Lowes & McCanless, 2001

Tillander-Godenhielm, 2001

(After 2008 they are published in the FRS Newsletter, see the Index, and a complete list of the eggs is available in the Imperial Egg Chronology.)

Serpent Egg Clock

(Courtesy Cleveland Museum of Art)

Although this was already a formidable list of lenders, it was essential to attract huge publicity and, for the sake of the charity, I was hungry for more.

My journey home was (and always is!) by bus. The n°137 stopped at Clapham, and out of the blue it occurred to me that Prince Rainier of Monaco might be willing to help; however, my hopes of a loan extended to little more than a gold cigarette case or something of that sort. The glamour of the Grimaldi name in the catalogue was all I wanted and almost all I dared to hope for. The following day I dashed off a letter on Wartski notepaper and, during the ensuing weeks, completely forgot that I had written it.

Some time later, Wartski’s front door was pushed open by Virginia Gallico (widow of the famous author Paul) who introduced herself as lady-in-waiting to His Serene Highness. To my delight, she said that the Prince was willing to contribute to the Samaritans exhibition by lending a blue enamelled diamond-encrusted clock, nearly 8 inches high. As the description was hardly typical of any Fabergé clock I had ever seen, I tried to disguise my concerns about its authenticity. Virginia Gallico is an extraordinarily intuitive character and detected a shadow of doubt flicker across my face. As we all know, the road to hell is paved with good intentions and, at that moment, it seemed I had already blundered some way down it!

The only way to allay my doubts was to ask for a photograph; Mrs. Gallico promised to fax me one as soon as she returned to Monaco. The fax was still a new – and slightly mysterious – addition to Wartski’s system of communications. The following week I was standing beside it in the packing room when it painfully and slowly delivered a dark and fuzzy image. I quickly recognized the extremity of something very familiar. It was none other than the Serpent Egg Clock which Wartski sold to Stavros Niarchos for £64,103 on Christmas Eve 1972. The last time I had seen it was when I was just nineteen and had been working at Wartski for eight weeks.

During the twenty years in between, the Serpent Egg Clock had joined the company of Imperial Easter Eggs that were considered, to all intents and purposes, completely lost to scholarship. Although Prince Rainier knew the clock was by Fabergé, it was evident that Mr. Niarchos had neglected to tell him that it was one of Fabergé’s famous Imperial Easter Eggs. In 1992, the Prince’s surprise was compounded when I told him not only the true provenance of his egg but also the present value of this lovely object – it exceeded his wildest imaginings.

The Prince had asked me to go to the Palace to collect the Easter Egg in person and His Serene Highness was everything I expected. He exuded grace, wit and charm in a curiously English manner. The Serpent Egg Clock was standing in a modern rectangular vitrine with all manner of objects of vertu, some of which I recognized as coming from Wartski. After the initial excitement of seeing the Egg again had abated, the Prince gave me a lengthy tour of the Palace and we went from floor to floor in an old fashioned lift accompanied by his favourite dog.

The conductor of this extraordinary sequence of events was Virginia Gallico who, with her perfect sense of diplomacy, had suggested delicately that I “bring black-tie to Monaco just in case.” That afternoon I answered a telephone call in my hotel asking if I might care to join the Prince at the Opera. There I saw Marie Stuarda by Donizetti from the splendour of the Royal Box!

The following day I was sitting in a helicopter with the Easter Egg tucked under my seat. As we circled Monaco, on the first step of my journey back to London, I was almost sick with excitement.

Thanks to the Prince’s kindness, the Egg was the star of the Samaritans exhibition, Fabergé from Private Collections. The press were delighted with the story of its rediscovery … and the charity was thrilled with the very considerable proceeds it generated.

Revised Timeline © Annemiek Wintraecken

The Blue Serpent Clock Egg is currently on view in an American museum for the first time ever. Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm, Christel Ludewig McCanless and I discussed it on email, and Dr. Tillander-Godenhielm asked for my thoughts on the Egg and its place in the chronology published in Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs (1997) by Tatiana Fabergé, Lynette G. Proler and Valentin V. Skurlov.

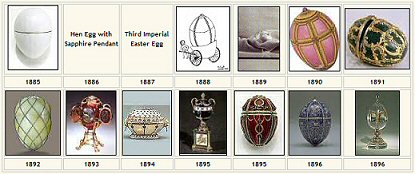

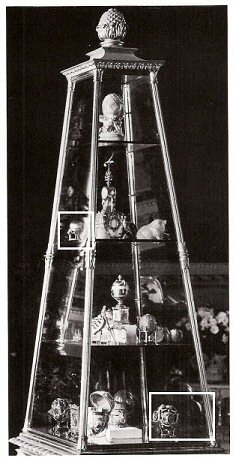

We both agreed that the Blue Serpent Clock Egg perhaps was dated a little too early in the egg timeline, since the Fabergé workshops probably were not ready in 1887 for such a sophisticated egg. We discussed the 1902 von Dervis exhibition (img1) in which the Egg was clearly visible in the centre of the showcase. Dr. Tillander-Godenhielm asked if I could find another plausible place in the timeline and she sent me some high resolution images of the showcases with Fabergé items belonging to the Empresses Maria and Alexandra Fyodorovna.

von Dervis Exhibition Case

The Answer:

There are four parts to my hypothesis:

- The Blue Serpent Clock Egg is the egg belonging to the Fabergé invoice of the year 1895.

- The 1895 Twelve Monogram Egg is the same egg as the missing 1896 Alexander III Portraits Egg.

- For the year 1887, a new (now missing) Imperial Easter Egg has emerged. (Ed. Note: Discovered in 2011, Parke-Bernet, New York, March 6-7, 1964, auction catalog.)

- A Bonus Discovery.

1. The Blue Serpent Clock Egg is the 1895 Egg

Searching for another place in the Fabergé Egg timeline for the 1887 Blue Serpent Clock Egg, I discovered the invoice of the 1895 Twelve Monogram Egg also fits the Blue Serpent Clock Egg. The invoice of the 1895 Egg reads:

I wondered whether the 1895 Twelve Monogram Egg really was a Louis XVI style egg, and I asked Dr. Tillander-Godenhielm, if both eggs belonged to the Louis XVI style. She responded the Blue Serpent Clock Egg is in the Louis XVI style and, although the Twelve Monogram Egg has elements of that style, the egg is not. The first piece of the puzzle was in place. Other pieces are:

I began thinking about the amount of time Fabergé had to make this egg, in view of the death of Tsar Alexander III on November 1, 1894, and I concluded the Fabergé workshop probably started right after Easter in April 1894 on Maria Fyodorovna’s egg. Franz Birbaum, Fabergé’s head workmaster, states in his memoirs:

So, if one of the two 1895 eggs was to be a relatively simple one, it could not have been the Dowager Empress’ egg; it was the egg for Tsarina Alexandra for which there was barely half a year to make it. Based on the above, I concluded the Fabergé invoice of the 1895 could be the invoice of the Blue Serpent Clock Egg.

2. The Twelve Monogram Egg is the missing 1896 Alexander III Portraits Egg

Since the Blue Serpent Clock Egg could be the 1895 egg, I had to find another place for the egg now in that position, for there could not be two 1895 eggs for the Dowager Empress. After reading all the invoices again, I found the invoice of the 1896 (missing Alexander III Portraits) Egg also fits the Twelve Monogram Egg:

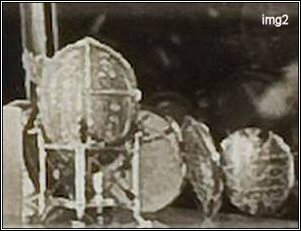

The Twelve Monogram Egg is visible in Tsarina Maria Fyodorovna’s case, third shelf from the top, possibly with miniatures (img2).

Twelve Monogram Egg

There simply seems to be no other explanation then that the Twelve Monogram Egg and the missing Alexander III Portraits Egg are one and the same egg, namely the 1896 Egg. Consequently, the place in the timeline for the 1895 Egg is available for the Blue Serpent Clock Egg.

So far I found the answer to the question Dr. Tillander-Godenhielm had asked. As so often happens when questions are answered, new questions arise, and my research was no exception.

3. For the year 1887, a new (now missing) Imperial Easter Egg has emerged (Ed. Note: Discovered in 2011, Parke-Bernet, New York, March 6-7, 1964, auction catalog.)

The Blue Serpent Clock Egg now being the 1895 egg, there is a vacancy for an egg belonging to the year 1887. What egg could that be and what do we know about it? What happened to it? Does it still exist? Can it be found?

Since the showcase of the Dowager Empress is only partly visible, I can only speculate about the objects that are seen. Possibly eggs are hidden from view behind bigger objects on the lower three shelves.

There is, however, an object that could be an egg on the left of the second shelf from the top. Could this “round object” be the new unknown and missing Fabergé Easter Egg (img3)?

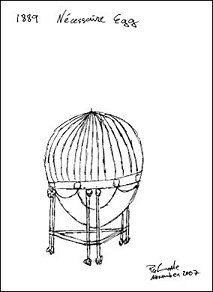

1887 Third Imperial Easter Egg

“Gold egg with clock with diamond pushpiece on gold pedestal with 3 sapphires and rose-cut diamond roses” [7]

“Gold egg with clock on diamond stand (?) on gold pedestal with 3 sapphires and rose-cut diamonds” [8]

This “object” is discussed below (November 2007) by Anna and Vincent Palmade as possibly being the missing Nécessaire Egg. Soon after this was published, Kieran McCarthy of Messrs. Wartski shared an archival photograph (see below April 2008 Anniversary Edition) of the Nécessaire Egg contradicting this finding.

A Bonus Discovery

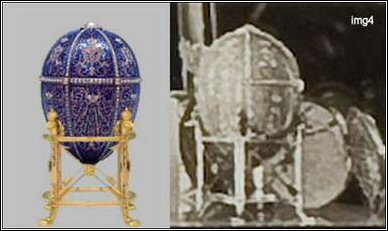

The “Twelve Monogram Egg/missing Alexander III Portraits Egg” is seen in the von Dervis exhibition in a stand now associated with the Pelican Egg. Speculating on this find, I made a computer composition of modern photographs of the “Twelve Monogram Egg/missing Alexander III Portraits Egg” and the Pelican Egg stand.

Shown below is the first egg in the second egg’s stand, and then compared to the original detail on the 1902 von Dervis photograph (img4). I was sure that it was the same stand. Whether the stand was made for the Egg it is seen in, I cannot tell. The invoices in Fabergé/Proler/Skurlov (1997) give no information on a stand, nor for the “Twelve Monogram Egg/missing Alexander III Portraits Egg”, or for the 1898 Pelican Egg. [9]

Twelve Monogram Egg in 1902 in the Von Dervis Case

Confiscated Treasures with an Enlargement of the Pelican Egg with Stand

Acknowledgements

My thanks to Fabergé author and scholar Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm for asking this challenging question and clarifying the different Louis styles, to my Fabergé friend and art historian Timothy Adams for helping me identify the stand, and to Christel Ludewig McCanless for being my friend and never tiring “Fabergé tutor”.

References

[1] Fabergé, Tatiana, Proler, Lynette G. and Valentin V. Skurlov. The Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs, 1997, 240. (invoice 1094, March 31 purchase).

[2] von Habsburg, Géza, and Marina Lopato, Fabergé Imperial Jeweler, 1993, 73.

[3] Lowes and McCanless, Fabergé Eggs: A Retrospective Encyclopedia, 2001, 23 (Background Notes).

[4] von Habsburg, Géza, and Marina Lopato. Fabergé: Imperial Jeweler, 1993, 453.

[5] Fabergé/Proler/Skurlov, 123, 241.

[6] Ibid., 94, 236.

[7] Ibid., 98.

[8] Ibid., 256 (item 682/1548).

[9] Ibid., 135, 242 (item 5240/1845).

Image Credits img1, img2, img3 – Archival Photographs, Archives Tatiana Fabergé (Courtesy Dr. Tillander-Godenhielm)

img4 – Composition of images available on the Internet (image editing by the author)

img5 – Archival Photograph available on the Internet

Blue Serpent Egg Clock

(Photos © Christel McCanless)

From the Lowes and McCanless, Fabergé Eggs: A Retrospective Encyclopedia I knew the egg was shown at the 1902 von Dervis exhibition in St. Petersburg, and then in 1953 and 1992 at Wartski in London. Between the two London exhibitions its whereabouts were somewhat mysterious.

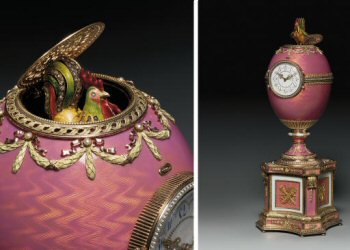

In New York I was going to be present for the unveiling of the 1887 Imperial Blue Serpent Egg, given to the late Prince Rainier III of Monaco in 1974 to honor his Silver Jubilee, the 25th anniversary of his accession to the Grimaldi throne. His son, Prince Albert II is sharing his family treasure with visitors to the Cleveland Museum of Art venue, Artistic Luxury: Fabergé, Tiffany, Lalique.

That October morning as the velvet drape dropped from the glass case someone behind me remarked, “It is so small!” The egg is 7 1/4 inches (18.3 cm) tall – the translucent royal blue enamel in contrast to the opalescent white enamel is stunning. The 1902 Duchess of Marlborough egg in the same style is 9 1/4 inches tall. The Honorable Consul General, Maguy Maccario-Doyle, summarized the historical happenings eloquently when she spoke of the “magic and mystery of the Fabergé Egg Clock”.

For Fabergé scholars new details have emerged about the history of the egg – Stephen Harrison, curator of the Cleveland Museum, discovered the Blue Serpent and the Danish Palaces Eggs were first shown at the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris, France. The Blue Serpent Egg belonged to Greek shipping tycoon Stavros Niarchos, before it became Princess Grace’s personal favorite and after her death was rarely shown to anyone by order of her husband, Prince Rainier.

My favorite moment came when the glass case was removed for a photo-op and I captured the two photos shown above … and best of all, I no longer have to keep the secret about the Imperial Blue Serpent Egg and I can share my joy of having seen it at the New York unveiling with other Fabergé enthusiasts. (To view the Forbes.com video movie of the unveiling ceremony, readers are advised to wait for the major event after two ads, or see still photos).

Congratulations to the staffs at the Cleveland Museum of Art and Consulate General of Monaco for hosting this historic Fabergé milestone event.

The story of this previously unidentified golden egg up until 1952 has now been pieced together by Kieran McCarthy of Wartski. His detective work was prompted by the opening up of the Russian archives in the 1990s, where a Fabergé invoice addressed to the Tsar for “Nécessaire Egg, Louis XV style, 1900 roubles, St. Petersburg 4th May 1889″ was discovered in the Imperial ledgers. Two years later, an inventory of items in the Gatchina Palace recorded: “Egg decorated with stones, containing ladies toilet articles, 13 pieces.” In 1917, items confiscated by the provisional government included a “gold nécessaire egg, decorated with precious stones”, and, in 1922, “1 gold Nécessaire egg with diamonds, rubies, emeralds and 1 sapphire” was among the goods transferred to the Sovnarkom, the central agency in Moscow from where confiscated items were dispersed and sold off by the state.

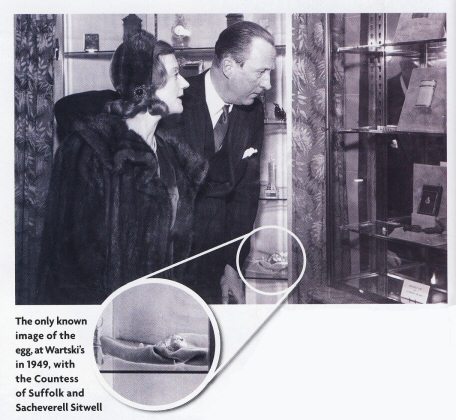

Mr. McCarthy has been able to match these descriptions of the Nécessaire Egg with that of an object included by Wartski in the first ever exhibition in the West of works solely by Fabergé. Here, in 1949, many of the splendours of the Russian court were displayed – “relics of a dead civilization and a vanished Empire”, as Sacheverell Sitwell wrote in the catalogue. At the time, the identity and Imperial provenance of the egg were unknown, and there’s no indication of who owned it. Four other Imperial Easter eggs were the stars of the show.

Searching through Wartski’s ledgers, Mr. McCarthy found an entry confirming that an object matching the description of the Nécessaire Egg was sold in 1952. The buyer was almost certainly British, and insisted on anonymity. Wartski observed absolute discretion and never recorded the name, and there is no record of it having being seen by anyone in the art world since.

But last year, Mr. McCarthy discovered the photographs taken at the 1949 exhibition. “When I saw the object on the bottom shelf of the cabinet, I knew in an instant that it had to be it. The detective work was an intellectual exercise, but the effect was physical spine-tingling rush of adrenalin, all concentrated on that square centimetre of print.” The grainy images, which have been scanned and magnified, are the only known visual record of the missing Nécessaire Egg.

The Rothschild Fabergé Clock

(Courtesy Christie’s)

“A salesroom overflowing with hundreds of onlookers fell silent as the auctioneer announced that Lot 55 was next. The bidding lasted for more than five minutes as six determined collectors fought to acquire it (The Rothschild Fabergé Egg*) … The previous record for a Russian object was established by the Fabergé Winter Egg sold at Christie’s in New York in 2002 for £6.62 million ($9.6 million) … Most of the sale proceeds will go to a charitable foundation that primarily supports classical musical causes.” (The Times [London], November 29, 2007, 42) The successful bidder was Alexander Ivanov, active in the auction market since 1994. (Moscow Times, November 19, 1994)

My £9m Fabergé Egg Was a Bargain

“Russian businessman Alexander Ivanov, who helped found Russia’s first private museum (in 1993), has a passion for Tsarist treasures … Mr. Ivanov, who bid in person at Christie’s in London, said it would be exhibited in his museum (The Russian National Museum). He added: ‘This egg was acquired cheaply – the price is nothing compared to its superior quality.’ ”

(Daily Mail [London], November 30, 2007, 30)

*Fabergé scholars are not in agreement that this object should be called an egg – they suggest it is a clock made in the shape of an egg. Made in 1902 by Fabergé, but not presented at Easter to the recipient, it was a present from Béatrice Ephrussi, the wife of a banker from Odessa, Russia, to Germaine Halphen, on the occasion of the latter’s engagement to Béatrice’s younger brother, Baron Edouard de Rothschild. He was a member of the French branch of the Jewish Rothschild banking family. A photograph of the clock has been found in Rheims, Maurice, L’Objet 1900, 1964, #29.

Fabergé Enthusiasts from Italy, the Netherlands,

UK & USA in London

(Courtesy Enzo Ascione)

Von Dervis Exhibition, 1902

(The Fabergé Menagerie, 2003, 22)

Anna and Vincent Palmade share their research journey in their own words:

The two eggs were discovered in a photograph of the vitrine of Fabergé objects belonging to Maria Fedorovna at the 1902 St. Petersburg von Dervis Exhibition.

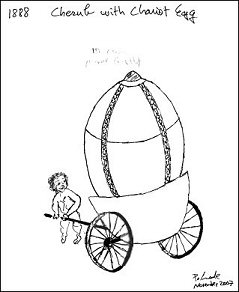

The 1888 Cherub Egg with Chariot is behind the Caucasus egg on the far right of the bottom shelf. It is almost completely hidden by the Caucasus egg, which is why it has remained undetected for more than 100 years. The egg gradually reveals itself following long and patient scrutiny with a magnifying glass. One wheel of the Chariot appears just left of the Caucasus stand, the tip of the egg is just left of the tip of the Caucasus egg and the outline of the Cherub pulling the Chariot with his two hands can be seen just above and on the left of the wheel. There are also two reflections of the egg in the vitrine glasses – the outline of the chariot can be seen on the reflection in the vitrine to the right of the egg. There can be little doubt that this is indeed the Cherub Egg with Chariot because its appearance is quite unique and matches perfectly the description in the account books of N. Petrov, assistant manager to the Cabinet of His Imperial Majesty – Cherub pulling a chariot containing an egg. (Fabergé, Proler and Skurlov, 100; Lowes and McCanless, 24-5)

The 1889 Nécessaire egg is on the far left of the second shelf from the top. Although the egg is much easier to see than the Cherub Egg with Chariot, its identification is much less straightforward; we had to go through a process of elimination using the information in Fabergé, Proler and Skurlov, 101; Lowes and McCanless, 25-7.

- The appearance of this egg does not correspond to any of the known Fabergé Imperial eggs; thus it has to be one of the five Fabergé Imperial eggs belonging to Maria Fedorovna, dating from before 1902 and for which there are no known photographic or design records (excluding of course the Cherub Egg with Chariot discussed above).

- It could not be the 1902 Empire Nephrite egg because the 1902 von Dervis Exhibition happened between the 8 and 15th of March 1902 (Old Russian calendar), i.e., one month before Easter celebrations during which the 1902 egg would have been offered.

- It could not be the 1897 Mauve Enamel egg because it is too small to contain the known surprise. In effect, a comparison with other known objects in the vitrine shows that this egg is less than 7 cm long while the surprise of the 1897 Mauve Enamel egg is 8.2 cm long.

- The shape does not correspond to the known descriptions of the 1886 Hen with Sapphire Pendant egg – Hen picking a sapphire egg out of a basket. (Fabergé, Proler and Skurlov, 95-7; Lowes and McCanless, 21-2)

- The style of the egg does not match the description of the 1896 Alexander III egg of blue enamel while the top two thirds of this egg is clearly made of golden stripes, which were quite common in Fabergé objects of the late 1880s. Gold is also the material mentioned for this egg in the 1917 Russian government list (Inventory of Confiscated Imperial Treasure) and 1922 Soviet government list (Transfer Documents of Confiscated Valuables from the Anichkov Palace to the Sovnarkom).

- The egg could also have been offered to Empress Maria Fedorovna by someone other than Tsar Alexander III or Tsar Nikolai II, but this is unlikely given that all the other eggs in the vitrine are gifts from them, and similarly, all the eggs in the adjacent vitrine belonging to Empress Alexandra Fedorovna are gifts from her husband Tsar Nikolai II.

Thus, this egg is most likely the 1889 Nécessaire egg. Other known descriptions of this egg mention the fact that it contains 13 toiletry items – a pretty surprising feat given its small size, but one also achieved by equally small and similar French nécessaire eggs – Sotheby’s Geneva, Objets de Vitrine from the Collection of Mrs. George Keppel, May 11, 1989, lot 68; Habsburg, Géza von, Fabergé: Imperial Craftsman and His World. Booth-Clibborn, 2000, 40/4.

Drawings © Palmade

Offered by Mrs. Ethel Gunton Douglas, two Fabergé Imperial silver Easter bibelots, the first a tiny amour pushing a wheelbarrow laden with an egg, 2 in. long, and a hare drawing a hinged egg on wheels, parcel-gilded. The catalogue says both items were understood to have belonged to the children of Tsar Nicholas II. Final bid $22.50.

In conclusion, we list below some of our questions which we hope will stimulate further research, and may possibly lead to the discovery of missing Fabergé eggs.

- Who was the anonymous lender of the Nécessaire egg at the 1949 Wartski exhibition?

- Who was the buyer of lot 258 at the 1941 Parke-Bernet auction? That same lot may well have also included the 1886 Hen with Sapphire Pendant egg!

- Are they pictures of these missing eggs in the family archives of Mrs. Ethel Gunton Douglas, the seller of lot 258?

- What is the object in between the wild boar and the clock in the 1902 von Dervis photograph of the vitrine containing known Maria Fedorovna’s eggs?

Resources used to make this research possible include two landmark publications on Fabergé eggs:

Fabergé, Tatiana, Proler, Lynette, and Valentin Skurlov, The Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs. Christie’s, 1997.

Lowes, Will and Christel Ludewig McCanless, Fabergé Eggs: A Retrospective Encyclopedia. Scarecrow Press, 2001.

We also would like to thank Kristen Regina, Librarian, Hillwood Estate, Museums and Garden, and Jeffrey Eger of Jeffrey Eger Auction Catalogues for giving us access to their amazing auction catalog resources.

Perkhin Workshop

(Courtesy Wartski)

The Rothschild Egg is on the work bench in the foreground, diligently tended by two bearded goldsmiths. The egg appears to have not been enamelled or mounted with its gold motifs at this stage. The enamelled cockerel surprise has been added and is visible above the egg. It was previously identified as the Kelch Chanticleer Egg of 1904. The silhouettes of the Chanticleer and Rothschild eggs are near identical, however, they do differ slightly. Immediately above the pedestal of the Rothschild egg are two stepped floral garlands. The Chanticleer egg has only a single garland and the egg in the photograph has the stepped mounts of the Rothschild egg. In the absence of a third egg with identical garlands, the egg in the picture can only be the Rothschild Egg. This dates the photograph to circa 1902, when the workshop was headed by Perchin. He is the proprietorial-looking bearded gentleman on the left of the image; his assistant and successor Henrik Wigström stands centre wearing a dark suit.

The photograph is a remarkable visual record of Fabergé’s foremost craftsmen at work. It shows Fabergé greatest Chief Workmasters; Perchin and Wigström looking on as the Rothschild Egg is made.

The Rothschilds were prominent customers of Fabergé. The family’s patronage of the firm’s London branch rivalled that of the Royal family. For a discussion of the Rothschilds relationship with Fabergé, see: Fabergé and the Rothschilds.

Workshop Detail

1904 The Chanticleer Egg (Courtesy Tatiana Fabergé)

and the 1902 Rothschild Fabergé Egg (Courtesy Christie’s)

The Two Roosters

(Courtesy Tatiana Fabergé for the Chanticleer Egg and Christie’s for the Rothschild Egg)