Newsletter 2015 Fall

1896 Monogram Designed

by Queen Marie

(Courtesy Diana Mandache,

Royal Romania)

1899-1908 Queen Marie of Romania Brooch

by Fabergé

(Courtesy McFerrin Collection)

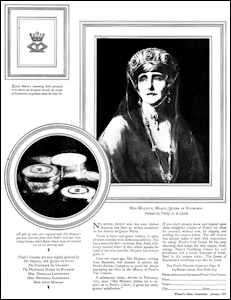

Acclaimed for her beauty from childhood, Marie sat for portraits by such famous artists of the period as Philip de László (1869-1937), Hungarian portrait painter, and Friederich August von Kaulbach (1850-1920), German portraitist and historical painter. Sandra de László in A Brush With Grandeur, 2004, 32-3, dates the de László portrait of the Queen wearing a sapphire and diamond kokoshnik-style tiara originally owned by the Grand Duchess Vladimir of Russia. The artist had met the queen in Vienna in 1899 when she was Crown Princess and his own career had just begun. While he repeatedly refused invitations to Romania due to all that Hungary suffered at the hands of Romania, he did paint the Queen in London in 1924, and found her: ” . . . uncommonly intelligent . . . she also knows how to make use of her great charm and lilac eyes.” (Prince Nicholas of Greece, My Fifty Years, 1926, 253-4)

Philip de László Portrait of Queen Marie of

Romania, 1924

(Munn, Geoffrey, Wartski, The First One

Hundred and Fifty Years, 2015, 182-3)

Pond’s Skin Creams Advertisement

(Woman’s Home Companion, January 1927)

Youth is hers-and great vitality, in spite of years crowded with strenuous activity. She has a beautiful skin-unlined, firm, fresh, with lovely natural color! A skin which speaks for itself of the wise care Her Majesty has always given it.

Over two years ago, Her Majesty, writing from Bucharest, was pleased to permit the Pond’s Extract Company to quote her words expressing her faith in the efficacy of Pond’s Two Creams.

A subsequent letter, written in February, 1925, says: ‘Her Majesty wishes me to repeat, as to Pond’s Cream, it gives her daily greater satisfaction.’

- Kristin Mills, Houston, attempted to redeem the ‘coupon’ at the New York City address. The amusing response she received was that they did not have time to help with ‘school projects’.

- I sent a historical inquiry to Unilever, London. The company acquired Ponds in 1986 and Fabergé in 1989. No response was forthcoming.

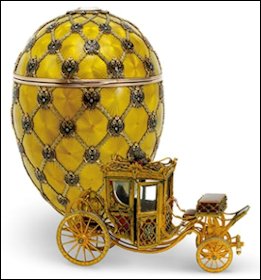

In the Artie and Dorothy McFerrin Collection on view at the Houston Museum of Natural Science in Texas, a Fabergé brooch with the distinct monogram designed by Crown Princess Marie of Romania using her artistic talent is featured on a lozenge-shaped brooch/chiffre. The sketch dated to 1896 incorporates a stylized M below the Romanian crown, and the brooch is hallmarked 1899-1908 for the Moscow workshops of Fabergé. This suggests the chiffre was made before Marie became Her Majesty, The Queen of Romania in 1914. It appeared on the auction market – Sotheby’s Geneva, November 16, 1989, Lot 418, with a later case stamped Wartski, and in 2006 was on loan from a private collection to the Wartski London venue, Fabergé and the Russian Jewelers: A Loan Exhibition, item 228. The historical details to whom the pin was presented are unknown at this time.

Ruslan and Ludmila by Aleksandr Pushkin (1799-1837)

A vale before them spreads; upon it

Rise clumps of spruces, and a mound

Looms farther out, its strangely round

And very dark and gloomy summit

Against the bright blue sky outlined.

Our youthful knight at once divined

That ’twas the Head before them showing;

The steed speeds on, more restive growing;

Across the plain its great hooves thunder….

And lo! – they’re close, they’re nearly there;

Before them is the nine days’ wonder,

It fixes them with glassy stare.

It is a thing repulsive, horrid:

Its inky hair falls on its forehead;

Drenched of all life, the hue of lead

Its face is, while the huge lips, parted,

And, like the cheeks, of colour bled,

Disclose clenched teeth; over the Head

Its hour of doom hangs. Our brave-hearted

And doughty knight rides up and faces

Its sightless gaze; the midget graces

The horse’s rump. “Hail, Head!” Ruslan

Cries loudly, for the Head to hear him.

“He who betrayed you is undone!

Look! Here he is, none now need fear him!”

These words the Head revivified

And in it roused new, fresh-born feeling.

It looked down at them, and, revealing

All of its anguish, moaned and sighed.

Our hero it had recognized,

And at the midget, nostrils swelling,

Stared, full of venom undisguised.

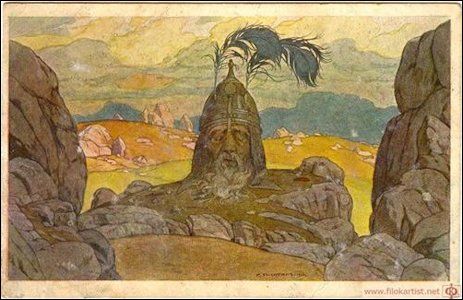

Severed Head of Golovo by Ivan Bilibin, 1900 Art Nouveau Painting

for Ruslan and Ludmila Opera

(Wiki)

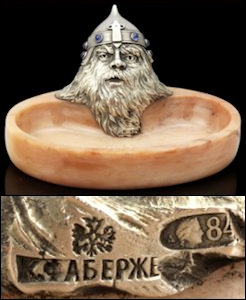

Aventurine Pin Tray with a Fabergé Mark

with Gem-Set Silver Head of Golovo Based

on Pushkin’s Poem

(Courtesy Bonhams London)

Gem-set Silver Inkwell on a Red Marble Base

(Courtesy Christie’s New York)

Gem-set Silver Casket Containing over 5 Kilos

of Silver, Acquired by an Asian Private Collector

for $707,603

(Courtesy Sotheby’s London)

Whilst still a student himself, Pushkin drew upon fairytales from his childhood for the adventures of a Russian warrior hero who searches tirelessly for his wife Ludmila, abducted by the evil wizard Chernomor. The quest by Ruslan leads him to a hill which reveals itself to be Golovo, the giant severed head of Chernomor’s brother. Ruslan initially attacks the head, but is persuaded to take up a magical sword and join forces to fell Chernomor in order to avenge the wizard’s brutality. The opera with the same name was produced in 1842 at the Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre in St. Petersburg and again in 1846 at the Moscow Bolshoi Theatre, where it has since been performed several hundred times. An early 20th century production at the Marinsky Theatre featured set designs by Konstantin Korovin. Other artists such as Ivan Bilibin (illustration above) and Nikolai Ge depicted Golova so the form was familiar to Russian audiences.

The Bonhams’ dish comprises a silver head with Golova’s characteristically full eyebrows and beard. He wears a traditional helmet set with cabochon sapphires and perches upon a base of aventurine quartz. The composition is reminiscent of an inkwell formed as a silver head upon a marble stand (Christie’s New York, October 20, 1998, Lot 37). Both relate to yet another version, also modeled in high relief but this time formed as a casket (Sotheby’s London, June 3, 2014, Lot 656, see additional details in a video in Auctions below). All three depictions of Golova are distinctly different in appearance despite sharing the same source of inspiration.

Although we do not know the precise circumstances that led to the group drawn from Ruslan and Ludmila, they are among Fabergé’s most distinctively Russian objects: Not only is the subject matter home-grown, but the references to traditional jewelry techniques in the cabochon sapphires and the unabashed celebration of indigenous hardstones all point inwards to native traditions and well away from the West as ultimate arbiter of taste.

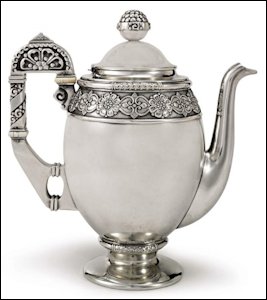

Fabergé Silver Coffee Pot, Moscow, 1908-1917,

Inventory Number 42249

Russian Art Week is a bi-annual event which takes place in May/June and November/December. The major auction houses of Christie’s, Sotheby’s, Bonhams and MacDougall’s all join together to present a series of Russian sales in London. Several Russian exhibitions and related cultural events also take place. (Courtesy Russian Art Week Website)

November 30, 2015 Christie’s London Important Russian Art

Christie’s Daily offers news, views and expert insights from the Art People. A recent offering included an advertisement for a Fabergé documentary and in the last segment stunning Fabergé auction lots offered during the Spring 2015 auctions.

December 1, 2015 Sotheby’s London Russian Works of Art, Fabergé & Icons

Darin Bloomquist, Head of the Department of Russian Works of Art, narrated two 2014 videos with Fabergé auction highlights – a gem-set silver casket based on the Pushkin’s epic poem Ruslan and Ludmila and three imperial gifts.

December 2, 2015 Bonhams London

The Russian Sale includes a Fabergé hardstone pin tray discussed in the feature story above.

The Readers Forum of the Fabergé Research Newsletter continues to elicit interesting challenges. In the Winter 2014 edition Tatiana Muntian’s discovery of previously unknown costs for “Fabergé Easter Eggs for 1912, 1914, and 1915”, and a chart compiled by Riana Benko ranking the “Cost of Easter Eggs, 1900-1915” were published. Two readers posed questions relative to the data presented.

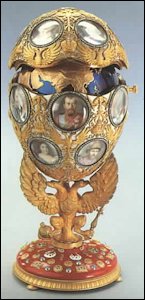

If this truly specific figure — right down to the 50 kopecks — is correct, then (given Muntian’s new figure for the Napoleonic Egg) the Tsesarevich Egg cost 28,597 roubles, 50 kopecks. This would not surprise, given the number of diamonds studded on it — and the very subject of the item — the Tsesarevich, the heir to the throne, so precious to Alexandra Feodorovna and Nicholas II. Armand Hammer, admittedly never noted for accuracy, did say it was worth 100,000 rubles, again probably because of the diamonds.

It would make the Tsesarevich Egg the most expensive egg, certainly more than the Mosaic Egg. While there is incredible workmanship in the Mosaic Egg, most of the gems are very small and not especially valuable. And the value of the labor in making it, may not have surpassed the value of the diamonds of the Tsesarevich Egg. Remember the politics involved, namely, that a female could not ascend to the throne. The Tsesarevich Egg would surely surpass the Mosaic in value, politically as well as in hard cash.

I would dismiss, out of hand the cost of the Tsesarevich Egg given in the Winter 2014 chart as 15,800 r. How could this be worth such a paltry sum when the virtually gemless Napoleonic Egg cost 22,300. Again, remember the politics involved …

Using internet resources two simplified comparisons can be made:

- Average Russian worker’s annual salary in 1885 was circa 30.5 r. The 1885 First Hen Egg by Fabergé cost 4151 r., or an equivalent of 136 years of average earnings. The cost of the 1913 Romanov Tercentenary Egg at 21,300 r. compared to the annual average salary (37.5 r.) equates to 568 years for one egg!

- In contrast, the annual income of an aristocratic nobleman was about 6,000 r., or more than the price of one egg for the years 1890-1895.

| CHART 1 | ||

|---|---|---|

| AVERAGE ANNUAL SALARIES IN TSARIST RUSSIA AND THE USSR |

||

| YEAR | AVERAGE SALARY IN RUBLES | AVERAGE SALARY IN KILOGRAMS OF POTATOES |

| 1880 | 30.38 | 1529.00 |

| 1890 | 30.63 | 1531.20 |

| 1897 | 31.40 | 1029.50 |

| 1900 | 33.04 | 1083.27 |

| 1905 | 33.78 | 1107.54 |

| 1909 | 35.71 | 1170.80 |

| 1913 | 37.50 | 1229.50 |

| 1917 (OCT) | 243.75 | |

| 1918 (END) | 600.00 | |

| CHART 2 | ||

|---|---|---|

| DOLLAR AND RUBLE VALUES | ||

| YEAR(S) | DOLLARS PER RUBLE | RUBLES PER DOLLAR |

| 1834-1896 | 0.77 | 1.3 |

| 1897 | 0.51533 | 1.94 |

| 1916 | 0.15 | 6.7 |

| 1917 | 0.09 | 11 |

| 1918 | 0.032 | 31.25 |

| 1919 | 0.0138 | 72.46 |

| 1920 | 0.0039 | 256 |

| 1921 | 0.00072 | 1389 |

| 1922 | 0.00048 | 2083 |

| 1923 | 0.000000425 | 2 352 941 |

| 1924 | 0.45 | 2.22 |

Fabergé, Tatiana, Proler, Lynette G., and Valentin V. Skurlov, Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs, 1997.

Lowes, Will, and Christel Ludewig McCanless, Fabergé Eggs: A Retrospective Encyclopedia, 2001. Updates for the encyclopedia entitled Fabergé Imperial Egg Chronology are being published on the Fabergé Research Site.

Zimin, Igor Viktorovich, and Alexander Sokolov Rostislavovich, Jewelry Treasures of the Russian Imperial Court (ювелирные сокровища российского императорского двора), 2012. In Russian.

Fabergé Research Newsletter, Winter 2014 and Summer 2015.

| TABLE I | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COMPARATIVE COST OF 50 IMPERIAL EASTER EGGS BY FABERGÉ | ||||||

| EASTER EGG NAME | YEAR MADE | GIFT FOR MARIE OR ALEXANDRA | RUBLES (r.) | $ VALUE IN YEAR MADE DIVIDE RUBLES BY 1.3 = $ | $ VALUE IN 2014 SOURCE |

|

| 1. | FIRST HEN EGG | 1885 | MF | 4 151 | 3 193 | 82 857 |

| 2. | HEN EGG WITH SAPPHIRE PENDANT | 1886 | MF | 2 986 | 2 297 | 59 606 |

| 3. | THIRD IMPERIAL EGG | 1887 | MF | 2 160 | 1 662 | 43 128 |

| 4. | CHERUB EGG WITH CHARIOT | 1888 | MF | 2 100 | 1 615 | 41 908 |

| 5. | NÉCESSAIRE EGG | 1889 | MF | 1 900 | 1 469 | 38 120 |

| 6. | DANISH PALACES EGG | 1890 | MF | 4 260 | 3 277 | 85 037 |

| 7. | MEMORY OF AZOV EGG | 1891 | MF | 4 500 | 3 462 | 89 837 |

| 8. | DIAMOND TRELLIS EGG | 1892 | MF | 4 750 | 3 654 | 94 819 |

| 9. | CAUCASUS EGG | 1893 | MF | 5 200 | 4 000 | 103 798 |

| 10. | RENAISSANCE EGG | 1894 | MF | 4 750 | 3 654 | 98 463 |

| 11. | ROSEBUD EGG | 1895 | AF | 3 250 | 2 500 | 70 027 |

| 12. | BLUE SERPENT CLOCK EGG | 1895 | MF | 4 500 | 3 462 | 96 974 |

| 13. | REVOLVING MINIATURES EGG | 1896 | AF | 6 750 | 5 1992 | 145 433 |

| 14. | ALEXANDER III PORTRAITS EGG | 1896 | MF | 3 575 | 2 750 | 77 030 |

| DIVIDE RUBLES BY 1.94 = $ | ||||||

| 15. | CORONATION EGG | 1897 | AF | 5 500 | 2 835 | 79 411 |

| 16. | MAUVE EGG WITH THREE MINIATURES | 1897 | MF | 3 250 | 1 675 | 46 918 |

| 17. | LILIES OF THE VALLEY EGG | 1898 | AF | 6 700 | 3 454 | 96 750 |

| 18. | PELICAN EGG | 1898 | MF | 3 600 | 1 856 | 51 988 |

| 19. | MADONNA LILY CLOCK EGG | 1899 | AF | 6 750 | 3 479 | 97 450 |

| 20. | PANSY EGG | 1899 | MF | 5 600 | 2 887 | 80 868 |

| 21. | TRANS-SIBERIAN RAILWAY EGG | 1900 | AF | 7 000 | 3 608 | 101 063 |

| 22. | CUCKOO CLOCK EGG | 1900 | MF | 6 500 | 3 351 | 93 865 |

| 23. | FLOWER BASKET EGG | 1901 | AF | 6 850 | 3 531 | 98 907 |

| 24. | GATCHINA PALACE EGG | 1901 | MF | 5 000 | 2 577 | 72 184 |

| 25. | CLOVER LEAF EGG | 1902 | AF | 8 750 | 4 510 | 121 471 |

| 26. | EMPIRE NEPHRITE EGG | 1902 | MF | 6 000 | 3 093 | 83 306 |

| 27. | PETER THE GREAT EGG | 1903 | AF | 9 760 | 5 031 | 130 542 |

| 28. | ROYAL DANISH EGG | 1903 | MF | 7 535 | 3 884 | 100 780 |

| 29. | MOSCOW KREMLIN EGG | 1906 | AF | 11 800 | 6 082 | 157 813 |

| 30. | SWAN EGG | 1906 | MF | 7 200 | 3 711 | 96 291 |

| 31. | ROSE TRELLIS EGG | 1907 | AF | 8 300 | 4 278 | 107 043 |

| 32. | LOVE TROPHIES EGG | 1907 | MF | 9 700 | 5 000 | 125 109 |

| 33. | ALEXANDER PALACE EGG | 1908 | AF | 12 300 | 6 340 | 164 562 |

| 34. | PEACOCK EGG | 1908 | MF | 8 300 | 4 278 | 111 041 |

| 35. | STANDART EGG | 1909 | AF | 12 400 | 6 392 | 165 912 |

| 36. | ALEXANDER III COMMEMORATIVE EGG | 1909 | MF | 11 200 | 5 773 | 149 845 |

| 37. | COLONNADE EGG | 1910 | AF | 11 600 | 5 979 | 149 655 |

| 38. | ALEXANDER III EQUESTRIAN EGG | 1910 | MF | 14 700 | 7 577 | 189 652 |

| 39. | FIFTEENTH ANNIVERSARY EGG | 1911 | AF | 16 600 | 8 557 | 214 183 |

| 40. | BAY TREE EGG | 1911 | MF | 12 800 | 6 598 | 165 149 |

| 41. | TSESAREVICH EGG | 1912 | AF | 28 597 | 14 741 | 356 147 |

| 42. | NAPOLEONIC EGG | 1912 | MF | 22 300 | 11 495 | 277 723 |

| 43. | ROMANOV TERCENTENARY EGG | 1913 | AF | 21 300 | 10 979 | 259 039 |

| 44. | WINTER EGG | 1913 | MF | 24 600 | 12 680 | 299 173 |

| 45. | MOSAIC EGG | 1914 | AF | 28 300 | 14 588 | 339 773 |

| 46. | CATHERINE THE GREAT EGG | 1914 | MF | 26 800 | 13 814 | 321 746 |

| 47. | RED CROSS TRIPTYCH EGG | 1915 | AF | 3 600 | 1 856 | 42 801 |

| 48. | RED CROSS PORTRAITS EGG | 1915 | MF | 3 875 | 1 997 | 46 052 |

| DIVIDE RUBLES BY 6.7 = $ | ||||||

| 49. | STEEL MILITARY EGG | 1916 | AF | COMBINED COST 13 347 | COMBINED COST 1 992 | COMBINED COST 42 692 |

| 50. | ORDER OF SAINT GEORGE EGG | 1916 | MF | |||

| TOTAL VALUE OF 50 IMPERIAL EGGS: | 453 246 r. | $242 665 | $6 163 941 | |||

- Maria Feodorovna received 30 Fabergé Easter eggs valued at 230,465 r./$127,737, or $3,244,613 in 2014.

- Alexandra Feodorovna received 20 Fabergé Easter eggs, valued at 222,780 r./$114,928, or $2,919,328 in 2014.

1912 Tsesarevich Egg (28,597 r.) Pratt Collection, Richmond, Virginia

1914 Mosaic Egg (28,300 r.) Royal Collection

of Queen Elizabeth II, UK

1914 Catherine the Great Egg

(26,800 r.) Hillwood Estate,

Museum and Gardens,

Washington, DC

1913 Winter Egg (24,600 r.) Private Collection

1912 Napoleonic Egg (22,300 r.) Gray Collection, New Orleans, Louisiana

1913 Romanov Tercentenary

Egg (21,300 r.) Kremlin

Armoury Collection,

Moscow

| TABLE II | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RANKING OF 50 FABERGÉ IMPERIAL EASTER EGGS BY 2014 DOLLAR VALUES | ||||||

| EASTER EGG NAME | YEAR MADE | GIFT FOR MARIE OR ALEXANDRA | RUBLES (r.) | $ VALUE IN YEAR MADE | $ VALUE IN 2014 SOURCE |

|

| 1. | TSESAREVICH EGG | 1912 | AF | 28 597 | 14 471 | 356 147 |

| 2. | MOSAIC EGG | 1914 | AF | 28 300 | 14 588 | 339 773 |

| 3. | CATHERINE THE GREAT EGG | 1914 | MF | 26 800 | 13 814 | 321 746 |

| 4. | WINTER EGG | 1913 | MF | 24 600 | 12 680 | 299 173 |

| 5. | NAPOLEONIC EGG | 1912 | MF | 22 300 | 11 495 | 277 723 |

| 6. | ROMANOV TERCENTENARY EGG | 1913 | AF | 21 300 | 10 979 | 259 039 |

| 7. | FIFTEENTH ANNIVERSARY EGG | 1911 | AF | 16 600 | 8 557 | 214 183 |

| 8. | ALEXANDER III EQUESTRIAN EGG | 1910 | MF | 14 700 | 5 773 | 189 652 |

| 9. | STANDART EGG | 1909 | AF | 12 400 | 6 392 | 165 912 |

| 10. | BAY TREE EGG | 1911 | MF | 12 800 | 6 598 | 165 149 |

| 11. | ALEXANDER PALACE EGG | 1908 | AF | 12 300 | 6 340 | 164 562 |

| 12. | MOSCOW KREMLIN EGG | 1906 | AF | 11 800 | 6 082 | 157 813 |

| 13. | ALEXANDER III COMMEMORATIVE EGG | 1909 | MF | 11 200 | 5 773 | 149 845 |

| 14. | COLONNADE EGG | 1910 | AF | 11 600 | 5 979 | 149 655 |

| 15. | REVOLVING MINIATURES EGG | 1896 | AF | 6 750 | 5 192 | 145 433 |

| 16. | PETER THE GREAT EGG | 1903 | AF | 9 760 | 5 031 | 130 542 |

| 17. | LOVE TROPHIES EGG | 1907 | MF | 9 700 | 5 000 | 125 109 |

| 18. | CLOVER LEAF EGG | 1902 | AF | 8 750 | 4 510 | 121 471 |

| 19. | PEACOCK EGG | 1908 | MF | 8 300 | 4 278 | 111 041 |

| 20. | ROSE TRELLIS EGG | 1907 | AF | 8 300 | 4 278 | 107 043 |

| 21. | CAUCASUS EGG | 1893 | MF | 5 200 | 4 000 | 103 798 |

| 22. | TRANS-SIBERIAN RAILWAY EGG | 1900 | AF | 7 000 | 3 608 | 101 063 |

| 23. | ROYAL DANISH EGG | 1903 | MF | 7 535 | 3 884 | 100 780 |

| 24. | FLOWER BASKET EGG | 1901 | AF | 6 850 | 3 531 | 98 907 |

| 25. | RENAISSANCE EGG | 1895 | MF | 4 750 | 3 654 | 98 463 |

| 26. | MADONNA LILY CLOCK EGG | 1899 | AF | 6 750 | 3 479 | 97 450 |

| 27. | BLUE SERPENT CLOCK EGG | 1895 | MF | 4 500 | 3 462 | 96 974 |

| 28. | LILIES OF THE VALLEY EGG | 1898 | AF | 6 700 | 3 454 | 96 750 |

| 29. | SWAN EGG | 1906 | MF | 7 200 | 3 711 | 96 291 |

| 30. | DIAMOND TRELLIS EGG | 1892 | MF | 4 750 | 3 654 | 94 819 |

| 31. | CUCKOO CLOCK EGG | 1900 | MF | 6 500 | 3 351 | 93 865 |

| 32. | MEMORY OF AZOV EGG | 1891 | MF | 4 500 | 3 462 | 89 837 |

| 33. | DANISH PALACES EGG | 1890 | MF | 4 260 | 3 277 | 85 037 |

| 34. | EMPIRE NEPHRITE EGG | 1902 | MF | 6 000 | 3 093 | 83 306 |

| 35. | FIRST HEN EGG | 1885 | MF | 4 151 | 3 193 | 82 857 |

| 36. | PANSY EGG | 1899 | MF | 5 600 | 2 887 | 80 868 |

| 37. | CORONATION EGG | 1897 | AF | 5 500 | 2 835 | 79 411 |

| 38. | ALEXANDER III PORTRAITS EGG | 1896 | MF | 3 575 | 2 750 | 77 030 |

| 39. | GATCHINA PALACE EGG | 1901 | MF | 5 000 | 2 577 | 72 184 |

| 40. | ROSEBUD EGG | 1895 | AF | 3 250 | 2 500 | 70 027 |

| 41. | HEN EGG WITH SAPPHIRE PENDANT | 1886 | MF | 2 986 | 2 297 | 59 606 |

| 42. | PELICAN EGG | 1898 | MF | 3 600 | 1 856 | 51 988 |

| 43. | MAUVE EGG WITH THREE MINIATURES | 1897 | MF | 3 250 | 1 675 | 46 918 |

| 44. | RED CROSS PORTRAITS EGG | 1915 | MF | 3 875 | 1 997 | 46 052 |

| 45. | THIRD IMPERIAL EGG | 1887 | MF | 2 160 | 1 662 | 43 128 |

| 46. | RED CROSS TRIPTYCH EGG | 1915 | AF | 3 600 | 1 856 | 42 801 |

| 47. | CHERUB EGG WITH CHARIOT | 1888 | MF | 2 100 | 1 615 | 41 908 |

| 48. | NÉCESSAIRE EGG | 1889 | MF | 1 900 | 1 469 | 38 120 |

| 49. | STEEL MILITARY EGG | 1916 | AF | COMBINED COST 13 347 | COMBINED COST 1 992 | COMBINED COST 42 692 |

| 50. | ORDER OF SAINT GEORGE EGG | 1916 | MF | |||

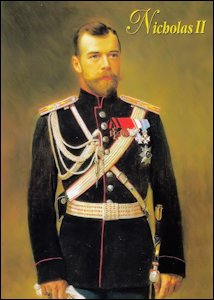

- Nicholas II, the last Russian Emperor was the fifth wealthiest man in the world. In 1917, his wealth was estimated at some $900 million, close to $16.5 billion in 2014 values.

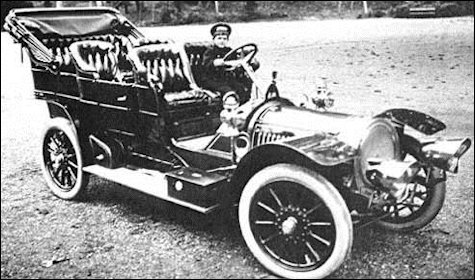

Tsesarevich Alexei in a French 1909 Delaunay-Belleville, Nicholas II’s Favorite Car

(Illustration 1-3, Wiki)

1897 Coronation Egg

(Courtesy Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg)

- 1905 Emperor Nicholas II bought his first car a cost of 18,400 r./$14,154 ($367,262). A year later Fabergé made the Moscow Kremlin Egg for Alexandra Feodorovna and the Swan Egg for Marie Feodorovna, costing a total of 19,000 r., or as much as the Emperor’s first car.

- 1909 Nicholas II purchased another new car costing ca. 16,000 r./$12,308 ($319,468 in 2014). Fabergé’s made the Standart Egg for the Emperor’s wife and the Alexander III Commemorative Egg for his mother that year, totaling 23,600 r., or $12,165 ($315,757 in 2014).

- Today the 1897 Coronation Egg in the collection of the Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia, is probably the most recognized egg of the Imperial Easter Eggs by Fabergé. It ranks only no. 37 in 2014 dollar values of $79,411.

- The 1913 Winter Egg (ranked the 4th most expensive egg) sold at auction in 1994 for ca. $5.6 million, and in 2002 for ca. $9.6 million. 2014 values for Maria Feodorovna’s 30 eggs total ca. $3.2 million, and Alexandra’s 20 eggs $2.9 million.

Ms. Benko thanks Prof. Igor Zimin and Dr. Valentin V. Skurlov for their assistance in the reviewing the tables. DeeAnn Hoff and George McCanless assisted in fact/figure-checking.

First Fabergé Imperial Egg and a Possible Prototype – Saxon Royal Egg, Collection

of Augustus the Strong (1670-1733)

(Courtesy Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia; Géza von Habsburg)

However, Fabergé, Proler, & Skurlov reported in Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs (London, 1997), an exchange of letters between Tsar Alexander III and his brother, the Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich, which settles the issue beyond doubt.

In a letter dated March 21 (OS), 1885, Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich advises Alexander III that:

The letter goes on to describe in detail how the egg and its various surprises should be correctly opened. Alexander III replied the same day from Gatchina Palace:

Obviously the tsarina was delighted, for a tradition had begun that would become the zenith of the decorative arts in the Western world. While these letters explain when the tradition started, the reason why is still not known. The last sentence of the tsar’s letter suggests there was a specific reason for the gift.

H. C. Bainbridge was adamant that Fabergé approached the tsar with the idea (Presentation of Imperial Russian Easter Gifts by Carl Fabergé (New York), and Hammer Galleries exhibition catalog, September 8 – November 30, 1939). Mogens Bencard in the exhibition catalog, Maria Feodorovna, Empress of Russia (Copenhagen, 1997), believes there was a meeting between Fabergé and the tsarina (and not the tsar) before the egg was made. Suggestions have been made that Armand Hammer took the Tsar Imperial First Hen Egg out of Russia. Indeed, Hammer himself claimed to have done so. However, the egg Hammer purchased was sold to Matilda Geddings Gray and is still in the Gray Foundation Collection. It is not the egg sold at the Christie’s auction in London on March 15, 1934, which is the first Tsar Imperial egg. Further detail can be found under ‘Crown Egg’ in the first two citations listed above.

A. Kenneth Snowman pointed out a similar egg exists in the Danish Royal Collection, which may well have been known to Marie, formerly the Danish Princess Dagmar. Fabergé made a number of other eggs similar to the First Hen Egg. Géza von Habsburg in “Fabergé’s Imperial Eggs – Their Inspirations and Prototypes” (Fabergé Research Newsletter, Fall 2013) discusses several prototypes for this egg.

- March 24 (OS), 1885. Would have been presented to Marie Feodorovna, a gift from Alexander III; cost 4,151 rubles, 75 kopecks. Housed in the Anichkov Palace

- September 16-20 (OS), 1917. One of forty or so eggs sent to the Armoury Palace of the Kremlin in Moscow by the Kerensky Provisional Government for safekeeping

- ca. 1920s. Bought by dealer, Derek (Editor’s note: Frederick?) Berry, London, probably from Russian officials in Berlin or Paris

- March 15, 1934. Lot 55 sold by Christie’s (London) from the Derek (Editor’s note: Frederick?) Berry Collection, UK, for £85; $430, to Mr. R. Suenson-Taylor, UK

- June 1955. Owned by Lord Grantchester, barrister and financier. Sir Alfred Suenson-Taylor was created first Baron Grantchester, June 30, 1953

- 1961. Owned by Mamie Suenson-Taylor, Lady Grantchester, UK

- 1976. Owned by estate of Lord and Lady Grantchester. They died within months of each other

- Acquired by A La Vieille Russie, New York

- January 16, 1978. Sold by A La Vieille Russie, to Forbes Magazine Collection, New York for $126,250

- February 2004. Sold privately as part of the Forbes Magazine Collection, New York, to Viktor Vekselberg, Moscow, for just over $100 million, according to the purchaser

- November 19, 2013. Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

(Keefe, John W., Masterworks of Fabergé:

The Matilda Geddings Gray Foundation Collection, 2008, 88-89)

- Imperial yacht Polar Star

- Bernsdorff Palace, Copenhagen

- Kejserens Villa in Fredensborg Park

- Fredensborg Palace from the Marble Garden

- Schack Palace in the Amaliensborg Palace complex

- Kronborg Castle, Elsinore

- Two views of the Cottage Palace, Alexandreskii Park, Peterhof

- Gatchina Palace, near St. Petersburg

- Imperial yacht Tsarevna

The egg retains its original velvet case; the stand is modern.

And yet, existing literature dated the egg at 1895, probably because that date had been written in ink on the velvet case. We know from the memoirs of François Birbaum in von Habsburg & Lopato, Fabergé: Imperial Jeweller (London, 1993) Tsar Alexander III had laid down broad rules relating to the eggs: that the egg shapes continue, but that there be no repetitions. With this in mind, there surely cannot be two eggs in pink enamel in the Louis XVI style, especially within five years of each other. The date 1895 was probably written on the egg’s case during the 1922 inventory of confiscated Imperial treasure. It seems the real 1895 gift, the Blue Serpent Clock Egg, was not among the eggs listed in this inventory or that of 1917, and an assumption regarding the egg was made at that time. Proof that the Danish Palaces Egg was made before 1895 is available from a list made when the Imperial couple traveled, taking with them items from Gatchina Palace: “Egg consisting of 10 pieces (small folding screen). His Majesty took it to Petersburg on 31 December (OS), 1891, and returned it on 28 March (OS), 1892.” (Fabergé, Proler, & Skurlov, Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs, London, 1997) It is definitely identified in the 1917 inventory of confiscated Imperial treasure and possibly in the inventory made in 1922.

A 1932 scrapbook belonging to the Hammer Galleries further confuses the history of this egg by describing the egg as having twelve panels, not ten, and a cut and re-glued photograph shows the egg sitting in a wooden box, not in the original velvet case (Hammer Galleries Book I, 1932). The twelve-panel description is repeated in Compleat [sic] Collector, April 1943. To complicate matters further, the Hammer Galleries exhibition of 1939 has a photograph showing only ten frames, and showing the frames as the surprise for this egg. Despite all these varying descriptions, it now seems clear only ten miniatures ever existed. The scenes depicted on the miniatures were places familiar to Marie Feodorovna, and the yachts she used to travel in. For many years, the third panel of the Egg was wrongly identified as the estate of Hvidøre. Russian scholars Galina Korneva and Tatiana Cheboksarova identified in their publication, Empress Maria Feodorovna’s Favorite Residences in Russia and in Denmark (St. Petersburg, 2006) the palaces in the order listed above. Danish Fabergé enthusiast Christian Steener Eriksen had also noticed Marie Feodorovna and her sister Queen Alexandra of Great Britain had not bought the property until 1906, so a miniature of the residence could not have been included in an Easter gift made for 1890. On September 1, 1889, the New York Times reported:

In 2008 research by Annemiek Wintraecken and Steener Eriksen they found other documentation in which Alexander III expressed a wish in September 1885 to have his own residence in Fredensborg. Petrel’s Nest, a property in the palace gardens was bought, refurbished, and opened with a tea-party on October 1, 1889. Marie Feodorovna baptized the building and described it as ‘Our dear miniature Gatchina’. The house became known as the Kejserens Villa (Emperor’s Villa). In October 1980, the Egg was stolen while on exhibition at the Paine Art Center and Arboretum in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. It was recovered soon after, following a high-speed police pursuit, during which it was jettisoned with two other Tsar Imperial eggs, the 1893 Caucasus Egg and the 1912 Napoleonic Egg.

- March 30 (OS), 1890. Presented to Alexander III

- April 1 (OS), 1890. Would have been presented to Marie Feodorovna, a gift from Alexander III; cost 4,260 silver rubles

- January 31 (OS), 1893. Housed at the Gatchina Palace

- September 16-20 (OS), 1917. One of forty or so eggs sent to the Armoury Palace of the Kremlin in Moscow by the Kerensky Provisional Government for safekeeping

- February-March 1922. Probably transferred to the Sovnarkom, the Council of People’s Commissars

- June-July 1927. One of eight eggs returned by the Moscow Jewelers’ Union to the Armoury; given inventory no. 17553

- April 30, 1930. One of twelve eggs selected for export sale

- June 21, 1930. Transferred from the Armoury to the Antikvariat (Trade Department)

- 1930. One of ten Imperial eggs sold by the Antikvariat, Moscow, to Hammer Galleries, New York, for 1,500 rubles (ca. $750)

- ca. October 1935. Advertised by Hammer Galleries for $25,000

- February 1936. Advertised by Hammer Galleries

- November 1937-1953. Owned by Mr. & Mrs. Nicholas H. Ludwig, New York

- 1962. Private collection, United States

- June 8, 1971. Collection of the late Matilda Geddings Gray, oil heiress, Lake Charles and New Orleans, Louisiana

- 1972. Matilda Geddings Gray Foundation, New Orleans, Louisiana

(Courtesy Armoury Museum, Moscow)

A second blow was parried by Prince George of Greece, the second son of King George I of Greece, who fended off the attack with his cane. George, a boyhood friend of Nicholas, had joined the eastern adventure in Athens, where the Russian princes stopped before traveling east. Nicholas told Marie Feodorovna: “I stopped and turned round and to see dear Georgie about ten paces from me, with the policeman, whom he had knocked to the ground with one blow of his cane, laying at his feet. Had Georgie not been in the rickshaw behind me, dearest Mama, perhaps I would never have seen you again!” Nicholas was left permanently scarred both physically and mentally, and the incident poisoned his view of the Japanese, whom he described in private as “monkeys.” The Ōtsu incident probably played a role in the Tsar’s ill-fated decision to go to war against the Japanese 13 years later. Blood from a handkerchief used to staunch the Tsesarevich’s wound was used 100 years later in the earliest DNA testing done to positively identify the body of Nicholas II.

Grand Duke George’s lung condition appeared to worsen, and he had already returned to Russia before Nicholas arrived in Japan. Tatiana Muntian has observed that “For people familiar with the unfortunate journey, the blood-red drops in the heliotrope and the bright red ruby of the knob had a sinister meaning”. (Muntian, et al. World of Fabergé, Moscow, 1996) Seven years later, she saw further symbolism in the egg:

The cruiser In Memory of the Azov was named in honor of the Azov, the first Russian battleship to be awarded the St. George flag. It won the honor for its role in the Battle of Navarino in 1827. A letter written by Eugène Fabergé on June 5, 1934, says the miniature was made “by the old (Editor’s note: August) Holmström, who especially put all his art into making the tiny ship as natural as possible so that the guns were movable and all the rigging exactly copied. Even the chains of the anchors were movable.” (Fabergé, Proler, & Skurlov, Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs, London, 1997)

As stated above, this was one of the Tsar Imperial eggs which traveled from St. Petersburg and was returned to Gatchina Palace. In 1900, it was exhibited at the Exposition Internationale Universelle in Paris in 1900, along with the 1898 Lilies of the Valley, the 1899 Pansy, the 1897 Coronation, the 1900 Trans-Siberian Railway Eggs, and possibly the 1890 Danish Palaces Egg. But the 1891 Memory of Azov Egg did not impress the French judge, René Chanteclair:

Other judges, including Victor Champier and the noted enameller Louis Houillon, were more enthusiastic about Fabergé’s work. In any event, the Exposition brought Fabergé and his work to the notice of the world.

The Memory of Azov Egg is readily identifiable in both the 1917 and 1922 inventories of confiscated Imperial treasure. An expert valuation was made of this egg in 1927. Found by Fabergé, Proler, & Skurlov, the valuation noted the mast was damaged, one rose-cut diamond was missing, and there was “a noticeable crack in the jasper.” The egg’s worth was assessed at 8,880 rubles. With the 1902 Clover Leaf and 1906 Moscow Kremlin Eggs, this egg was scheduled for sale to the West. They were returned to the Armoury, following protests from workers and management within the Armoury.

- April 21 (OS), 1891. Would have been presented to Marie Feodorovna, a gift from Alexander III; cost 4,500 silver rubles

- November 27 (OS), 1891. Housed at the Gatchina Palace

- September 16-20 (OS), 1917. One of forty or so eggs sent to the Armoury Palace of the Kremlin in Moscow by the Kerensky Provisional Government for safekeeping

- February-March 1922. Transferred to the Sovnarkom, the Council of People’s Commissars

- June 17, 1927. One of sixteen eggs transferred from the Foreign Currency Fund of the Narkomfin (Finance Ministry) to the Armoury; given inventory no. 17536

- 1933. Was to be offered for sale at 20,000 rubles, but retained in the Armoury Museum, Moscow

Diamond Trellis Egg in Maria Feodorovna’s

Exhibit Case, 1902 von Dervis Mansion Venue,

St. Petersburg, Russia

(Archival Photograph)

Egg Missing Its Surprise with Putti

Base, Sotheby’s London, 1960

(Archival Photograph)

Egg Missing Its Surprise and Base

(Courtesy McFerrin Collection)

“The Egg is lined with white satin with a space for the figure of an elephant and a key for winding 1 Ivory figure of an elephant, clockwork, with a small gold tower; partly enameled and decorated with rose-cut diamonds, on its back; the sides of the figure bearing gold decorations in the form of two crosses, each with five precious stones. The elephant’s forehead is decorated with the same kind of stone. The tusks, trunk and harness are decorated with small rose-cut diamonds, and a black mahout is seated on its head.” (Fabergé, Proler, Skurlov, Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs, London, 1997)

The elephant mentioned was the surprise inside the egg. At present, the egg exists alone in the Dorothy and Artie McFerrin Collection. The pedestal is either lost or survives elsewhere. The pedestal, but not the surprise, was still with the egg when it was sold by Sotheby’s London, on December 5, 1960. The catalog description includes the line …supported on the backs of three silver putti who are seated on a grassy mound ¦ There is an accompanying illustration of the egg with its pedestal of three silver putti. Toby Faber in Fabergé Eggs: The Extraordinary Story of the Masterpieces that Outlived an Empire (London, 2008) says the Diamond Trellis Egg was …subsequently separated from its genuine stand by Emanuel Snowman in [the] mistaken belief that this was a later addition. The elephant appears on the coat of arms of the Danish Royal family, and Marie, of course, was a Danish princess. The reference to the elephant being …clockwork suggests it was the first automaton used by Fabergé in a Tsar Imperial egg.

On October 10, 2015, the Curator of Queen Elizabeth II’s Fabergé collection, Caroline de Guitaut confirmed to the Lapidary Art Symposium at the St. Petersburg Fabergé Museum that an ivory automaton elephant in the Royal Collection matches the known descriptions of the Diamond Trellis Egg’s surprise. In consultation with Dorothy and Artie McFerrin, it was determined the miniature elephant fits the Diamond Trellis Egg. Ms. de Guitaut explained: “A fragment of the elephant’s turret was lost. It seems it had just fallen off due to the aged metal. Yet as a result, it was possible to look into the foundation of the figure. When we removed the top part of the turret, my heart nearly stopped beating: It contained the Fabergé hallmark! That is how we found the proof of the discovery’s authenticity.” She continued: “The newly discovered automaton surprise is almost identical to the badge of the Danish Order of the Elephant, the most senior order of chivalry in Denmark, except that it is made of ivory rather than white enamel and that it incorporates a mechanism. The elephant is wound with a watch key through a hole hidden underneath the diamond cross on one side of the elephant. It walks tentatively on ratcheted wheels and lifts its head up and down.”

Apart from being the first known automaton surprise used in a Tsar Imperial Easter Egg, this mechanical elephant is seemingly among the first automata made by Fabergé. In comparison with the mechanical devices used in the 1906 Swan and 1908 Peacock Eggs, this automaton is almost primitive. But it is yet another example of Fabergé and his workforce trying something new and which, over time would be extensively and exquisitely refined. The automaton elephant this theme would be repeated eight years later in the 1900 Pine Cone Egg made for Barbara Kelch, neé Bazanova ,was the daughter of an extremely wealthy Moscow merchant family. In 1894, she married Alexander Ferdinandovich Kelch, a titled gold magnate and industrialist. In the years from 1898 to 1904, Kelch presented to his wife eggs quite on a par with their Imperial counterparts.

Tatiana Muntian’s research in von Solodkoff, Fabergé: Juwelier des Zarenhofes (Hamburg, 1995) quotes the 1917 inventory of confiscated Imperial treasure as including the …brilliant grill (-work/trellis) egg of 1892 – an egg of nephrite in gold setting, with a brilliant-covered net, base of nephrite with three silver putti. The 1922 inventory of confiscated Imperial treasure includes as a separate entry, …Ivory model of an elephant in gold setting with rose-cut diamonds and diamonds. According to Caroline de Guitaut, the newly discovered automaton surprise is almost identical to the badge of the Danish Order of the Elephant, the most senior order of chivalry in Denmark, except it is made of ivory rather than white enamel and incorporates a mechanism. The elephant is wound with a watch key through a hole hidden underneath the diamond cross on one side of the elephant. It walks on ratcheted wheels and lifts its head up and down.

It is possible the Diamond Trellis Egg is one of two Fabergé eggs referred to in an article by Alexander Mosyakin, …The Sale: Our Country’s Great Loss, in the Moscow newspaper Ogonyok, No. 7, February 1989. Mosyakin refers to two eggs both of …jadeite (sic) with dozens of brilliants being sold for $450 each. This sparse comment could be a rough description of the Diamond Trellis Egg. The description probably should refer to rose-cut diamonds, not brilliants. However, it is difficult to see how an egg with …dozens of brilliants could be worth only $450.

- April 5 (OS), 1892. Would have been presented to Marie Feodorovna, a gift from Alexander III; cost 4,750 silver rubles

- 1893? Housed at the Gatchina Palace

- September 16-20 (OS), 1917. One of forty or so eggs sent to the Armoury Palace of the Kremlin in Moscow by the Kerensky Provisional Government for safekeeping

- February-March 1922. Transferred to the Sovnarkom, the Council of People’s Commissars

- ca. 1927. Probably sold to Michel Norman of the Paris-based Australian Pearl Company or his associate Norman Weisz, by officials of the Antikvariat (Trade Department)

- Sold to Emanuel Snowman of Wartski, London

- 1929. Transferred from Wartski, Llandudno, Wales to Wartski, London, having been purchased for £125

- October 19, 1929. Bought from Wartski by T. B. Kitson, UK for £260

- December 5, 1960. Lot 92 sold by Sotheby’s London from the Collection of the late T. B. Kitson, UK, to buyer’s agent, Drager, for £2,400, $6744

- 1962-77. Private collection, UK

- May 1983. Private collection, London

- 1985. Private collection, US

- April 11, 2003. Lot 101 offered by Christie’s New York from a private American collection, passed at $1,300,000

- 2012. Dorothy & Artie McFerrin Collection, Houston Museum of Natural Science, Texas

Elephant Surprise:

- 1927-29: With Wartski; likely purchased separately from the Egg

- 1935. Sold to King George V, London, and possibly a gift for Queen Mary

- 2015. The Royal Collection, London

LEFT EGG: 18th Century Casket by LeRoy | RIGHT EGG: Fabergé Renaissance Egg (Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia)

(LEFT PICTURE: Photograph © Géza von Habsburg | RIGHT PICTURE: Courtesy Green Vault, Dresden, Germany)

- April 17 (OS), 1894. Would have been presented to Marie Feodorovna, a gift from Alexander III; cost 4,750 silver rubles. Housed in the Anichkov Palace

- September 16-20 (OS), 1917. One of forty or so eggs sent to the Armoury Palace of the Kremlin in Moscow by the Kerensky Provisional Government for safekeeping

- February-March 1922. Probably transferred to the Sovnarkom, the Council of People’s Commissars

- June-July 1927. One of eight eggs returned by the Moscow Jewelers’ Union to the Armoury; given inventory no. 17552

- April 30, 1930. One of twelve eggs selected for export sale

- June 21, 1930. Transferred from the Armoury to the Antikvariat (Trade Department)

- 1930. One of ten Imperial eggs sold by the Antikvariat, Moscow, to Hammer Galleries, New York, for 1,000 rubles (ca. $500)

- May 1937. Advertised by Hammer Galleries

- November 1937-1947. Owned by Henry Talbot de Vere Clifton, millionaire landowner, sportsman, and poet, UK

- November 1949. Owned by Jack & Belle Linsky, stapler fortune, New York

- 1958. Sold by Jack & Belle Linsky to A La Vielle Russie, New York

- March 1959. Advertised by A La Vieille Russie, New York for $50,000

- May 1960. Advertised by A La Vieille Russie, New York

- 1962. Owned by Alexander Schaffer of A La Vieille Russie, New York

- June 1, 1966. Sold by A La Vieille Russie, New York to Forbes Magazine Collection for $78,750

- February 2004. Sold privately as part of the Forbes Magazine Collection, New York, to Viktor Vekselberg, Moscow, for just over $100 million, according to the purchaser

- November 19, 2013. Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Tsar Alexander III (1845-1894) and His Consort Marie Feodorovna (1847-1928)

(Wiki)

Tsar Nicholas II (1868-1918) and His Consort Alexandra Feodorovna (1872-1918)

(Source: Royal Russia News, Wiki)

| FAVORITE EGGS | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| (SHARED BY FABERGÉ ENTHUSIAST BOB DOMMETT FROM THE UK) | |||

| 1. | 1913 WINTER EGG | 6. | 1913 ROMANOV TERCENTENARY EGG |

| 2. | 1897 CORONATION EGG | 7. | 1902 CLOVER LEAF EGG |

| 3. | 1914 CATHERINE THE GREAT EGG | 8. | 1911 FIFTEENTH ANNIVERSARY EGG |

| 4. | 1898 LILIES OF THE VALLEY EGG | 9. | 1898 PELICAN EGG |

| 5. | 1914 MOSAIC EGG | 10. | 1900 CUCKOO CLOCK EGG |

| LOCATIONS OF THE 50 IMPERIAL FABERGÉ EGGS | ||

|---|---|---|

| (MORE DETAILS IN THE FABERGÉ IMPERIAL EGG CHRONOLOGY AND EXHIBITIONS WORLDWIDE) | ||

| RUSSIA | USA | EUROPE |

| KREMLIN ARMOURY MUSEUM, MOSCOW | VIRGINIA MUSEUM OF ARTS, RICHMOND LILLIAN THOMAS PRATT COLLECTION | ROYAL COLLECTION, QUEEN ELIZABETH II LONDON, UK |

| 1891 MEMORY OF AZOV EGG | 1896 REVOLVING MINIATURES EGG | 1901 FLOWER BASKET EGG |

| 1899 MADONNA LILY CLOCK EGG | 1898 PELICAN EGG | 1910 COLONNADE EGG |

| 1900 TRANS-SIBERIAN RAILWAY EGG | 1903 PETER THE GREAT EGG | 1914 MOSAIC EGG |

| 1902 CLOVER LEAF EGG | 1912 TSESAREVICH EGG | |

| 1906 MOSCOW KREMLIN EGG | 1915 RED CROSS PORTRAITS EGG | EDOUARD AND MAURICE SANDOZ FOUNDATION, LAUSANNE, SWITZERLAND |

| 1908 ALEXANDER PALACE EGG | 1906 SWAN EGG | |

| 1909 STANDART EGG | METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART, NY (LOAN EXHIBIT CLOSES NOV 2016) MATILDA GEDDINGS GRAY FOUNDATION | 1908 PEACOCK EGG |

| 1910 ALEXANDER III EQUESTRIAN EGG | 1890 DANISH PALACES EGG | |

| 1913 ROMANOV TERCENTENARY EGG | 1893 CAUCASUS EGG | PRINCE ALBERT II OF MONACO COLLECTION, MONTE CARLO |

| 1916 STEEL MILITARY EGG | 1912 NAPOLEONIC EGG | 1895 BLUE SERPENT CLOCK EGG |

| FABERGÉ MUSEUM, ST. PETERSBURG LINK OF TIMES COLLECTION | HILLWOOD ESTATE, MUSEUM & GARDENS, WASHINGTON, DC MARJORIE MERRIWEATHER POST COLLECTION | |

| 1885 FIRST HEN EGG | 1896 ALEXANDER III PORTRAITS EGG | |

| 1894 RENAISSANCE EGG | 1914 CATHERINE THE GREAT EGG | |

| 1895 ROSEBUD EGG | ||

| 1897 CORONATION EGG | WALTERS ART GALLERY, BALTIMORE MARYLAND HENRY WALTERS BEQUEST | |

| 1897 SURPRISE FROM MISSING MAUVE EGG WITH THREE MINIATURES (SCHOLARS DISAGREE, IF THIS IS THE SURPRISE FOR THE MISSING EGG) | 1901 GATCHINA PALACE EGG | |

| 1898 LILIES OF THE VALLEY EGG | 1907 ROSE TRELLIS EGG | |

| 1900 CUCKOO CLOCK EGG | CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART, OHIO INDIA EARLY MINSHALL COLLECTION | |

| 1911 BAY TREE EGG | 1915 RED CROSS TRIPTYCH EGG | |

| 1911 FIFTEENTH ANNIVERSARY EGG | ||

| 1916 ORDER OF SAINT GEORGE EGG | ||

| HOUSTON MUSEUM OF NATURAL SCIENCE, TEXAS (LOANED FROM THE DOROTHY AND ARTIE MCFERRIN COLLECTION) | ||

| FERSMAN MINERALOGICAL MUSEUM, MOSCOW | 1892 DIAMOND TRELLIS EGG | |

| 1917 BLUE TSESAREVICH EGG (UNFINISHED) | ||

| PRIVATE COLLECTIONS | |

|---|---|

| 1887 THIRD IMPERIAL EGG | 1907 LOVE TROPHIES EGG |

| 1899 PANSY EGG MATILDA GRAY STREAMS, NEW ORLEANS, LOUISIANA | 1913 WINTER EGG STATE OF QATAR |

| MISSING IMPERIAL EASTER EGGS | |

|---|---|

| 1886 HEN EGG WITH SAPPHIRE PENDANT | 1902 EMPIRE NEPHRITE EGG |

| 1888 CHERUB EGG WITH CHARIOT | 1903 ROYAL DANISH EGG |

| 1889 NÉCESSAIRE EGG | 1909 ALEXANDER III COMMEMORATIVE EGG |

| 1897 MAUVE EGG WITH THREE MINIATURES | |

In the history section of the Bolin website the similar paths the two companies took prior to 1917 are discussed. (Search term Fabergé only works with the accented é.)

The documentary, Fabergé. Lost and Found filmed in the Fabergé Museum in St. Petersburg, is narrated by Dr. Valentin V. Skurlov. Members of the Board of Directors of the private museum are also interviewed. (2014, 44 min., in Russian)

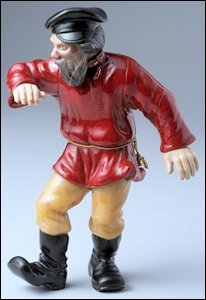

Dancing Mujik Purchased by Emporer

Nicholas II in December 1910 for 850 rubles

(Courtesy Fabergé Museum,

St. Petersburg, Russia)

Coffeepot from a Three-piece Set, Fedor

Rückert Workshop Marked Fabergé

(Courtesy Walters Art Museum)

Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

October, 8-10, 2015 International Museum Conference with the theme of Lapidary Art covered two main topics:

- History of Fabergé’s stone carvings with their present locations, problems of attribution and authentication, restoration and preservation

- Works of Carl Fabergé’s contemporary stone carvers and origin of their art, as well as their role and place in the world’s art history.

Caroline de Guitaut, Senior Curator of Decorative Arts, Royal Collection Trust, London, was the headline speaker for the event also open to the public. Her topic – “East and West: Russian Lapidary Art and the British Royal Collection” included the announcement that the missing elephant automaton surprise of the 1892 Diamond Trellis Egg was found. Presenters for the symposium are listed on the event program. An illustrated collection of reports based on the conference results is to be published.

Houston Museum of Natural Science, Texas

The Artie and Dorothy Fabergé exhibition will be continuing through 2016.

Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Maryland

The Jean Riddell Russian Enamels Collection was bequeathed to the Walters Art Museum in 2011. Many of the 260 pieces from the gift are accessible on the museum’s collections website. The museum staff continues the slow process of cleaning and conserving the pieces to mount an exhibition for the 100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution. The catalog for this exhibition is in the planning process and should be complete by early 2017. (Courtesy Dr. Robert M. Mintz, Walters Art Museum)

Gold, Asbestos, and Diamonds Dandelion Pin by Fabergé, ca. 1900

(Courtesy Wartski)

St. Petersburg Jeweler Alexander Edvard

Gustavovich Tillander (b. in Finland, 1837-1918)

Became a Goldsmith Master in 1860, Founded His

Company to Become One of the Established

Jewelers of St. Petersburg, Russia.

(Photograph Courtesy of

The Tillander Family Collection)

Geoffrey Munn, author of Wartski – The First One Hundred and Fifty Years, is featured in an interview with the Jewish Chronicle Online, August 28, 2015.

Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm, a recognized expert of pre-revolutionary St. Petersburg jewelry history, has been studying the diaries of Alexander Edvard Gustavovich Tillander, and Alexander Theodor Alexandrovich, her grandfather, both gentlemen in two generations were known as Alexander Tillander. The diaries offer a unique insight both into the professional and personal life of a St. Petersburg jeweler with a myriad of particulars from this fascinating world of craftsmen, collaborators and illustrious clients. On August 27, 2015, she lectured on this topic – “From St Petersburg to Helsinki. The Saga of the Tillander Family of Goldsmiths”- at the St. Petersburg Fabergé Museum. A book based on her research will be published in English and Russian in the near future.

A new trend in publishing is evolving to capture additional research and errata for collections and books published for Carl Fabergé’s decorative art objects:

- The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts has added to its website a segment called Updates to Fabergé Revealed (2010 exhibition and catalogue raisonné by Géza von Habsburg, et al. with the title Fabergé Revealed) containing two PDF links –

- Lowes, Will and Christel Ludewig McCanless, authors of Fabergé Eggs: A Retrospective Encyclopedia, 2001, are publishing their new research and updates for 50 Imperial Easter Eggs in the Fabergé Imperial Egg Chronology of the Fabergé Research Site.