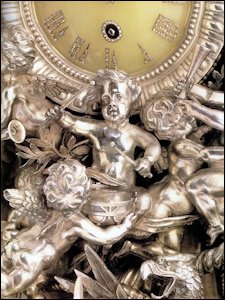

Fabergé workmasters Mikhail Perkhin (1860-1903) born in Karelia, Russia, and Julius Rappoport (1851-1917) from the Kovno province, now part of Lithuania, became master goldsmiths in 1883/84. They were active with the Fabergé firm in St. Petersburg until 1903 and 1908, respectively. Less than ten years after receiving their master papers, a process which can take eight or more years to complete, the Perkhin and Rappoport workshops created monumental wedding anniversary presents for the Russian rulers in 1891, and the Danish monarchs in 1892.

Nicholson Art Advisory, New York City

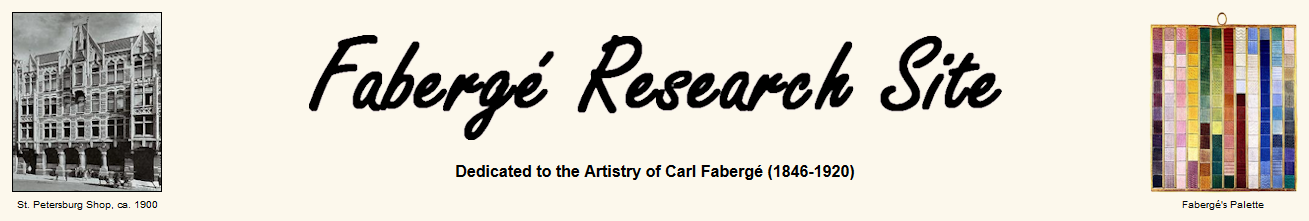

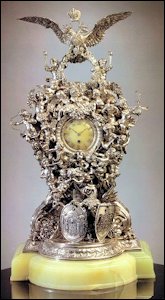

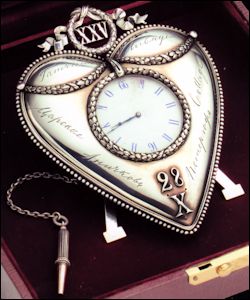

Alexander III 25th Anniversary Clock with Detail,

St. Petersburg, 1891, 27 in. (68.5 cm) high

(Christie’s New York, April 18, 1996, now State Hermitage Collection)

Workmaster Mikhail Perhkin (….П)

(Tillander-Godenhielm, Ulla, Fabergé

ja hänen suomalaiset mestarinsa

(Fabergé and His Finnish

Workmasters), 2008, II 78)

The clock was initially delivered in “oxidized” silver (meaning patinated to a dark matte finish), but we know from archival photographs that by 1902, extensive polishing had returned the clock to a fairly bright silver. The piece was first exhibited at the famous von Dervis exhibition sponsored by Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, and after the exhibition, the piece was returned to the Antichkov Palace, where it remained in the Benois-designed “Blue Salon” until the revolution. The clock was left behind by the Dowager Empress when she escaped Russia through Kiev and the Crimea during the revolution. It was sold by the Soviet authorities later. The clock was rediscovered in an American collection, and was exhibited for the second time in the 1993-1994 exhibitions, Fabergé: Imperial Jeweler at the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, and then at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Extensive research and documentation accompanied the clock, provided by the noted experts Dr. Géza von Habsburg, Dr. Marina Lopato, and the Russian Fabergé independent researcher, Dr. Valentin Skurlov.

When the owner decided to sell the clock in 1996, Christie’s New York was chosen, where I was then a specialist in the Russian Works of Art department. The piece generated extraordinary excitement for many reasons. It was among the very first times access to Russian sources for research was available, and thanks to the work of von Habsburg, Lopato, Skurlov, Christie’s International Russian department head Anthony Phillips, and London department specialist Alexis de Tiesenhausen, a new level of scholarship for a Fabergé object was available to potential buyers. 1994 was the also first time a Fabergé object at auction (The Winter Egg) was published with an original bill but the clock was the first time original internal documentation from both Fabergé and the Imperial Archives were used as resources.

Russian buyers were also beginning to participate in the auction market, and so the catalogue was published both in English and in Russian – a first for an auction house. The Russian ruble appeared on the conversion board at Christie’s for the very first time – but only after an announcement from the podium that the board would be using the “official” rate of conversion, rather than the actual “market” rate. The clock sale realized $1,652,500, setting a triple record; for silver (the Hanover Chandelier from the collection of Hubert de Givenchy having set the previous silver record of just over $1 million at Christie’s Monaco on December 4, 1993, Lot 95), clocks, and Fabergé (other than an Imperial Egg). (First published in Romanov News, No. 81, December 2014, Paul Kulikovsky, publisher, reprinted with permission of the author and editor)

Houston Museum of Natural Science, Texas

She became betrothed to the handsome and dashing Tsesarevich Nicholas Alexandrovich (1843-1865) at the end of 1864, receiving an imposing multiple-strand necklace of large, perfectly matched pearls from his parents Alexander II and his wife Empress Maria Alexandrovna. Unfortunately, tragedy struck before the wedding could take place, he fell ill in Nice and died of meningitis in 1865. Not to be deterred, her mother and future mother-in-law decided she should marry his brother, Grand Duke Alexander Alexandrovich, the new Tsesarevich and later Alexander III. He was a man equally tall, well-built, attractive and very strong. He was a bull of a man! It is said he used to entertain his dinner guests by bending iron rods and silverware with his bare hands.

Emperor Alexander III

(1845-1894)

(Courtesy Wiki)

Maria Feodorovna,

neé Princess Dagmar of Denmark

(1847-1928) wearing engagement pearls.

(Hall, Coryne, Little Mother of Russia,

1999, Back Cover)

One cold early spring day in March of 1881 their happy life was shattered when the Emperor, Alexander II, was assassinated by revolutionary terrorists while returning via the Griboedov Canal to the Winter Palace. The famous Church of the Savior on Spilled Blood was erected on the spot between 1883 and 1907. Russia had a new Emperor, Alexander III, a man who surely had not meant to assume power so soon, since his father had been a healthy man. Despite the change in their circumstances, Maria and Alexander remained close. She was a devoted mother and doting parent, and was also an elegant consort who brought a great deal of style to the court of the most powerful ruler in Europe. She set a high bar for elegance and the court slavishly followed her whims.

Alexander III 25th Wedding Anniversary Desk Clock

(Courtesy A La Vieille Russie and McFerrin Collection)

Like many of the clocks created by Fabergé workshops, this clock has a Moser & Cie 8-day movement and a tiny key on a chain to make it easier to wind the clock. The entire piece is 5 inches high. It was not meant for anyone to see from a distance. It was meant to be very personal. So, to whom did Alexander entrust this special gift’s creation? Fabergé of course! And in turn, Fabergé entrusted the commission to his leading silversmith Julius Alexandrovich Rappoport. (Fabergé, Tatiana F., Kohler, Eric-Alain, and Valentin V. Skurlov, Fabergé: A Comprehensive Reference Book, 2012, 248-250)

Heritage Auction Galleries in Dallas, Texas, featured the clock in an auction — The James C. Russo Collection of Russian and British Royal Objects, April 24, 2008, Lot 36054). In an interview Mr. Russo described the clock as “the epitome of what I love” (to collect). Featured on the cover of the auction catalog, this charming little desk clock, has been passed gently from collector to collector since leaving Russia, and now it rests in the McFerrin’s magnificent collection. How fitting it is that the Imperial clock is enjoyed by a Texas couple who are so fond of one another! Docents at the Houston Museum of Natural Science eagerly await the news when the clock will join the stunning collection of 500+ items already on view from the McFerrin Collection.

My special thanks to the McFerrin Collection, and especially to Mrs. Dorothy McFerrin in particular for information regarding the desk clock, and to John Atzbach for photographs and additional details.

Commissioned from the House of Fabergé the objects were presented to King Christian IX (1818-1906) and Queen Louise (1817-1898) of Denmark, the parents of Empress Maria Feodorovna (1847-1928), for their Golden Wedding Anniversary celebrated on May 26, 1892. The impressive family heirlooms consist of a pair of silver-gilt wine coolers and a colossal silver-gilt kovsh. Both were created in the workshop of workmaster Julius Rappoport, who specialized in large silver items and was an active workmaster from 1883-1908. Fabergé’s invoice for both the wine coolers and the kovsh dated October 15, 1892, states the order totaled 10,000 rubles. To this day the gifts retain their original, fitted oak cases with brass fittings. The silk label inside each case bears the name ‘C. Fabergé’ in Latin letters beneath the Imperial eagle and ‘St. Petersburg’ in Cyrillic. The label within the kovsh’s wooden case can be clearly seen in the video.

Danish Royal 50th Wedding Anniversary Gifts: Wine Cooler, Design Sketch and the Kovsh

(Left and right: von Habsburg, et al., Fabergé, 1987, 130-131, Middle: Christie’s London, April 27, 1989, Lot 404)

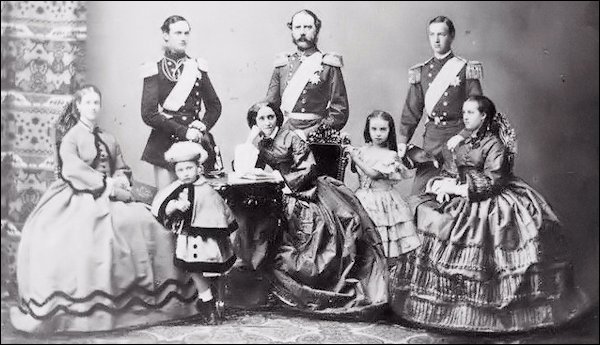

1862: Future King Christian IX of Denmark, His Wife Louise of Hesse-Kassel and Their Six Children at the Time of Princess

Alexandra’s Engagement to the Prince of Wales.

Left to right: Dagmar, Frederick, Waldemar, Louise (Later Queen), Christian (Later King), Thyra, William, and Alexandra.

(Aronson, Theo, A Family of Kings, The Descendants of Christian IX of Denmark, 1976, facing p. 116)

The massive Imperial presentation kovsh was a personal gift from Emperor Alexander III of Russia and his wife Empress Maria Feodorovna (neé Princess Dagmar of Denmark). It measures 88.2 cm in length, 74.1 cm in height, and 61.8 cm in depth (35 x 29 x 24 inches, Fabergé Research Newsletter, Winter 2013-14). In the video Krog explains the silver-gilt kovsh has the capacity to hold approximately eight bottles of champagne on ice and is still used by the Danish Royal family today. Of traditional form with a scrolled handle it is surmounted by an elephant with a turret on its back, the elephant being a symbol of chastity and the defense of the Christian faith. Two extant, original Fabergé design sketches for this golden anniversary kovsh along with a design for an unrelated Imperial presentation kovsh were sold as one lot by Christie’s London on April 27, 1989, for 4,950 GBP. Neither sketch shows the turret atop the elephant’s back, but one can presume the turret was incorporated into the kovsh’s design to emulate the badge of the Order of the Elephant, Denmark’s highest chivalric order.

The kovsh’s silver elephant has gilt tusks, a figure of a Moor mahout riding on its neck, a red and white enameled turret set with clear quartzes on its back, and a blue-enameled saddle applied with royal monograms on each side. The video also reveals the elephant has clear stones for eyes and a square, clear stone in its forehead. The front of the kovsh bears the coats-of-arms of the Royal Houses of Denmark and Hesse-Kassel within a rococo cartouche, and the sides are decorated with the conjoined, crowned monogram ‘CLIX’ and ’26 Mai 1842-1892′, the dates of the wedding and the golden wedding anniversary, within foliage and scroll cartouches.

The wine coolers and kovsh remain in the collection and care of the Danish Royal Family. They are reminders of a bygone era and the role King Christian IX and Queen Louise played in European politics through the dynastic marriages of their children. These magnificent Fabergé objects symbolize the love and respect shown to the Danish monarchs by their extensive family when they reached the important milestone of half a century of marriage. In a letter of thanks to the nation, King Christian IX wrote:

“We had been looking to forward to celebrating our Golden Wedding with joy and thankfulness in a family festival amongst our children and our children’s children. The day came – and our people’s affectionate sympathy transformed a quiet family rejoicing into a national festival. The testimonies of sympathy and well-wishing which the day has brought us have been innumerable: affectionate congratulations and demonstrations of every kind, gifts large and small – both to us personally and to some charitable purpose – but all alike valued by us for the sentiment which inspires them.” (Madol, Hans Roger, Christian IX: Compiled from Unpublished Documents and Memoirs, 1939, 244-45)

Riana Benko, DeeAnn Hoff, and Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm contributed to the research for this essay.

Major Resources Consulted:

- Christie’s London, Designs from the House of Carl Fabergé, April 27, 1989, Lot 404.

- Krog, Ole V., Maria Feodorovna Empress of Russia: An Exhibition about the Danish Princess Who Became Empress of Russia, 1997, 444-448.

- von Habsburg, Géza and Marina Lopato, Fabergé: Imperial Jeweler, 1993, 232-235.

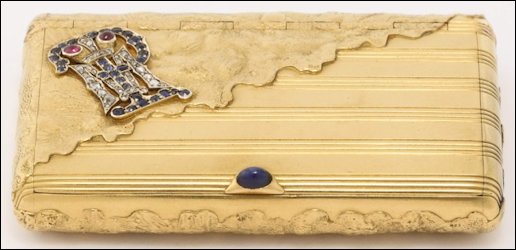

Important European Silver, Vertu, and Russian Works of Art

Cigarette case given by Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna to her maid-of-honor Princess Catherine (Ekaterina) Pavlovna Galitzine (1896-1988), daughter of Prince Paul Golitsyn (1856-1914/16), Nicholas II’s Master of the Imperial Hunt, and Princess Alexandra Meshcherskaya (1864-1941), a maid-of-honor to Empress Alexandra. In 1922, Catherine married Capt. James Haldane Adair Campbell (1893-1945), a son of the Laird of Tullichewan and great-grandson of William F. Havemeyer, the illustrious mayor of New York. The Campbell family crest and motto, ‘True to the End’ was added to the underside.

Cigarette Case with Campbell Family Crest

(Courtesy Sotheby’s)

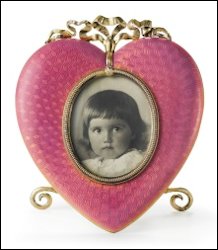

Silver-gilt and Guilloché Enamel Photograph

Frame by Anders (Antti) Nevalainen,

St. Petersburg, 1899-1904

(Courtesy Christie’s)

Important Silver and Objects of Vertu, Russian Works of Art

Sale features objects from American private collections including some from descendants of Grand Duke George Mikhailovich (1863-1919), the grandson of Emperor Nicholas I and first cousin of Emperor Alexander III. Among the highlights of the collection is a photograph frame, purchased directly from Fabergé’s St. Petersburg shop by Emperor Nicholas II in July of 1907.

Bowenite from an Asbestos Mine,

Warren County, New York

(Wiki)

1892 Diamond Trellis Egg

(Courtesy McFerrin Collection, Houston, Texas)

Art conservator Carol Aiken observed:

Archival records, such as invoices, sales logs, or personal letters, would seem to be a reliable source for information on what stones or metal were used in creating a Fabergé object, but they can be misleading. Mistakes creep in when sales log entries are made in haste, or just the color of a stone is recorded, or some materials are left out completely. And in the case of bowenite, Fabergé did not use the term in his invoices, but generally referred to stones from the serpentine family as jadeite, which it very much resembles, so much so that the materials were often used interchangeably. In answer to the question initiating this discussion, the shell of the Diamond Trellis Egg is identified by the Houston Museum of Natural Science as bowenite.

Another common issue in the Fabergé invoices is a liberal use of the term “topaz” to refer to stones in the quartz family. Perhaps it was seen as a more elegant and marketable term, so “smoky quartz” became “smoky topaz”, and “citrine quartz” became “golden topaz”, etc. Of course, product enhancement has been a common practice in the advertising world for centuries, but it can be a source of confusion, too. As long as one understands these anomalies of fact exist, one can approach material identification more objectively.

Carol Aiken’s publications relating to this topic include:

- “Imperial Easter Eggs: A Technical Study” in von Habsburg, Géza, and Marina Lopato, editors, Fabergé: Imperial Jeweler, 1993, 76-83.

- “The Many Golds of Fabergé” in Gilded Metals: History, Technology and Conservation, Terry Drayman-Weisser, editor, 2000, 297-306.

- “Mrs. Pratt’s Imperial Easter Eggs” in von Habsburg, Géza, et al., Fabergé Revealed at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, 2011, 88-101.

Searching for Miniatures by Zehngraf

We are searching for six miniatures (ca. 1.5 in. high x 1 in. wide) by Zehngraf of the ‘Emperor Alexander III in different uniforms’ which fit in the folding frame identified by Anna and Vincent Palmade as the missing surprise of the 1896 Alexander III Portraits Egg.

He was born in Copenhagen, Denmark, in 1857 and studied in Denmark and Germany. He lived in Berlin from 1889. Zehngraf carried out orders for miniature portraits for all the royal families of Europe, including many for the Office of His Imperial Majesty, the Tsar. The miniatures were often used in the manufacture of presentation items. Zehngraf’s work is a feature of the 1896 Tsar Imperial Egg with Revolving Miniatures, the 1898 Tsar Imperial Pelican Egg, and the 1898 Tsar Imperial Lilies of the Valley Egg. He died in Berlin in 1908. (Lowes, Will, and Christel Ludewig McCanless, Fabergé Eggs: A Retrospective Encyclopedia, 2001, 245) Contact the Editors.

(Updates are posted in Exhibitions on the Fabergé Research Site)

Splendor and Surprise: Elegant Containers, Antique to Modern

Seven Fabergé objects from the permanent collection including an 1896 Julius Rappoport Table Clock are shown.

March 20 – October 11, 2015 The Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace, London

Painting Paradise: The Art of the Garden

Nine Fabergé flowers from the Royal Collection are on display as part of the exhibition, and here is a closer look at the flowers. (Courtesy of Royal Russia News)

March 27 – July 26, 2015 Queen’s Gallery, Palace of Holyroodhouse, Edinburgh, Scotland

Venue includes three Fabergé objects shown in detail. (Courtesy of Royal Russia News)

The very popular exhibition Fabergé from the Matilda Geddings Gray Foundation Collection currently at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City is on view through November 27, 2016.

Yusopov Archives Donated to the GARF by Viktor Vekselberg

(Courtesy Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg)

1907 Yusupov Egg by Fabergé

(A La Vieille Russie and

Parmigiani, Mechanical

Wonders: The Sandoz

Collection, 2011, 118-9)

Ed. note: No Fabergé objects were included in the sale. The 1907 Yusupov Egg presented by Prince Felix Yusupov to his wife Zenaide on their 25th Wedding Anniversary. A part of the Fondation Eduoard et Maurice Sandoz in Lausanne, Switzerland, the egg is rarely exhibited.

The St. Petersburg Fabergé Museum is short-listed as a “Museum of the Year” for the Art Newspaper Russia Prize in one of the five nominations categories: Book of the Year, Exhibition of the Year, Museum of the Year, Restoration of the Year, and Personal Contribution. The ceremony will be held in Moscow on April 2, 2015.

Recently I was writing about an obscure facet in the life of Kaiser Wilhelm II (1859-1941) of Germany. My research took me to the Museum Huis Doorn in the Netherlands, the former Kaiser’s home during his exile following the First World War. There, I found in the collection several Fabergé items Emperor Nicholas II gave his cousin Wilhelm II before the horrific war that would cost both rulers their thrones and the tsar his life, as well as many millions of ordinary citizens.

Kaiser Wilhelm II in Russian Uniform and Nicholas in German Uniform

(Wiki)

Kaiser Wilhelm II in the

Uniform of the Honorary Colonel-in-Chief of the Russian

85th Infantry Regiment, Viborg

(Wiki)

A third Fabergé picture frame is rectangular with angled corners, the green translucent enamel applied with rosettes and laurel swags and bound by ribbon-tied surmount. The aperture has a bound reeded border. The frame contains an 1861 albumen cabinet card of a young Princess Augusta Victoria of Schleswig-Holstein, who in 1881 married then Prince Wilhelm of Germany (later the Kaiser). The Museum Huis Doorn notes the frame was made by Fabergé, but misidentifies the material as gilt-bronze. Unfortunately, the photographs of these three frames do not show the back or the hallmarks.

Miniature Replica of Peter the Great’s Puska Cannon

(Original in the Hermitage, St. Petersburg)

Cigar Box in the Shape of a Russian Helmet,

Both by Fabergé

(von Habsburg, Géza, et al.,

Fabergé, 1987,126, 128, 190-1)

How the Fabergé pieces and the other items in the Museum Huis Doorn came to be in this small, but elegant estate on the outskirts of Doorn in the Netherlands is an interesting story. In October 1918, Germany was devolving into chaos. The German Army, decimated by three and a half years of war, was reeling from Allied military successes. When Kaiser Wilhelm II met with his military commanders, they bluntly told the Emperor that his army faced military defeat on the Western Front and the war was lost. The Kaiser’s government collapsed. Civilian riots and mutinies in the army and navy rocked Germany. The generals advised Wilhelm in the deteriorating situation, his safety could not be guaranteed.

Wilhelm II sent a note to Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands requesting political asylum. The queen agreed. Kaiser Wilhelm abdicated his throne on November 9, 1918, left his military headquarters in Spa, Belgium, and entered the neutral Netherlands for a life of exile. Ironically, at the same time, Carl Fabergé was beginning his own journey into exile, leaving a chaotic Russia for the relative safety of Germany. Wilhelm II, after initially accepting the hospitality of a fellow member of the Knights Hospitallers of St. John of Jerusalem, purchased the Kasteel Doorn along with 60 hectares near the town of Utrecht in the Netherlands. The owner of the Doorn estate was Baron van Heemstra-de Beaufort, great-grandfather of the actress Audrey Hepburn.

The Kaiser, joined by his wife and a retinue of 40 people, modernized and remodeled the Huis Doorn, as it was thereafter known. Wilhelm was accompanied by seven railway carriages of personal items when he crossed the border into exile. The German Republic allowed an additional 63 rail cars of personal items to be sent. It was all installed in the two dozen medium-sized rooms and the attic. The Huis Doorn was resplendent with the trappings of Imperial Germany, oversized portraits of Wilhelm, other Hohenzollerns, and scenes of German military victories in the Franco-Prussian War. Crested imperial china and glassware graced the dining table. Hundreds of military uniforms and parade helmets filled the closets. Tables and curio cabinets were thick with photographs of the Kaiser Wilhelm’s extended family, cigarette cases, snuff boxes, objects of vertu, and gifts from his fellow monarchs. The exiled Wilhelm II died in 1941 at the Huis Doorn and his tomb is on the grounds. In 1945, the Dutch government appropriated the house, furnishings, and grounds as enemy property. It was subsequently opened to the public as a museum and remains as it did when Wilhelm was in residence.

There very well may be more Fabergé treasures among the many items in the Museum Huis Doorn. The museum has recently undertaken an ambitious project of photographing every object and photograph in the museum’s collection and putting the images online. If you are planning a trip to the region, the museum is certainly worth a visit – and with advance notice specific items may be inspected.

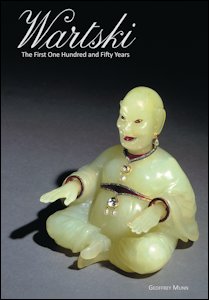

Wartski – The First One Hundred and Fifty

Years by Geoffrey Munn, 2015

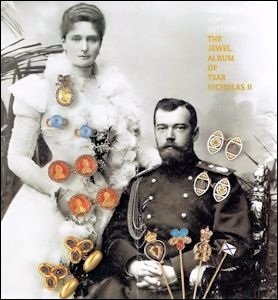

The Jewel Album of Tsar Nicholas II

by Alexander von Solodkoff, 1997

(Courtesy Royal Russia News)

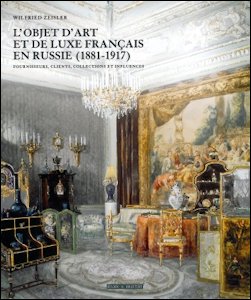

L’Objet d’art et de Luxe Français en Russie

(1881-1917): Fournisseurs, Clients, Collections et

Influences by Wilfred Zeisler, 2014

Fabergé enthusiasts will not be disappointed. There is much to surprise and amaze, and plenty of new material for those who know the subject all too well. Geoffrey Munn outlines the story of Wartski’s early acquisitions of Fabergé from the Soviet Government between 1927 and 1933 with new provenances for some of these objects revealed for the first time. Each genesis of a succession of Fabergé publications is described in detail, and so too are the Wartski exhibitions which were planned to coincide with them. The book is not just about Wartski, but it is also a biography of its clientele, complete with European royalty and a rainbow of individuals of theatrical fame. A collage of animated photographs by Cecil Beaton and the Earl of Snowdon of Wartski’s customers, and Fabergé collectors – Queen Mary, Frank Sinatra, Yul Brynner, Barbra Streisand, and Joan Rivers – come alive with anecdotes and objects from their collections. Readers with just a passing interest in Fabergé will enjoy learning about a “bonfire of vanities”, including Renaissance jewellery, the Russian Crown jewels, 18th century gold boxes, Castellani, Lalique, and Fabergé’s greatest competitor of all, Cartier in Paris. (Interview with Christel McCanless)

“Eggs-travagant Fabergé: Eggs Fit for Dynasty, Holding History and a Surprise” in Sense: Eclectic Intellect for the Soul, March 2014, 24-31. A selection of Fabergé eggs from the Post and Pratt Collections in Washington (DC) and Richmond (Virginia) are shown in lavish photographs. (Courtesy Jeanne O’Connell)

von Solodkoff, Alexander. The Jewel Album of Tsar Nicholas II and A Collection of Private Photographs of the Russian Imperial Family,1997. Review of a long out-of-print title by Paul Gilbert, publisher of Royal Russia News, illustrated with a few of Nicholas II’s jewel sketches.

Zeisler, Wilfried. L’Objet d’art et de Luxe Français en Russie (1881-1917): Fournisseurs, Clients, Collections et Influences, 2014. In French.

Book focuses on French luxury goods in Russia during the reign of Alexander III and Nicholas II, and explores the relationship between French firms (including silversmiths, jewelers such as Cartier, Chaumet, Boucheron, Keller, Lalique, Mellerio, etc.) and their Russian competitors or partners like Fabergé. Customers of the Fabergé firm, for example, Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna, are considered as well.

Imperial Treasures in Old Videos (Reprinted from Romanov News, No. 83, February 2015, courtesy of Paul Kulikovsky, publisher)

Russian Crown Jewels (1926) Video

Jewels! (1933) Video

The Tsar’s Egg (1950) Video

The Queen’s Treasures (1962) Video

Tsar’s Dinner Service Auction (1967) Video

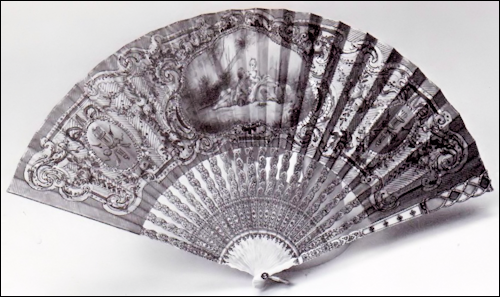

Fans with Fabergé Guards Galore!

Fan enthusiast Thomas DeLeo shared two new finds for the ongoing Fabergé Fan Treasure Hunt.

In a newsletter of the Fan Circle International, a group formed in 1975 to promote interest in and knowledge of all aspects of the many varieties of fans, DeLeo discovered Christie’s New York (October 19, 1981) sold lot 336 as “the most expensive fan of the season for a princely sum $18,000”. Previously, the fan with a Mikhail Perkhin enameled and jeweled guard realized SFr 10,000 (Christie’s Geneva, April 27, 1977, lot 407). Based on the CPI Inflation Calculator using the 1981 sale price the 2015 value might be ca. $46,000. Where is the fan now? Contact: Christel McCanless

Silk Fan with a Painted Amatory Scene with Pierced and Painted Ivory Sticks,

and Pale Blue, Rose, and White Enameled

and Gold Jeweled Guard by Mikhail Perkhin, Active 1896-1903

(Courtesy Christie’s)

Brussels Lace Fan with Tortoise Shell Guard Marked Mikhail Perkhin on the Loop

(Eberle, Catalog #395)