and violent revolution. How is Fabergé’s Star Frame connected with the brutal execution of the last tsar and his family? Users can discover the answer by viewing the section called 1918 – The Romanov Family Is Executed.

Website

We invite you to visit the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in person to see our great collections, or why not begin your adventure with 306 Fabergé objects on our website.

Twyla Kitts is the Teacher Program Educator at VMFA, and serves as the collection educator for the Fabergé and European art galleries. She developed the content for the 2016 mobile application Fabergé at VMFA, and contributed an article to Fabulous Fabergé: Jeweler to the Czars, the exhibition catalog published by the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts in 2014. She is the recipient of the Virginia Art Education Association Art Educator Award (2014), Virginia Council for the Social Studies Friends of Education Award (2017), and has served on Virginia DoE’s Standards of Learning Review Committees for Visual Arts and History.

the Next Generation

(Photograph by Richard Parrow)

(Photograph: David Stover © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts)

(Donated by Jeff Eger,

Photograph by Courtney Tkacz)

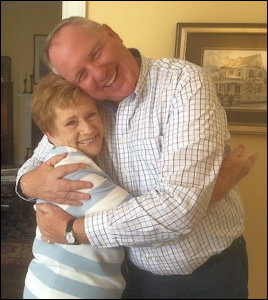

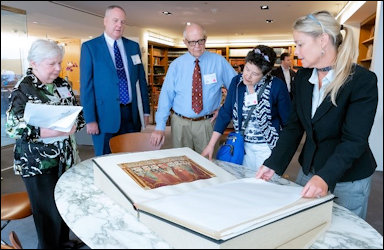

Lee Ceperich, the Director of the Freeman Library, welcomed the visitors to the Reading Room and gave an overview of all of the primary source and research materials that had been selected for viewing. The visitors took great interest in the variety of items shown during the three tour rotations, and asked insightful questions about what they saw and read.

The tables each offered a different assortment of materials:

- Letters, invoices, price tags, and newly discovered photographs from the Lillian Thomas Pratt archives (above left)

- Two vanity photo albums prepared for Mrs. Pratt, one featuring her Fabergé collection and the other featuring members of the Russian imperial family

- Russian folk tales, books, and postcards beautifully illustrated by Ivan Bilibin

- Selection of Fabergé related items and research files donated by Christel McCanless, and

- The very large and lavishly illustrated Coronation Album of Alexander III and Maria Feodorovna, one of the finest treasures of the library’s collection (middle above).

Undoubtedly, the highlight of the tour was the auction catalog table (above right). Catalog dealer Jeffrey Eger graciously donated 185 pounds of Russian works of art catalogs from 1973-1986 for the participants to take home. Almost all of the attendees loaded their bags up with these goodies and will hopefully put them to good research use back home.

The Freeman Library would like to thank the organizer of the event, Christel McCanless, for suggesting the registration fee be donated to the library so we can continue to purchase important primary source and research materials about Fabergé and Russian Decorative Arts.

Courtney Tkacz is the Archivist at VMFA. She is responsible for managing all of the permanent records at the VMFA, including institutional records from over 25 museum departments, thousands of artist and subject files, hundreds of museum publications, and special collections related to the museum and the history of art in Virginia. Courtney has a BA in Medieval and Renaissance Studies from Washington & Lee University, and an MLIS in Public and Academic Librarianship from the University of Pittsburgh and joined the VMFA staff in 2003.

The Sculpture and Decorative Arts Conservation Lab at the VMFA is responsible for the conservation of the three-dimensional artworks in the museum, including everything from large outdoor sculptures to small decorative arts objects such as the Fabergé collection. Conservators in our lab have cleaned and repaired many of the Fabergé objects in preparation for exhibitions at the museum and traveling abroad. We travel with the collection when the objects go on exhibition at other institutions. I went with the collection to Beijing in 2016 to ensure the objects traveled safely and were in good condition for installation at the Palace Museum.

During the Fabergé gathering, our guests looked at 20 pieces of Russian and French Decorative Arts objects displayed on tables in the conservation lab with our visitors. The objects included many by Fabergé and Cartier, as well as other unknown artists and firms, including some forgeries. The objects sparked interesting discussions among the participants. Marilyn Swezey, for example, commented that the icon (47.20.7) was of particular note as it was signed by Keibel and was made to be presented at the birth of the Grand Duchess Tatiana based on the inscriptions. She suggested it really should be on view because of its significance and very fine quality.

Barry Shifman discussed two frames produced as forgeries, one marked for Karl Hahn. He noted the applied silver swags were quite notably weaker than those on the Fabergé-produced objects such as the rock crystal, gold, and enamel parasol handle (47.20.188) on the table nearby. Participants were given the opportunity to identify other authentic and Fauxbergé objects with great success. Overall it was a wonderful learning experience for all involved, myself included.

Ed. Note: Ms. Harrison was kind enough to share her two handouts for this newsletter. Test your knowledge!

Ainslie Harrison is the Assistant Objects Conservator in the Sculpture and Decorative Arts Conservation Lab at VMFA. She received her MA in Art Conservation from Queen’s University and went on to hold fellowships at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Penn Museum, the National Museum of the American Indian, and the Smithsonian’s Museum Conservation Institute. She also worked as an archaeological conservator at sites in Turkey and Panama, and was an objects conservator at the National Museum of American History.

It was my honor to be the keynote speaker for the Fabergé Gathering at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond this past July and to present my new book, Fabergé: His Masters and Artisans.

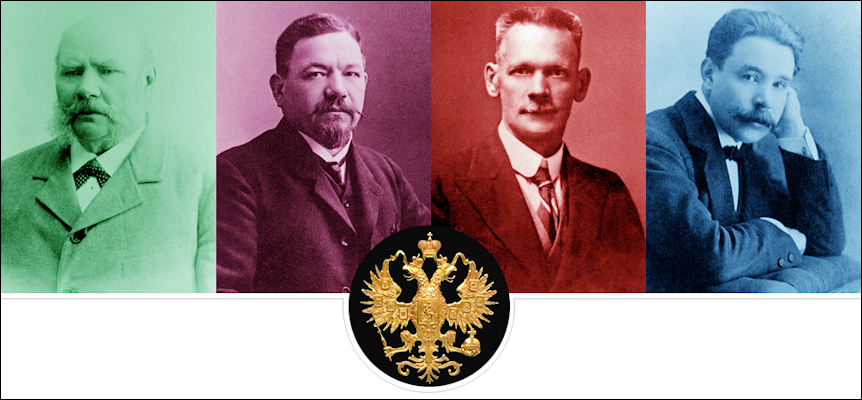

Hjalmar Armfelt, Master Gold- and Silversmith (Active 1904-18), Albert Holmström, Chief Jeweler (1903-18)

(Author’s Collection)

While preparing my address, it occurred to me that the unique surroundings into which I was born were a topic worth sharing with my audience. My personal milieu was – and still is – the goldsmiths’ trade of Helsinki. Until the early 1980s, its St. Petersburg heritage from the time of the Russian Empire was scrupulously nurtured and preserved, and the old flame kept very much alive in my country.

Practically every jeweler, goldsmith, or silversmith, not only in the capital of Helsinki, but throughout Finland as a whole, had traditions stretching back to St. Petersburg, which was founded in 1703. Their fathers or their grandfathers had either trained in St. Petersburg, had qualified as master craftsmen there, or had headed their own workshops in the great city. What was common to all was they had returned to Finland, their country of origin, at the time of the Russian Revolution. Another common feature was the living memory these craftsmen had retained from St. Petersburg. The preservation of distinctive techniques and working methods common to most workshops in the decades leading up to the demise of the Russian Empire in 1917 was an important part of this memory in action.

Recognizable imprints of this were the variety of shades of gold (especially the saturated “red” copper-rich alloy that was used unsparingly), finely chased mounts, and detachable suspension loops or pins for easily transforming a pendant into a brooch. Even the unique fastening mechanisms echoed the workshops and ateliers of St. Petersburg. These special techniques provided ingeniously simple safety devices keeping the jewel from accidentally falling off a garment. The design of fine jewelry made in great quantities until the late 1950s at A. Tillander, our own family firm-for whom many of the former Petersburg masters worked-was closely reminiscent of the garland-style diamond jewelry created in the workshop of Albert Holmström, the chief jeweler of Fabergé from 1903 to 1918. This actually comes as no great surprise, for the originator Oskar Pihl was brother and nephew respectively to Holmström’s two female designers, Alma Pihl and Alina Holmström.

Until the late 1950s, Russian was spoken in many of the Finnish workshops, more for nostalgic reasons than any other. With the gradual influx of a younger generation of non-Russian-speaking craftsmen in the workshops, the Russian language was transformed into a playful vernacular only insiders understood – but it was interspersed with technical terms in the various languages used in the St. Petersburg workshops. Uuno Aarne, son of Fabergé’s workmaster Viktor Aarne, has assembled a list of these terms in his admirable handbook for goldsmiths, clarifying from which language the terms originate (whether Russian, German, French, Finnish, or Swedish).1

Reminiscences, both verbal and written, family photographs, letters, and other documents abound in the private archives of the emigrants from St. Petersburg, forming a further essential strand of the living memory underpinning of my research. These have been an important source of material for documenting the lives and careers of the craftsmen working for Fabergé and his contemporaries. Part of this is the veritable treasure-trove of St. Petersburg jewelry and works of art in precious materials preserved in the former Grand Duchy of Finland. These original jewels are still cherished by the descendants of their original owners, many of whom were habitués and regular patrons at Carl Fabergé’s premises at 24, Bolshaya Morskaya.2

| 1 | Aarne, Uuno V., et al. Kultasepän käsikirja. (The Handbook for a Goldsmith). Helsinki: Suomen Kultaseppien Liitto, 1945, p. 619. |

| 2 | Tillander-Godenhielm, Ulla. Jewels from Imperial St. Petersburg. St. Petersburg, La Berlière and London: Liki Rossii, Images de Russie and Unicorn Press Ltd., 2012. |

A 2018 publication about Carl Fabergé and his workmasters – actually an augmented English translation of the 2011 Finnish-language publication, Fabergén suomalaiset mestarit (Fabergé’s Finnish Workmasters) – by Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm has again contributed important information and insights into the workings of the famed Fabergé firm. Unfortunately, the majority of Fabergé scholars and enthusiasts do not read Finnish so this English translation is a vital addition to the Fabergé scholarly corpus. Nonetheless, it is more than a dry scholarly compendium of names and dates. The author brings to life the work and lives of the workmasters who contributed their talents to the splendor of Fabergé, using riveting stories from quoted memoirs and her recollections from interviewing descendants, all of them supplemented with beautiful photographs of their handiwork. The lives recounted here, especially of the Finnish-born goldsmiths, reflect the economic and historical travails of the late 19th and early 20th century Russian empire, which included Finland.

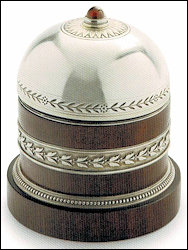

Ms. Tillander-Godenhielm has excerpted sections from the private memoirs of Hjalmar Armfelt (active 1904-1918), giving the reader insights into the motivations and actions of the apprentices who rose through the ranks to become master goldsmiths and owners of their own workshops. The sufferings of these craftsmen after 1918 (when the Fabergé firm closed) and their survival during times of deprivation and terror stir sympathy in the modern reader. For many of these workmasters their original birthplace of Finland became their final refuge. It is ironic they left their birthplace to seek a better and more prosperous life only to have to return home after their life in Petrograd (today St. Petersburg) turned toxic. The author highlights Fabergé’s collaboration with women in both the design and production of his luxurious objects. Two of his major female designers were Alma Pihl for the 1913 Winter and 1914 Mosaic Eggs, and Alina Holmström, who specialized in ornamental jewelry. Two workshops, which furnished the majority of their production to Fabergé, were headed by women, who after their husband’s deaths, took over the existing workshops: Anna Ringe (active 1894-1908), whose atelier supplied small enameled objects in gold and silver, and Matilda Kaki (active 1896-1911), whose studio made all of the wooden boxes encasing the finished objects, and the wooden carcasses for bell pushes, cigarette cases, frames, etc.

The intersecting relationships among the workmasters (both within the Fabergé firm and contemporary Russian jewelers and silversmiths) are enumerated. One example is the fact that Mikhail Perkhin (active 1886-1903) was married to the daughter of Vladimir I. Finikov, chief workmaster for the renowned Bolin Swedish jewelry firm also in St. Petersburg. Perhaps this relationship cushioned the decision to hand over Perkhin’s firm to his assistant Henrik Wigström after his death in 1903. Readers gain an understanding of why certain types of objects were produced by particular workshops, based on the movements of the workmasters. Thus, mechanical bell pushes had been made by Antti Nevalainen (active 1885-possibly to 1910, additional research in progress) and his assistant Hjalmar Armfelt (working for Nevalainen from 1896-1904), who continued to be the chief maker of these objects after he acquired Viktor Aarne’s workshop in 1904. He must have learned to make this item at Nevalainen’s.

This unique volume is an important contribution to Fabergé literature notably for the light it sheds on the workmasters, but also the lavish illustrations of quintessential Fabergé objects from Imperial eggs to bell pushes, and the images of the workmaster’s hallmarks. There is also a helpful listing of contemporary Russian firms and jewelers who competed in the same market as the Fabergé firm. All scholars and enthusiasts will welcome with open arms this extremely helpful English edition, complete with fascinating new information about Fabergé’s Finnish workmasters.

Dr. Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm is a member of the 4th generation family business, Jewellers A. Tillander, located in Helsinki, Finland, which was founded in St. Petersburg by her great-grandfather in 1860. She has a BBA in business administration, and a PhD in art history. Her special research and publishing interests are the St. Petersburg goldsmiths and the art of the 18th to 20th centuries. Among her numerous publications is her doctoral dissertation, The Russian Imperial Award System, 1894-1917, published in 2005.

Three main types of design sketches or drawings were created by the design staff in the Fabergé firm. Each type had a distinctive purpose in the production process. Knowing the purpose of the designs allows more detailed provenance research to take place even a hundred years after the pieces were made.

- Working Drawings (A.) were for the craftsmen to use while creating an object, and often had cost or other annotations written on the drafts. One working drawing of a tea set (B.), sold at auction in 1989, has a handwritten notation “Yusupov pot” (the Yusupovs were a prominent noble family). It adds important provenance to the set not known when it sold at auction nine years earlier.

- Production Drawings (C.) were drawn into the production albums to document the final product upon completion. The albums were not only a record of what was made, but were also used as inspiration for future pieces.

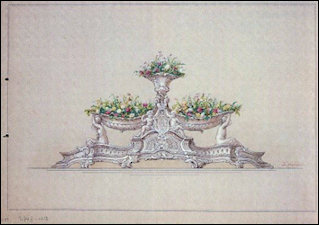

- Client Approval Drawings (D.) were the only drawings seen outside of the workshops. They were created on “speculation” in hopes that a client would like the piece and commission it to be made by Fabergé’s workmasters. Many designs were drawn for the Imperial Cabinet, but not all were approved for production.

B. Julius Rappoport Working Drawing of Yusupov Tea Set with Designs (Christie’s, London, April 27, 1989, Lot 438, p. 61)

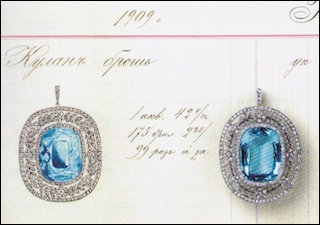

C. August Holmström Production Drawing for Aquamarine Pendant and Finished Product (Tillander-Godenhielm, Ulla, Fabergé: His Masters and Artisans, 2018, p. 139)

D. Fabergé Client Approval Drawing of a Surtout de Table from the State Hermitage Archives (von Habsburg, Géza, Fabergé Imperial Jeweler, 1993, p. 410)

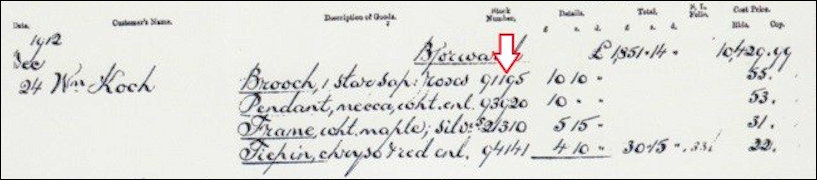

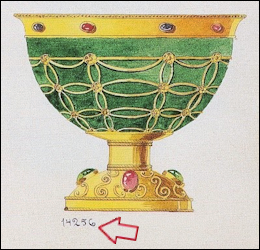

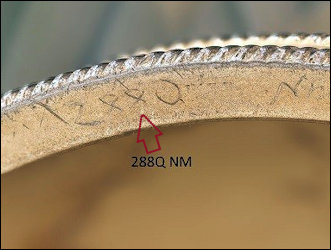

A Production Number (14256, illustration G.) was assigned to a piece and then added below the drawing in the production albums. It originated from the “white paper” or envelope that came preprinted with a number from the manufacturer. The materials used in the making of an object, such as loose stones, as well as their size and costs, could be recorded for future reference in case a stone was lost and needed to be replaced. The paper then folded up into an envelope containing the gold findings, loose stones, and other materials needed by the craftsmen to create the piece. The production number traveled with a specific piece throughout its creation and was then logged into the production album with the final drawing. Once the piece was ready to sell on the retail floor, it received a scratched Stock Number (E.) which was entered into the sales ledger when the piece was sold. Only the London Sales Ledgers are extant, but the same numbers can be found on original Fabergé invoices in Russian archives (RGIA). The production number and scratched stock number by Fabergé are frequently confused, and mistakenly cited as an inventory number. It is important to understand that objects may have both numbers, one for the manufacturing side of the firm and the other for the retail side.

An example of a production number (G.) and a new wrinkle of a Dealer Stock Number (H.) emerged during my research for this presentation. I found a nephrite cup (F.) in the Pratt Collection at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, with a matching drawing (G.) in the Wigström production album with a production number. But it had not one, but two scratched numbers on its base. The museum has no information or provenance for this piece. I sent the museum’s photographs to my friend Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm and asked her if she knew what this second set of numbers might be. She suggested it might be a dealer’s “stock number” inscribed at a later date, and she was aware Wartski, an antique dealer in London, used this particular practice at one time. Kieran McCarthy of Wartski recognized the number as one of theirs from the mid-1920’s. Thus, we now have a piece of the provenance for this cup but other questions remain. Did Mrs. Lillian Pratt purchase it from Wartski’s in the 1920’s? It would make it the earliest piece she purchased. Or had the object traveled to other collections and dealers before it ended up in her collection? More research can now be pursued for this lovely nephrite and gold cup.

G. Wigström Production Drawing with Production Number of the Nephrite and Gold Cup (Tillander-Godenhielm, Ulla, Golden Years of Fabergé, 2000, p. 123)

H. 288Q NM, Wartski Stock Number on Bottom Rim of Wigström Nephrite and Gold Cup (Courtesy of Virginia Museum of Fine Arts)

Timothy Adams is an independent art historian and gold work scholar. He serves on the Editorial Review Board for the Gemological Institute of America and writes books reviews for its Gems & Gemology Journal. He is a Curatorial Consultant for the Decorative Arts at the Bowers Museum in Southern California, and lectures for museums and private institutions on historical gold work traditions. His specialty is the artwork of the Russian jeweler Carl Fabergé.

Silver-gilt Enamel Bell Push, Chalcedony Push, 88 Silver, St. Petersburg,

1899-1904, Antti Nevalainen, Stock Number 12746

(Author’s Collection)

Silver-gilt Enamel Bell Push, Moonstone Push, 91 Silver, St. Petersburg,

1904-1908, Hjalmar Armfelt

(Muhin, V.V., The Great Fabergé, 1989, Catalog #5, pp. 66, 120, 128)

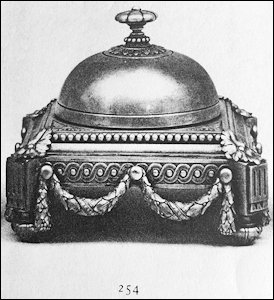

The jewelry firm of Carl Fabergé is today well-known for designing elegant and novel bell pushes or call bells. The notoriety accorded these objects of utility is out of proportion to their numbers among the items of decoration (jewelry and objets d’art) produced by the jewelers from 1890 to 1917. It has been estimated the company’s shops produced over 200,000 items during their existence. Unfortunately, the sales ledgers for the St. Petersburg, Moscow, Odessa, and Kiev branches are lost. The surviving London Sales Ledgers, the design notebooks from the workshops of August and Albert Holmström (active 1857-1918) and Henrik Wigström (active 1903-1918), Fabergé invoices to the Imperial family, and the artifacts themselves give some idea of the breadth and number of items produced. The London branch sold around 10,000 items from 1906 to 1917, but of that number, only 127 were bell pushes or 1.3%. Miniscule!

Silver, Moscow, circa 1890, Julius Rappoport

(Sotheby’s New York, June 17, 1982, Lot 254)

Bell Push Production Estimates

2% of the 200,000 objects created = 4,000 bell pushes

35,000 known Fabergé items = 700 bell pushes extant

Author’s estimate = 500 in 2001

One can safely say a bell push is not a common Fabergé object in the same way a miniature pendant egg, cigarette case, or photograph frame is. Perhaps we are more aware of “call bells” than their actual production warrants because a large number of them have survived. Why? They were not easily melted down for the value of their metal and the gems decorating them, and the combination of unique designs with luxurious materials masks a pedestrian function – calling servants and staff.

A brief chronology of bell-push production drawn from the published literature shows Fabergé bell pushes “flew under the radar”:

- 1935: First Western exhibit of Fabergé’s work after the Russian Revolution in London included two – one loaned by Queen Mary (Queen Consort of Great Britain, 1910-1936) and the other by Wartski London, an antique dealer trading in silver, jewelry, and Fabergé, established 1865.

- 1949: H.C. Bainbridge, the London Fabergé branch manager from 1906 to 1917, did not mention or illustrate them in his 1949 monograph on Fabergé1, which rekindled the enthusiasm for Fabergé in the West.

- 1953: A. Kenneth Snowman, proprietor of Wartski, included them for the first time in his study of Fabergé, with six illustrations.2 He writes: “Some table-bells were designed to ring by means of a clapper when pressed.” He mentions Fabergé produced mechanical and electric ones, yet call bells were never explored further in subsequent Fabergé studies or exhibition catalogs, even though they were shown in museum exhibitions.

- 2000: Mechanical and electric examples were studied in a groundbreaking article on Fabergé bell pushes published by Magazine Antiques.3 In the article, I incorrectly stated the workmasters Antti Nevalainen (active 1890-19174) and Hjalmar Armfelt (active 1895-1918) were the only Fabergé workmasters5 producing mechanical examples. Since then, I have learned Julius Rappoport (active 1890-1909)6 made at least one silver mechanical bell push around 1890 (shown above).

Mechanical or clockwork bell pushes date from about the middle of the 19th century. Snowman in his 1953 monograph on Fabergé distinguishes the electric bell push from the mechanical one by explaining the latter ring by means of a clapper striking the interior side of the bell. More complex mechanical types known as clockwork bell pushes have a clock mechanism – or striking bell – that utilizes a complex series of gears often powered by a mainspring. Energy is stored in the mainspring manually by winding it up. Most of the surviving examples are wound by hand, through turning or rotating the top silver bell. When the push piece is pressed, it releases the gear, which makes the ringer strike the bell. Most of the bell pushes known to have been crafted by the Fabergé firm are electric, however. Very few mechanical examples were made, and the clockwork type were even more rare.

A few details have emerged in my study of bell pushes over the years that put the electric bell pushes into their historical context.

- Electricity was introduced to Russia in the early 1880’s.

- The first electric street lights were installed at Gatchina in 1881.

- St. Isaac’s Cathedral was illuminated with incandescent lamps in 1882.

- In 1883, the Nevsky Prospect was illuminated.

- 1886 saw the formation of the first electric company7 in St. Petersburg.

- However, there was no real domestic consumption of electricity until 1890.

- The first evidence of an electric bell push was in 1891.

In 1891, Grand Duke George Alexandrovich (1871-1899) and Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna (1875-1960), children of Emperor Alexander III, purchased a three-chick bell push for 180 rubles. It was probably made by Julius Rappoport, who at that time made all the Fabergé animals fashioned in silver. The details of the electrical bell push are recorded in a surviving invoice.8 Alexander III had installed electricity at the Gatchina Palace (one of the family’s primary residences) at some point in 1881.9 As yet there is no evidence this bell push has survived. It was probably a gift, but the recipient is not known. There was still a need for mechanical bell pushes in the early years of 20th century in Russia, however, since very few private homes had access to electricity. St. Petersburg had 19,659 subscribers to its electric company in 1908, which increased to 78,035 by 1913. Given that the population of St. Petersburg was 1.9 million in 1913, the number of subscribers was small.10

Examples of mechanical bell pushes discussed below are from the Fabergé studios headed by Antti Nevalainen (active 1890-1910)11 and Hjalmar Armfelt (active 1895-1918).

B. View of the Clock Work Mechanism (Courtesy of the Author)

C. Informal Photograph of Nicholas II and Grand Duchess Elizabeth “Ella” with Bell Push at the Lower Dacha at Peterhof, circa 1900. (Moehrke, Mark, Editor, Unknown Fabergé: New Finds and Re-Discoveries, 2016, p. 20)

(Guzanov, A., and R.R. Gafifulin, Fabergé Items of Late XIX-Early XX Century in the Collection of the State Museum Pavlovsk, 2013, p. 234)

Interesting provenance details discovered for the Nevalainen Imperial bell push:

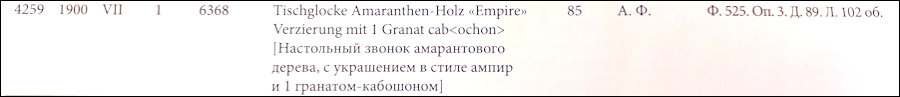

Height: 3.75 inches. Diameter: 4 inches, 1900. Marked with workmaster mark ![]() , 88 Russian silver standard with kokoshnik for St. Petersburg, 1899-1904. Assayer’s mark for Yakov Lyapunov and scratched stock number 6368. Archival details from the sales invoice summary (D.) confirm the bell push was purchased in July 1900 by Empress Alexandra Feodorovna for 85 rubles: Table bell, amaranth wood, “Empire” decoration with one garnet cabochon. (For comparison, Hjalmar Armfelt, chief assistant to Nevalainen, was paid around 80 rubles a month in 1897.)

, 88 Russian silver standard with kokoshnik for St. Petersburg, 1899-1904. Assayer’s mark for Yakov Lyapunov and scratched stock number 6368. Archival details from the sales invoice summary (D.) confirm the bell push was purchased in July 1900 by Empress Alexandra Feodorovna for 85 rubles: Table bell, amaranth wood, “Empire” decoration with one garnet cabochon. (For comparison, Hjalmar Armfelt, chief assistant to Nevalainen, was paid around 80 rubles a month in 1897.)

A photograph (C.) probably taken by the Empress herself) shows this very bell push on a tea table located on a balcony of the Lower Dacha at Peterhof around 1900. Even though this summer home of the Imperial family would have been electrified during the renovation and additions of 1896, there was still a need for a mechanical bell on the balconies and terraces without electrical outlets. Servants waiting in adjoining rooms or at the bottom of the stone steps leading to the terrace would need to hear the bell. Therefore, the clockwork mechanism, more substantial and louder than the sound produced by the simple clapper striking the interior of the silver bell, was preferred. The “Empire” decorative style was very much in favor with Nicholas and Alexandra. The composition of wood and silver, rather gold and enamel, exemplifies the simpler style the couple favored at their summer villa on the Gulf of Finland.

Hjalmar Armfelt bell pushes (**You guessed it! The green bell push is the mechanical one!):

91 Silver, St. Petersburg, 1904-1908,

Hjalmar Armfelt

(Courtesy Hermitage Museum)

Monogram of NII and 1912, Silver,

St. Petersburg, 1908-1917,

Hjalmar Armfelt

(von Habsburg, Géza, Fabergé Imperial

Craftsman and His World, 2000, p. 280)

The green bell push12 in the Hermitage Fabergé Collection is attributed to Viktor Aarne in the published literature, however, the more likely workmaster is Hjalmar Armfelt (active 1895-1918). The mechanical bell pushes made prior to circa 1906 are a little clunky. Many of Fabergé’s clientele owned heavy silver hand bells for calling staff, but the “novelty” of having an elegant and decorative call bell that looked more discreet and took less energy-one just had to press a finger on the push-piece-was appealing. The mechanical bell pushes, such as the green one above, closely mimic the electric ones that Fabergé more commonly produced.

The silver clockwork type engraved with the crowned monogram of Nicholas II is in the “Empire” style and reminiscent of the Nevalainen designs used on the wood and silver clockwork one purchased by his wife in 1900. In the catalog for the 2000 Fabergé exhibition in Wilmington, Delaware, it is suggested Emperor Nicholas II used this silver one when traveling by train.13 No records have been found to confirm this, or the engraved 1912 date.

My preliminary conclusions:

- Some of the first mechanical examples of Fabergé bell pushes were made by Nevalainen, who employed Armfelt as his chief assistant from 1897 to 1904. Armfelt, with Karl Fabergé’s blessing, purchased Viktor Aarne’s workshop in 1904. Undoubtedly Armfelt learned how to make mechanical bell pushes in Nevalainen’s workshop.

- Of the approximately 17 mechanical examples I have found in my research, only seven had clockwork mechanisms. The latter type was more expensive than the electric ones, even if the same materials were used, i.e., silver and enamel.

- Mechanical bell pushes by Fabergé are relatively few in number since they were not “novel” items and did not fit the desire for the latest in technology (electricity) by the firm’s clientele. I would appreciate information on additional examples of Fabergé mechanical bell pushes in order to expand our knowledge of this rare item in Fabergé’s oeuvre. Contact: James Hurtt

James Hurtt is an independent researcher whose chief interest is in Imperial Russian culture from the late 18th century to the “Silver Age,” ending in 1917. His special focus is on Russian silver and enamels, especially those produced in St. Petersburg from 1870-1917. His professional career started in librarianship and he later worked in the publishing industry. In August 1984, he visited the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, in 1988 he acquired his first piece of Fabergé – a silver dessert spoon. In 1991, he added the first bell push to his twenty-piece collection, a Henrik Wigström enameled bell push originally sold by the London Fabergé shop to the Earl of Bathurst on July 9, 1908.

| 1 | Bainbridge, H. C. Peter Carl Fabergé, Goldsmith & Jeweler to the Russian Imperial Court & Principal Crowned Heads of Europe, 1949. |

| 2 | Snowman, A. Kenneth. The Art of Carl Fabergé, 1953, p. 58. (Ed. note: In the 1953 edition published by the Boston Book & Art Shop, fourteen bell pushes are illustrated, but the index only lists eight. Subsequent editions have similar errors.) |

| 3 | Hurtt, James. “Fabergé Bell Pushes,” Magazine Antiques, October 2000, pp. 554-561. |

| 4 | Recent research suggests the closing date for the Nevalainen studio is possibly 1910. |

| 5 | Tillander-Godenhielm, Ulla. Fabergé, His Masters and Artisans, 2018, pp. 174-181, 208-223. |

| 6 | Ibid., pp. 234-235. |

| 7 | Obshchestvo Elektricheskogo Osveshcheniia (Company for Electric Lighting), commonly known as the 1886 Company, with a basic capital of one million rubles was founded in 1886. (Coopersmith, Jonathan. The Electrification of Russia, 1880-1926. Cornell University Press, 1992, p. 48) |

| 8 | Guzanov, A. and R.R. Gafifulin. Fabergé Items of Late XIX—Early XX Century in the Collection of the State Museum of Pavlovsk, 2014, p. 150, #2248. |

| 9 | Courtesy of Joanna Wrangham, an independent researcher who specializes in studying the Imperial Palaces of St. Petersburg. |

| 10 | Coopersmith, Jonathan. The Electrification of Russia, 1880-1926. Cornell University Press, 1992, p. 57. |

| 11 | See footnote 4. |

| 12 | Muhin, V.V. The Great Fabergé, 1989, Catalog #5, pp. 66, 120, 128. (December 2018: Correct workmaster identification pending.) |

| 13 | von Habsburg, Géza, Fabergé Imperial Craftsman and His World, 2000, p. 280. |

One Hundred Years of Russian Icons in St. Petersburg

B. Bedroom of Nicholas II in the Winter Palace, St. Petersburg, Russia, 1917. (Tatiana Pashkova, “Kvartira” Nikolaia II v Zimnem Dvortse [St. Petersburg: Gosudarstvennyi Ermitazh, 2012])

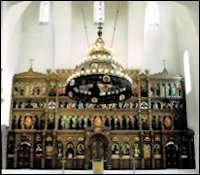

C. Icon Display in the Gothic Hall, Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. (Photograph by Yuri Molodkovetz, 2018, Courtesy Fabergé Museum)

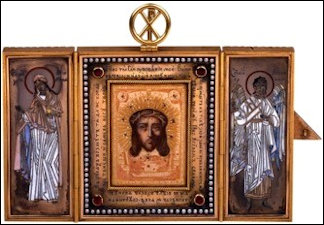

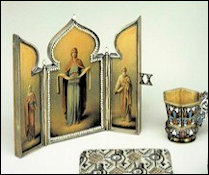

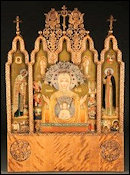

Icons – the sacred images used in prayer by Orthodox believers (A.) are rarely the first items Fabergé enthusiasts think of when they consider the wealth of luxury goods the firm produced.1 The classic texts – Snowman, Bainbridge, Habsburg and Solodkoff – include at most a sentence or two on the subject. The memoirs of Franz Birbaum, a chief designer for the firm from 1893 to 1918, provided the first clue religious objects had been a significant part of the output of Fabergé’s Moscow branch.2 But in the wake of the 1917 revolution the icons produced by the firm were virtually eclipsed by the Easter eggs, hard-stone objects, picture frames, boxes, and countless knick-knacks that had so delighted the Russian elite. Only in the past several decades has a lively auction market brought more icons to the fore, which have often sold for fabulous prices as Russian collectors have vied to possess a piece of the Imperial past. Some of those purchases can now be seen in the Gothic Hall (C.) of the Fabergé Museum in St. Petersburg, an important part of Viktor Vekselberg’s Link of Times Foundation repatriation efforts.

In a Russian 2013 interview, Valentin Skurlov put the firm’s output of icons at over a hundred.3 A survey of auction and museum catalogs conducted over the past year confirms this estimate, and has expanded it to around 132.4 There are certainly more to be discovered, as Romanov descendants or their executors offer these cherished émigré memorabilia for sale. The icons we can document run the gamut from one-of-a-kind imperial presentation triptychs to miniature personal icons. In the variety of both their painting and their metal adornments (the covers or oklads) they represent a fascinating microcosm of icon production in the late imperial period.

In partial explanation of why icons make up such a small part of Fabergé’s extant production, Skurlov and others have pointed to the Bolshevik regime’s destructive policies toward the Orthodox Church in the 1920s. The catastrophic Volga famine of 1921-2 provided the pretext for a campaign to confiscate church valuables, during which many icons and other ritual church items were stripped of their gold and silver metal covers and jeweled adornments. We will likely never know how many Fabergé icons were among the thousands consigned to the storerooms of Gokhran, the State Treasury, to be rendered down for their precious raw materials. Fortunately, we have access to at least some of those icons by Fabergé (and other firms) that once hung in the imperial family’s private apartments in the Winter (B.), Anichkov, Alexander, and Gatchina palaces.

Beginning in 1929, they were among the goods earmarked for export to the United States by Antikvariat, the antiques branch of the Ministry of Trade, using art dealers Armand Hammer and Alexander Schaffer as intermediaries. As a consequence, a number of Fabergé icons with imperial provenance have ended up in American museums (for example, Hillwood Estate, Museum & Gardens, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts) and in private collections. Many icons with an imperial past will likely have a provenance similar to that of the triptych Grand Duchess Elizaveta Fedorovna gave to her sister Princess Alix of Hesse, the future Empress Alexandra Fedorovna, on the occasion of her wedding to Nicholas II in 1894 (D). Consigned to the United States by Antikvariat, the triptych was sold by the Armand Hammer Galleries to Mrs. William Roebling, Jr., in the early 1930s. It then passed to the Forbes Magazine Collection and was finally purchased by the Link of Times Foundation. Today it is among the star exhibits at the Fabergé Museum in St. Petersburg.

Wedding gift from Grand Duchess Elizaveta Fedorovna to her sister Princess Alix of Hesse,

the future Empress Alexandra Fedorovna.

(Forbes, Christopher, and Robyn Tromeur-Brenner. Fabergé: The Forbes Collection, 1999, pp. 228-30, 290)

A quick survey of Fabergé icons allows us to make a few initial observations. First, approximately two-thirds were made in Moscow, of the 49 with a scratched stock number 35 bear Moscow marks. Among the most beautiful and “Muscovite” of these are icons from the workshop of Fedor Rückert (1840-1917), with their distinctive filigree and cloisonné enamel inspired by Moscow enamellers of the 17th century (E). The images they adorn similarly look back to the finely painted icons made during the reigns of the first Romanov tsars in the Kremlin Armory Workshops, where the traditions of Stroganov icon painting were refined to a state of elegant perfection. The workshop of Vasily Gurianov (1867-1920), who earned the singular honor of being appointed icon-painter to Nicholas II, specialized in supplying the Fabergé firm with traditionally painted icons. But Gurianov was just one of several natives of Mstera, a center of traditional icon painting, who produced sacred images “in the old style.”

A number of the icons from St. Petersburg were made in the workshop of Viktor Aarne (1863-1934) and his successor Hjalmar Armfelt (1873-1959), who took over the business in 1904. Aarne and Armfelt produced some icons in the conservative Old Russian Style made popular under Alexander III, but more typically they favored the academic realism taught in the Academy of Fine Arts’ icon-painting workshop and were inspired by the wall paintings in St. Isaac’s Cathedral. The oklads-often no more than a simple narrow picture frame-draw on the classical design repertoire of palmettes, Greek keys, and egg-and-dart. Others recall Renaissance frames with the use of cabochons set in graceful scrollwork (F).

Icons from the Moscow and St. Petersburg Fabergé Workshops

F. Icon of the Kazan Mother of God, Workmaster Hjalmar Armfelt, Fabergé, St. Petersburg, 1908-1917. (Sotheby’s London, 26 November 2013, Lot 771)

While the inventory of Fabergé icons will no doubt continue to grow, it is unlikely to prove that icons were anything but a sideline for the firm, comprising occasional prestige commissions from its imperial clients or other clients with the resources to order a suitably grand presentation gift. When it came to a more general clientele, the firm faced stiff competition from the big established Moscow firms like Grachev, Ovchinnikov, Khlebnikov, and Smirnov, and there can have been little incentive to try and compete on a large scale. In the 1899 price-list of Fabergé’s Moscow store, for instance, only two of the 166 items listed for sale are icons.5

In the lives of the imperial family, icons were given and received on all the important occasions of public and private life: christenings, weddings, and anniversaries, to give thanks and to ask for protection and intercession. Two early Fabergé triptychs from the reign of Alexander III show the church’s canonical requirements for producing icons tolerated a very wide stylistic and emotional range, reflecting the cultural dualism that Peter the Great’s reforms had created in Russian society two centuries earlier. A triptych of the Elevation of the True Cross6 made in the workshop of Mikhail Perkhin (active 1860-1903) perhaps commemorated the arrival of the Dowager Empress Maria Fedorovna in Russia in 1896; it was later given by her daughters Grand Duchesses Olga and Xenia to her confessor, Leonid Kolchev (G). With its academic painting and its florid neo-Rococo frame, the triptych radiates the sophisticated Westernized taste associated with the St. Petersburg elite and the higher clergy. From Erik Kollin’s (active 1870-1901) workshop comes a miniature triptych marking the miraculous delivery of the imperial family from a catastrophic train wreck at Borki in 1888 (H). Presented to the Empress Maria Fedorovna by a group of well-wishers, the triptych’s central icon is the so-called Romanov Savior framed by a prayer of thanksgiving, while the Empress’s name saint, Mary Magdalene, and the Guardian Angel are depicted in cloisonné enamel on the wings. Set in a gold outer case adorned with a sunburst and the All-Seeing Eye, the whole triptych is a hybrid of worldly European taste and an Orthodox piety just awakening to the appeal of national traditions.

(Zeisler, Wilfried (ed.), Fabergé Rediscovered, 2018, p. 197)

H. Miniature Triptych with Romanov Savior, Workmaster Erik Kollin (active 1870-1901), Fabergé, St. Petersburg, 1888 (Uppsala Auktionskammare, 17 November 2006, Lot 1162)

Even the most unassuming Fabergé icons, small enough to hold in one’s palm, often have imperial connections, suggesting that the firm’s stores in both Russian capitals were the destination of choice for family members seeking an Easter, Christmas, or name-day gift that could then be personalized with a handwritten inscription on the back. Examples of such gifts include a small icon of the Vladimir Mother of God given by Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna to her son, Prince Nikita, on Easter 1916 (I.); and two pendant icons commissioned by Felix Count Sumarokov Elston, Prince Yusupov for his mistress and the children they had together (J-K).

J. Parcel-gilt Silver Pendant Icon of the Kazan Mother of God, Fabergé, Moscow, 1908-1917. Given by Felix Count Sumarokov Elston, Prince Yusupov to His Son. The wood back is inscribed in ink in Cyrillic: “Elevoery born 6th October 1914, Petrograd.” (Sotheby’s London, 1 December 2010, Lot 647)

K. A Silver and Enamel Personal Icon of a Guardian Angel, Fabergé, Moscow, 1899-1908. Given by Felix Count Sumarokov Elston, Prince Yusupov to one of his children. On the reverse the prayer Spasi i sokhrani in blue champlevé, with engraved Cyrillic inscription “Christmas Eve 1909.” (Sotheby’s New York, 14 October 2015, Lot 157)

Valentin Skurlov’s work in the Fabergé archives has revealed how His Majesty’s Cabinet organized the ritual of official icon gift-giving. Beginning in 1900, the Fabergé firm was tasked with providing oklads for icons intended as christening or wedding gifts for members of the court. Skurlov has identified 18 imperial icons commissioned from the firm between 1900 and 1914. Three batches were painted-by Aleksandr Blaznov (1900), Fedor Platonov (1906-08) and Vasily Gurianov (1907-09)-and sent to Fabergé for mounting in gold or silver-gilt oklads. The approved subject for christening icons and for wedding icons for ladies-in-waiting and women of the imperial family was the Fedorov Mother of God, the Romanov dynasty’s patronal icon, while bridegrooms received the icon of Christ Not Made by Hands.

A further document records how in 1907 Nicholas II gave orders to create a new reserve of less-expensive presentation icons on which to draw as the need arose. Gurianov was chosen to paint prototypes of approved images for weddings and christenings in several sizes. On the appropriate occasion, an icon was sent to Fabergé for mounting in an oklad whose value matched the size of the icon and, presumably, the rank of the recipient. A three-tiered price range was thus established, determined by the size of the icon and the materials used (silver gilt or solid gold, with or without a halo or radiance, embellished with semi-precious stones or gems). While the cost of the painting varied only slightly, between 70 and 125 rubles, Fabergé’s bill could range from 400 rubles for a silver-gilt oklad with enamel and colored stones to a jaw-dropping 6,619 rubles for a gold cover and radiance or halo set with precious stones.

Especially interesting in this document is the Emperor’s instruction regarding the style of these official gifts. Gurianov’s sample icons “in the old style” received imperial approval, and he was ordered to paint a pair for the forthcoming wedding of Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna in 1908. Fabergé’s first designs were rejected, however, and sent back with instructions that “ancient designs be used for the oklads.” This same preference for more obviously “Russian” icons may explain why, in 1911, the firm was ordered to remove from its oklad an icon painted by Platonov four years before and replace it with a new icon of Christ Not Made by Hands, this time painted by Gurianov. In this relatively minor incident we see the interest Nicholas II took in the stylistic nuances of the icons given in his name.

None of these 18 imperial icons appears to have surfaced among the Fabergé pieces known today, but one can form some idea of the Russian aesthetic Nicholas and Alexandra increasingly favored from the pair of wedding icons-of the Iverskaia Mother of God (L.) and Christ Pantocrator (M.) at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. The icons are painted in the 17th century style perfected by Gurianov and other Mstera painters, and are set in oklads whose filigree traceries, threads of seed pearls, and cabochons in toothed cages recall the traditions of icon adornment practiced in the reign of Nicholas’s favorite ancestor, Emperor Alexei Mikhailovich.

M. Icon of Christ Pantocrator, Fabergé, Moscow, 1914-1917. (Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. Bequest of Lillian Thomas Pratt. Photograph by Katherine Wetzel. © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.)

The Fabergé firm served a clientele with quite diverse tastes at a time of extraordinary social unrest and transformation. The firm provided Princess Zinaida Yusupova with a solidly conservative triptych for her friends Prince Mathias and Princess Sophie Cantacuzene on their 25th wedding anniversary in 1913 (N). At the same time, it created a truly modern icon for the 20th century, the triptych given to Colonel Dmitry Loman around 1912 in recognition of his labors overseeing construction of the Fedorov Village complex at Tsarskoe Selo (O).7 Such fascinating contrasts make the question of Fabergé’s icon production ripe for further investigation.

O. Triptych Icon of the Serafimo-Ponetaevskaia Sign Mother of God, Fabergé, St. Petersburg, circa 1912. Icon Signed by N. Emelianov. Close-up of Fabergé Back-stamp on Verso (Jackson’s, 13-14 November 2012, Lot 199)

Dr. Wendy Salmond teaches Art History at Chapman University in Orange, California. Her research interests include all aspects of visual and material culture in late Imperial Russia, but especially the arts and crafts, decorative arts, and icons. She was first introduced to Fabergé while serving as a visiting curator at Hillwood Estate, Museum & Gardens in Washington, DC, in 1995.

| 1 | For a brief introduction to icons, see Wendy R. Salmond, Russian Icons at Hillwood (Washington, DC: Hillwood Museum and Gardens, 1998). On oklads, see Salmond, “The Art of the Oklad,” in The Post, 3(2) (Autumn 1996): 5-16. |

| 2 | Birbaum recalled, “A large part of the production was church silver and icons,” Written in 1919, his memoirs can be found in two publications: The History of the House of Fabergé According to the Recollections of the Senior Master Craftsman of the Firm, Franz P. Birbaum, published by Tatiana F. Fabergé and Valentin V. Skurlov (St. Petersburg, 1992) and Géza von Habsburg and Marina Lopato, Fabergé: Imperial Jeweller (St. Petersburg: State Hermitage Museum, 1993), p. 448. |

| 3 | Valentin Skurlov has been a lone pioneer in the study of Fabergé’s icons. His blog contains much new information on the painters who specialized in icon painting for the firm, as well as archival documentation from His Majesty’s Cabinet. See also Valentin Skurlov and Aleksandr Ivanov, Tserkovnye veshchi – podarki iz Kabineta Ego Velichestsva (1872-1917gg.) (St. Petersburg: Antikvarnoe obozrenie, 2004). |

| 4 | This number comprises icons that can be documented by a photograph; the lack of images in older auction catalogues makes it impossible to identify the icons. Of the 132 icons I have traced, 14 are triptychs, 46 are icons of Christ (including miniatures of the Resurrection), 38 of the Mother of God, and 34 of various saints and the Guardian Angel. |

| 5 | K. Faberzhe, pridvornyi postavshchik. Zolotye, brilliantovye i serebrianye izdeliia (Preiskurant izdelii Mosk. Otd-niia firmy Faberzhe, 1899 g.) (Moscow: Zhurnal ‘Russkii iuvelir’, n.d.). |

| 6 | Korneva, Galina, and Tatiana Cheboksarova, “Elevation of the True Cross Icon”, in Wilfried Zeisler (ed.), Fabergé Rediscovered, 2018, pp. 196-99. |

| 7 | (Ed. note: Detailed research on the icon by Wendy Salmon.) |

If there is one item synonymous with the grandeur of the Russian empire, it’s “Fabergé.” It is hardly a coincidence that Fabergé-referring to luxury jewelry and imperial Easter eggs and the accompanying symbolic cultural capital-has figured prominently in the ongoing project in post-Soviet society of the restoration of knowledge of the vanished culture of the imperial period. After decades of silence and neglect in the Soviet Union, the Fabergé eggs have come to signify Russia’s magnificent heritage internationally, a distinction both obvious and strange, since Fabergé had never been nominated to fulfill such a lofty duty during the imperial era.

The Fabergé Museum opened in St. Petersburg in November 2013 in the newly restored Shuvalov Palace. One of the most recent private cultural undertakings, this collection is devoted to the works of the famous Carl Fabergé, jeweler of the Russian emperors. It was created by The Link of Times Foundation, which one of Russia’s richest men, metals and oil magnate Viktor Vekselberg, established with the express purpose of repatriating prominent items of the imperial heritage to Russia. In 2004, Vekselberg acquired Malcolm Forbes’s collection of Fabergé’s works, which included nine imperial eggs. Since then, the collection has grown to 4,000 decorative and fine-arts items and has become a major tourist attraction. It is appropriate to expect the rhetoric of national pride to become attached to the return of famous artifacts to their homeland, but somber celebratory rhetoric has yet to materialize. Paradoxically, Fabergé in today’s Russia is indeed a recognizable and marketable symbol, but a symbol from which generations of Soviet citizens have been estranged. The Fabergé eggs represent a peculiar restoration: a nostalgia for the severed imperial past, banned for most of the 20th century, and a national cultural heritage that had attained value beyond Russian borders. In the new context in post-Soviet Russia, suspended outside of history in the protective glass cases in the new Fabergé Museum, the much coveted, genuine Fabergé eggs seem, paradoxically, to lack authenticity.

For the invented tradition of the Fabergé Eggs to take root in the popular imagination as a source of pride and a symbol of identity, a different narrative is needed, which has yet to be written. If the history of the reception of sensational art acquisitions in Russia is any indication, there are grounds for optimism this revised story will emerge in due course. The serious scholarly and populist work the new Fabergé Museum in St. Petersburg has been doing will no doubt contribute to this emergent narrative of the Russian art empire’s remarkable revival. This museum is key in the Russian scenario of recent repatriations; it authenticates and could conceivably correct public criticism of extravagant donations. Within the walls of the Fabergé Museum, the repatriated international sensations are well positioned to turn someday from a pricey commodity into perhaps indeed an integral part of the Russian national heritage.

Dr. Ekaterina “Katia” Dianina is an associate professor of Slavic languages and literatures at the University of Virginia. Her publications have appeared in the Slavic Review, The Russian Review, SEEJ, and Journal of European Studies, among others. Her first book, “When Art Makes News: Writing Culture and Identity in Imperial Russia, 2013″, was awarded the AATSEEL Prize for the Best Book in Literary and Cultural Studies. An expanded version of this essay will be published in Gahtan, M., and, E.M. Troelenberg (eds.), Collecting and Empires: The Impact of Empires on Collections and Museums from Antiquity to the Present, 2019.

Christel McCanless: When Emmanuel Ryz, Fabergé enthusiast from Paris, France, registered for the Fabergé Gathering in Richmond, I knew the participants were in for a special treat. With a bit of gentle persuasion, he agreed to showcase his short video as the finale for the event. How did he become interested in Fabergé?

He writes: “At the age of 13 in 1983, I was in London visiting the Crown Jewels installed at the Tower of London. There, in the midst of the scepters and crowns, I came face to face with the three Imperial Eggs belonging to the Queen of England. It was the beginning of a passion that has lasted until today and it does not fade, quite the contrary.

Ten years later the idea of making a documentary film began to germinate. Finally, in 2001, I was able to travel and see not only Imperial eggs in different museums (New Orleans, New York, Baltimore, Washington), but also to meet specialists who are in direct contact with the Imperial Eggs. Up to that time I had only known them through books. Attending auctions of Imperial eggs in New York and London followed. Gradually my passion and my enthusiasm opened the world of Fabergé to me, and I became a part of it. I was allowed to film two of the surviving Imperial Eggs (1906 Swan and 1908 Peacock in the Sandoz Collection, Switzerland), showing the beauty of those eggs and hoping to convince other owners to allow me to film their eggs. The film is the beginning of my quest not only to show most of the eggs that have survived but also hopefully to find more information regarding – or images of – the seven missing eggs in time for the 2020 centenary celebration of the death of Carl Fabergé. I am currently discussing financing with possible sponsors for my filming, with the goal of showing films of the eggs worldwide.” Contact: Emmanuel Ryz

Wilfried Zeisler, chief curator at Hillwood Estate, Museum & Gardens in Washington (DC), presented a PowerPoint talk, From Empress Maria Feodorovna’s Blue Study to Marjorie Post’s French Drawing Room: Stories behind Hillwood’s Table Clock, at the Fabergé Gathering in Richmond, Virginia, on July 27, 2018. The next day, 35 Fabergé enthusiasts traveled in carpools to Washington and we began our day at the museum with an enlightening Fabergé venue tour by Zeisler, our host.

Hillwood Exhibition Highlights:

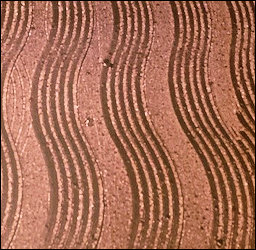

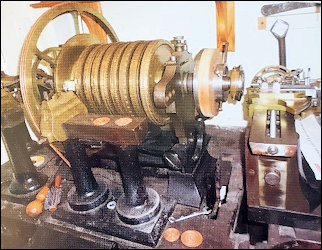

- Discovering Guilloché: A process of incising thin, shallow, faceted lines onto a metal surface using a hand-operated lathe called a rose engine or straight-line guilloché machine.

Oval Dish from the Henrik Wigström Atelier and Enlarged View of a Guilloché Application

Oval Dish from the Henrik Wigström Atelier and Enlarged View of a Guilloché Application

(Photographs by Christel McCanless) Bower Rose Engine with a Geometric Apparatus behind the

Bower Rose Engine with a Geometric Apparatus behind the

Headstock, the Mechanism Creating the Incised Lines

(Courtesy of David Wood-Heath, UK) - Objects with a Red Cross Theme: How Do They Connect? Research in Progress.

Fabergé Silver Red Cross Box, Widow’s

Fabergé Silver Red Cross Box, Widow’s

Workmaster Mark Anna Ringe (Active 1912-17),

St. Petersburg. Inscribed M.V. Shteiger,

November 10, 1916.1

(Courtesy McFerrin Collection) Cigarette Case, Workmaster R.D., 1914-17, Moscow

Cigarette Case, Workmaster R.D., 1914-17, Moscow

(Hillwood Collection) First Aid, Russian Postcard with Image of

First Aid, Russian Postcard with Image of

Wounded Soldier Designed by S. Yaguzhinsky, 1911

(Shared by Wilfried Zeisler from a Facebook Search) - Fabergé Eggs Galore on View

1895 Blue Serpent Clock Egg

1895 Blue Serpent Clock Egg

(Collection of Prince

Albert II of Monaco) 1907 Youssoupov Egg

1907 Youssoupov Egg

(Fondation Edouard

et Maurice Sandoz

Collection, Switzerland) 1896 Alexander III Portraits Egg (aka Twelve Monograms Egg) with

1896 Alexander III Portraits Egg (aka Twelve Monograms Egg) with

Modern Stand and 1914 Catherine the Great Egg with 1945

Stand Made at the Request of Mrs. Marjorie Merriweather Post

(Photograph by Alex Braun, Courtesy Hillwood Collection)

Hillwood sponsored a Fabergé Rediscovered lecture series during the Fall of 2018:

The Firm of Fabergé: Business, Clients, and Collectors

Wilfried Zeisler, Hillwood’s chief curator, explored the history of the firm of Fabergé and the success of its creations among Russian imperial clientele and later American collectors such as Marjorie Merriweather Post.

Russia, Royalty and the Romanovs

Caroline de Guitaut, senior curator of decorative arts at the Royal Collection Trust, examined the relationship between Britain and Russia using Fabergé artworks drawn exclusively from the Royal Collection. The book, Russia: Art, Royalty and the Romanovs by Caroline de Guitaut and Stephen Patterson, accompanying the Russia, Royalty & the Romanovs exhibit at the Queen’s Gallery, London, has been published.

Just announced on the Royal Collection website is a series called Trail: Fabergé in the Royal Collection supplementing the above exhibition closing on April 28, 2019.

Fabergé in London

Kieran McCarthy, an expert on the work of Russian Imperial jeweler Carl Fabergé, presented an illustrated lecture about the glittering history of Fabergé’s British branch, from its opening in 1903 to its closure in 1917.

Readers shared two links after viewing the McCarthy lecture – one contains an online visit to the new Wartski London retail shop and the other shows the discovery of a new Fabergé hallmark.

| 1 | McCanless, Christel L. and Daniel Brière, “The Russian Red Cross and Imperial Patronage” in McFerrin, Dorothy, From a Snowflake to an Iceberg, 2013, pp. 152-53. |

Wilfried Zeisler’s introduction sets the stage for Hillwood’s Fabergé Rediscovered exhibition by describing the background on a leading American socialite and the heiress of General Foods, Inc. Marjorie Merriweather Post was one of the earliest collectors of Fabergé among other wealthy American women connoisseurs in the 1930s and 1940s, who also included Lillian Thomas Pratt in Richmond, Virginia, Matilda Geddings Gray in New Orleans, Louisiana, and India Minshall in Cleveland, Ohio. Zeisler discusses some of the earliest publications by Henry C. Bainbridge (1846-1920), manager of Fabergé’s London branch (1905-1915), who inspired Mrs. Post’s collecting interests.

In the chapter entitled, “Carl Fabergé, a Nineteenth-century Jeweler and Businessman,” Zeisler opens with a brief history of the Fabergé family and the training Gustav Fabergé, Carl’s father, received under Andreas Spiegel and the famous jeweler Keibel before opening his own shop in St. Petersburg, Russia. Carl Fabergé’s training in Europe and his travels are explored, showing the influence of 18th century gold-work collections on the young jewelry student. An egg-shaped box from the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen in Dresden, Germany, is illustrated which possibly was the inspiration for Fabergé’s 1894 Renaissance Egg. Not only was the young Fabergé inspired by 18th century gold work in the Hermitage, where he volunteered to repair pieces, but he also was interested in ancient gold work. A gold bracelet by Fabergé workmaster Erik Kollin (1870-1889) from the McFerrin Collection in Houston shows the virtuosity of the Fabergé firm.

In the same chapter Zeisler explores the multiple international exhibitions that spread the fame of the Fabergé firm. Included are two exquisitely detailed photographs (figs. 14 and 19) of the 1896 Twelve Monograms Egg, acquired in 1949 by Mrs. Post for $1,739.13. This egg has had several names over the years, including Twelve Panel Egg and Twelve Monograms Egg. It is now identified correctly based on the description from the original Fabergé invoice as the 1896 Alexander III Portraits Egg and in 2008 was placed by Fabergé egg historian Annemiek Wintraecken into the proper timeline of Imperial eggs made by Fabergé. (“The Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs: New Discoveries Revise Timeline,” Fabergé Research Newsletter, November 2008.) The 1887 Third Imperial Easter Egg is illustrated twice in the catalog (figs. 13 and 130), and Zeisler mentions the importance of its 2014 re-discovery to the re-dating of the 1896 Twelve Monograms Egg (1896 Alexander III Portraits Egg). Wintraecken’s webpage on this egg summarizes the egg’s long history. Once the Third Egg was found, the Hillwood egg fit perfectly into the 1887 slot of Wintraecken’s revised timeline list.

Another discovery concerning Hillwood’s 1896 egg was revealed in 2013 by Anna and Vincent Palmade, who identified the 1887 Third Imperial Egg from an old 1964 Park Bernet auction catalog. In the Fabergé Research Newsletter, Winter 14, their discovery of the “1896 Alexander III Portraits Egg – Missing Surprise Identified in Photographs” is explained. While combing old auction catalogs, they found a folding frame with ten sapphires in a 1961 Christie’s catalog that matched the description of the surprise for the 1896 Alexander III Portraits Egg (or Twelve Monograms Egg) in the original Fabergé invoice. Furthermore, making a Lego-blocks replica of the surprise they found it fit perfectly in the egg. Last seen at auction in 1980, the whereabouts of the surprise are unknown, yet the Palmades hope their article in the Hillwood catalog, entitled “The Twelve Monograms Egg’s Missing Surprise Identified,” will be seen by the current owner and the surprise ultimately reunited with the 1896 egg at Hillwood.

Jennifer Levy’s interesting essay on miniature portraiture and photography in Fabergé’s work explores the relationship between these two art forms in the late 19th to early 20th centuries. Using two Fabergé miniature paintings from the Hillwood collection and the corresponding photographs inspiring them, she makes a strong point concerning the influence of photography on miniature paintings. She suggests rather than killing off painting, photography helped revive miniature painting. Artists had an exact rendering of their subject that allowed them to work from photographs, without requiring the model to sit for long sessions with the artist.

The foremost authority on the Russian Imperial Award system, Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm, explores Empress Alexandra’s presentation snuffbox in the Hillwood collection. She states snuffboxes decorated with miniature portraits (for the most important recipients), diamond cyphers, and enamel and precious stones without imperial cyphers, were “the epitome of monarchial gifts.” She adds, “Altogether, nine snuffboxes were made to be set with portrait miniatures of the empress. Only one of these was presented.” Illustrated are two snuffboxes, one with the cypher of Emperor Nicholas II from the McFerrin Collection in Houston, and one from the Hillwood Collection with a diamond cypher of Empress Alexandra. Both snuffboxes were created by the workmaster Carl Blank from the Carl Hahn firm, a contemporary of the Russian Fabergé firm.

Galina Korneva and Tatiana Cheboksarova contribute the history of the Elevation of the True Cross, a triptych icon by Fabergé at Hillwood. In 1968, Mrs. Post purchased this masterpiece by Mikhail Perkhin (1889-1903) from Wartski’s in London. The authors study the Imperial archives (RGIA) in St. Petersburg, Russia, and in their research, they uncovered the story of this important Imperial icon. They explain the iconography of the paintings, and discuss the markings and writing on the icon linking it to Empress Maria Feodorovna and her confessor Leonid Kolchev (1871-1944). The essay is accompanied is by a full-page photograph of the triptych and its details.

The chapters on Fabergé’s business and clientele give a broader view of the Fabergé firm as a business at the turn of the century. The chapter on Marjorie Merriweather Post, a post-revolutionary Russian art collector with a keen eye, shows her as Malcolm Forbes once described her – a “pioneer” of Fabergé collecting. Each chapter of this book is illustrated with many photographs taken just for this publication by Alex Braun and Bruce White. An appendix at the end of the exhibition catalog includes a directory of workmasters, designers, and other Russian firms working at the time of Fabergé’s, providing another great resource for scholars and beginning enthusiasts alike.