Four Fabergé museum collections exist in St. Petersburg and nearby …

- Hermitage Museum, the world’s largest museum with the addition of the General Staff Building, is being renovated at present

- “The Link of Times” Collection is opening in the restored Shuvalov Palace

- Fabergé objects at Pavlovsk Palace

- Fabergé exhibition at Peterhof Palaces

Readers interested in attending (dates as yet unknown) are asked to share an email address to receive further details as they become available. Your suggestions are welcomed!

While producing over 200,000 individual works of art, pride of place evidently goes to the unique series of 50 Easter eggs, which, after tentative beginnings, culminate in such incredible inventions as the 1914 Grisaille Egg. The gift prompted the Dowager Empress Marie Feodorovna in a letter to her sister, Queen Alexandra of England, to name Fabergé the “greatest jeweler of our time”. Two other unique Fabergé creations are the brilliantly crafted 1914 Mosaic Egg and the magical 1913 Winter Egg, the latter in my opinion Fabergé’s absolute masterpiece.

1885 First Hen Egg

(Courtesy “The Link of Times” Collection)

Saxon Royal Egg, Collection of Augustus the Strong (1670-1733)

(Courtesy Géza von Habsburg)

With help of Dresden scholars the egg (Inv. Nr. VI.XIII) was discovered in the 1921 Dresden Green Vault Museum (Grüne Gewölbe) catalog and described as: The Golden Egg from the property of Augustus the Strong. After unscrewing the cover, the golden yolk can be removed, underneath sits a broody hen with ruby eyes. This hen can be opened and contains a diamond-set royal crown set beneath with a carnelian matrix engraved with a ship in a stormy sea inscribed “Constant malgré l’orage”. The crown can be opened and two of its ribs hold a ring with diamonds surrounding a table-cut diamond.

A very similar egg (below) is preserved in the Danish Royal Collections in the Amalienborg Museum, Copenhagen; which has hitherto been considered as the prototype for Fabergé’s 1885 Hen Egg. Another, also very similar, formerly owned by the Habsburg Imperial Family, is in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

18th Century Easter Egg, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

(von Habsburg, Fabergé, 1987, 315-6)

1894 Renaissance Egg – 18th Century Casket by LeRoy by Dr. Géza von Habsburg

Numerous links tie Carl Fabergé to the Green Vault Museum in Dresden, Germany. Fabergé’s parents resided in Dresden from 1860 until their death in 1894 and 1903, respectively. Fabergé spent formative years in the Saxon capital, and his brother Agathon was born there in 1862. Young and impressionable Fabergé was evidently overwhelmed by the riches of the royal museum and in particular, its hardstone and enameled gold objects. In 1953, A. Kenneth Snowman of Wartski made the first connection between the 1894 Renaissance Egg with an 18th century casket by LeRoy in the Green Vault. Tell-tale photographs of the two eggs side by side, both open and shut were taken by the author at the occasion of the 1986 Munich exhibition. They seem to demonstrate that Fabergé is likely to have held the casket in his hands.

LEFT EGG: 18th Century Casket by LeRoy | RIGHT EGG:Fabergé 1894 Renaissance Egg, “The Link of Times” Collection

(LEFT PICTURE: Photograph © Géza von Habsburg | RIGHT PICTURE: Courtesy Green Vault)

Additional links connect Carl Fabergé to the works of the great Dresden goldsmith Johann Melchior Dinglinger (1664-1731), so clearly the Russian master’s spiritual forefather. His works are present not only in Dresden Green Vault, but also in the treasury of the State Hermitage Museum, easily accessible to Fabergé as of the 1860s.

1895 Blue Serpent Egg Clock – Predecessors Galore! by Annemiek Wintraecken

1895 Fabergé Blue Serpent Egg Clock

(Courtesy Prince Albert III of

Monaco Collection)

The 1895 Egg Clock has some remarkable predecessors. See for yourself, which one you would chose as a possible prototype.

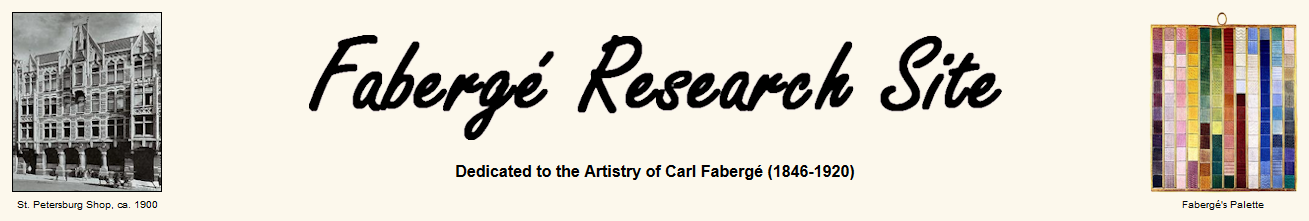

1903 Peter the Great Egg

Dr. Géza von Habsburg identified an 18th century Nécessaire Egg in the State Hermitage Collection as the predecessor of the 1903 Peter the Great Egg.

1903 Peter the Great Egg

(Courtesy Virginia Museum of Fine Arts)

18th Century Nécessaire Egg with Clock and Travel Kit

(Courtesy State Hermitage Collection)

1906 Swan Egg

Video about the restoration and conservation by the Bowes Museum (Barnard Castle, Co. Durham, England) of the silver swan in the 1906 Swan Egg (Fabergé Research Newsletter, Fall 2012, Courtesy of Juan F. Déniz)

1906 Swan Egg

(Courtesy Sandoz Foundation Collection)

1773 Silver Swan by James Cox

(Courtesy Bowes Museum)

1908 Peacock Egg

The essay, Fabergé and Roullet et Decamps Walking Peacocks: More Than Just a Coincidence? by Juan F. Déniz, in the Fabergé Research Newsletter, Fall 2012, discusses peacock predecessors.

1908 Peacock Egg

(Courtesy Sandoz Foundation Collection)

1780 Peacock Clock by James Cox

(Courtesy State Hermitage Collection)

(Courtesy State Hermitage Collection | Hosted by YouTube)

1910 Alexander III Equestrian Egg

Kremlin Collection

(Courtesy Wiki)

Reliquary of St. Ranieri

(Courtesy Museum of Silver

in Florence, Italy)

Detail of the 1910 Alexander III Equestrian Egg

(Courtesy Kremlin Collection)

Detail of the Reliquary

(Courtesy Museum of Silver in Florence, Italy)

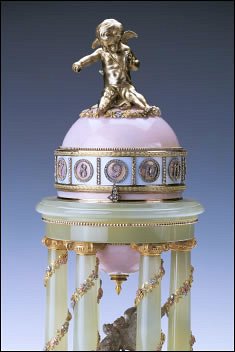

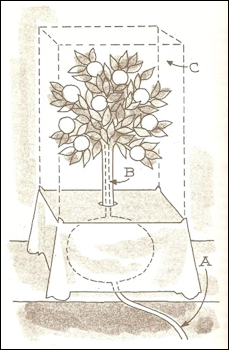

1911 Bay Tree Egg

(Courtesy “The Link of Times” Collection)

Richard of Paris Automaton

(Sotheby Parke Bernet,

Mentmore Auction, 1977)

These tubs as they are often labeled in descriptions of the objects d’art they inspired, also facilitated the king’s use of these orange trees to decorate the Hall of Mirrors on special occasions. His design endures in both art and present day gardens and remains in production today in Versailles by the firm Orange Tree Planters, Paris. On the final weekend of September 2013, I watched gardeners in both the Catherine Park at Tsarskoye Selo and the Peterhof Gardens loading these Versailles planters (with their topiary trees) onto trailers to be taken inside for the winter months.

Ornamental trees with fruit were not the only common factor French noble tastes shared with the 1911 Imperial Egg and its mechanical singing bird. One did not have to be royalty to keep canaries in France in the 18th century – they were luxury items. They had to be imported from the Canary Islands, as their name suggests. The species had the ability to learn a variety of songs.

In 1746, several automaton flute players and mechanical birds were exhibited at the Tuileries. It was not long before various master craftsmen, applied their ingenuity, noting that Black Forest craftsmen had been building cuckoo clocks since the 1730s. These atelier establishments constructed hundreds of singing birds, popping up out of clocks, snuffboxes, and decanters. “The actual singing mechanism of these artificial singing birds was located elsewhere in the piece, usually it was hidden within a compartment in the snuffbox or decanter or clock separate.”2

Among a growing cadre of Court ‘Mechanicians’, Robert Richard appeared in Paris around 1770 with an ensemble of automaton musicians. In 1757, a delicate and finely crafted musical automaton appears, attributed to none other than Richard of Paris. Billed as the greatest auction since the French revolutionaries sold off Versailles3, the Mentmore auction4 as Lot 49 offered: “An Extremely Rare Louis XV Singing Bird and Orange Tree Musical Automaton by Richard of Paris. The movement is signed Richard Rue des provaires á Paris and dated 1757”. The metal tree was enameled in natural colors with green leaves and gold oranges enlivened by white Vincennes porcelain orange blossoms. The two birds, probably re-feathered later, perched amid the branches, while the movement and a small pipe organ were contained in a square kingwood and tulipwood parquetry tub with trellis work panels on each side. As the gavel fell, it was a London dealer who paid $153,000 for the 200-year old enamel orange tree automaton with singing birds.5

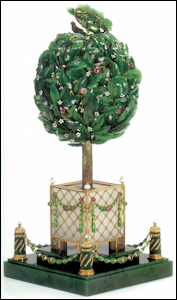

A little over a half century later, the concept of the animated Orange Tree was addressed by Jean Eugène Robert-Houdin, the son of a French clockmaker, born in 1805 in Blois, France. Elaborate mechanical toys operated by clockworks, so called ‘automata’ were very popular in France when he presented his works at the Exhibition of the Société des Artistes Indépendants held in Paris in the summer of 1844.

Robert-Houdin and His Orange Tree Trick

(Sources: Harry Houdini6 and Edwards7)

The more familiar magician Harry Houdini (1874-1926) adopted his stage name in honor of his predecessor, and actually paid a visit to Moscow and the infamous Butyraskaya Prison in 1908, performing a dramatic escape for the prisoners. Built during the reign of Catherine the Great, the prison housed former nobles, enemies of the revolution and future rebels including Alexander Solzhenitsyn.8

At the end of the 19th century the advent of the Art Nouveau style in Europe proved fertile ground for the ‘Orange Tree’ motif. A monumental version is The Secession Building, designed by Joseph Maria Olbrich and built in Vienna 1898. It was on a visit to Vienna over a decade ago when I began to consider it as a possible stylistic inspiration for the 1911 Bay Tree Egg along with its even stranger bedfellow, the illusional automatons developed in France by Robert-Houdin. I appreciate the earlier commentary on this comparative by Géza von Habsburg, as well as a photo of the Richard of Paris Orange Tree published by Hermione Waterfield and Christopher Forbes.9 The building was to become a key work of Viennese Art Nouveau. Its laurel (or bay) leaf dome hovers over the building in the form of 3000 gilt leaves and 700 berries. The foliated dome was nicknamed the ‘golden cabbage’ by contemporaries.”

Secession Building in Vienna

(Left Image and Larger Views are Courtesy of Several Secession Building Websites | Right Image is Courtesy of Géza von Habsburg)

Den in the Villa Hvidøre

(Korneva and Cheboksarova10)

Collectively speaking, the inspiration of these historical antecedents cannot be understated. Fabergé’s Bay Tree, clearly has deep artistic as well as cultural roots. Certainly, the influence of the Louis XV Singing Bird and Orange Tree Musical Automaton and more broadly Robert-Houdin’s Orange Tree Trick is well-defined:

- The use of the distinctive design of the topiary orange trees. Both objects incorporate as their tub, the historical Versailles Orange Tree planter (still in situ, and produced by a firm in Paris today), and a common base with elements including the delicate trellis design on the sides of the planter.

- The camouflage technique in placing the key/hole amid the finely carved nephrite/green enameled leaves.

- The white Vincennes porcelain orange blossoms of the Parisian automaton and its beneficiary’s ‘flowers enameled white and set with diamonds’.

- The ‘feathered’ song birds emerging from the tree top, with the mechanism concealed in the base, elements shared as well with Robert-Houdin’s more primitive Orange Tree Trick.

Antecedents of the 1911 Bay Tree Egg reflect both function (the automata) as well as stylistic design. To close this examination, I propose two design examples: a jetton struck at the end of the 17th century, and a Fabergé brooch possibly predating the 1911 Tree.

Louis XIV Brass Jetton with Orange Tree

17th Century Propaganda Piece

(Author’s Collection)

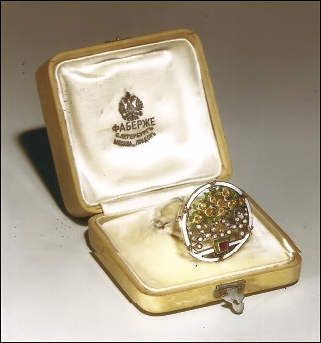

Fabergé Brooch with Flowering Tree Growing in Tub

(Snowman, Fabergé: Lost and Found, 1993, 52-3)

1 Fabergé, Tatiana, et al. The Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs, 1997, 248.

2 Metzner, Paul. Crescendo of the Virtuoso: Spectacle, Skill, and Self-Promotion in Paris During the Age of Revolution, 1998, 174.

3 Eugene Register Guard, May 18, 1977.

4 Sotheby Parke Bernet, Mentmore, Volume 1: Furniture, May 18-20, 1977, p. xiii & 44-45. Special thanks to Lois White, Getty Museum Library.

5 Daytona Beach Morning Journal, May 19, 1977.

6 Houdini, Harry. The Unmasking of Robert-Houdin, 1908, 51.

7 Edwards, I.G. The Magic Man, 1908, 159.

8 Smith, Douglas. Former People: The Final Days of the Russian Aristocracy, 2012, 248.

9 von Habsburg, Géza. Fabergé Imperial Craftsman & His World, 2000, 222; Waterfield, Hermione & Forbes, Christopher. Fabergé: Imperial Eggs and Other Fantasies, 1978, 138.

10 Korneva, Galina and Cheboksarova, Tatiana. Russia and Europe, 2012, 269.

11 von Habsburg, Géza. Fabergé Treasures of Imperial Russia, 2005, 216.

1917 Design Sketch, Blue Tsesarevich Constellation Egg

(Courtesy Tatiana Fabergé)

1917 Blue Tsesarevich Constellation Egg

(Courtesy Fersman Mineralogical Museum, Moscow)

Singer Building Cupola, St. Petersburg, Russia

(Courtesy Valentin Skurlov)

Clock by Etienne Martincourt

(Courtesy Wallace Collection, London)

In 2008, Kieran McCarthy suggested a clock from the Wallace Collection in London as a prototype. (Fabergé Research Newsletter, January 2008)

In 2013, the unfinished Tsevarevich Blue Constellation Egg is sometimes displayed with a gold band (illustrated above) or a Lucite band between the constellation halves to support its delicate nature. The egg with the Lucite band is shown next to a “finished” egg from the Fabergé Museum in Baden-Baden, Germany. (Royal Russia, February 8, 2013)

Russian Imperial Treasure

Kamer-Kazak Kudinov (1878-1915)

Pavlovsk State Museum Collection

(Skurlov, Fabergé, T. and Ilyukhin, Fabergé

and His Followers, Hardstone Figures, 2009, 62)

Kamer-Kazak Pustynnikov (1857-1918)

(Photographs by Walter Hill and

Courtesy Stair Galleries, Hudson, New York)

Marks on Kamer-Kazak Pustynnikov’s Boots Used in Authentication

(Photographs by Walter Hill and

Courtesy Stair Galleries, Hudson, New York)

The companion piece (left), also commissioned by Emperor Nicholas II in 1912, is a figure of Alexei Alexeievich Kudinov (1878-1915), Kamer-Kazak of the Dowager Empress Marie Feodorovna in the Pavlovsk Palace State Museum near St. Petersburg, Russia.

October 29, 2013 Sotheby’s New York

Important Silver, Vertu, and Russian Works of Art

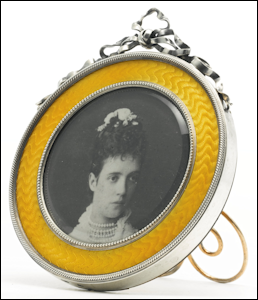

Photograph Frame by Andrei Gurianov, St. Petersburg, 1908-1917

(Courtesy Sotheby’s New York)

Important Russian Art

Elephants from the Estate of H.R.H. The Prince Henry,

Duke of Gloucester

(Courtesy Christie’s London)

Fan with Fabergé Guard, Mikhail Perkhin, 1899-1904

(Courtesy Christie’s London)

Russian Auction

Tercentenary Anniversary Jewelry

(Courtesy Bonhams London; Nagel Auktionen, Stuttgart, Germany)

The Bonhams’ pendant with a necklace was acquired by the Cabinet of His Imperial Majesty from Fabergé’s St. Petersburg branch on 28 February 1913 for 90 rubles.

The brooch in the Nagel Auktionen Stuttgart (October 9-10, 2013) did not sell.

[More information: Celebrating the Romanov Tercentenary with Fabergé Imperial Presentation Pieces: A Review by Roy Tomlin]

November 27, 2013 MacDougall’s London

Works of Art

Bell Push by Julius Rappoport, 1899-1903

(Courtesy MacDougall’s London)

(Updates are posted in Exhibitions on the Fabergé Research Site)

July 8, 2013 International Museum of the Horse, Lexington, Kentucky

Opening of a semi-permanent exhibition honoring Frank Caton (1852-1926) as a new “Immortal” inductee into the Harness Racing Museum and Hall of Fame. A highlight in the “Frank Caton and Russian Harness Racing” exhibit is an octagonal presentation tray by Fabergé with eight ovals engraved with the names of 43 Russian donors.

Danish Royal 50th Wedding Anniversary Kovsh

(von Habsburg and Lopato, Fabergé: Imperial Jeweller, 1993, 234-35)

Denmark and the Tsars in Russia, 1600-1900

Venue includes the Golden Wedding Anniversary wine cooler (32.4″ | 82.2 cm long) created by Fabergé as a gift from Tsar Alexander III and his wife Maria Feodorovna to her parents, King Christian IX and Queen Louise of Denmark, and a necklace of pendant eggs also by Fabergé.

Chased Red Cross Box, Workshop of Anna Ringe before 1912, 2” in Diameter

(Courtesy The McFerrin Collection)

The Artie and Dorothy McFerrin Collection has quickly become one of the world’s most significant private Fabergé collections. Exquisite photography supplemented with auction catalog descriptions and interesting reflections by Dorothy McFerrin chronicle Fabergé’s masterworks along with the Romanov family and other patrons of the House of Fabergé. A plethora of research essays for the book highlighting unique aspects of the collection were contributed by Timothy Adams, John Atzbach, Daniel Brière, Tatiana Fabergé, Alice Milica Ilich, Christel Ludewig McCanless, Dorothy McFerrin, Dr. Mark A. Schaffer, Peter L. Schaffer, Matthew Stuart-Lyon, Dr. Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm, Dr. Géza von Habsburg, and Annemiek Wintraecken. Proceeds from the publication will benefit the Houston Museum of Natural Science in Texas where the collection is on view for an indefinite time.

Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm, Annemiek Wintraecken, and Christel McCanless

at 24 Bolshaya Morskaya, St.Petersburg, Russia