Fall and Winter 2020

Ahtola-Moorhouse, Leena. Fabergé ja minä. Ulla Tillander-Godenhielmin elämä

Ahtola-Moorhouse, Leena. Fabergé ja minä. Ulla Tillander-Godenhielmin elämä

(Fabergé and Me. The Life of Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm) Published by Tammi, Helsinki, Finland, 2020

Master’s Mark AT Variations in the World of St. Petersburg’s Goldsmiths: Solving an Old Puzzle

By Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm (Finland)

Craftsmen in the gold- and silversmith trade learned their profession in accordance with a long-established system by fulfilling the requirements in three stages of training – apprentice, journeyman and master. A young boy (age 10-12 years) applied for the right to become an apprentice in a workshop owned by an authorized master gold- or silversmith. The Apprentice learned the trade step by step sitting next to an accomplished craftsman. The average time of apprenticeship was six years. After he passed the tests, and demonstrated an acceptable level of craftsmanship and technical knowledge of the craft, he became a Journeyman. To become a Master, a journeyman had to practice the craft for a minimum of three years, preferably with different authorized masters, pass the master’s test, and produce a master-piece. An object or a piece of jewelry in gold, or in case of a silversmith an object in silver, had to be approved by a council of appointed authorized master gold- or silversmiths. Three levels of schooling determined the hierarchy of the workshop. A workshop was headed by a master goldsmith, whose mark had been approved and registered with his local Assay Office. The mark became the official mark of the workshop. The master was either the owner of the workshop or appointed by the owner. In the latter case, his title was workmaster. The workbenches of a large workshop (like those in the Fabergé firm) were manned by both master goldsmiths and journeymen as well as apprentices.

A master goldsmith’s mark usually depicts the master’s initials. It serves as the main key for identifying an object made by him. Problems of identification arise, if there are several master goldsmiths with the same initials as was the case in St. Petersburg between the 1850’s and 1917 when nine St. Petersburg goldsmiths registered masters’ marks with the initials AT. Four of them are reviewed here with biographical data and a look at their production styles, and techniques. An effort is made to correct or clear-up some of the misconceptions and erroneous information accumulated over the years.

Master’s Mark AT Variations in the World of St. Petersburg’s Goldsmiths

Subcontractors with Various AT Marks Working for Retail Jewelers in Chronological Order

(Not Covered in this Essay)

-

Exact Mark Unknown August Tamlander (active 1857-?)

-

Exact Mark Unknown Andreas Turunen (active 1853-1873)

-

Exact Mark Unknown Alexander Tiitain (active 1870-1880)

-

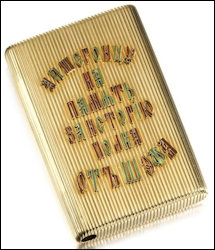

A. Tobinkov, workmaster of Nicholls & Plincke (active 1870-?)

A. Tobinkov, workmaster of Nicholls & Plincke (active 1870-?)

-

Albanus Toivanen (active 1898-1917)

Albanus Toivanen (active 1898-1917)

Of the four master goldsmiths marking their production with their initials, Alexander Treiden is discussed here at length, because he has not been as thoroughly researched as have the workmasters Alfred Thielemann, and the father and son team of Tillander. Treiden’s production has frequently been incorrectly attributed either to Tillander or Thielemann. The original German spelling of the name Treiden is used in this article instead of the Treyden often seen in English language publications.

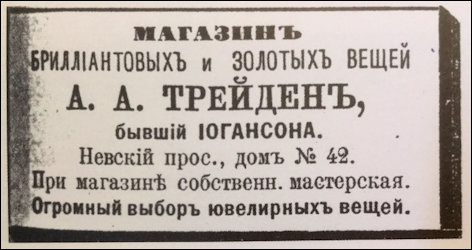

1. Letterhead of Court Jeweler Carl Hahn’s Shop Specializing in Diamond Jewelry and Goldsmiths’ Products (Courtesy Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm)

The beginning of the Alexander Treiden’s story relates to the Court Jeweler Carl Hahn (active 1873-1911), who belonged to the top tier of St. Petersburg’s jewelers, including the firms of Fabergé and Bolin. Hahn’s production consisted of diamond jewelry, an impressive number of jeweled presentation boxes for the Cabinet of His Imperial Majesty, diamond-set insignia of the Imperial Orders, diamond portraits, and maid-of-honor ciphers. In addition, the firm of Hahn produced a wide range of objects for sale in its own retail shop. The production was handled in two workshops – one headed by Carl Blank, and the other headed by Treiden. Both Blank and Treiden were master jewelers and owners of their workshops. They worked for Hahn under contract. In other words, Hahn operated on the same system as did Fabergé and many other St. Petersburg jewelers.

Carl Blank (active 1882-1917) was the head workmaster of the Court Jeweler Hahn. Blank specialized in making the official diamond-set insignia commissions, and produced one of Hahn’s most important Imperial assignments, the diamond crown of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna for the 1896 Coronation. In 1894, Blank was appointed Merchant of the Second Guild. In 1899, after the death of the founder Carl Hahn, his son Dmitri took over his father’s firm. The title of Purveyor to the Court was renewed in 1903 in Dmitri Hahn’s name, who also became a Merchant of the First Guild. From 1909 to 1911, Blank worked in partnership with Dmitri Hahn, until that firm closed in 1911 after the death of Dmitri. Blank then established his own independent business, continuing as supplier to the Imperial Cabinet. In 1915, he was appointed Appraiser of the Cabinet, and two years later he was made a Hereditary Honorary Citizen.

Alexander Adolf Treiden (

|

), birth and death dates unknown, of Baltic German stock. It is not known where Treiden apprenticed, nor where or with whom he qualified as a master goldsmith and jeweler. From the early 1880’s until 1894, or possibly 1896, Treiden worked exclusively for the Court Jeweler Hahn. Treiden’s primary responsibility was to produce stock objects for Hahn’s prestigious retail shop. His workshop was situated at 5, Kaznacheyskaya (Street), a 15-minute walk from Hahn’s shop at 26, Nevski Prospekt.

Of some interest are the positions and honorary appointments Treiden held during his career, because they mark his “status” in the St. Petersburg goldsmiths’ community. In 1892, he was registered as a Merchant of the Second Guild, giving him right to own both a workshop and a retail store. In 1908, working as an independent jeweler and shop owner, he was appointed Deputy of the St. Petersburg Assaying Inspectorate, the institution overseeing workshops and retail shops. In 1912, Treiden was elected Treasurer of the Society of Jewelers, Goldsmiths, Silversmiths, and Merchants. The Society was the successor of the old Goldsmiths Guild. Being a trustee of the Society indicates Treiden was a respected member of the St. Petersburg goldsmiths’ world.

Court Jeweler Carl Hahn, Treiden’s employer, had the ambition to offer his clientele a range pour tous les goûts. A fair number of objects produced by Treiden during his time as Hahn’s workmaster have survived which makes it possible to form an opinion about his skills as a craftsman as well as his striking variety in style and technique. He and his team of journeymen were wizards of the goldsmith’s art. The objects to be discussed have been grouped under six headings: Russian Style – Iron Age Nordic Inspiration – Fantasy Objects – Classic Style – Imperial Commissions – Cigarette Cases – Insignia of Orders and Decorations.

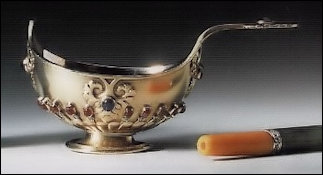

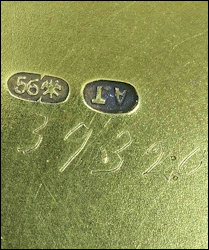

To correct misidentifications both style and marks need to be studied in tandem to arrive at the proper master mark identification. An example where this approach appears to have failed is a gold kovsh (see object #3), a Russian style object by Treiden. Three different master marks (Treiden, Tillander, and Thielemann) have been suggested for the kovsh. A hands-on review of the object with the guidelines suggested in this essay may identify the correct master mark. The workmaster details within [brackets] in the captions are based on the analyses of Treiden’s master mark, styles, and techniques. Treiden left the Court Jeweler Carl Hahn in 1894 or 1896 to establish himself as an independent entrepreneur. In the Treiden examples, the year 1899* is noted with an asterisk, because the hallmark (dvoinik = zolotnik for the gold or silver value of the object, and city mark) punched by the St. Petersburg Assay Office was in use from 1875-1899, and Treiden objects from the Hahn shop are more accurately cited before 1894 or 1896.

Treiden

Treiden  mark on plique-à-jour beaker with dot between the

mark on plique-à-jour beaker with dot between the

letters, ca. 1880. Mark is on the underside of the handle (see #3, #13)

Treiden

Treiden  mark on Imperial presentation box without dot between the letters,

mark on Imperial presentation box without dot between the letters,

ca. 1896. (see #17) (Courtesy Bukowskis, Stockholm)

2. Alexander Treiden Master Mark AT Variations (Courtesy Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm)

3. Plique-à-jour enamel gold kovsh. [Carl Hahn, workshop of Alexander Treiden], ca. 1880. Length 12 cm. Hemispherical bowl supported by three winged griffons, enameled in red scrolls below a similarly designed green band enriched with cabochon rubies, a sapphire, and diamonds. (Attributed incorrectly to Alexander Tillander, St. Petersburg, who “created objects in the style of Faberge for the jeweler Hahn.” Christie’s, Geneva, November 11, 1987, Lot 140; the kovsh now in the Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia, is described as a “decorative stoup, workmaster A. Thielemann”, Object 04/15 in Faberge Museum in St. Petersburg, Exhibit Index, 2014, p. 54; Photograph Riana Benko)

Russian Style

Treiden’s objects in traditional Russian forms and shapes were made in gold or silver-gilt, and frequently enameled in the

plique-à-jour enameling in which translucent or opalescent enamels are fused to span across a network of cells formed with various metals without a backing under the glazed areas. The results are best seen when lit strongly from the back. Treiden made decorative cups, kovshi, charki, and vases, popular in the interior decoration of the well-to-do Russian bourgeoisie of the time. His palette was predominantly clear blue and red color ranges.

CLICK THE ABOVE PICTURES FOR LARGER VIEWS

4. Eagle vase. [Carl Hahn, workshop of Alexander

Treiden]. Marked

AT, St. Petersburg, 1899*. Height 4 1/8 in. (10.5 cm). Silver-gilt,

plique-à-jour enamel, gold, diamonds, rubies. (Attributed to Alfred

Thielemann in the Forbes Magazine Collection

in Forbes, Christopher, and Robyn Tromeur-Brenner.

Fabergé: The Forbes Collection, 1999, pp. 234-235, 290; vase now in the Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg, no further details available.)

5. Gold and plique-à-jour enamel kovsh. [Carl Hahn, workshop of Alexander Treiden]. Marked AT, St. Petersburg, ca. 1895, Length 4 1/4 in. (10.8 cm) of traditional form, the body with foliate scrolls in green and red, with bezel-set rubies, emeralds, spinel and dark pink sapphire (Sotheby’s London, October 29, 2019, Lot 47; attributed to Tillander in Wechsler’s Auction House, Rockville (MD), October 23, 2010)

6. Jeweled charka in 17

th century style with ring foot. [Carl Hahn, workshop of Alexander

Treiden]. Marked

AT, St. Petersburg, ca. 1885. Length 3.5 in. (9 cm). Gold, the three ‘straps’ set with rubies and turquoises, the flat-shaped handle also set with rubies and with a central faceted sapphire. Cyrillic inscription, “Drink to Your Health from this Cup”. (Attributed to Alexander

Tillander, Sotheby’s, New York, June 14, 1989, Lot 349)

7. Jeweled gold kovsh. [Carl Hahn, workshop of Alexander Treiden]. Marked AT and  , St. Petersburg, ca. 1890. Length 4 1/2 in. (10.8 cm). Of traditional form, on spreading circular foot, the partially lobed body with four foliate sprays embellished with four cabochon sapphires, 18 rubies and rose cut diamonds, the flat–foliate handle mounted with a cabochon sapphire. (Christie’s New York, October 20, 1997, Lot 66)

, St. Petersburg, ca. 1890. Length 4 1/2 in. (10.8 cm). Of traditional form, on spreading circular foot, the partially lobed body with four foliate sprays embellished with four cabochon sapphires, 18 rubies and rose cut diamonds, the flat–foliate handle mounted with a cabochon sapphire. (Christie’s New York, October 20, 1997, Lot 66)

Iron Age Nordic Inspiration

The objects in this category are designed in shapes indigenous to the northern parts of Fennoscandia comprised of Norway, Sweden, Finland, as well as Karelia and the Kola Peninsula, both parts of Russia. Treiden uses ornaments inspired (perhaps far-fetched) by Scandinavian objects from the Iron Age. Since the 1860’s, the neo-archeological style had been a fashion in the goldsmith trade all over Europe, and to a great extent in Scandinavia. Each country sought its inspiration from its own ancient art. The neo-archeological style became popular in St. Petersburg toward the end of the 19th century.

8. Charka. [Carl Hahn, workshop of Alexander

Treiden]. Marked

AT, St. Petersburg, before 1899*. Height 1.38 in. (3.5 cm), diameter 1.57 in. (4 cm). Gold, ball feet in lapis lazuli. A wavy border decorated alternatively with small rubies and rose diamonds. Handle shaped as a serpent, echoing creatures in the Nordic mythology. Head of the serpent set with a ruby. (Attributed to A.

Tillander, ‘Fabergé’s main competitor’, Magnin Wedry Auctioneers, Paris, December 12, 2015,

Lot 358)

9. Vodka cup (charka). [Carl Hahn, workshop of Alexander Treiden]. Marked AT, St. Petersburg, before 1899*. Height 2.76 in. (7 cm). Gold, scarlet enamel on swirling and waved guilloché ground, applied sleeve of gold arches inset with rose diamonds, with four emeralds inset under the lip and another on the scroll-shaped handle with dragon-head terminal. (Attributed to A.Tillander, Christie’s, Geneva, April 26, 1978, Lot 265)

The red guilloché enameled gold charka (see #10) is a joy to the eye. Its enameling is of the highest quality and shows the workshops of Carl Hahn had skillful men at the guilloché machines as well as very talented enamellers. The charka’s gold handle is formed of an imaginary mythological creature, either a reptile or a dragon. The head of the creature is set with a long narrow rectangular ‘baguette-cut’ emerald. The border and the body of the charka are applied with gold Nordic Iron Age types of twists and plaits.

10. Charka. [Carl Hahn, workshop of Alexander Treiden]. Marked AT, St. Petersburg, before 1899*. Height 1.77 in. (4.5 cm), diameter 2.52 in. (6.4 cm). Gold-mounted, guilloché enamel with a ‘baguette-cut’ emerald. (Previously attributed to A.Tillander. Courtesy Private Collection. Photograph Robert Hickerson)

Fantasy Objects

Court Jeweler Carl Hahn also introduced cups and bowls decorated with motifs from the ancient Greek and Roman world with handles formed of winged female busts, sometimes without wings but with raised arms. The décor includes chased palmette borders and ribbon-bound laurel or acanthus garlands hanging on the body of the object.

Sweetmeat dish (Length 5.71 in., (14.5 cm) and a cup (Length 3 1/8 in., 8 cm) both by Carl Hahn,

workshop of Alexander Treiden. Marked AT, St. Petersburg.

11. Oval two-color gold and enamel sweetmeat dish,

11. Oval two-color gold and enamel sweetmeat dish,

before 1896. Of royal blue guilloché enamel with

stiff-leaf and pellet border andlaurel garlands suspended

from rosettes, the sides with two winged female busts.

(Attributed to Alexander Tillander with a lengthy

commentary on his style, Christie’s, Geneva,

May 14-15, 1985, Lot 385)

12. Cup, 1885. Gold, enameled translucent royal blue over a

12. Cup, 1885. Gold, enameled translucent royal blue over a

guilloché ground and applied with ribbon-tied swags of

acanthus leaves, with one winged female figural handle,

in fitted holly wood case.

(Attributed to Alfred Thielemann in Sotheby’s, New York,

June 28, 1979, Lot 409, and to Alexander Tillander,

Sotheby’s, December 8, 1992, Lot 474)

13. Gold tankard. [Carl Hahn, workshop of Alexander

Treiden]. Marked

AT with a dot. St. Petersburg, ca. 1895. Height 2 3/8 in. (6 cm) Reeded egg-form body, the hinged lit inset with a gold ruble of Catherine II dated 1779, the scroll handle enclosing a rosette and set with cabochon sapphires and garnets, stock number

39320, French import marks. (Illustrations courtesy Sotheby’s London, June 10, 2009,

Lot 563; same descriptive text with a caveat also in Christie’s London, November 30, 2015,

Lot 241)

The miniature tankard, difficult to place into a style category, auctioned by both Sotheby’s and Christie’s, was cautiously cataloged by both auction houses “probably by Treiden” and “possibly by Hahn”. Based on design, decorative elements and the master’s mark, there should be no doubt about the maker of the object.

Classic Style

The Treiden workshop produced objects in designs which can be called Classic, Timeless, Modernist, or Contemporary. Two table frames are examples of the classic style genre, sparsely decorated, uncomplicated in form, rectangular, with rounded tops, and standing on three stud feet. Their décor is limited to the majestic scarlet red translucent enamel on a wavy guilloché ground. The larger (see #14) of the two frames has plain rose gold borders, whereas, the miniature frame (see #15) has a border of gold beads and a stylized laurel leaf border encircling its aperture.

Table frame (Height 5 7/8 in., 15 cm) and a miniature frame (Height 2.99 in., 7.6 cm) both by Carl Hahn,

workshop of Alexander Treiden. Marked AT, St. Petersburg.

14. Treiden table frame with original

14. Treiden table frame with original

photograph of Empress Maria Feodorovna

(Christie’s, London, November 27,

2017, Lot 203)

15. Treiden miniature frame, attributed

15. Treiden miniature frame, attributed

to Alexander Tillander

(Christie’s, Geneva,

April 26, 1978, Lot 266)

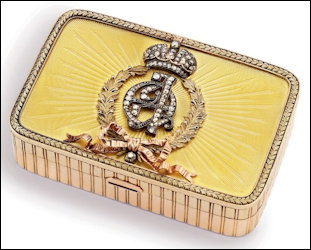

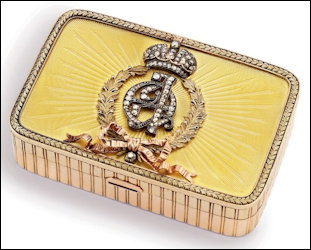

Imperial Commissions

Alexander Treiden’s primary responsibility was the production of objects for Hahn’s regular retail stock. In addition, he made a part of the Imperial commissions received by his employer, in particular, gold presentation boxes set with the sovereign’s cipher. Recent research in St. Petersburg by Dr. Tatiana N. Cheboksarova on Imperial presentation boxes with the cipher of Emperor Nicholas II and that of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna confirms Hahn was second only to Fabergé as a primary maker of these boxes. Between 1895 and 1911, the Cabinet of His Imperial Majesty commissioned 267 presentation boxes with the Emperor’s cipher. Of those, some 70 boxes were made in Hahn’s two workshops. It has not been possible to determine exactly how many boxes were made by Treiden or Carl Blank. The majority appear to be from Blank’s workshop.

16. Imperial Presentation Case. [Carl Hahn, workshop Alexander

16. Imperial Presentation Case. [Carl Hahn, workshop Alexander

Treiden]. Marked AT, St. Petersburg, ca. 1890. Length 3 7/8 in.

(9.8 cm). Two-color gold-mounted guilloché enamel with a

diamond-set cipher of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna.

(Attributed to A.Tillander, Christie’s New York, March 18, 2005,

Lot 74; Christie’s, London, June 8, 2010, Lot 160)

17. Imperial Presentation Case. [Carl Hahn, workshop of Alexander Treiden]. Marked AT, St. Petersburg,

before 1899. Width 3.15 in. (8 cm). Gold, guilloché enamel, diamond-set cipher of Emperor Nicholas II.

(Courtesy Bukowskis, Stockholm)

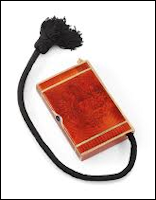

18. Imperial presentation cigarette case. [Carl Hahn, workshop of Alexander

Treiden]. Marked

AT, St. Petersburg, 1893. Width 3 5/8 in. (9.2 cm). Two-color gold,

guilloché enamel, thumbpiece set with a cabochon sapphire. With facsimile handwriting of Emperor Alexander III in Russian ‘From Papa / 25 Dec. 1893 / Gatchina’ (Christie’s London, November 27, 2017,

Lot 216, hard copy auction catalog includes lengthy research for the commissioned object)

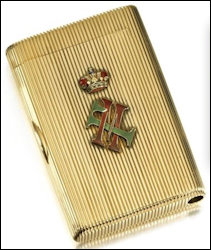

Cigarette Cases

Gold cigarette cases were best-sellers for jewelers at the time. Carl Hahn had a limited production for the Cabinet of His Imperial Majesty Nicholas II and for private customers. Most of them appear to have been made in the workshop of Alexander Treiden.

19. Cigarette case. [Carl Hahn, workshop of Alexander

Treiden]. Marked

AT and

, St. Petersburg, ca. 1892. Width 3 5/8 in. (9.3 cm). Gold and enamel. Cipher of Grand Duke George Mikhailovich, surmounted by a crown with an enameled inscription in Cyrillic on the reverse (above) and on the inside. (Sotheby’s London, June 10, 2009,

Lot 562)

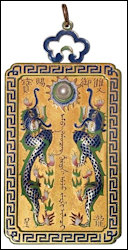

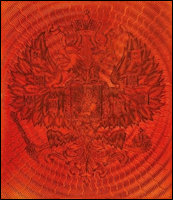

Insignia of Orders and Decorations

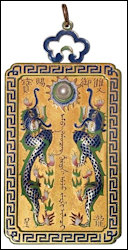

Carl Hahn’s commissions for insignia of foreign orders and decorations is not a surprise, since he was one of the most important makers of the diamond-set badges and stars of the Russian Empire’s most prestigious decorations. Examples of badges and stars of the Empire of China and the Emirate of Bukhara have been preserved from the workshop of Alexander Treiden.

20. Insignia of the

20. Insignia of the

Imperial Order of the

Double Dragon, China.

Qing Dynasty,

(Model 1882-1902),

I Type, I Class, III Grade.

[Carl Hahn, workshop

of Alexander Treiden].

Marked AT, St.

Petersburg, before

1899*. 3.54 x 2.46 in.

(8.98 x 6.25 cm). Gold,

enamel and coral.

(Courtesy A La Vieille

Russie, New York)

21. Star of the Order of the Noble Bukhara, Emirate of Bukhara. Instituted in 1881, the Order had eight (8) classes. The star represents a class

between the 3rd – 6th class. The knighthoods of Bukhara have so far been poorly researched. Carl Hahn, workshop of Alexander Treiden.

Marked AT, St. Petersburg, before 1899*. Gold and enamel.

(Information and illustrations courtesy of Serguey S. Levin, Senior Research Fellow at the Department of Numismatics,

State Historical Museum, Moscow)

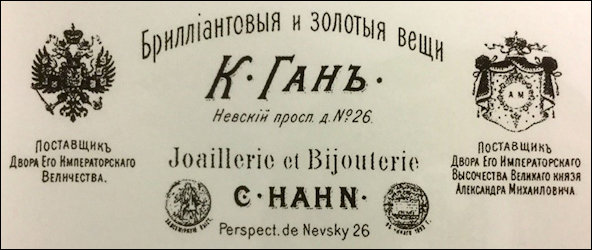

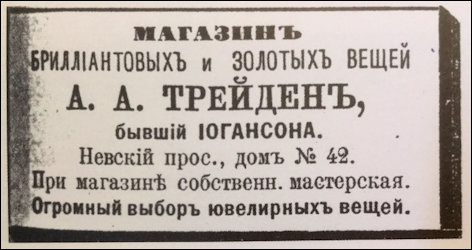

Alexander Adolf Treiden (now an Independent Jeweler) after the death of the master goldsmith Nikolai Solomonovich Johanson (active 1866-94), purchased in 1894 (possibly 1896) the Johanson retail store and workshop located a few blocks away from Hahn’s shop at 42, Nevski Prospekt. A 23-year-long period as an independent jeweler began for Treiden. The business he bought was well-established, because toward the end of his long jewelry career Johanson had succeeded in becoming a supplier to the Imperial Court. On his business card, Johanson stated his firm had an ‘extensive stock of jewelry products’ (Огромный выбор ювелирных вешей). Treiden adopted the same marketing slogan on his own business card. He did not, however, succeed in taking over Johanson’s commissions for the Cabinet of His Imperial Majesty.

22. Alexander Adolf Treiden’s Business Card as an Independent Jeweler from 1894/1896-1917.

22. Alexander Adolf Treiden’s Business Card as an Independent Jeweler from 1894/1896-1917.

(Courtesy of Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm)

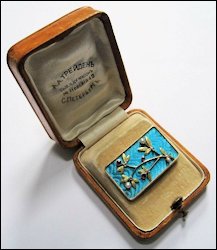

Only a few pieces of jewelry can be documented from the years when Treiden worked independently – a gold brooch (see #23) in the Mughal style, an Indian handicraft and architectural tradition, believed to have been made by Alexander Treiden shortly after he became an independent entrepreneur/jeweler in 1894/1896, and an attractive brooch (see #24) in the Japanese style which retains its original fitted box with Treiden’s name printed on the silk lining of the cover’s inside. More than 14 years after having purchased Johanson’s company, Treiden still refers to the previous owner Johanson on the silk lining.

23. Brooch. Alexander Treiden. Marked

AT, St. Petersburg, before 1899. Diameter 1 in. (2.54 cm). Gold, enamel, diamonds and an emerald. (Freeman’s, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, October 17, 2017,

Lot 16)

24. Brooch. Alexander Treiden. Marked AT, St. Petersburg, 1908-1917. Width 1.46 in. (3.7 cm). Gold, turquoise guilloché enamel and precious stones. Original fitted case marked with the former N. Johanson location. (Courtesy Fabian Stein & Co.)

Alfred Thielemann (active 1890’s-1910,

) was a second-generation master goldsmith and jeweler at the Faberge firm. His father Karl Rudolph Augustovich Thielemann, of German stock, was the owner of a workshop specializing in small jewelry, badges, and jettons. At the age 12 in 1882, Alfred started as an apprentice in his father’s workshop, located at Fabergé’s former address, 11 Bolshaya Morskaya, and later also the address of Fabergé’s workmaster Mikhail Perkhin. Two years later Perkhin had qualified as a master goldsmith, and shortly thereafter, he opened his own studio next door to Thielemann. They both worked for Fabergé during this time.

The younger Thielemann earned his master’s certificate around the year 1890. Both he and his brother Otto (?-1896), also a goldsmith, remained steadfast to their family business. After Karl Rudolph’s death (ca. 1895), Alfred assumed responsibility for the workshop. In 1901, both he and Mikhail Perkhin were offered premises in the workshop wing of Fabergé’s new headquarters at 24 Bolshaya Morskaya – an opportunity both of them eagerly accepted. In the process, Thielemann became the second jeweler of the firm. The Thielemann workshop produced a mass of small jewelry items in gold and silver set with precious stones, and often with guilloché enamel, as well as Fabergé’s smaller commissions from the Cabinet of His Imperial Majesty, such as brooches, tie pins, cufflinks, and rings with the Imperial emblems – the Imperial crown or the double-headed eagle. In addition, the workshop made badges and jettons of very high quality, especially those ordered by the Nobel companies. Miniature Easter egg pendants were crafted by the hundreds in time for the Easter holidays. In 1893, Alfred had married Elisabeth Emilie Olga (Aleksandrovna) Körtling. After her husband’s death on April 26, 1910, Elisabeth inherited his workshop. She acquired a widow’s mark, her initials ET in an oval cartouche (  ), and continued her work with the help of her late husband’s assistant, master goldsmith Vladimir Gavrilovich Nikolaev.

), and continued her work with the help of her late husband’s assistant, master goldsmith Vladimir Gavrilovich Nikolaev.

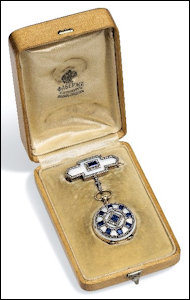

25. Pendant watch. Fabergé, workmaster Alfred Thielemann. Marked

AT, St. Petersburg, 1908-1917, stock number

17915. Height 2 3/8 in. (5.9 cm). Gold, guilloché enamel, set with nine square-cut sapphires within rose-cut diamonds. The watch is suspended from a similarly decorated bar-brooch with a white enamel dial displaying a black Arabic chapter ring and gold hands. It is signed ‘H[enry] Moser & Cie’. Original silk and velvet-lined wood case stamped

Fabergé St. Petersburg, Moscow, London beneath the Imperial warrant. (Christie’s, London, November 28, 2016,

Lot 218)

26. Imperial Presentation Brooch. Fabergé, workmaster Alfred Thielemann, St. Petersburg, 1908-1917. Stock number 2723. Circular, formed as a laurel-chased wreath, with a cabochon set sapphire, centering a diamond-set Imperial crown with two cabochon sapphires, the reverse rose gold. Auction catalog illustrates an invoice which leads to this provenance:

Supplied by Fabergé to the Imperial Cabinet on 15 September 1910 at the cost of 150 rubles, under the number 753. Presented to the wife of Lieutenant Vilde in December 1910 (Christie’s London, July 1-21, 2020,

Lot 62)

A.Tillander (active 1860-1917,

|

|

|

) The family business was owned by Alexander Edvard Tillander (b. 1837-1918) and his son, Alexander Theodor Tillander (b. 1870-1943). They were manufacturing jewelers. Alexander Edvard Tillander was the son of a tenant farmer in Helsinki, Finland. In 1849 at age of 12, he left home for St. Petersburg in order to learn a trade. Eleven years later in 1860, he qualified as a master and established himself as an independent goldsmith/jeweler. Alexander Theodor (known as A. Tillander, Jr.) began training in his father’s workshop under the direction of the Finnish master goldsmith Johan Lönnström. After a three-year apprenticeship at home and an equally long period of practice with well-known firms in Europe, he entered his father’s firm and shouldered his share of responsibility in running both its workshop and the retail shop.

The central products of the firm were jewelry of all kinds, ranging from small gold jewelry to fine jewelry set with diamonds and other precious stones and pearls. Tillander also manufactured medals for awards and commemorative medals as well as gold and enameled jettons for a large number of private railway companies, private enterprises, societies, and organizations. An assortment of small objects of art and vertu included miniature frames, cane handles, and bell-pushes in gold or silver-gilt, often enameled and decorated with precious stones. Between 1896 and 1914, the firm supplied the Cabinet of His Imperial Majesty with gold and silver cigarette cases and numerous small jewels highlighted with Imperial emblems, such as brooches, cufflinks, pendants, and tie-pins. Several members of the Imperial family, especially, Grand Duke and Grand Duchess Vladimir Aleksandrovich and their children, were regular customers of A.Tillander.

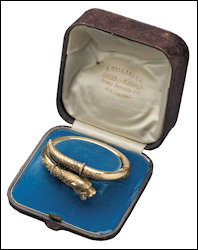

27. – 28. Bracelets in neo-archeological style object – (left) gold with a serpent motiv, and (right) gold, shaped in the form of a mythical animal. A.Tillander, 1880s. (Tillander-Godenhielm, Ulla. Jewels from Imperial St. Petersburg, 2012, p. 261)

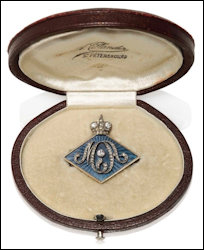

29. Imperial Presentation brooch. A.Tillander, St. Petersburg, ca. 1910. Gold, diamonds and guilloché enamel. Crowned initials of Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna of Russia, daughter of Alexander II, Duchess of Edinburgh, and Duchess of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. (Christie’s London, November 27, 2017,

Lot 210)

30. Pair of gem-set gold and enamel Imperial Presentation cufflinks. A.Tillander, St. Petersburg, 1908-1914. In the form of imperial crowns set with cabochon rubies, the bars enameled in translucent red over engine-turning. (MacDougall’s London, November 27, 2013, Lot 412)

Both objects in a fitted box, the interior of the lid stamped A.Tillander, St. Petersbourg with the French spelling of St. Petersburg.

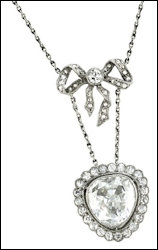

31. Diamond necklace. A.Tillander, Petrograd, 1916 (St. Petersburg was renamed in 1914). Platinum, brilliant-cut and rose-cut diamonds. The necklace was commissioned for his wife by the entrepreneur Robert Runeberg, owner of a successful engineering company in St. Petersburg. #31 and #33 are in original cases.

32. Brooch. A.Tillander, Petrograd, 1914. Gold, platinum, diamonds, emerald.

33. Pendant. A.Tillander, St. Petersburg, ca. 1910. Platinum and diamonds. (Illustration #31-33 from Tillander-Godenhielm, Ulla. Jewels from Imperial St. Petersburg, 2012, pp. 264-265)

In 1911, the A.Tillander firm moved to shop premises at 26, Nevski Prospekt. The business of Court Jeweler Carl Hahn had closed its doors after the death of Dmitri Hahn. The lease of the premises was purchased by Tillander for 12,000 rubles. The better location of the new retail store made it possible for the firm gradually to be considered one of the important jewelers in the Imperial capital. The firm gained further prestige when it took over the entire stock in Russia of the Paris jeweler Boucheron, whose Moscow branch was closed when its managers – father and son – were murdered on a return journey from Baku on the coast of the Caspian Sea. The transaction was the beginning of an inspiring and long-lasting collaboration with Boucheron, and it doubled instantly the Tillander firm’s turnover.

Since there was not room for the workshop on the same premises as the retail store, the workshop was sold to the firm’s head master goldsmith Theodor Weibel, who had worked for Tillander since he began his training there. Between the years 1912-1917, Weibel produced jewels and objects for A.Tillander’s retail shop as well as the firm’s private and Imperial commissions. Theodor Weibel, marked his production with his initials in a lozenge-shaped cartouche (T.W  ).

).

CLICK THE ABOVE PICTURE FOR A LARGER VIEW

CLICK THE ABOVE PICTURE FOR A LARGER VIEW

34. Art Nouveau pendant. Marked AT for A.Tillander, St. Petersburg, 1899-1908. Gold, enamel, diamonds, rubies, pearl. Height 2.36 in. (6 cm). (Courtesy Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm)

The Revolution in March 1917 not only halted the A.Tillander’s expansion, but put an end to the entire period in St. Petersburg. By the time the business closed down officially, on September 1, 1917, Alexander Theodor Tillander (A. Tillander, Jr.), had moved to Finland with his family. His father Alexander Edvard stayed in St. Petersburg, saying that this was where he belonged. The city had been his home for almost seven decades. The old man died in December 1918. In September 1918, the family business was re-opened by Alexander Theodor Tillander in Helsinki, where it continues to this day.

Antti Taivainen (active 1892- after 1930,

|

) was born in Finland at Ruskeala, near Sortavala on Lake Ladoga (the area is now Russian territory).

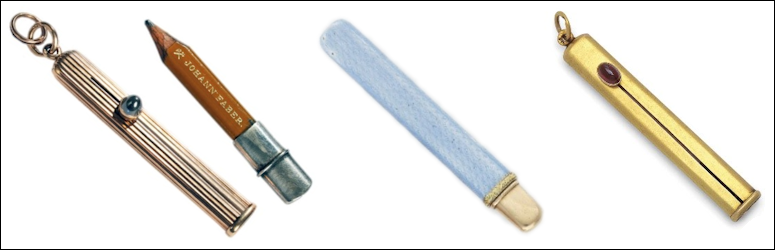

1 He was the son of a tenant farmer, and like many of his countrymen he came to St. Petersburg to find an apprenticeship position for a future trade. He was 14 years old when he arrived, and soon began an apprentice program with the Finnish master goldsmith, E. Matilainen. In 1884, he qualified as a journeyman, and he worked for eight years with various master goldsmiths in St. Petersburg. In 1892, he became a master goldsmith, opened his own workshop in the same year, and worked as an independent master and subcontractor known for a limited production specialty line of readily-saleable articles. Among them were decorative appliances for office desks (holders for pens, pencils, and instruments, fixtures for notepads, toothpick holders, and more). The corps of medical doctors preferred his products. In fact, Taivainen excelled in creating custom-made gadgets for the consulting rooms of a particular group of clients. Nevertheless, Taivainen’s main product were pencils and pencil holders with a simple design. Often reeded in one or several nuances of gold, sometimes set with a small cabochon sapphire or ruby, or with a décor of enamel on a

guilloché ground. His most usual color of enamel was light blue. His workshop was at 6, Bolshaya Koniushennaia, in the very heart of St. Petersburg. In 1919, after sadly having to close his flourishing business, he re-opened with a workshop and retail shop in Viipuri, Finland. His son, Armas Taivainen (1897-1983), who had apprenticed under his father between 1913 and 1917, first assisted and then later took over the family business, which he moved from Viipuri to Helsinki in 1939. The business closed in 1983.

36-38. Pencil Holders by Antti Taivainen

35. Gold Pencil Holder: Antti Taivainen. Marked

A.T., St. Petersburg, 1899-1908. Two-color gold, cabochon sapphire. (Courtesy Taivainen Family)

36. Blue Pencil Holder: Attributed incorrectly to a fictional workmaster with the name of A. Astreiden, St. Petersburg, 1908-1917. Gold-mounted with guilloché pattern under blue enameling. (Christie’s London, November 26, 2018, Lot 206)

37. Gold Pencil Holder: Attributed incorrectly to Alexander Tillander, St. Petersburg, 1899-1904. Garnet cabochon slide-piece, inscribed in Russian ‘From comrades / 24 XI 1903 / EB’. Saleroom Notice suggests “the pencil holder is by Antti Taivainen rather than Alexander Tillander as stated in the catalogue”. (Ibid., Lot 234)

Looking Back at the AT Goldsmith Master Mark Confusion

The mix-up of the masters discussed in this paper was originally the result of Alexander Treiden’s name and identity having “slipped through the net” of scholars researching the goldsmiths of St. Petersburg during Imperial times. Two pioneer researchers/authors were Henry Charles Bainbridge, manager of the London Faberge branch from 1906-1917, who reminisces in his 1949 book

2 about his time with the firm, and A. Kenneth Snowman, British Faberge dealer since the 1920’s, and the curator of the Special Coronation Exhibition in his 1953/1962 monograph

3. Neither of them mentions Alexander Treiden. In the second wave of pioneering research, Treiden’s name appears only in passing, if at all, without any details.

4 The identity of Alexander Treiden was instead given to the Finnish jeweler Alexander Tillander, and to further confuse the mark identification process a fictitious master by the name of A. Astreiden

5 appeared in the 1980-1990’s.

Bainbridge, who did the initial and much-admired spadework on Fabergé’s history and work, must have touched in his discussions with Carl Fabergé’s two sons, Eugène (b. 1847-1960) and Agathon (b. 1876-1951), on the subject of the Court Jeweler Carl Hahn, the closest competitor to the Faberge firm.6 Indeed, Bainbridge says:

“But one thing Thielemann had no hand in, in a general way, and that was the making of objects of fantasy. It is well to note this and for this reason. Hahn, a contemporary jeweler and goldsmith in St. Petersburg, employed a workman called A. Tillander, and he made objects of fantasy and marked them A.T. If an object of fantasy should turn up to-day marked A.T., and it falls to someone to assess it who is unacquainted with the workmanship of Fabergé; unless the mark is supported by the mark of Fabergé it should not be accepted as a Fabergé object”.7

This specific paragraph by Bainbridge was taken as fact by the authors above for decades to come. What Bainbridge said was correct in principle; Thielemann did not produce objects of fantasy. Hahn, however did, but his workmaster was not Alexander Tillander, he was Alexander Treiden! In the wake of Bainbridge’s book the A.Tillander name was repeated in every new publication, alternating in two versions, ‘the unknown Hahn workmaster AT’, or as ‘A. Tillander, workmaster of Fabergé’.

During the late 1970s-1990s, a master goldsmith with the name A. Astreiden is cited in auction catalogs, even though no such master existed in St. Petersburg. For example, in an 2018 auction catalog a pencil holder (see #37) made by Antti Taivainen is credited to the ghost master Astreiden. My hypothesis is the fictitious name was the result of an erroneous transliteration of the Cyrillic А.Трейден to this Latin script. In 1997, the Russian author Valentin Skurlov writes:

“In Western literature the mark AA is attributed to a certain fictitious master by name of A. Astreiden, with the address 42, Nevski Prospekt. This address housed the workshop and store of A. Treiden, and even earlier belonged to the Jeweler K. [sic] Johanson. During the second half of the 19th century and in the early 20th century, there was no master by the name of Astreiden in St. Petersburg”.8

Later Skurlov

9 mentions Alexander Treiden in passing and adds the master goldsmith Alexander Treiden collaborated with Fabergé. As his source, Skurlov mentions Eugène Fabergé (died in 1960). Valentin Skurlov himself did not have a direct contact with the long-since deceased son of Carl Fabergé. His source may therefore have been Tatiana Fabergé, the great-granddaughter of Carl Fabergé. Subsequent research has not found evidence of any business connections between Fabergé and Treiden.

In 1980, when the A.Tillander firm celebrated 120 years of existence with an exhibition in Helsinki, a catalog was published containing the history of the firm written by Herbert Tillander, the third generation of the family business. Published in a large print-run, the exhibition catalog10 in three languages – Finnish, Swedish and English – was widely distributed abroad. To this author’s surprise, the misconceptions and erroneous information about the Court Jeweler Hahn and A.Tillander were not corrected in books published during the latter part of that decade and into the 1990s.11 In 2011, Géza von Habsburg in a chapter entitled “Fabergé and His Russian Competitors” for an exhibition catalog12 discusses for the first time in some detail the workmasters of the Jeweler Carl Hahn. The text nevertheless only mentions Alexander Treiden briefly as the other Hahn workmaster, Carl Blank is given more attention. Several other misconceptions are understandable, since the research on these masters was still “on virgin soil”. By 2012, Tatiana Fabergé, Eric-Alain Kohler, and Valentin Skurlov in their encyclopedic publication13 corrected earlier misconceptions on the Court Jeweler Carl Hahn and his workmaster Alexander Treiden, as well as those on the A.Tillander firm during its years in St. Petersburg.

It is hoped the effort involved in gathering biographical details and illustrations of objects complete with the descriptions in order to examine marks, individual styles, and techniques in this paper will further acknowledge four unique St. Petersburg goldsmiths. Their creative work deserves recognition for the special talents each of them contributed to the world of jewelry some hundred years ago.

I wish to thank my friend Christel McCanless, editor and publisher of the Fabergé Research Newsletter, for her meticulous edits, corrections, and comments on the AT paper. She has professionally “shuffled” around my material and made my article readable, and hopefully both useful and enjoyable for all of us interested in the art and work of the St. Petersburg jewelers. Fabergé enthusiast, Riana Benko has been invaluable in finding illustrations to accompany the text, and webmaster Ben Swindle used his computer skills to make the text and illustrations attractive for newsletter readers.

ENDNOTES:

1 The information on Antti Taivainen is based on a 1979 interview with his son, Armas Taivainen.

2 Bainbridge, Henry Charles. Peter Carl Fabergé: Goldsmith and Jeweller to the Russian Imperial Court and the Principal Crowned Heads of Europe, 1949.

3 Snowman, A. Kenneth. The Art of Carl Fabergé, 1953. A revised and enlarged edition with new information was published in 1962. All subsequent editions and impressions are reprints of this edition; Wartski, London. Special Coronation Exhibition of the Work of Carl Fabergé, 1953.

4 von Habsburg, Géza, and Alexander von Solodkoff. Fabergé, Court Jeweler to the Tsars, 1979, p. 154 – A. Treiden is mentioned as one of three masters in St. Petersburg using the master’s mark AT; von Habsburg, Géza. Fabergé, Juwelier der Zaren (English title: Fabergé), 1986, p. 331 – A. Treiden is mentioned as “possibly another independent jeweler”; Lowes, Will, and Christel Ludewig McCanless. Fabergé Eggs: A Retrospective Encyclopedia, 2001, p. 240, states “Treiden was the owner of a St. Petersburg workshop that traded with Fabergé”.

5 von Habsburg, Géza. Fabergé, Juwelier der Zaren (English title: Fabergé), 1986, p. 293, Object 594 is a cigarette case attributed to A. Astreiden (also cited as A. Astreyden); Fabergé, T.F., Gorynia, A.S., Skurlov, V.V. Фаберже и Петербургские Ювелиры (Fabergé and the St. Petersburg Jewelers), 1997, p. 112.

6 The two sons are mentioned by Bainbridge as providers of information on their father’s company.

7 Bainbridge, Henry Charles. Peter Carl Fabergé: Goldsmith and Jeweller to the Russian Imperial Court and the Principal Crowned Heads of Europe, 1949, pp. 129-131 based on the editions consulted for verification.

8 Fabergé, T.F., Gorynia, A.S., Skurlov, V.V. Фаберже и Петербургские Ювелиры (Fabergé and the St. Petersburg Jewelers), 1997, p. 112. (Passage translated from the Russian by Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm.)

9 Ibid., p. 140.

10 Tillander-Godenhielm, Ulla, et al. Carl Fabergé and His Contemporaries, 1980.

11 For example, Hill, Gerard, et al. Fabergé and the Russian Master Goldsmiths, 1989, pp. 12, 28, 43, 48.

12 von Habsburg, Géza. Fabergé Revealed at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, 2011, pp. 42-57.

13 Fabergé, Tatiana F., Kohler, Eric-Alain, and Valentin V. Skurlov. Fabergé: A Comprehensive Reference Book, 2012, pp. 56-57 (Treiden), and p. 121 (Astreiden).

and

and  (early 1880s-1894 or 1896 with and without dot)

(early 1880s-1894 or 1896 with and without dot)

(1894 or 1896-ca. 1917 no dot)

(1894 or 1896-ca. 1917 no dot)

workmaster of Fabergé. His widow, Elisabeth inherited the workshop after his death and continued it until 1917 with the ET

workmaster of Fabergé. His widow, Elisabeth inherited the workshop after his death and continued it until 1917 with the ET  mark.

mark.

(oval 1860-ca. 1880)

(oval 1860-ca. 1880)

(without dot 1880-ca. 1900)

(without dot 1880-ca. 1900)

(with dot ca. 1900-1912)

(with dot ca. 1900-1912)

(whole name ca. 1880-1917)

(whole name ca. 1880-1917)

(dates unknown)

(dates unknown)

(dates unknown)

(dates unknown)

A. Tobinkov, workmaster of Nicholls & Plincke (active 1870-?)

A. Tobinkov, workmaster of Nicholls & Plincke (active 1870-?)

Albanus Toivanen (active 1898-1917)

Albanus Toivanen (active 1898-1917)

![]() , St. Petersburg, ca. 1890. Length 4 1/2 in. (10.8 cm). Of traditional form, on spreading circular foot, the partially lobed body with four foliate sprays embellished with four cabochon sapphires, 18 rubies and rose cut diamonds, the flat–foliate handle mounted with a cabochon sapphire. (Christie’s New York, October 20, 1997, Lot 66)

, St. Petersburg, ca. 1890. Length 4 1/2 in. (10.8 cm). Of traditional form, on spreading circular foot, the partially lobed body with four foliate sprays embellished with four cabochon sapphires, 18 rubies and rose cut diamonds, the flat–foliate handle mounted with a cabochon sapphire. (Christie’s New York, October 20, 1997, Lot 66)

![]() ), and continued her work with the help of her late husband’s assistant, master goldsmith Vladimir Gavrilovich Nikolaev.

), and continued her work with the help of her late husband’s assistant, master goldsmith Vladimir Gavrilovich Nikolaev.

![]() ).

).