Fabergé Forum 2016 Featuring the McFerrin Collection

November 3-4, 2016

Houston Museum of Natural Science, Texas

The Dorothy and Artie McFerrin Collection has grown to over 600 objects!

Speakers Confirmed from Finland, Russia, USA

Details for the event will follow ASAP.

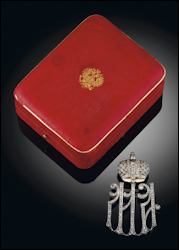

Fabergé Platinum and

Multi-colored Diamond

Flower Brooch

(Courtesy McFerrin Collection)

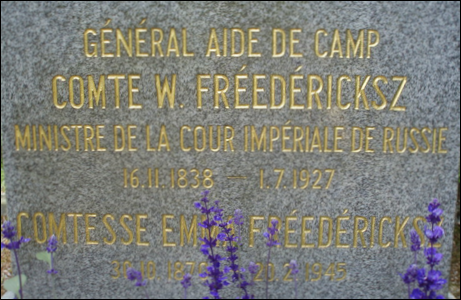

Baron Vladimir Borisovich Freedericksz

(1838-1927), Russian Statesman

(Wiki)

Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm and Tatiana Cheboksarova at the Gravesite of Count Freedericksz in Grankulla, Finland.

The Later Title of Count Was Bestowed in 1913.

(Photographs by Galina Korneva)

Fabergé Invoice for the Freedericksz Casket

(Source RGIA)

Coat of Arms of Baron Vladimir Borisovich Freedericksz (1838-1927)

(Wiki)

1 Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm in her 2005 reference volume, The Russian Imperial Award System during the Reign of Nicholas II, 1894-1917, lists in detail the recipients as well as the jewelers and makers of the these coveted awards including the highest orders – St. Andrew, St. Catherine, St. Vladimir First Class, St. Alexander Nevskii with diamonds and the White Eagle with diamonds, and the diamond portrait badge. For this article, she shared specific details from the Count’s Service Record for 1917: After 61 years and 11 days of service he had the right to a base salary of 9.000 rubles plus “˜table money’ of 9.000 r., a supplementary salary of 18.868 r. (probably for seniority in office), and 4.000 r. for handling the Domains. The authors appreciate her assistance.

2 RGIA. Fond 468. Inv. 14, File 3186.

3 RGIA. Fond 472. Inv. 41, File 42.

Additional information about the life of the Baron is in Margarita Nelipa, “Servant to Three Emperors. Count Vladimir Borisovich Freedericksz”. Royal Russia, #7, Winter 2015, pp. 41-74.

Grand Duke George Mikhailovich and His Family at Kharaks in the Crimea

(Courtesy Christie’s, New York)

Located close to the emperor’s palace at Livadia and to Ai Todor, the palace of Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich and Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna, Kharaks hosted numerous members of the imperial family and St. Petersburg society. Grand Duchess Marie recalled in her memoirs that Nicholas II “came two or three times a week, when living at Livadia, to dine with us. The Empress sometimes came too … [He] would bring his two oldest daughters, Olga and Tatiana [and he] always told me he loved coming to us because he could be himself.” (Grand Duchess George, A Romanov Diary: The Autobiography of H.I. & R.H. Grand Duchess George, G.N. Tantzos and M.A. Eilers, ed., New York, 1988, p. 133). The guest book from Kharaks, which survived in the family’s collection, records the signatures of hundreds of visitors, including the emperor and his family, as well as the Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna and Grand Duchesses Xenia and Olga Alexandrovna.

An original photograph album of Kharaks, also in the family’s collection, depicts a comfortable family home where numerous accessories and photograph frames covered the surfaces of furniture in many of the rooms. A photograph prominently displayed on the mantelpiece of the salon clearly shows a large Fabergé silver and wood triptych frame with original photographs of Grand Duke George and the two princesses. (Christie’s, New York, May 20, 2015, lot 48, illus. A. in this text) Other works by Fabergé, while not visible in situ, must have been given to the family by their esteemed guests during their visits. A Fabergé silver and pink enamel heart-shaped photograph frame, enclosing an original photograph of Princess Nina, (Christie’s, New York, May 20, 2015, lot 32) was purchased by Nicholas II from Fabergé’s St. Petersburg branch on July 16, 1907, just prior to one of his many visits to Kharaks. The frame was almost certainly a personal gift to the family which the emperor brought with him on his visit.

(A) Silver and Wood Triptych Photograph Frame,

Workmaster Antti Nevalainen, 1899-1904

(Courtesy Christie’s, New York)

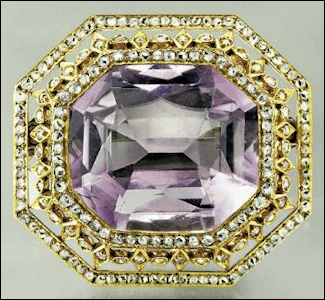

(B) Gold, Diamond, and Amethyst Brooch, Workmaster August

Holmström, Circa 1898

(Courtesy Christie’s, New York)

(C) Two-color Gold, Silver and Enamel Photograph Frame,

Workmaster Viktor Aarne, Circa 1901

(Courtesy Christie’s, New York)

(D) Gold and Enamel Photograph Frame,

Workmaster Michael Perkhin, Circa 1901

(Courtesy Christie’s, New York)

Perhaps the most striking object in the collection is a Fabergé gold and enamel heart-shaped mechanical photograph frame (Christie’s, New York, May 20, 2015, lot 63, illus. D.) The frame contains original photographs of Grand Duke George, Grand Duchess Marie and baby Nina. The original purchase has not been traced, but judging from Nina’s photograph it appears to date to 1901, the year of her birth. Made in the workshop of Michael Perkhin, the frame has functioning windows which cover each photograph. The windows are operated by a push-piece and powered by an intricate mechanism located inside the back cover of the frame. The design and construction undoubtedly were inspired by the surprise in the Imperial Pansy Egg (1899), a similar enamel heart-shaped photograph frame with functioning windows, also made in Perkhin’s workshop.

As with so many members of the imperial family and the aristocracy, the lives of Grand Duke George Mikhailovich and his family were torn apart by the Russian Revolution. In the summer of 1914, Grand Duchess Marie and the two princesses left Russia for England. Xenia had been suffering a respiratory illness, and on doctor’s orders they left for the “bracing air” of Harrogate. The outbreak of World War I prevented them from returning home safely, and they were forced to settle in Harrogate and London. Grand Duchess Marie established hospitals in Harrogate which cared for wounded soldiers over the course of the next five years. In recognition for her service, she was awarded the Royal Red Cross by King George V. Neither she nor the princesses would ever return to Russia.

In June of 1917, as the Revolution intensified, Grand Duke George was granted permission to travel to Finland. He remained there until April of 1918, when he was arrested, returned to Petrograd, and then exiled to Vologda. In July, he was sent to Petrograd, where he was imprisoned along with his brother Grand Duke Nicholas Mikhailovich and their cousin Grand Duke Paul Alexandrovich. In January 1919, the three grand dukes were executed by a Bolshevik firing squad. Grand Duchess Marie learned of her husband’s death in a newspaper on February 4, 1919, confirmed the following day by a wire from Finland. “It is useless,” she recalled, “to try to describe the agony I went through having to tell this news to my poor girls …” (Grand Duchess George, op cit., p. 239).

Many of the family’s belongings were left behind at Kharaks. From 1918 to 1919, the Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna, who had fled south, lived at Kharaks. In April 1919, the HMS Marlborough, under orders of the British Royal Navy, arrived in the Crimea to evacuate the Dowager Empress and other members of the Russian Imperial Family who were staying in the area. One of the last pages of the Kharaks guest book records the signatures of the Dowager Empress, Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna and her children, Prince Felix Yusupov, and the captain of the HMS Marlborough, C.D. Johnson. Some of the family’s most treasured belongings, including the objects by Fabergé known to have been at Kharaks, presumably were removed, perhaps on the orders of the Dowager Empress, brought on board the ship, and subsequently delivered to Grand Duchess Marie in England.

Princess Nina went on to marry Prince Paul Alexandrovich Chavchavadze (1899-1971) in London. Prince Paul was descended from the Chavchavadze family of Georgia and in a direct line from the last King of Georgia, George XII (1746-1800). The couple had one son, David (1924-2014), and in 1927 the young family moved to the United States, living first in New York and eventually moving to Massachusetts. The family’s collection descended from Nina to David, who served his country during World War II and later as a CIA (Central Intelligence Agency) case officer during the Cold War.

Princess Xenia Georgievna married twice, first to William Bateman Leeds (1902-1971), and then to Herman Jud (1911-1987). She lived with William Leeds on the North Shore of Long Island and had a daughter, Nancy Helen Marie Leeds, who married Edward Judson Wynkoop, Jr. Another part of the family’s collection descended in Princess Xenia’s family. Among these pieces were several exceptional objects by Fabergé, including a triptych frame enclosing portraits of Grand Duchess Marie and the two princesses; a frame commemorating the 10th wedding anniversary of Grand Duke George and Grand Duchess Marie and enclosing portraits of the grand duke and the two princesses; and a frame enclosing a portrait miniature of Grand Duchess Marie and Emperor Alexander III. As the daughter of Xenia, Mrs. Wynkoop inherited the collection, which upon her death in 2006 was donated to the Middlebury College Museum of Art in Vermont.

With the emergence of the objects by Fabergé which descended in Princess Nina’s family, the collection of Grand Duke George Mikhailovich and his family is in a sense reunited. The objects not only document the life of this one branch of Russian Imperial Family, but they also open a new chapter in the important history of the imperial family’s patronage of the Fabergé firm.

And then there are the stories. After all, every acquisition has a tale associated with it. A few are quite simple and direct: “Yes, I bought this object at Wartski 15 years ago when I was in London”, or “In 2003, the hammer came down at Christie’s and I could not believe I was the high bidder.” In other instances, the hunt is much more complicated, dotted with intrigue and uncertainty. The thrill of the experience lies with the competition and the camaraderie, more often than not within our own ranks! Education is the ultimate achievement here, however. The excitement of finding a new tidbit of information and adding a provenance detail to an object which has been yours for a while is wonderful, especially if it is your bell push or cigarette case identified in an old auction catalog. Perhaps some new document is unearthed in the St. Petersburg archives indicating when and by whom your photo frame was originally purchased. Regardless of the source, there is great satisfaction in advancing the knowledge and understanding of both the object, and its time and place in history.

(A)

(B)

(C)

(D)

(E)

(F)

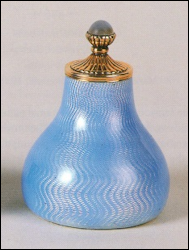

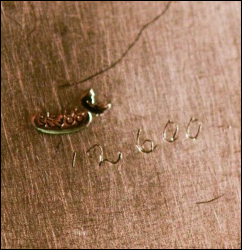

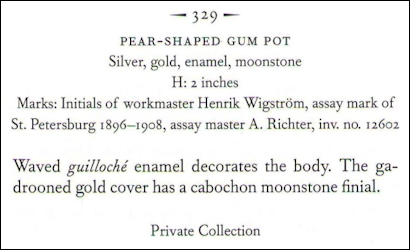

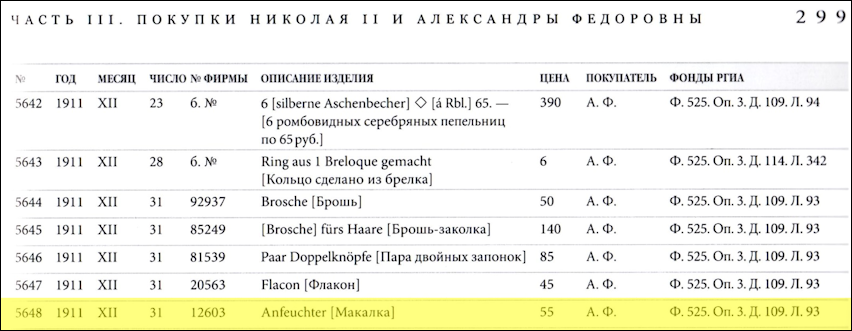

- A. and D. Pale-green Gum Pot with Stock Number 12600

- B. and E. Mauve Gum Pot with Stock Number 12601

- C. and F. Sky-Blue Gum Pot with Stock Number 12602

(A-B, D-E. Courtesy Kirsch Collection; C and F. von Habsburg, Géza, Fabergé in America, 1996, p. 294, illus. 329)

An inquiry about a possible stock number on the dealer’s piece led to the next discovery – the two objects were numbered sequentially, 12600 (pale-green) and 12601 (mauve). The attraction was irresistible to me. Despite trying to maintain a tight budget and adding pieces carefully for variety in my collection, the thought of reuniting two fine objects, which had been separated for over 100 years and countless miles, was just too compelling. So now they are back together again, as I imagine they were at one time sitting on a work bench in Wigström’s shop. Ironically, a triplet in the stock number sequence (12602) is a sky-blue gum pot (illus C. and F.) somewhere in a private collection, but where? And then there appears to be a quartet of sequentially numbered gum pots! Stock number 12603 is cited in a chronological list of purchases made in 1911 by Empress Alexandra Feodrovna:

Fabergé Items of Late XIX – Early XX Century in the Collection of the State Museum of Pavlovsk, 2014, p. 299

An easy-to-find quick index to each egg has been added.

Coincidences during the preparation of this newsletter advance our knowledge about Faberge objects. The Faberge Research Newsletter, Winter 2015, states “a house museum honoring Vasilii Ivanovich Zuiev (b. 1870), miniature artist-court painter employed by the Fabergé firm in 1908, was opened in the village of Cherdakly, Ulyanovsk region of Russia.” Through the generosity of the curatorial staff of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts two miniatures (each only 1 9/16 in. high) from the 1903 Peter the Great Egg photographed during the museum’s conservation project are shown below with Zuiev’s signature, В. Зуевь.

1903 Peter the Great Egg by Fabergé

(Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Bequest

of Lillian Pratt, Photo: Katherine Wetzel

© Virginia Museum of Fine Arts)

![Miniature of Peter the Great, signed on right, В. Зуевь [court miniaturist, Vassilii Ivanovich Zuiev (1870-after 1931)] watercolor, ivory. (Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Bequest of Lillian Pratt, Photo: Travis Fullerton © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts)](http://fabergeresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/spring16nl21.jpg)

Miniature of Peter the Great, signed on right,

В. Зуевь [court miniaturist, Vassilii Ivanovich Zuiev

(1870-after 1931)] watercolor, ivory.

(Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Bequest of Lillian Pratt,

Photo: Travis Fullerton © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts)

1903 Peter the Great Egg by Fabergé

(Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Bequest

of Lillian Pratt, Photo: Katherine Wetzel

© Virginia Museum of Fine Arts)

![Miniature of Emperor Nicholas II, signed on left, В. Зуевь [court miniaturist, Vassilii Ivanovich Zuiev (1870-after 1931)] watercolor, ivory. (Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Bequest of Lillian Pratt, Photo: Travis Fullerton © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts)](http://fabergeresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/spring16nl23.png)

Miniature of Emperor Nicholas II, signed on left,

В. Зуевь [court miniaturist, Vassilii Ivanovich Zuiev

(1870-after 1931)] watercolor, ivory.

(Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Bequest of Lillian Pratt,

Photo: Travis Fullerton © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts)

In Russia after the Crimean War (1853-1856), cigarette and cigar smoking became more and more fashionable (previously tobacco was only chewed, snuffed and smoked in pipes or cigars). With the invention of the rather expensive safety match in 1840’s, table lighters with a lighter fluid compartment and a wick began to be used for the popular pastime of smoking. Whimsical and realistically modeled animals combined with a functional object made out of silver and silver gilt were Fabergé’s creative answer to the demands of this new market. The central body of each animal is the lighter fluid compartment with the wick accessible to the outside, so guests were able to light their choice of cigarettes or cigars. Usually the head of the animal is hinged to replenish the lighter fluid. A multi-step process to create Fabergé table lighters from a variety of animals with an emphasis on their charming personalities began with a sketch followed by a wax, plaster, or wood model made by a sculptor. Then a mold was made from the model, and the individual pieces cast in silver. After joining them, the final touch was applied by artisans using chasing and engraving to represent fur, hide, or feathers. A further discussion is found in the essay, “Fabergé Silver Animals” by Alexander von Solodkoff in von Habsburg, Fabergé: Imperial Craftsman and His World, 2000, 102-108.

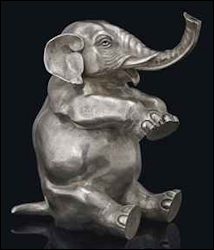

A small selection of table lighters with engaging personalities from the Julius Rappoport Workshop and the First St. Petersburg Silver Artel recently on the auction market range in size from 3 8/7- 6 1/4 in. long, 4 3/8 in. high, and 5 1/8 in. wide. Links in the credit lines to enlargements and zoom images below each photograph are fun to explore. How is the lighter fluid added? Where is the wick located? How is ornamental chasing and engraving used?

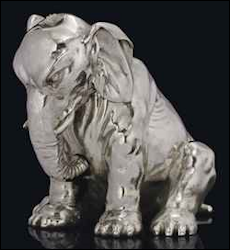

Seated Elephant Table Lighter, Hinged Head

Opens the Lighter Fluid Compartment, Stock

#1613, Price Realized: $57,075

(Courtesy Christie’s London, June 3, 2013,

Lot 234; also Sotheby’s Geneva,

November 21, 1991, Lot 417, SFr 38,500)

Seated Elephant Table Lighter, 4.5 in./11.5 cm

high, 27.37 oz./851.2 gr. of silver, $75,910

(Courtesy Courtesy Christie’s London,

June 3, 2013, Lot 235)

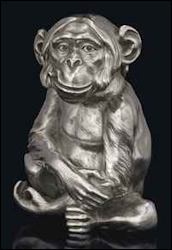

Smoking Monkey Table Lighter with

London Import Marks for 1911

(Rappoport retired in 1908), Stock #

Possibly 1165 or 3165, $57,075

(Courtesy Christie’s London,

June 3, 2013, Lot 233; also

Sotheby’s Geneva,

November 15, 1990,

Lot 223, SFr 41,800)

Rhinoceros Table Lighter, Wick in the Hollow Horn,

Stock Number 9330, GBP 81,700

(Courtesy Sotheby’s London: June 3, 2014,

Lot 652, also Christie’s New York, April 19, 2002,

Lot 202, $107,550)

Lizard Table Lighter, Hinged Head

Reveals the Lighter Fluid

Compartment, Tongue is the Wick,

Soviet Control Marks, $18,750

(Courtesy Sotheby’s New York,

October 14, 2015, Lot 38)

Bear Table Lighter, Lower Foot Reveals the Lighter

Fluid Comparment, Provenance: Estate

of Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester

(1900-1974), $56,700

(Courtesy Christie’s London, Novemember 25, 2013,

Lot 224; also Snowman, Carl Fabergé, Goldsmith

to the Imperial Court of Russia, 1979, 40.)

Chimpanzee Table Lighter, Stock

Number 14569, $168,000, Provenance:

Princess Maria Gabriella of Savoy

(Courtesy Christie’s London,

June 27, 2007, Lot 19; also

Christie’s Geneva, May 12, 1980,

lot 233, SFr 9,000)

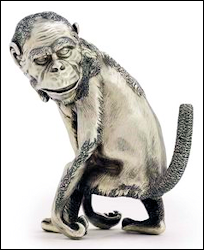

Seated Baboon Table Lighter, First

St. Petersburg Silver Artel

(Succeeded Rapppoport, Active

1908-1911), Marked and Retailed

by Fabergé, $58,750

(Courtesy Christie’s New York,

October 19, 2001, Lot 90)

Lighter Fluid Compartment

Hinges on the Seated Monkey

Table Lighters

(A La Vieille Russie

Christmas Catalog, 2014, p. 61)

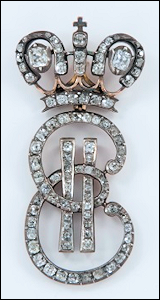

During a peer review of my cipher collage, Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm and Timothy Adams both with years of experience in the jewelry trade, taught me about open and closed-back settings on jewelry. From Finland Tillander-Godenhielm wrote:

Cipher EII (1762-1796) of Empress Catherine II

Cipher A (1828-1855) of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna (1798-1860), Numbered III of 14 Presented

Cipher MA (1894-1917) of Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna (1847-1928) and Empress Alexandra Feodorovna (1872-1918),

Carl Hahn Workshop, No. 53 presented to Anna Vladimirovna Osten- Sacken Coburg in May 1896.

(All Photographs Courtesy McFerrin Collection)

Cipher MA (1894-1917) of Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna (1847-1928) and Empress Alexandra Feodorovna (1872-1918), Made in 1913 by the

Carl Blank Workshop. Provenance: Baroness Maria “Marousia” Langhoff (1893-1975), daughter of August Langhoff (1856-1929), Minister of State Secretary

of the Grand Duchy of Finland in St. Petersburg.

(Courtesy Court Jeweler W.A. Bolin, Stockholm, Sweden)

Fabergé – Tsar’s Court Jeweler and the Connection to the Danish Royal Family

One hundred loans from members of the Danish royal family, who through family ties to the Russian emperor and his family, inherited these objects. They will be shown along with Fabergé from the King’s Collection at Amalienborg.

Exhibition Catalog Published! Venue with more than 150 items from the Pavlovsk State Museum collection in Russia shown at Turku Castle, Turku, Finland, December 11, 2015 – April 3, 2016, then moves to South Karelia Museum in Lappeenranta, Finland, April 29 – October 2, 2016. Imperial Gifts from Pavlovsk Palace

Ludmila Budrina, Ekaterinburg Museum of Fine Art (Russia) contributed an article to the exhibition catalog in four languages (English, German, Russian, Chinese) for the Heroes. History in Ural Stone Carving venue opening at the Liechtenstein National Museum in Vaduz on March 23, 2016. Her contribution is entitled, Five Centuries of Three-Dimensional Mosaic: Predecessors, Contemporaries, Successors of Carl Fabergé. Additional book authors include Alexander Shmotiev, Tatiana Muntian, and Serguey Shokarev.

Tatiana A. Tutova, who works in the Moscow Kremlin Museum’s Archives, published her research in the book entitled, The Fate of Palace Treasures of the Russian Imperial Court. The Inventories of a 1922 Special Commission in the Moscow Kremlin. Detailed information about 95,000 items from the Imperial Treasures with full inventory lists of the objects contains comments comparing different sources. The two-volume set of text and commentary enables researchers to re-establish the history of many Imperial objects and traces the whereabouts of them after 1922. Included also are short biographies of individuals who participated in the work of the Commission, and several illustrations. Published in Russian by the Moscow Kremlin Museums in 2015. (Information contributed by Irina Polynina, Moscow)

Turku and Lappeenranta

(Finland)

Liechtenstein National Museum

(Vaduz, Liechtenstein)

Kremlin Museum in Moscow

(Russia)

Georgia Museum of Art, Athens, Georgia

(USA)

Such an Unsafe Throne: Queen Victoria, Russia and the Romanovs

Galina Korneva (Russia) September 27, 2016 Society of Jewellery Historians, London

Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna’s Contacts with Paris Jewellers and Her Collection of Treasures

Russian archival information, only recently available to specialists, will be presented about jewel and silver objets d’art in the collection of Grand Duke Vladimir (1847-1909) and his wife Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna (1854-1920). The couple acquired the treasures from the best known Parisian jewelers – Chaumet, Falize, Boucheron, Cartier, Aucoc, etc.

Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm (Finland) November 1, 2016 Georgia Museum of Art, Athens, Georgia

The Russian Imperial Award System

A private collection on extended loan relating to the Romanov dynasty which contains military orders, medals, badges, paintings, and more is on view from September 3 – December 31, 2016. Special programs planned are a museum symposium on September 23-34, 2016. Dr. Tillander-Godenhielm, author of the book The Russian Imperial Award System during the Reign of Nicholas II, 1894-1917, during her November lecture will acquaint the audience with the historical background of these objects.

Kieran McCarthy (United Kingdom) November 22, 2016 Society of Jewellery Historians, London

Previously unknown details about the London Fabergé branch in existence from 1903-1917 and its customers will be unveiled after years of research into archival records. McCarthy’s book, Fabergé in London published by the Antique Collectors’ Club, available Autumn 2016.

Timothy Adams and Irina

Polynina Studying the

Madonna Lily Egg for the

1989-90 San Diego Museum

of Art Exhibition, Later Shown

in St. Petersburg, Russia.

(Photograph Courtesy

Timothy Adams)

Irina Polynina with

George W. Terrell, Jr.

at the 2016 Birthday

Celebration in Moscow

(Photograph Courtesy

Ulla Tillander-

Godenhielm)

Nuna Alekian (Russia): 10th anniversary of the newsletter is a big step! Congratulations!

Géza von Habsburg (USA): The Newsletter is as good as always! Congratulations!

Jennifer McFerrin Bohner (USA): We appreciate all the research and help you offer this community. ![]() [The McFerrin Collection on view at the Houston Museum of Natural Science in Texas, was chosen as the host site for the Fabergé Forum 2016 on November 3-4, 2016.]

[The McFerrin Collection on view at the Houston Museum of Natural Science in Texas, was chosen as the host site for the Fabergé Forum 2016 on November 3-4, 2016.]

Representing a very dedicated docent cadre at the Houston Museum Rich Hutting (USA) writes:

Gherkin Perfume Flask

(Courtesy McFerrin Collection)

Rich Hutting Teaching with His

Magnifying Glass, Unfortunately

Not by Fabergé!

(Photograph Christel McCanless)

Fabergé Russian-Style Kovsh, the Centerpiece

for the Fall 2016 Virginia Museum of Fine Arts Venue

(Courtesy Virginia Museum of Fine Arts)

Vivian Alexander Collection – Duchess of Marlborough, Renaissance, Lilies

of the Valley, Coronation, and Cockerel Eggs. Géza von Habsburg upon

seeing my Lilies of the Valley Egg noticed it had a stand with three legs

instead of the four on the original Fabergé egg. He told me the original

Fabergé Lilies of the Valley Egg was awarded Best of Show at the 1900 World’s

Fair in Paris, and the judges at the fair thought the piece was perfect except

it would had been even better, if Fabergé had used three legs instead of four.

(Caption Details Courtesy of the Author)

Enameling, the early years: In 1993, I learned about an enameling process called rosin enamel which added color to jewelry. The learning curve was steep. I struggled for two years to learn and then perfect the technique with an added challenge on how to apply enamel to a double-curved surface (an egg shell). The process was made famous by Carl Fabergé’s workmasters, whose application of translucent enamel over guilloche was one of the techniques used to add the deep luster on their enameled objects. Later I learned more during my association with Forbes, Inc., New York.

In 1997, I turned down a request from The House of Fabergé (owned by Cheseborough Ponds, Inc., New York) to sell my creations under their label. Not long after that I accepted an offer from Forbes, Inc., if “I would you be interested in selling my collection under the umbrella of The Forbes Collection?” Christopher “˜Kip’ Forbes had spotted my Lilies of the Valley Egg purse in a window on 5th Avenue earlier in the week, and wanted me to join with them in promoting their world famous original Fabergé collection under the banner of their new marketing venture named The Forbes Collection. To seal the deal they invited me on a Hudson River cruise on the Highlander yacht, one of Malcolm Forbes’ indulgences.

Call from Warner Bros., Inc.: One day while I was working on a new purse design project in my studio the phone rang and a non-southern voice said, “I am the prop master for major films produced by Warner Brothers, and I was told to contact you for an exact replica of an Imperial Fabergé Egg to be used as the feature object in an upcoming “Ocean’s” film. The specifications included the egg had to be an exact replica (enamel color, size, top opening, guilloche pattern, and overall design) of the original Fabergé Imperial Coronation Egg owned by the Forbes Magazine Collection in their house museum on 5th Avenue in New York City. We agreed on a price and a deadline. My artisans and I went to work immediately. After three months, I was satisfied with the prototype and shipped it to Hollywood, California, for approval. The producers were pleased with the work and asked me to create two more eggs and ship them directly to Rome, Italy, so filming for the 2004 American comedy heist film Oceans 12 could begin. The entire final half of the movie is about the Gang of 12 attempting to steal “The Fabergé Egg” from the Vatican Museum. The Vivian Alexander egg is prominently displayed in many scenes, since the plot calls for the gang to create a fake egg using a hologram and to swap it with the real egg. Both eggs – real and fake – are seen at the same time, but the audience does not realize there are actually my two eggs used in the scenes.

Sometime later I heard Warner Bros. had purchased an Imperial Coronation replica (not mine) from Neiman Marcus, the elegant Texas store, prior to contacting me. I asked the prop master about the purchase and what part it played in the movie. He told me when the cast was practicing for the movie they used the Neiman Marcus egg, but for the actual shooting they substituted mine. In 2004, my host George W. Terrell, Jr. invited Christel and George McCanless to join us when my egg from the numbered Coronation egg series was displayed in the Hardin Center for Cultural Arts in Gadsden, Alabama. The Detroit Museum of Art in 2012 exhibited the Vivian Alexander Coronation Egg on loan from the Warner Bros. archives.

One more adventure: Neiman Marcus bought two copies of the Vivian Alexander diamond edition Duchess of Marlborough Egg for their store in Chicago, each retailing for $30,000. Two weeks after I delivered them, they placed an order for another one. I called to ask if there was a problem. They said NO and told me what happened. A US ambassador bought the first two for his mantel piece in his home, and soon afterwards entertained Nelson Mandela, President of South Africa from 1994-1999, who admired the eggs. The ambassador gave him one, and now needed another one to balance his mantel piece display.

Linda Woytisek (USA), a three-time traveler to Russia remembers: “The Forbes Magazine Collection of Fabergé had been on display for many years in the Forbes Galleries on Fifth Avenue in New York City, but the display was never open on Saturdays or Sundays. There was a special exhibition at Sotheby’s New York after Viktor Vekselberg had agreed to purchase the collection before the auction. It was a beautiful warm day on the Valentine’s Day weekend in 2004 when my husband and I took the ferry and the ferry bus into the city, and then walked to Sotheby’s on the East Side. By the time we arrived at Sotheby’s, we were told the lines were too long and no one past a certain point would be allowed to enter. We were told to come back the next day. Believing that this was unacceptable, I pleaded and begged with Security to let us enter. I was so persistent that the Head of Security (a very nice lady) said, “Okay, follow me.’ She took us to a side entrance, put us on the LARGE freight elevator, and told us to go directly to the 10th floor. When we arrived, it was an amazing site – the most beautiful exhibition, crowds of people, and everything well organized. And there was almost complete silence as everyone was in awe at seeing the magnificent Imperial eggs. I was very happy we were allowed to enter. I do not remember when I actually “discovered’ Fabergé, but it was a long time ago. I remember attending the Love Trophies Egg auction [June 10, 1992, Sotheby’s New York, price realized $3,190,000]. I very much enjoy reading and keeping the Fabergé Research Newsletter. Many thanks!”