with Research Contributions from Fabergé Enthusiasts Worldwide

- “Authenticity is the soul of the object. Anything that is worth something is worth being faked.”

Nicolas Chow, Sotheby’s Chinese Works of Art Expert - “Every object has a story worth telling, worth finding.”

Jerry’s Vintage Treasures LLC - “…Expanding scholarship leads to the reassessment of objects that once passed muster without question.”

David Park Curry, Fabergé: Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, 1995, p. 103. - “Spend energy learning about the real thing.”

Silver Forums

The Jury of Class 95 (Joaillerie et Bijouterie) analyzed Fabergé’s exhibits as follows:

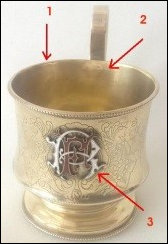

![Finger Bath with Hallmarks by Henrik Wigström (1862-1930 [sic]), Died in 1923, Offered at a French Auction. The color combination is not likely to have been used by the Faberge firm.](https://fabergeresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/2017fallandwinternl2.jpg)

Finger Bath with Hallmarks by Henrik Wigström

(1862-1930 [sic]), Died in 1923, Offered at a

French Auction. The color combination is not

likely to have been used by the Fabergé

firm for a stamp moistener.

Fauxbergé or Fabergé?

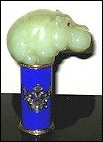

“NOT!” squawks Fabergé Russian Hornbill to the

imposter Goose now thought to be German.

(Curry, Fabergé: Virginia Museum of Fine

Arts, 1995, pp.102-103)

Hornbill later attributed to Cartier.

(von Habsburg, Fabergé Revealed, 2011, p. 352)

One Hundred Mainly Fauxbergé’s Advertised

as “Karl Fabergé Art Masterpieces

World’s Finest & Largest Private Collection”

(Image Courtesy Géza von Habsburg)

- Objects embellished, through re-enameling, re-gilding, re-decoration with precious stones or re-marking with lacking punches.

- Genuine objects made by Russian contemporaries of Fabergé…turned into Fabergé’s by subsequent marking…

- Complete forgeries, almost without exception bearing the Fabergé signature…appeared after the publication of Snowman’s book, from 1953 onwards…

- Fabergé would never have finished the rim like this.

- Fabergé would have never soldered the handle like this.

- The monogram and engraving are another matter; engraving is not excellent and a piece of enamel was needed to make it ‘Fabergé’. Most probably taken from some lapel badge…and soft soldered (tin) to the body, covering the engraving by the way. Fabergé would probably have it made in champlevé enamel, if the owner had insisted on a monogram…the enamel is of poor quality. If we had it in our hands, we would most probably see more inconsistencies. It was a nice, common piece of silver, I doubt it was completely newly-made – too demanding task – easier to ruin what was at hand.”

Category C. An example of “Complete forgeries, almost without exception bearing the Fabergé signature; some might as well have been produced before the Second World War, the greater part, however, appeared after the publication of Snowman’s book4, from 1953 onwards” was found by dedicated independent researchers DeeAnn Hoff and Kristin Mills at the Maryhill Museum of Art, Goldendale, Washington. The findings are detailed in Case Study V. in the Museums section of this newsletter.

2 Géza von Habsburg, “Fabergé and the Paris 1900 Exposition Universelle” in Habsburg/Lopato, Fabergé: Imperial Jeweller, 1993, p. 121; Synopsis for two 1900 journal articles in McCanless, Christel Ludewig, Fabergé and His Works: An Annotated Bibliography of the First Century of His Art, 1994, p. 25.

3 Fabergé, Court Jeweler to the Tsars, 1979, pp. 149-150.

4 Snowman, A. Kenneth. The Art of Carl Fabergé, 1953. Author, chairman of the British jewelry dealer Wartski, arranged the first Fabergé loan exhibition in 1949. In his book he details the history of the firm and provides technical descriptions of the objets de vertu. A revised and enlarged edition with new information was published in 1962. All subsequent editions and impressions are reprints of this edition.

The problem is that the House of Fabergé was a vast conglomerate, even by today’s standards, employing hundreds of people in five different branches (St. Petersburg, Moscow, Kiev, Odessa and a sales only branch in London), acquiring work from external workshops and, on occasion, even retailing the work of opposition houses. While general guidelines are available to the marking of Fabergé items, there are always exceptions to these rules, brought about by a series of situations, and occasionally by simple, human failings.

Fabergé had to balance two conflicting forces: the standard of workmanship and the pressure to produce. The demand for Fabergé objects was such that overtime was almost constantly worked, and the pressure for completed items seldom waned. But Fabergé would not compromise on quality and one employee, Andrei Plotnitski, has left a graphic account of what happened to objects which were not up to the master’s exacting standards: a hammer literally came down on an item that failed to please and the worker was told to start again. There is some evidence that Plotnitski may have embroidered these recollections and while these memories are interesting, they should be treated with some skepticism.

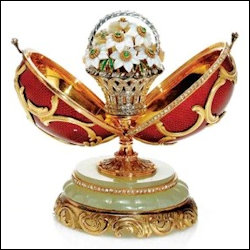

Nevertheless, with such pressures in place, some items made it through to the front counters for sale without marks of any kind. Workmasters simply failed to stamp these items. There are at least three Tsar Imperial Easter eggs in this category. The very first Hen Egg of 1885, the 1901 Flower Basket Egg, and the 1910 Alexander III Equestrian Egg appear to have no marks at all, yet they are unquestionably Fabergé’s work. Some items simply could not be marked: the animal and bird figures fashioned from hardstone, for example. If gold feet were added by the Fabergé firm, they were marked. Evidence suggests that efforts were made most of the time to stamp the flower studies from Henrik Wigström’s workshop but again, examples have been identified where this did not happen. Platinum items (including the 1910 Alexander III Equestrian Egg) were not marked for one simple reason: Russia had no mark for the metal at that time.

External political considerations interfered, such as when artisans were called to arms in wartime. This first became a problem for Fabergé in the Russo-Japanese War which broke out in 1904, and then in the internal political problems which afflicted Russia in 1905. But the House of Fabergé suffered its heaviest depletion of artisans during World War I and documents exist in which Fabergé pleaded with the authorities to let him retain valuable craftsmen so work could continue.

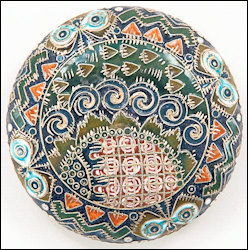

Rückert Silver-gilt and Cloisonné Pictorial Boxes in the Russian Style,

Workmaster Feodor Rückert, K. Fabergé beneath the Imperial Warrant,

88 Standard, Moscow, ca. 19102

(Courtesy McFerrin Collection)

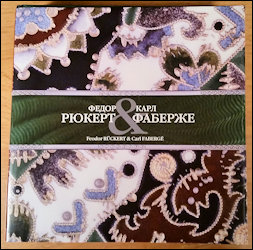

Encyclopedic Publication of 611 pages for the

Revyakin Collection of Old-Russian Style Objects3

Regrettably, most of Fabergé’s account books, design stock books4 and other records disappeared after the October Revolution of 1917. What became of many of these records remains a mystery. It is known the new Bolshevik authorities made unsuccessful efforts to find them because they wanted the names of Fabergé employees. Vladimir Averkiev, one of Fabergé’s close financial advisers, possibly hid the records. He disappeared after being tracked down and arrested in 1927. Averkiev had successfully hidden a trove of Fabergé jewellery, which only came to light in 1990. To survive the dangerous times following the October Revolution of 1917, former Fabergé employees were forced to maintain a discreet silence about their employer and their colleagues. Because of this wall of silence and the absence of official records, it has been a long and often difficult journey to discover answers to such simple questions as who were the Fabergé workmasters5. Some are still unidentified today.

So, when considering legitimate Fabergé items, particular questions need to be asked and answered, and this is best done by those who have worked in the field for many, many years. It is imperative to know well the Fabergé workmasters and their marks, as well as the house marks and the Russian hallmarks of the time. For example, any item with St. Petersburg marks for the years 1908-17 and stamped with Mikhail Perkhin’s mark would need very close inspection, since Perkhin died in 1903. Similar considerations led to the exposure of the so-called Nicholas II Equestrian Egg, purportedly given to the Tsar by his wife to celebrate the Romanov Tercentenary in 1913. But the egg carried the mark of Viktor Aarne, who had sold his workshop in 1904.

Potential Fabergé buyers should also note that Carl Fabergé himself was in reality, the general manager of a vast business enterprise, organized along very progressive lines. He is not known to have personally produced any object. He designed items and he approved nearly all other designs (sometimes his sons would do this, if Fabergé himself was unavailable), and he checked the finished objects, but he did not make them himself. His various marks represent the House of Fabergé, and its standards.

Physical clues are available to confirm genuine Fabergé pieces: the way hinges are so perfectly fashioned as to be all but invisible, the way a cigarette case closes, the way hardstone is carved, the methods of enameling, the chasing and engine-turning techniques, and above all, the meticulous attention to detail. But again, a practiced eye is needed if doubts arise. Provenance details also mean a great deal, and it is a huge bonus if the item retains its original case, or bill of sale. These testaments to an item’s origins automatically enhance its monetary value. The same remarks apply particularly to unmarked items, such as hardstone figures.

The lack of official Fabergé records caused problems for auction houses staging the first sales of Fabergé material between the two world wars. When Christie’s held the first major sale in London on March 15, 1934, there was little information to provide for prospective clients. It would be another 15 years before the first monograph on Fabergé, Peter Carl Fabergé (London, 1949), would be written by Henry C. Bainbridge, the joint manager of Fabergé’s London branch.

Gradually, a more complete picture of the output from the House of Fabergé has emerged. Occasional pieces of the jigsaw are still falling into place as more and more archival information emerges from Russia. This is just as well: the ever-increasing prices paid for Fabergé have given forgers the incentive to continue their illegal practices, some of them with a diligence that even Carl Fabergé may have grudgingly admired.

Catalogs provided by the major auction houses have, in general, become increasingly more sophisticated over the years. By the 1980s, Christie’s was able to provide the following guidelines for prospective buyers:

- Marked Fabergé, workmaster – in our opinion a work of the master’s workshop inscribed with his name or initials.

- By Fabergé – in our opinion, a work of the master’s workshop, but not with his mark.

- Marked with the Imperial warrant of – in our opinion a work of the master with his Imperial Warrant mark.

- Bearing…marks – in our qualified opinion, probably not a work of the master and bearing a later mark.

This is an excellent starting point for prospective buyers. Contemporary lot descriptions no longer contain these guidelines, however, they are nevertheless useful in tracing previous sales for a given lot.

So, is it really Fabergé?

With tongue firmly in cheek, this writer suggests: If the item carries the appropriate marks, meets the stringent stylistic and technical considerations of international experts, has a long provenance dating back to a wealthy original purchaser in St. Petersburg, Moscow or London, has its original fitted Fabergé case, and is listed in the London stock books or one of the known Fabergé design books, then it’s likely to have been made by the world renowned House of Fabergé!

2 Atzbach, John, “Workmaster Feodor Rückert” in McFerrin, Dorothy, From a Snowflake to an Iceberg, 2013, pp. 274-281.

3 Muntian, Tatiana, Feodor Rückert & Carl Fabergé, 2016.

4 Extant design records have been published in Christie’s (London), Designs from the House of Fabergé, April 27, 1989; Snowman, A. Kenneth, Fabergé Lost and Found: The Recently Discovered Jewelry Designs from the St. Petersburg Archives, 1993; Tillander-Godenhielm, Ulla, et al. Golden Years of Fabergé: Drawings and Objects from the Wigström Workshop, 2000.

5 Over 500 individuals are listed with biographical details in Lowes, Will, and Christel Ludewig McCanless, Fabergé Eggs: A Retrospective Encyclopedia, 2001, pp. 175-245; Fabergé, Tatiana F., Kohler, Eric-Alain, and Valentin V. Skurlov. Fabergé: A Comprehensive Reference Book, 2012, pp. 119-293. See also summary of books about Fabergé’s workmasters written by Finnish authority, Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm, in Searching for “Genuine” Fabergé section in this edition of the newsletter.

A.

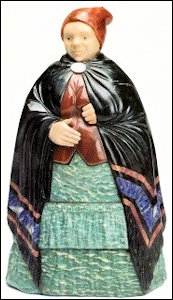

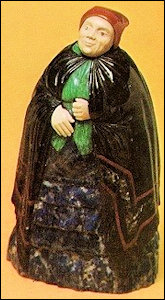

B.

C.

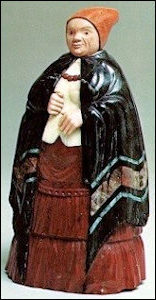

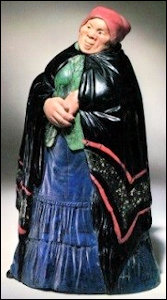

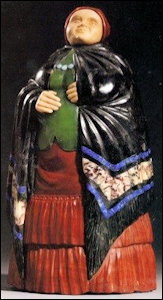

A. Fabergé Merchant from the Estate of Dr. E. Lionel Pavlo, Walking Stick Marked Fabergé, Workmaster Mikhail Perkhin. Christie’s New York, April 19, 1990, Lot 238, estimate $150,000-200,000, passed in or withdrawn. Later identified as perhaps made by Mikhail Monastyrsky2.

B. Fabergé Wealthy Farmer, Gold Mounts by Michael E. Perchin (sic), Offered in an on-line auction until December 17, 2012, by Lauritz Auction House, Denmark. Estimate DKK 800,000/€ 107,264, sold at DKK 425,000/€ 56,938.

C. Merchant by Vasily Konovalenko, Russian Stone Carver (1929-1989), Private Collection (Nash, Stories in Stone: The Enchanted Gem Carvings of Vasily Konovalenko, 2016, xvi, p. 200-201)

The owner of the merchant (A.), Dr. E. Lionel Pavlo died in 19897, and so did the stone carver Konovalenko, who was known to make more than one copy of a theme he liked. Most of his life he lived in Russia, but in 1981 he immigrated to New York and worked with his brother-in-law, the stone carver Naum Nikolyavesky. According to a 1994 article8 written by Géza von Habsburg, Nikolyavesky was arrested in 1969 and “condemned to years of hard labor in Siberia” for his criminal activity of selling Fabergé forgeries to foreign diplomates in Moscow. von Habsburg states that Nikolyavesky lived in Brooklyn, New York, where he created Fabergé forgeries with his group of Russian artisans. In a 2014 video recorded at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts on the topic of Fauxbergé9 von Habsburg calls them the “Brooklyn Forgers”, whose work shows up everywhere, from eBay to auction houses. In the video von Habsburg relates the story of a man who came to him in Geneva with a genuine Fabergé cigarette case and a stone carving of a woman dressed as a Russian match-maker (further details unknown at this time). As an auctioneer for many years, he knew this piece from seeing it at auction, and had been told by colleagues it was not Fabergé, but by Nikolyavesky. He conveyed this information to the man, who simply walked away “without batting an eye.” The man turned out to be Nikolyavesky himself, hoping to sell his work at another auction.

The book by Yuri Brokhin, Hustling on Gorky Street: Sex and Crime in Russia Today10 published in 1975 contains a chapter devoted to Naum Nikolyavesky, and his criminal exploits. The chapter title is ‘The “Successor” to Fabergé’ and in it the author recounts the story of a police sting in which stone carvings of a coachman, troika, two hippos, a cat, and a golden samovar with ebony handles were confiscated11. At the end of the chapter Brokhin talks about a 1974 exhibition of Vasily Konovalenko’s work in Leningrad, and he mentions stone carvings of Old-Russian Types, “a dustman, Cossacks on agate horses, a matchmaker, guitarist, shepherds, accordion players.”12 Fabergé’s workshops carved the same subjects.

During the course of research undertaken years ago another series of hardstone figures surfaced which may have a connection to Konovalenko and his brother-in-law, Nikolyavesky.

D.

E.

F.

G.

H.

D. Merchant’s Wife by A. (sic, earlier cited as Vasily) Konovalenko, Moscow, 1970’s. Collection of the State Historical Museum13. (Ed. note: Face and hands are made of ceramics, a material never used by the Fabergé firm.)

E. Fabergé Marriage Broker (Svatkah) Sotheby Parke Bernet, New York, May 16-18, 1974, lot 478, estimate $20,000-25,000, price realized $14,000.

F. Fabergé Marriage Broker (Svatkah) Sotheby Parke Bernet, New York, May 9, 1975, lot 265, lot description cites the successful sale of a similar figure from the 1974 sale above, passed in or withdrawn.

G. Fabergé Marriage Broker (Svatka) Christie’s Geneva, May 12, 1981, lot 92, signed beneath in Cyrillic characters K. Fabergé, price realized SFr 65,000 (ca. $33,00014 at that time). The auction catalog description states “figure has served as a model for numerous replicas”, and then promotes the exclusive use by the Fabergé firm of a rediscovered vitreous man-made material named purpurine15.

H. Fabergé Matchmaker (Svaha) Christie’s London, June 13, 2007, lot 224, apparently unmarked, missing the sapphires for the eyes (Ed. note: Old-Russian Types without gold parts were not usually hallmarked.) Estimate £300,000-400,000/$600,000-800,000/€440,000-580,000, passed in or withdrawn.

- Which of the match makers (D.-H.) was presented in person to Géza von Habsburg by Nikolyavesky16, and which match maker has the Konovalenko/Nikolayvesky connection mentioned by Brokhin in his book?

- Which figure is the genuine Fabergé hardstone match maker – the marriage broker (G.) carved in a satirical manner which also fetched the largest amount of money in one of two successful auctions? Or the one with the missing eyes (H.)?

In Konovalenko’s 2016 catalog published by the Denver Museum of Nature & Science there is another piece that gives one pause. A cane handle (I.)17 in nephrite with a silver dog head and a Fabergé-like guilloché enamel hilt with gold swags and bows. These aesthetically disjointed pastiches are commonly seen for sale on the internet (J.), and even in some auction houses as original Fabergé pieces. Dogs, hippos, rabbits, and birds are all mixed with imperial cyphers, swags on guilloché enamel, and precious stones.

I. Cane Handle

by Vasily Konovalenko

The moral of this story? Buyer beware! Do your homework, before investing in art. Forgers have made a fortune from these hardstone carvings, and continue to do so.

2 Marina Lopato (Head Curator of the Dept. of Western European Silver, Hermitage Museum St. Petersburg) in von Habsburg, Géza, et al. Fabergé: Imperial Craftsman and His World, 2000, enumerates the story of Mikhail Monastyrsky, a well-known forger of “figures à la Fabergé”, pp. 386-388.

3 Synopsis of “Windows into Russian Life: Fabergé’s Hardstone Figures” presented by Timothy Adams, Christel McCanless, and Annemiek Wintraecken at The World of Fabergé in St. Petersburg 100 Years Ago, 2014 Fabergé Museum Symposium, St. Petersburg, Russia.

4 Fabergé, T., Kohler, and Skurlov in Fabergé: A Comprehensive Reference Book, 2012, p. 578, suggest other reasons about this forgery in their essay, “A Fatal Error in Hallmarking” about this forgery.

5 Nash, Stephen E., Stories in Stone: The Enchanted Gem Carvings of Vasily Konovalenko, Denver Museum of Nature & Science, 2016.

6 Nash, pp. 200-201.

7 Pavlo was a highly successful civil engineer and suspension bridge builder, born in the Ukraine, arrived in the USA in 1929, earned his civil engineering Ph.D. at the Massachusetts Institute in Technology in 1932. (Wiki)

8 von Habsburg, Géza, “Fauxbergé” with the subtitle, “The Plague of Forgeries Besetting the World of Fabergé Has Developed into a Multi-million–dollar International Industry. Even Organized Crime Is Involved”, Art & Auction, vol. 16, no. 7, February 1994, pp. 76-79.

9 von Habsburg, Géza, Fauxbergés: The Master Forgers, 2014; see also footnote 4 above.

10 Book review published by The New York Times on October 19, 1975, entitled “Three-kopeck Opera” by Susan Jacoby; “Faking It In Moscow.” Art News, vol. 74, October 1975, pp. 20–22.

11 Brokhin, p. 183.

12 Ibid, p. 184.

13 von Habsburg, Géza and Marina Lopato, Fabergé: Imperial Jeweler, 1993, p.388, the modus operandi of Nikolyavesky and Konovalenko in making forgeries is discussed on pp. 166-167.

14 Forecast Chart.

15 Fabergé, T., Kohler, and Skurlov, 2012, p. 390, suggest this figure was made by the Fabergé firm.

16 von Habsburg, Géza, Fauxbergés: The Master Forgers, 2014.

17 Nash, p. 165.

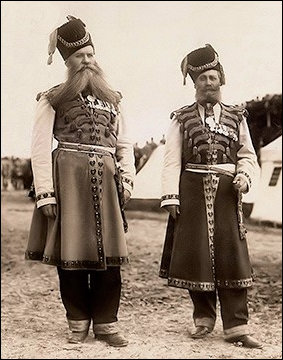

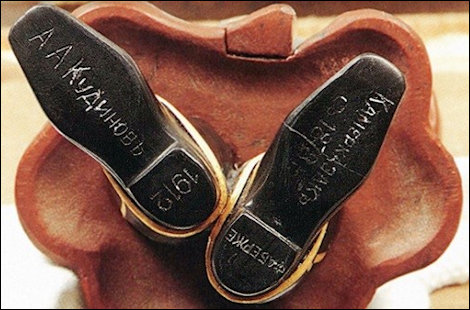

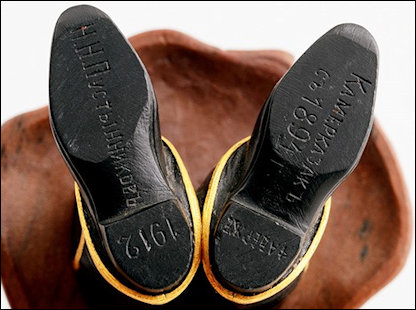

Left and right: The Fabergé hardstone figure of Chamber Cossacks A.A. Kudinov, who guarded Empress Maria Feodorovna

from 1878 to 1915, and N.N. Pustynnikov, who served Empress Alexandra Feodorovna from 1894 until 1917.

Photographs Courtesy of Pavlovsk State Museum and Gafifullin1 (left) and Wartski, London (right).

Center: Archival photograph of Kudinov and Pustynnikov in their ceremonial dress at annual military

maneuvers presided over by Nicholas II in 1913.

(Courtesy GIA)

- 1912: Both figures are created by Fabergé and purchased by Nicholas II, who owned 21 of these Fabergé portrait figures.

- 1918: After the Russian Revolution, some of the emperor’s hardstone figures were in possession of Agathon Fabergé (second son of Carl Fabergé, 1876–1951), Armand Hammer, and Wartski, London. The Pustynnikov figure is brought to the United States for sale by Armand Hammer2, dealer in Russian art, 1930s-1950s.

- 1925: The Kudinov figure (A.) goes on display at the Pavlovsk State Museum Collection until 1941.

- December 11, 1934: Hammer Galleries in New York sells the Pustynnikov figure for $2,250 to Mrs. George H. Davis of Manhattan and Rhinebeck, New York.

- 1956: The Kudinov figure goes back on display at the Pavlovsk State Museum.

- October 26, 2013: The Pustynnikov figure (B.) is offered for sale by the descendants of Betty Davis, the original American owner. The piece has remained in the family’s hands since 1934 and has not been exhibited for 79 years, until it is auctioned at the Stair Galleries in Hudson, New York.

- The major auction houses in this case study (Sotheby’s, pair #1 and Doyle, pair #7) presented the kamer kazaks in their elegant hardcopy catalogs mailed in advance to potential bidders and catalog subscribers, and also on the internet. The smaller auction houses in three countries relied mainly on the internet to present their wares. Free-lance arts journalist, Daniel Grant in a 2014 Huff Post Blog3 states it succinctly, “Christie’s, Sotheby’s and Heritage Auctions all have created their own in-house online bidding platforms, but most every other auctioneer relies on an outside company, the largest being the Manhattan-based LiveAuctioneers. …” The Benko study found two more internet umbrella agencies active in selling the chamber cossacks – The Saleroom, the home of art & antiques auctions affiliated with the Antiques Trade Gazette, and UKauctioneers. More or less identical auction lot descriptions with the terms ‘inscribed Fabergé’, and ‘cast cold painted bronze figures, dated 1912’ appear over and over again on the aforementioned websites. It also became quickly apparent that most lot descriptions included a reference to Sotheby’s London December 2015 financial success of selling the first pair (#1)4 of two cast and cold painted figures to come on the market for £25,000 (including the premium).

-

The authors then attempted to learn about the descriptive terms of cast and cold painted figures. Being aware that Fabergé’s original Chamber Cossacks (A. and B.) were carved from Russian gemstones, the question arose – why would there suddenly be multiple copies in another medium, not known to have been used by Fabergé except possibly in the production process? The specific Russian gemstones as identified by Adams and McCanless in their essay without the use of instruments to test gemological properties for Pustynnikov are shown in the next illustration.

Russian gemstones used by Fabergé in 1912 to create the 7.5 in. (19 cm) portrait figure of Chamber Cossack Pustynnikov (B).

(Photograph Courtesy Wartski, London, Chart Credit GIA, p. 140)Fabergé research colleague Tim Adams coached the authors in understanding the terminology used in pairs #1 – #9.Cast iron toys, also used with bronze: The way new and old iron is painted is another indication of age. Old iron usually was decorated with fairly heavy paint, most frequently some type of oil based enamel. New pieces are typically decorated with a much thinner paint which is usually a water based acrylic. Old and new paints were also applied differently. Many old pieces were dipped in paint, not painted with a brush (although small details may have been added by a brush). Many new pieces are painted with air-powered spray guns to speed production. The use of thicker paint and the heavier coatings of paint produced by dipping produces a distinctive wear pattern in original painted cast iron toys.

Cold painting: The term is used online to describe colorful bronze or spelter figures, but almost no one explains what it means. Cold-painting was a technique popular during the art-deco period, which started in the 1920s. Bronze figures, most of them made in Vienna, were covered with enamel paint.

The authors of this essay noted two minor discrepancies in relation to the art-deco time period and dates suggested in the definition and in the auction lots:

- Sotheby’s auction (pair #1) suggests “their creation almost surely pre-dates the mid-1920s” (Ed. note: The Fabergé firm closed in 1917/18).

- Jackson’s International Auctioneers (pair #9) suggests “probably after 1920 and perhaps even later”.

Adams also wondered if the multiple objects under the hammer from 2015-2017 could have been licensed by Fabergé and outsourced to a toy manufacturer during Fabergé’s time?

Soles: Inscriptions by Fabergé are hand-carved into the Russian gemstone material. The inscriptions in the multiple kamer kazaks are the same from figure to figure since they are cast into the metal rather than engraved.

Fabergé’s Hand-carved Inscriptions for Kudinov (A.) and Pustynnikov (B.) on Russian Gemstones

(Courtesy GIA, p.135)

Cast-metal Inscriptions for Kamer Kazaks, Pair #3

(Courtesy Rowley’s Fine Art Auctioneers and Valuers)- Alexander von Solodkoff5 in 1986 and Géza von Habsburg6 in 2014 discuss the conundrum that animals, flowers and hardstone figures carved from semi-precious stones are not always marked, and they further suggest a large number of copies and forgeries have come on the market. Both scholars postulate Fabergé never made anything in a series but produced some of them several times with variations due to the high demand by his clients. In this case study another question arose – would the Fabergé firm which used gold, silver, platinum, a large variety of Russian gemstones, leather, wood, etc., select bronze for a series of “look-alike” kamer kazaks?

- Provenances of the kamer kazaks in the online auctions are scarce, while the prices realized detailed in the chart below appear to reflect the wisdom of the buyers at auction.

Prices Realized for 2015-2017 Online AuctionsPAIR AUCTION HOUSE PRICE REALIZED ADDITIONAL INFORMATION #1 England Sotheby's London £25,000 ... their creation almost surely pre-dates the mid-1920s ... #2 England Fryer & Brown £7,800 plus 23% premium Auction house only in business for one year, liquidated January 2017. #3 England Rowley's DNS (Did Not Sell) #4 England Hutchinson & Scott Withdrawn #5 England Adam Partridge DNS #6 England Piers Motley DNS Consigned to Piers and Motley by a gentleman from Devon. Previous provenance cited as “bought from Bearnes, Hampton & Littlewood”. Email dated August 24, 2017, from Bearnes, Hampton & Littlewood advises “they have not had any Fabergé figures for sale”. #7 USA Doyle $15,000 This auction lot is not listed as part of the Fabergé section in the hard copy catalog. #8 Scotland Callan £4,500 From the auction house website, the figures “were discovered wrapped up in a towel in a drawer of underwear, during a house clearing in Largs”, Ayr, Scotland.

Ayshire Post, May 12, 2017: “Fabergé at Flog It £25K Figures under Hammer” announces the BBC production being filmed at Culzean Castle on the coast of Scotland.#9 USA Jackson's International $2,500 Probably after 1920 and perhaps even later. The accompanying United Kingdom map shows the counties in which the kamer kazaks were sold.- Arts Journalist Daniel Grant in a recent Wall Street Journal article7 cautions that “online auctions open the world to art buyers. But it also opens those buyers to a world of risks.” The author concludes with these words of wisdom from a New York-based art adviser Todd Levin: ‘I don’t allow my clients to buy just from a JPEG, sight–unseen, no eyes laid on it, no condition report. …But some, do anyway.’

Other unanswered questions:

- Tatiana Fabergé et al. in K. Fabergé I ego prodolzhateli, St Petersburg, 2009, p. 96, state: “In 1927, a metal figure of Kudinov was found in the Armoury among objects which had belonged to the Imperial Family.”8 Is there archival documentation which can be studied in more detail? Contact: Christel McCanless

- Did the ca. $6 million price realized in 2013 for the genuine Fabergé Pustynnikov Kamer Kazak (B.) set the stage, and then did the sale of the first pair (#1) for £25,000 in December 2015 cause this flood of multiples to appear on the market?

- Five (5) pairs sold and four (4) did not – would sellers flood the market with so many objects at once, or did the same pair sell more than once in a period of 19 months? The UK map shows a somewhat orderly process of exposing the objects to the public both in the England and Scotland, and later in the USA, i.e., first at a major auction house, and then systematically, at least in the UK, in the second tier market?

- Are the pairs in #1 – #9 authentic Fabergé?

ENDNOTES:1 Gafifullin, Rifat, The Works of the Fabergé Company from the Late XIX – Early XX Century in the Collection of the State Museum of Pavlovsk. Pavlovsk State Museum, St. Petersburg, 2014, pp. 48-50. In Russian.

2 von Habsburg, Géza, “The Hammer Years, 1930’s-1950s” in Fabergé in America, 1996, pp. 56-61.

3 Huffington Post Blog.

4 Sotheby’s, London, December 1, 2015, Lot 446 (The catalog note on Sotheby’s website is quite long and very informative.)

5 McCanless, Christel Ludewig, Fabergé and His Works: An Annotated Bibliography of the First Century of His Art, 1994, Entry #1331.

6 von Habsburg, Géza, Fauxbergés: The Master Forgers, 2014.

7 Grant, Daniel, “The Art of the Online Deal”, Wall Street Journal, October 24, 2016, R4.

8 Sotheby’s, London, December 1, 2015, Lot 446.EggsFabergé Egg Mysteries: A Literature Searchby Christel Ludewig McCanlessScholars in any area of research do not always agree on findings and suggested hypotheses. Pros and cons of the debate lead to lively discussions. Egg mysteries – not yet solved and still open for further research – are illustrated with dates given by the producers of each respective egg. The last two images on the collage show the only object with a solid provenance and a confirmed date. The objects are listed briefly in this essay with commentaries from links and citations found on Fabergé egg-specific websites, books, journals, and Wikipedia.Major Resources Consulted:- McCanless, Christel Ludewig, Fabergé and His Works: An Annotated Bibliography of the First Century of His Art, 1994.

- Fabergé, Tatiana, Proler, Lynette G., and Valentin V. Skurlov, The Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs, 1997.

- Lowes, Will, and Christel Ludewig McCanless, Fabergé Eggs: A Retrospective Encyclopedia, 2001.

- Link of Times Collection, Fabergé: Treasures of Imperial Russia by Géza von Habsburg, 2004.

- Fabergé, Tatiana F., Kohler, Eric-Alain, and Valentin V. Skurlov, Fabergé: A Comprehensive Reference Book, 2012.

- Imperial Egg Chronology of the Fabergé Research Site by Will Lowes and Christel Ludewig McCanless (uploaded 2017).

- Mieks Fabergé Eggs by Annemiek Wintraecken (recent updates cited).

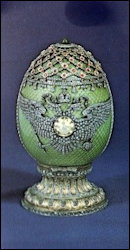

A. 1885-89

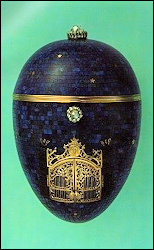

B. 1890

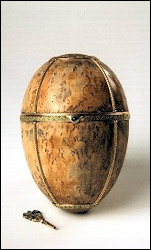

C. 1892

D. 1902

E. 1913

F. 1917

G. 1917

H. 1917

1917 Unfinished Blue Tsesarevich Constellation Egg

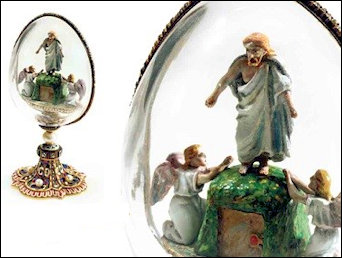

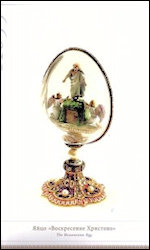

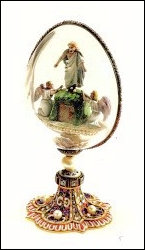

in the Fersman Mineralogical Museum, MoscowPrior to the sale of the Forbes Magazine Collection to Viktor Vekselberg in 2004, Christopher Forbes postulated that the Resurrection Egg (A. below left) is “the missing surprise from the Renaissance egg (A. below right), as it perfectly fits the curvature of the Renaissance egg’s shell, has a similar decoration in enamel on the base, and features a pearl, which is mentioned in the invoice for the Renaissance egg but not present on that egg”.The Resurrection Egg in the Link of Times Collection is housed in the Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. The concluding statement in the link above states, “A reliquary of similar shape by Fedor Afanassiev with silver-gilt figures of the risen Christ flanked by two angels is in the Maryhill Art Museum, Goldendale, Washington”. In 2001, Lowes and McCanless (p. 147) first suggested the foregoing statement – it is an error! Thanks to research by DeeAnn Hoff and Kris Mills the mystery has been unraveled, and is now corrected in this issue of the Fabergé Research Newsletter (see Case Study V. in the Museums section)

A. 1885-1889 Resurrection Egg and 1894 Imperial Renaissance Egg with the Resurrection Egg

(Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia)Resurrection Egg

- Fabergé, T., Proler, and Skurlov, The Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs, 1997, p. 79.

- Lowes and McCanless, Fabergé Eggs: A Retrospective Encyclopedia, 2001, pp. 146-148.

- Mieks Fabergé Eggs (updated April 2016).

Renaissance Egg

- Fabergé, T., Proler, and Skurlov, The Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs, 1997, pp. 116-117.

- Lowes and McCanless, Fabergé Eggs: A Retrospective Encyclopedia, 2001, pp. 38-42.

- Link of Times Collection Treasures of Imperial Russia, 2004.

- Imperial Egg Chronology, Fabergé Research Site (2017).

- Mieks Fabergé Eggs (July 2017).

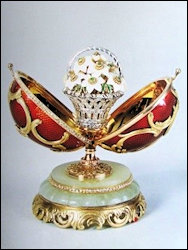

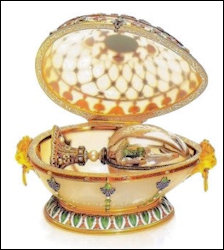

B. 1890 Spring Flowers Egg

(Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia)From Wikipedia: “The authenticity of this egg has been cast in doubt by Fabergé experts. Its method of construction is noticeably subpar, having diamonds of mismatched size and with inferior quality attachments, and two halves that are asymmetrical, failings not characteristic of Fabergé’s workshop. It also does not bear the expected maker’s marks, and has other design features which may signal its status as a counterfeit piece. Although it has been examined many times by experts who have often agreed with its original attribution, there is no record of who might have supposedly given it to the Romanovs and no correspondence between Fabergé and either of the last two Russian emperors to confirm its commissioning or its delivery. Neither does it have a clearly documented provenance or record of ownership. Although its materials (gold, diamonds, enamel, etc.) are typical of Fabergé’s workshop, the method of construction and inadequate/incomplete history cast significant doubt on its authenticity.”- Fabergé, T., Proler, and Skurlov, The Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs, 1997, p. 80.

- Lowes and McCanless, Fabergé Eggs: A Retrospective Encyclopedia, 2001, pp. 148-151.

- Link of Times Collection, Fabergé: Treasures of Imperial Russia, 2004.

- Fitzgerald, Nora, “Fabergé Egg Is a Bad One, Russian Expert Contends”, Art News, April 26, 2005.

- Mieks Fabergé Eggs (October 2016).

C. 1892 Dr. Metzger Egg Clock

(Wikipedia)The verdict of a lawsuit pertaining to the egg states:“High Court ruled Fabergé egg is a fake. The judge’s comments came at the end of a long-running trial during which the owner of the so-called ‘Dr. Metzger Egg Clock’, Mr. Michel Kamidian, sought millions of pounds of compensation for the damage done to his treasure while it was being shipped to an exhibition in America in 2001.” (“Art Dealer Finds His Fabergé Is a Fake“, Daily Telegraph [London], June 27, 2008.)The July 2008 court decision England and Wales High Court, Commercial Court, Decisions gives further details. The lengthy history of this egg clock is told in the essay entitled, “A Genuine Artefact Labelled a Fake” by Fabergé, T., Kohler, and Skurlov, 2012, pp. 580-581. On December 13, 2011, the egg described as “in the style of Fabergé” sold at a Rosebery (London) to an unknown buyer for £75,000 (including expenses). Estimate for lot 190 was £2,500-3,000.

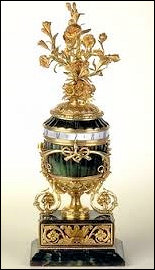

D. 1902 Empire Nephrite, Also Known as Alexander III Medallion Egg

The provenance of this missing egg from the Imperial Egg Chronology, Fabergé Research Site:- April 14 (OS), 1902. Would have been presented to Marie Feodorovna, a gift from Nicholas II; cost 6,000 rubles. Probably housed in the Anichkov Palace.

- September 16-20 (OS), 1917. One of forty or so eggs sent to the Armoury Palace of the Kremlin in Moscow by the Kerensky Provisional Government for safekeeping.

- February-March 1922. Probably transferred to the Sovnarkom, the Council of People’s Commissars.

- Whereabouts unknown.

- Lowes and McCanless, Fabergé Eggs: A Retrospective Encyclopedia, 2001, pp. 78-79.

- Fabergé, T., Proler, and Skurlov, The Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs, 1997, pp. 159.

- Publication in Russian and English entitled, The 1902 Empire Nephrite Easter Egg by Fabergé, edited by Alexander von Solodkoff with essays by other scholars (2014), suggests the missing egg has been found. However, the majority of Fabergé scholars have not yet accepted the theory.

- Skurlov, Valentin, Fabergé, Tatiana, Kvashnin, Sergei, and Anatoly Perevyshko, François Birbaum, Headmaster at Fabergé Firm, 2016, St. Petersburg, Kirov, Geneva, pp. 164-183. In Russian. Published as part of the 1996 Memorial Fund Carl Fabergé editions.

- Mieks Fabergé Eggs (May 2016).

E. 1913 Nicholas II Equestrian Egg

(Christie’s Geneva)Sold at Christie’s Geneva April 27, 1977, Lot 481, for SFr 550,000 ($220,000) to Eskander Aryeh of Great Neck, Long Island (NY). In 1985, The New York Times reported it to be, “the highest price ever paid in dollars for a Fabergé egg at auction”. A lawsuit between the auction house for refusal to pay the buyer’s fee was settled with Aryeh paying $400,000 (including legal fees and interest) for an egg attributed to Fabergé workmaster Viktor Aarne*. In 1985, the Aryeh egg came on the market again, but was withdrawn before the auction and then followed by another lawsuit, Aryeh vs. Christie’s. McCanless, Fabergé and His Works: An Annotated Bibliography of the First Century of His Art, 1994, includes 27 citations about the authenticity of the egg and the legal wrangling from April 1977- May 1989.[*Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm in her 1980 publication, Carl Fabergé and His Contemporaries, p. 40, states Aarne (active workmaster 1891-1904) had returned to Finland in 1904 after selling his St. Petersburg workshop. (Ed. note: Therefore, the Nicholas II Equestrian with a 1913 date could not be Aarne’s work.)]

- von Habsburg, Géza, “Fauxbergé”, Art & Auction, vol. 16, no. 7, February 1994, p. 77.

- Fabergé, T., Kohler, and Skurlov, Fabergé: A Comprehensive Reference Book, 2012, p. 577.

A variety of opinions have surfaced about two unfinished eggs for presentation at Easter 1917 – The Great War (World War I) was still raging, Emperor Nicholas II and his family were arrested and eventually executed, and it is now generally accepted based on a 1922 letter from a trusted employee of the Fabergé firm, that the Fabergé eggs were never delivered. Should one be surprised that during the intervening one hundred years efforts were underway to fill the vacuum? Three of these efforts are discussed here – F. Twilight Egg/Night Egg (1917) G. “Finished” Karelian Birch Egg (1917) and H. “Finished” Blue Tsesarevich Constellation Egg (1917). There is a happy ending for one unfinished egg – the 1917 Blue Tsesarevich Constellation Egg which was found in the early 2000’s in a Moscow museum, and was on view from June-September 2017 at the Stone Carving and Jewelry History Museum in Yekaterinburg, Russia.

F. 1917 Twilight Egg/Night Egg

(Christie’s Geneva and Wikipedia)Sold at Christie’s Geneva, November 10, 1976, Lot 184, for SFr 100,000 ($40,000) and last seen in the 1977 Victoria & Albert Museum Fabergé exhibition.- Fabergé, T., Proler, and Skurlov, The Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs, 1997, p. 81. Authors after examining all the relevant documentation eliminated the Twilight Egg/Night Egg from the list of imperial Fabergé eggs.

- Lowes and McCanless, Fabergé Eggs: A Retrospective Encyclopedia, 2001, pp. 171-173. Twilight Egg details written before the details of the genuine egg (see I.-J. for text and images) were published by two Russian museum collection keepers, Tatiana Muntian, Kremlin Museum, and Marianna Chistyakowa, Fersman Mineralogical Museum, in the January 2003 issue of the British journal Apollo.

- Fabergé, T., Kohler, and Skurlov, Fabergé: A Comprehensive Reference Book, 2012, p. 576.

- Mieks Fabergé Eggs (April 2016). In Dutch.

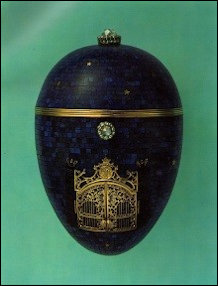

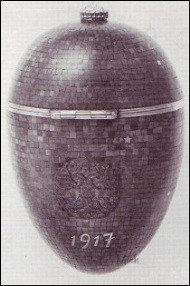

G. 1917 Karelian Birch Egg Design Sketch

(Tatiana Fabergé Archives)

“Finished” Karelian Birch Egg (Exhibition:

The Art of Fabergé at the Kostroma State

Historical, Architectural & Arts

Museum Reserve, 2010, p. 22-23)An original design sketch for the 1917 Karelian Birch Egg is extant for an egg assumed to be unfinished by scholars.

Citations for a series of publications, each of them including a variety of details:

- 1997 Fabergé, T., Proler, and Skurlov, The Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs, pp. 61-63 discuss the extant design sketches.

- 2001 Lowes and McCanless. Fabergé Eggs: A Retrospective Encyclopedia, pp. 144-145, pieced together various archival details known about the egg at the time.

- 2001 “Birch Egg publicly reappeared when a private collector from the United Kingdom, the descendant of Russian emigrants, sold it to Alexander Ivanov, the Moscow collector who owns the Fabergé Museum in Baden-Baden, Germany”. (Wikipedia)

- 2003 Fabergé, T., “Das Kaiserliche ‘Birkenholz-Ei’ von 1917 – ein Wiederendecktes Osterei (The Imperial Wooden Birch Egg of 1917 – A Newly-discovered Easter Egg)” in von Habsburg, Géza, Fabergé – Cartier: Rivalen am Zarenhof, pp. 141-143. In German.

- 2004 Both the “finished” 1917 Karelian Birch Egg and the 1917 “unfinished” Blue Tsesarevich Constellation Egg were on display at the 2003-04 Kunsthalle Fabergé/Cartier exhibition in Munich, Germany. (Farnham, Alan, “Egg Hunting, Pro Division: Eight Fabergé Easter Eggs Went Missing after 1917. Where Are They?” Forbes, April 12, 2004)

- 2005 Varoli, John, “Have Two New Imperial Fabergé Eggs Surfaced in Russia? Leading Jewelry Experts Are Not So Convinced, But Refuse to Say So Publicly”, The Art Newspaper, June 30, 2005.

- 2010 The egg from the Alexander N. Ivanov Collection in the Fabergé Museum in Baden-Baden, Germany, was shown in a Kostroma (Russia) exhibition (cited under the illustration above). At press time the egg is not shown on the museum’s website.

- 2012 Fabergé, T., Kohler, and Skurlov, Fabergé: A Comprehensive Reference Book, p. 440, feature four images of the completed egg and its extant design sketch. Other written documentation shown in previous publications is not included.

- 2016 Mieks Fabergé Eggs information gathered from various websites (August 2017).

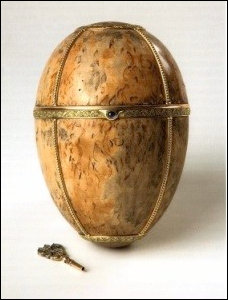

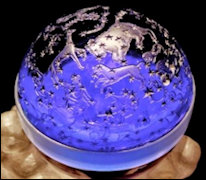

There are two claims for the original “unfinished” 1917 Blue Tsesarevich Constellation Egg – a “finished” egg in the Fabergé Museum in Baden-Baden, Germany (H.) and the unfinished egg in the Fersman Minerological Museum in Moscow. Pros and cons of the lively debate are given below.

H. 1917 “Finished” Blue Tsesarevich Constellation Egg

(Fabergé Museum in Baden-Baden, Germany)Wikipedia entry lists this egg as a “second egg” under the heading Constellation (Fabergé egg). The text continues – “Russian millionaire Alexander Ivanov claims that he owns the original (and finished*) egg. In 2003–2004, he said that he acquired this egg in the late 1990s and affirms that ‘the Fersman Museum erroneously continues to claim that it has the original egg.’ Western authorities do not agree. However, Mr. Ivanov’s egg is in the Fabergé Museum in Baden-Baden which houses part of his Fabergé collection.”[*Ed. note: Cupids are missing.]

I.

J.

K.

L.

M.

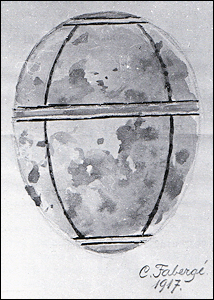

N.I. – N. 1917 Unfinished Blue Tsesarevich Constellation Egg in the Fersman Mineralogical Museum, Moscow.I. Design Sketch Signed C. Fabergé, 1917. (First published in Snowman, The Art of Fabergé, 1953, plate 355; 2012 Fabergé, T., Kohler, and Skurlov, Fabergé: A Comprehensive Reference Book, p. 441)

J. Apollo Magazine Cover Announcing the Rediscovery of the Egg, January 2003, vol. CLVI, no. 491, 10-13.

K. Materials of the Components: Egg Halves – Dark Blue Glass | Cloud Base – Opaque Rock | Crystal Silver Putti and Nephrite Pedestal, Shown in the Sketch But Missing

L. – N. Unfinished Egg Components with a Modern White Band, View of the Night Sky on the Day of the Tsesarevich Alexei’s Birth, Gold Rim. Bands are used to secure and stabilize the two glass halves. (Courtesy Fersman Mineralogical Museum, Image M: Realms of Gold)

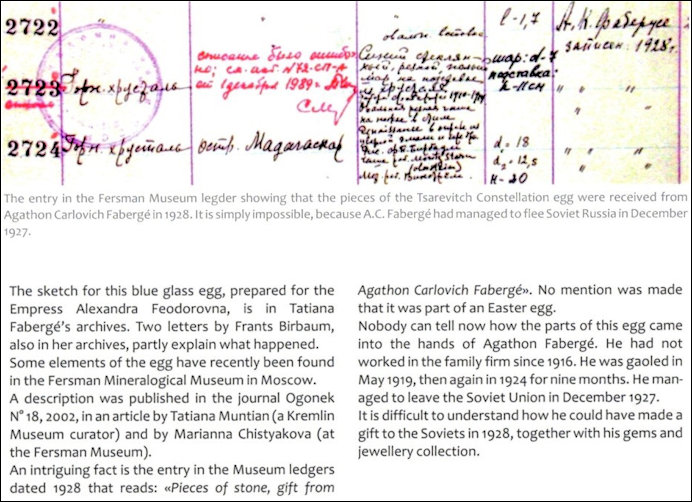

The Imperial Egg Chronology on the Fabergé Research Site uploaded in 2017 contains a summary of the archival details and provenance of the 1917 unfinished egg:A letter in the files of Tatiana Fabergé, the great-granddaughter of Carl Fabergé, also sheds light on the 1917 Easter egg, which was in production when Tsar Nicholas II abdicated on March 2 (OS), 1917. The letter is from Fabergé’s chief designer, François Birbaum, to Fabergé’s eldest son, Eugène, and was written in August 1922. In part it says:‘One thing I remember for certain is the order of an egg for the Tsar by Ivashev (Editor’s note: A designer in Fabergé’s St. Petersburg headquarters ca. 1898-1918) and Carl Gustavovich [Fabergé]. This, you may remember, is an egg of dark blue glass incrusted with the constellation of the day of the Tsarevich’s birth. The egg is supported by silver cherubs and clouds of opaque rock crystal. Unless I am mistaken, the egg contained a clock with a revolving face. The execution of this egg was interrupted by the war. The cherubs and the clouds were finished, but the egg itself with its incrustation and the pedestal were not finished. Where all this has disappeared to I have no idea, and when I visited the House after the raid, I found no trace of this article.’ (Fabergé, Proler, & Skurlov, Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs, London, 1997)

Birbaum then goes on to describe what may well be the Karelian Birch [G.] Egg being made for the Dowager Empress Marie Feodorovna in 1917. He concludes:‘It is quite possible that these were orders to Carl Gustavovich with miniatures by Zuiev, but as I did not design them, I cannot say anything about them.’ (Fabergé, Proler, & Skurlov, Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs, London, 1997)Eugène Fabergé had apparently written to Birbaum for details of these eggs after receiving a letter from Henrik Wigström in Finland, seeking payment for work on the two eggs. Wigström was Fabergé’s senior workmaster at the time.Provenance:

1917. In production for presentation to Alexandra Feodorovna on April 2 (OS), Easter Sunday. Never presented; the unfinished egg apparently remained at Fabergé’s premises until removed by Agathon Fabergé.

1925. Elements of the egg presented to Alexander F. Fersman of the Moscow Mineralogical Museum by Agathon Fabergé (1876-1951, second son of Carl Fabergé, gemstone expert/administrator).

2002. Discovered unfinished in the Fersman Moscow Mineralogical Museum and authenticated with an original design sketch.

At press time the website of the Fersman Mineralogical Museum, Moscow, is not online. However, an article by Mikhail Generalov in Our Heritage, No. 83-84, 2007, “Last Imperial Easter Egg Fabergé: What the Stars Told” includes the selected bibliography from the Fersman Museum:

- Muntian T.N., Chistyakova M.B. A Symbol of a Disappearing Empire. The Rediscovery of the Fabergé Constellation Easter Egg // Apollo. January 2003, Pp. 10-13.

- Muntyan T.N. Fabergé. Easter Gifts. M., 2003. Pp. 72-79.

- Chistyakova M.B. Fabergé’s Mysteries // Antiques. 2005. #10 (31). Pp. 20-23.

- Chistyakova M.B. Not Finished by Fabergé Imperial Easter Egg of 1917 // Antiquarian Review. 2005. #3. Pp. 14-16.

- Belousova Т.М. Fatal eggs // Top secret 2005. # 7. Pp. 29-31. In Russian.

- Fabergé T.F., Proler L.G ., Skurlov, V.V., The Fabergé Imperial Eggs. London, 1997. P. 62.

The main artist of Fabergé, François P. Birbaum wrote in 1922:‘An egg of blue glass, on which the constellation of the day in which the heir was born was incrusted. The egg was supported by cupids made of silver and clouds of frosted rock crystal. If I am not mistaken, there were watches with a rotating dial inside. Making of this egg was interrupted by the war. Comets were ready cupids, clouds, the egg itself with incrustations and the pedestal was not finished.’Additional references in this egg discussion:- Muntian, Tatiana N. and Marianna B. Chistyakowa, “Ein Symbol des Endes eines Kaiserreiches: Die Wiederentdeckung von Fabergés ‘Konstellation-Ei’ (A Symbol of the End of the Imperial Empire: The Rediscovery of Fabergé’s Constellation Egg)” in von Habsburg, Géza, Fabergé – Cartier: Rivalen am Zarenhof, 2003, pp. 144-145. In German. Essay written for the exhibition catalog of the 2003-04 Munich Kunsthalle venue, Fabergé / Cartier: Rivals at the Czar’s Court where the egg was on view for the first time.

- Varoli, John, “Have Two New Imperial Fabergé Eggs Surfaced in Russia? Leading Jewellery Experts Are Not So Convinced, But Refuse to Say So Publicly“, The Art Newspaper, June 30, 2005.

- In 2012, Fabergé, T., Kohler, and Skurlov, Fabergé: A Comprehensive Reference Book, 2012, p. 441, do not concur with some of the findings concerning this egg:

- “Fabergé’s 1917 Blue Tsarevich Constellation Egg” (Courtesy of Royal Russia News, February 8, 2013).

- Ms. Wintraecken on her Mieks Fabergé Eggs website reports on both 1917 eggs (April 2016).

And yes, there are still seven missing Fabergé eggs out of total of 50 Imperial eggs made. Annemiek Wintraecken on her Mieks Fabergé Eggs website has a very comprehensive discussion on missing Fabergé eggs, surprises and stands (April 2017).Will Lowes and Christel McCanless in their Imperial Egg Chronology on the Fabergé Research Site have lengthy entries about seven missing Imperial Fabergé eggs, designated with the symbol

, and in some instances known black and white illustrations.

, and in some instances known black and white illustrations.The hunt is still on for missing genuine Imperial Fabergé eggs, their surprises or stands. In the meantime, caveat emptor!

MuseumsFauxbergé in Museums: A ReviewCompiled by Christel Ludewig McCanlessWith Contributions from Newsletter Readers, Timothy Adams, Pat Hazlett, DeeAnn Hoff, Rich Hutting,

Steve Kirsch, Kristin Mills, Peter Schaffer, Museums and Scholars Who Have Had the Courage to Expose FauxbergéFor more than ten years, an essay, “Authentic Fabergé, Fauxbergé…What Is It?” complete with resources to learn more about genuine Fabergé objects has been on my Fabergé Research Site. Auctioneers, dealers, museum curators, and collectors are being inundated with forgeries, made in the style of Fabergé, and reproductions. In a quick review of a file folder I have kept for years on this topic, I found some highlights to share. Some of us “senior” Fabergé enthusiasts remember the surprise (or was it a total shock!) when we stepped into the last room of the 1996 Fabergé exhibition at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. Géza von Habsburg1 had elected to display a portion of the 132 forgeries owned by the New Brunswick Museum in St. John, Canada. What an amazing teachable moment for museum visitors! A sampling of these objects identified as fakes in 1994 graces my “Authentic…” web page to this day.

Fauxbergé: Perfume Bottle, Inkwell, Brush Pot

(New Brunswick Museum, St. John, Canada)

Fauxbergé Egg

(Courtesy McFerrin Collection)- The UPI (United Press International) wire service in connection with the Richmond venue carried an article with the title Fabergé Show Exposes Market in Fakes by Frederick M. Winship, UPI Senior Editor, February 13, 1996. During 16 months the traveling blockbuster exhibition was seen at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond, New Orleans Museum of Art, and the Cleveland Museum of Art.

- Steve Kirsch, a newsletter contributor, agreed to share the story of his Fauxbergé website:

My interest in Fabergé began in 1997 with a visit to the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. I recall standing in front of the 1896 Egg with Revolving Miniatures for a good 15 minutes, studying the composition and reading about the egg’s presentation. I then began to look at the other Fabergé objects and was just fascinated. I am a collector by nature, so I thought it might be fun to buy a few pieces. Upon my return to New York I began to investigate, but I was quickly deterred by the astronomical prices at auction. For Christmas 1998, my wife surprised me with a nephrite bowl with gold mounts and enamel handles.

During those early years, I was constantly checking to see if there were Fabergé pieces for sale on eBay. Everything looked good to me, but my mentor always shot down anything I showed him by dismissing them outright as fakes. I would argue that they had Fabergé marks, and ask why he thought they were fake. “You just know!” is what he told me. Eventually as I began to see more and more genuine Fabergé objects at auctions and exhibitions, I also began to recognize that nearly all of the eBay pieces were fakes. In 2000, I began my Fake Fabergé Photos website partly to open up discussions about the fakes, but also to learn about website design. Ninety-five percent of my fake photos were downloaded from eBay ads. Initially, I had intended to post a lot of photographs of genuine objects as well, but it seemed more productive to just post links to the better collections. I am still surprised to this day how many people are familiar with my site. Eventually, it became obvious to post more new fake material does not really provide any further education. In my essay entitled, “How Can You Tell the Real Thing from the Fakes?” I have written down the lessons I learned from my journey with Fabergé objects, and it is my hope they are a guide for future collectors to avoid the obvious pitfalls.

- Peter Schaffer, proprietor of A La Vieille Russie in New York City, shared “a few tips on making sure that if Fabergé is what you want, Fabergé is what you get” in a PBS (Public Broadcasting Service), Antiques Roadshow program broadcast by Television WGBH in Boston on January 17, 2000. One of the things I learned from watching Schaffer’s program is that “marks are now made with lasers that can trace a real Fabergé mark unto a fake piece.” Reflecting on my Fabergé fascination history while writing this article, I realized I had met WGBH before – on Sunday, October 22, 1978, WGBH-TV began a 14-program mini-series with each segment lasting from four to six minutes featuring objects from the Forbes Magazine Collection. I was a new Fabergé enthusiast then and saw them all!

Case Study IV: Fauxbergé in the McFerrin CollectionIn 2001, after Dorothy and Artie McFerrin acquired the first two “Fabergé” objects for their collection now numbering in the hundreds, they presented them to an appraiser at the popular British and American Antiques Roadshow2. The verdict – fakes! The McFerrin’s learned from this experience and sixteen years later in April 2017 the beautiful Dorothy and Artie McFerrin Gallery housing their collection of more than 600 Fabergé and Russian decorative art objects described in two books3 was unveiled at the Houston Museum of Natural Science in Texas (Ed. note: Hurricane Harvey did not damage the collection).

One display case in the gallery challenges the visitor to distinguish between genuine Fabergé objects and Fauxbergé.

Fabergé and Fauxbergé Display Case in the McFerrin Gallery, Houston, Texas

(All Photographs by Pat Hazlett Except the Pencil Holder Close Up, Christie’s New York)

65

117

118 and 385

557

555

588 and 556- 65 Paperknife, Gabriel Nykänen, workmaster mark GN

– active 1889-1917

– active 1889-1917 - 117 Fauxbergé Egg, first McFerrin acquisition

- 118 Bonbonnière Egg on Stand, Mikhail Perkhin, workmaster mark М.П – active 1886-1903

- 385 Pill Box, Fabergé, no workmaster

- 557 Fauxbergé Letter Opener

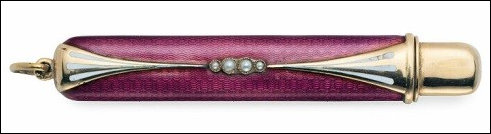

- 5554 Pencil Holder, Henrik Wigström, workmaster mark H.W.

– active 1903-1917, provenance: Nancy Reagan

– active 1903-1917, provenance: Nancy Reagan - 588 Rhodonite Etui, possibly a calling card case (research incomplete), Henrik Wigström, workmaster mark H.W.

– active 1903-1917

– active 1903-1917 - 556 Fauxbergé Box

Rich Hutting, a docent at the Houston Museum of Natural Science, using the Fauxbergé egg for museum tours for children, writes:

Recently a nine-year-old girl approached the McFerrin Fauxbergé object at the Houston Museum of Natural Science. “Mister, why is that egg so drab?” she asked. After complimenting her use of vocabulary, I replied, “because it’s not Fabergé.” I usually spend about ten minutes with visitors examining real Fabergé pieces with a magnifying glass. We focus on detail, color, and guilloché. Patrons are always mesmerized. Then we scrutinize the Fauxbergé. I ask our visitors, “what’s wrong with this object? Why ISN’T it Fabergé?” Almost immediately, someone mentions dull color, overwrought metalwork, or awkward design. My magnifying glass reveals inferior guilloché technique. Visitors are fascinated. As interpreters we appreciate Fauxbergé. It’s a great teaching tool!

Over the years the Antiques Roadshow experts and Fabergé Research Newsletter readers have uncovered other Fabergé fakes. It appears even auction houses have fallen into the trap.

Fauxbergé in Blue!

(Christie’s New York,

April 19, 2002, Lot 179.

Lot descriptions on

p. 91 have been

transposed.)- Timothy Adams, a newsletter contributor shares his story:

Almost ten years ago it came to my attention that a Fabergé Imperial Egg was to be the center of a Russian art exhibition at a museum in Southern California. The flier advertising the show featured the “Imperial Egg” on the cover. It was obvious to me at first glance the egg was a fake, and not even a good one. The flat and muddy enamel and the application of excessive imperial insignia with truly bad detail-work gave it away to anyone who knows Fabergé’s work. My phone call to the museum’s curator was awkward, but was necessary to keep this piece from being vetted via a museum exhibition. I introduced myself to the curator and suggested perhaps a second and third opinion by just sending the photographs to two world-renown Fabergé dealers, A La Vieille Russie in New York City, and Wartski in London, would help. She did just that, and sure enough the egg was pulled from the show.

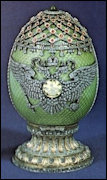

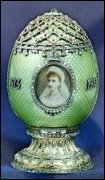

I attended the opening and introduced myself to the curator, who thanked me for saving their reputation, and told me after looking at some genuine Fabergé pieces and comparing them to the fake the quality difference was now obvious. Later I learned the lender was upset and stood by the fact that the egg was real, since it came with a long history, and was fully researched with photographs of Nicholas II and his mistress to whom it was given. When I asked where the lender had bought it, the answer was – last week on eBay for $6,000. Well, upon hearing that I knew who sold it to the unsuspecting lender. A man in Sophia, Bulgaria, whom I had been following for years on the Internet produces Fauxbergé out of old and new pieces, stamps them, and adds long detailed descriptions of their provenance complete with archival photos of the original owners, usually from the Imperial family. The egg in question was dark-red enamel. I checked on eBay the following day, and sure enough, the exact same egg, but now in green enamel was for sale at $6,000. So, beware, provenance stories are just stories until they are verified with archival documents. The more exposure one has to real Fabergé, the more one is be able to spot Fauxbergé.

- The next word of caution – caveat emptor – for my newsletter readers and me came in a phone interview with Peter Schaffer, “Will the Real Fabergé Stand! A Dealer’s Perspective” (Fabergé Research Newsletter, Fall 2009). He shared a technique used to authenticate pieces from his Power Point program: “I show my audience Fabergé objects with increased magnification from one view to the next. If the larger images continue to hold up to this detailed scrutiny, then it tells me it is a real Fabergé. Fakes cannot take this kind of close examination – the quality dissipates quickly.”

- 2011/2012 were banner years for Fabergé enthusiasts. For two years guest curator Dr. Géza von Habsburg had “studied and authenticated Fabergé objects in the Pratt Collection at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, identified those made by other makers, and added editorial notes to forgeries and objects with uncertain origins.” The New York Times (June 30, 2011) headlined the article about the venue, A Fabergé Exhibition Without Fauxbergés by Eve M. Kahn. The article mentions the shameless way Armand Hammer used “Fabergé hallmarking tools to reattribute early 1900’s pieces made by other Russian goldsmiths or their French archrival Cartier.”5 Romanov portraits clipped from postcards and newspapers were inserted into frames sold by Hammer, and most objects were advertised with an imperial provenance. The Virginia exhibition, Fabergé Revealed, was shown with supplemental loans from the Matilda Geddings Gray Collection, the Hodges Family Collection, and the Dorothy and Artie McFerrin Collection. It later traveled from 2012-2016 without the supplemental loans to six cities in the USA, Canada, and the Palace Museum in Beijing, China.

- Anthony Brandt’s article “Fab or Faux?” in Town & Country, November 2012, 126-29, 152-3, examines the million-dollar, buyer-beware realm of Fauxbergé. Beginning with a hands-on session at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, the author learned about fakes and forgeries by interviewing authorities in the field of Fabergé.

ENDNOTES:1 von Habsburg, Géza, et al., Fabergé in America, 1996, Appendix 1: “Fauxbergé”, pp. 329-338.

2 ANTIQUES ROADSHOW is a trademark of the BBC and is produced for PBS by WGBH under license from BBC, Worldwide.

3 McFerrin, Dorothy, From a Snowflake to an Iceberg: The McFerrin Collection, 2013, and Fabergé: The McFerrin Collection – The Opulence Continues… 2016.

4 New object for this McFerrin #, not in 2016 Opulence book.

5 Blumay with Edwards, The Dark Side of Power: The Real Armand Hammer, 1992, (pp. 95-108).Case Study V: Maryhill Museum of Art, Goldendale, Washingtonby DeeAnn Hoff and Kristin Mills, Independent Researchers (USA)

Maryhill Museum of Art

(Maryhill Postcard)

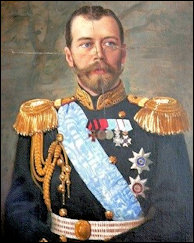

Partially-Restored Portrait of

Emperor Nicholas II

(Photograph by Kristin Mills)High on a remote bluff overlooking the mighty Columbia River from the Washington State side stands a grand mansion housing the Maryhill Museum of Art. The museum’s park is the only touch of green for miles. Visitors encounter an adventurous drive along a winding road, tracing a cliff plunging several hundred feet down to the river, which makes one hope not to encounter any oncoming large trucks. The elegant structure was constructed by entrepreneur road-builder (this irony was not lost on us!) and railroad magnate Sam Hill (1857-1931) at the turn of the century, and stands as a monument to art and as a memorial to himself. While named for his wife, Marie, the museum (though still unfinished, and not completed until 1940) was “dedicated” in 1926 by Marie, Queen of Romania. Today the museum houses a collection of objects, including the Queen’s gown worn to the coronation of Emperor Nicholas II, which she included in her substantial donation of memorabilia to commemorate her visit. Passing through the entry, into the main gallery of the museum, a portrait of Emperor Nicholas II greets visitors; it has been partially restored from a slashing it suffered while hanging in the Russian Embassy in Beograd (Belgrade), Serbia. Although a gift from the Romanian Queen, its provenance is through her daughter Marie (Marija Karađorđević), who was Queen of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, and later Queen of Yugoslavia.Our visit was planned to enjoy the Columbia River Gorge and the Maryhill Museum, but more specifically to examine the ‘Resurrection Egg’ (also known as the Transformation Egg) and other objects in their collection identified on the display case text as being from the workshops of Carl Fabergé.

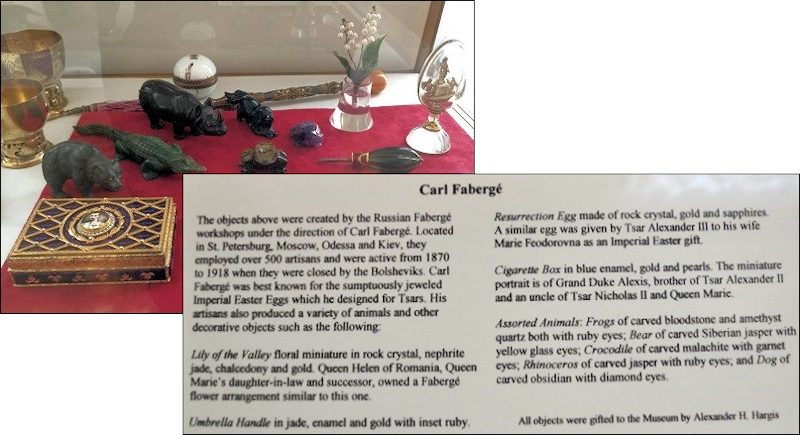

Maryhill Display Case with Objects Labeled Fabergé

(Photographs by Kristin Mills and DeeAnn Hoff)Maryhill Museum ‘Resurrection Egg’On August 5, 2016, with the kind assistance of Curator Steve Grafe, the authors were able to study the egg donated by Seattle engineer, Alexander H. Hargis. Our case study report is divided into three parts –

- Chronological highlights from a literature search in preparation for the study visit.

- Review of the paper trail of the Maryhill Museum archival documents.

- Observations after examining the egg out of its display case.

B. Snowman, A. Kenneth,

The Art of Carl Fabergé,

Second Edition, 1962,

plate 317.

C. Maryhill Museum ‘Resurrection Egg’ with Its Base Enlarged

(Photographs by Kristin Mills)Chronological Highlights:March 16, 1934 Christie’s (London) auction.1 Reporter for The Times (London) suggests ‘A century hence the work of Carl Fabergé…will probably be realizing high prices in the auction room, but yesterday a collection of objects d’art made by him failed to realize more than £1,367. Only one lot, the reliquary of rock crystal and enamel enriched with pearls and diamonds (Ed. note: 1885-1889, or also cited as a pre-1899 Resurrection Egg, shown in A. above), attained three figures, or £110. The First Imperial Egg sold for £85.’2

1962 A. Kenneth Snowman3, chairman of the British jewelry dealer Wartski, who arranged the first Fabergé loan exhibition in 1949, published a black and white photo (B.) of the Resurrection Egg.

2001 Lowes and McCanless published the following in their retrospective egg encyclopedia4, “Feodor Afanasiev is known to have made an Easter egg for Fabergé based on the Perkhin Resurrection Egg presented to Marie Feodorovna in the 1880s (sic). Afanasiev’s example was made at least a decade later and is now in the Maryhill Museum of Art, Goldendale, Washington.”

2004 Géza von Habsburg5 in the catalogue raisonné of the Vekselberg Collection (now housed in the Fabergé Museum in St. Petersburg, and formerly in The Forbes Magazine Collection), concludes the discussion of the Resurrection Egg with this statement, “A reliquary of similar shape by Fedor Afanasiev with silver-gilt figures of the risen Christ flanked by two angels is in the Maryhill Art Museum, Goldendale, Washington.”

2017 Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm after a thorough archival study of the Fabergé workmasters confirms the dates Afanasiev qualified as a master goldsmith are unknown. In 1903, he was still a journeyman. Most trained goldsmiths remained journeymen all their active lives as they chose to work for someone else. Therefore, if he had crafted the Maryhill ‘copy’ in the time period suggested, it would have been marked with the master’s mark of his employer.

Review of Maryhill Museum Archival Documents:Objects attributed to Fabergé were donated to the museum by Seattle engineer, Alexander Hargis (born ca. 1925).6 In his letter to the museum dated October 25, 1967, he offers:

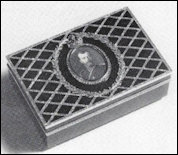

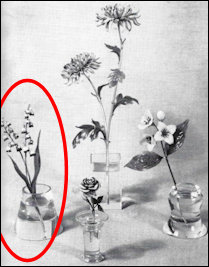

“12 eggs of semi-precious stone in a satin-lined presentation case…The case has a Russian marking on the inside…Knowing the Maryhill Museum has items from Eastern Europe, I thought these might be of interest to you.” A letter followed on December 5, 1968, stating he had mailed the Miniature Eggs as well as: “… a cigarette box which is Russian enamel on gold or bronze with pearls & a miniature portrait of Grand Duke Alexandrovich (sic), brother of Tsar Alexander III.”Both the miniature eggs and the box (to be addressed by the authors later in this article) were received by the museum, and further objects from Mr. Hargis, notably the ‘Imperial Russian Easter Egg’ (C.) and the ‘Lily of the Valley’ flower study included in our study, are documented in his letter of delivery and museum accession documents dated 1976. In a document provided by the donor, and preserved in the museum files, the ‘Imperial Easter Egg’ is thus described: Fabergé Egg / Russian / Gold; Sapphire; Rock crystal. 5 3/8 inches high & 1 1/8 inches base diameter. Readers are advised the purple text below is lifted directly from Snowman, A. Kenneth, The Art of Carl Fabergé, Second Edition, 1962, p. 79.

Accession # 1976.04.001 ~ Egg. Artist – Fabergé. Received 1976. Gift of Alexander H. Hargis. Description: “Fabergé Imperial Russian Easter egg in the form of a monstrance, this Resurrection Egg is made in the manner of the Italian Renaissance. The three gold figures in the group stand on and beside the Sepulcher. The whole resurrection scene is contained within a superbly carved rock crystal egg, the two hemispheres held together by a line of sapphires mounted in a band of gold. (Ed. note: Only the word ‘diamonds’ in Snowman, p. 79, here in the description is replaced with ‘sapphires’.) The plinth supporting the egg is carved rock crystal with separating bands and beubaches [trim] of gold and sapphires.

A similar egg was given by Czar Alexander III to Marie Feodorovna (Illustration B. above, text copied from Snowman, 1962, plate 317). Maryhill’s egg is marked on the base with mark of workmaster Fedor Afanasiev. Also visible are gold marks 72 (18k) and “koloshnik” (kokoshnik).

In a letter to Christel McCanless dated December 4, 1995, the museum curator states: “Maryhill Museum of Art owns 22 pieces by Fabergé…acquired as part of the collection of objects and memorabilia related to Queen Marie of Romania (1875-1938).”In 2003, Maryhill Museum notes the donor is quoted:

“The three resurrection figures in this egg are of a gold metal (not tested for gold) and sit on a gold-colored plinth. There is no enameling on these figures as there is described on the ‘Imperial Transformation Egg’ (Ed. Note: Earlier name for the Resurrection Egg). The two hemispheres of the egg are held together by a band of gold imbedded with blue sapphires, those bands are repeated at the base and just under the egg. There are NO pearls as described in the Transformation Egg.” Hargis, Alexander, H.Authors observations based on viewing the Maryhill Egg out of its display case:- Existing tarnish is inconsistent with gold used as a material. Marks of gold stated in museum documents are ‘72 (18k) and koloshnik (kokoshnik)’. The assay mark is not clearly distinguishable even when examined with a jeweler’s visor by Kristin Mills.

- Hallmarks: Workmaster mark ФA

for Feodor Alekseievich Afanasiev (b. 1870-after 1927).

for Feodor Alekseievich Afanasiev (b. 1870-after 1927).

- If the egg dates to 1885-89, or pre-1899 as suggested by a 2004 Fabergé Museum publication, and Afanasiev was still a journeyman in 1903, then he would not be using a master’s marks. Therefore, more recent research findings negate the statement made in error by Lowes and McCanless in 2001 (see endnote 4), and subsequently repeated in other publications.

- Snowman in his 1962 publication on page 124 suggests Afanasiev made “small objects of fantasy usually enameled.” There is no enameling on the Maryhill egg.

- The ФA maker’s mark appears to be an ‘overstrike’ where another oval mark has been removed. von Habsburg and von Solodkoff7 in discussing Fauxbergé objects mention, “…adding Fabergé’s punch and thus doubling their value.”

- Technical details:

- While stated as ‘rock crystal’, this egg had more the look and feel of glass/lead crystal. The rim on the base was unevenly ‘finished’. (C.)

- When compared with the Fabergé Museum Resurrection Egg (A.), the Maryhill egg (C.) displayed poor proportions between the height of the figures to the globe of the egg, as well as the shape of the egg itself. The vertical hash-marks surrounding the half/round ground on which the scene sits appear to be drawn from the Perkhin creation, or at least an image of it.

- Did the Snowman black and white illustration (B.) suggest the ‘two-tone’ Maryhill egg copy and the other objects discussed below? For example, a cigarette case and a flower study labeled Fabergé appear to mirror photographs published in the 1962 Snowman book.

Nephrite Box

(Snowman, 1962, plate 130)

Maryhill Cigarette Case

Youssoupoff Easter

Egg

(Snowman, 1962,

plate 393)

Wooden Base with a Metal Rim

of the Maryhill Cigarette Case

(Photographs 2 & 4 by Kristin Mills)Maryhill Document: Accession# 1968.06.001 ~ Cigarette Case. Artist – Fabergé. Received 1968. Gift of Alexander H. Hargis. Description: Cigarette case of gold, pearls, and blue enamel. The cover of the box bears a miniature portrait of Grand Duke Alexis (sic), brother of Tsar Alexander III, who was the father of the last Tsar of Russia Nicholas II.Authors observations:

- We cannot cite an extant presentation box on which Fabergé used pearls, diamonds would have been the preferred accent.

- The identification of the portrait is incorrect. The photograph is Prince Felix Youssoupov (Sr.), Count Sumarkov-Elston as shown in the well-known Youssoupoff 25th Anniversary Egg.

- The use of wood with a metal rim is not known in objects from the Fabergé workshops.

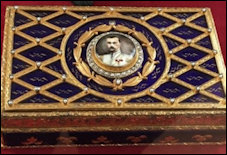

Flower Study in the Royal Collection

(Snowman, 1962, plate 303)

Maryhill Museum

Flower Study

(Photograph Kristin Mills)Maryhill Document: Accession # 1976.04.002 ~ Lily of the Valley. Artist – Fabergé. Rcvd. 05/07/1976. Gift of Alexander H. Hargis. Description: “Lily of the valley floral miniature, vase of rock crystal, stems in matte gold, leaves in nephrite jade, flowers in green and white chalcedony. Stamens in facet-cut sapphires. Signed on stem K.F. in Russian symbols.”Authors observations: The lilies of the valley Fabergé object in the Royal Collection is created from pearls with rose diamonds, nephrite leaves and is not signed. The authors noted in the Maryhill flower study a dark discoloration around the individual flowers appearing to be corrosion. The shape of the vase, the number of blossoms on each stem, the angle of the stem as it enters the vase, and the position and configuration of the leaves is clearly ‘after’ the image of the Fabergé flower study in Snowman, 1962, plate 303.Still illusive is the series of 12 miniature eggs of semi-precious stones mentioned in Maryhill Museum documents. In a letter from Mr. Hargis to Mr. Clifford Dolph of Maryhill Museum, dated Oct. 25, 1967:

“… Several years ago I acquired 12 eggs of semi-precious stone in a satin-lined presentation case. The eggs are about 1 3/4 inches in length and are of such stone as moss-agate, malachite, lapis lazuli, obsidian, aragonite, etc…The case has a Russian marking on the inside which I can’t read …” In a subsequent letter dated Dec. 5, 1968, Mr. Hargis writes that he mailed the egg collection to Maryhill Museum.In spite of references to the association of these objects to Queen Marie in correspondence and museum documents, there appears to be no viable connection in the records at the museum. Queen Marie commissioned original pieces from the Fabergé firm. One extant example is a brooch incorporating a personal monogram of her own design.8In conclusion, the specific objects studied in this essay suggest a common source of inspiration, namely, the second edition in 1962 of The Art of Carl Fabergé by A. Kenneth Snowman. In 1979, von Habsburg and von Solodkoff active as authors, dealers and in the auction world summarize this unfortunate trend of Fauxbergé by stating, ”Complete forgeries, almost without exception bearing the Fabergé signature; …the greater part, however, appeared after publication of Snowman’s book, from 1953 onwards.” The Maryhill gift unfortunately appears to be a case in point based on the comparisons in this case study.

The authors wish to thank Mr. Grafe and the staff of the Maryhill Museum for granting permission to study objects in their collection.

ENDNOTES:1 McCanless, Christel Ludewig, Fabergé and His Works: An Annotated Bibliography of the First Century of His Art, 1994, p. 34, entry #36.

2 The First Imperial Egg presented in 1885 cost 4151 rubles/$3193, and by 2014 its value was $82,857. No values are available for the Resurrection Egg, since it was not an Imperial Fabergé Egg. Source: Benko, Riana, “Statistical Cost Analysis of Fabergé’s 50 Imperial Easter Eggs”, Fabergé Research Newsletter, Fall 2015.

3 Snowman, A. Kenneth, The Art of Carl Fabergé, Second Edition, 1962, p. 79, and plate 317.

4 Lowes, Will, and Christel Ludewig McCanless, Fabergé Eggs: A Retrospective Encyclopedia, 2001, pp. 146-47, 179.

5 von Habsburg, Géza, Fabergé: Treasures of Imperial Russia, 2004, p. 124.

6 The authors attempted to reach Mr. Hargis through his office.

7 von Habsburg, Géza, and Alexander von Solodkoff, Fabergé: Court Jeweler to the Tsars, 1979, pp. 149-150.