Spring 2012

Dear Fabergé Enthusiasts:

As we begin the seventh year of publishing the Fabergé Research Newsletter, we are delighted to share a very special invitation with our readers and to present the Spring 2012 issue of the newsletter with new research on the Fabergé jewels in the Fersman Portfolio along with the regular columns.

Save the Date for a Fabergé Symposium

January 31 – February 1, 2013

Houston Museum of Natural Science, Houston, Texas (USA)

You are invited to participate in a Fabergé enthusiast event through a partnership with Artie and Dorothy McFerrin, owners of a recently-formed

Fabergé collection, and the museum.

The gathering will include an introduction to the more than 300-piece collection shown in its entirety for the first time, followed by a private viewing, lectures by authorities, a book signing, and a visit to the amazing displays in the Cullen Hall of Gems and Minerals. The museum also has a year-around three-story butterfly house and a brand-new dinosaur wing bigger than the size of a football field.

To assist the museum in planning for the event, please respond ASAP if you would like to attend, and suggest special interest topics for the lectures.

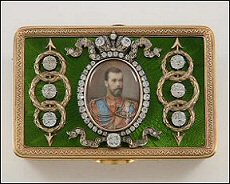

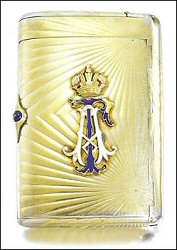

Recent Additions to the McFerrin Collection: Bismarck Box (1889), Hand Fan with a Fabergé Sticks and Guards, Lord Carrington Box (1894)

(Photographs © C&M Photographers)

Fersman Portfolio – Fabergé Jewels Reviewed

by Annemiek Wintraecken and Christel McCanless

The Four-Part Fersman Portfolio

The Four-Part Fersman Portfolio

(Courtesy Heritage Auctions)

The Fersman Portfolio is the only printed record of the Russian crown jewels based on the 1922 Inventory conducted by a Soviet-appointed commission led by Dr. Aleksander E. Fersman (1883-1945), a geochemist, mineralogist and director from 1919 to 1930 of the Russian Mineralogical Museum founded in 1716 in St. Petersburg. Today the museum bears his name. He served as the head of the Diamond Fund Commission of the USSR (1922-1926), a group of experts including Agathon Fabergé (1876-1951), second son Carl Fabergé and a gemstone specialist with his father’s firm. In 1898 Agathon was employed as an expert in the Diamond Room of the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg and as an appraiser for the Imperial Cabinet of Tsar Nicholas II, and therefore, had a familiarity with the crown and private jewels of the tsars. Four copies of the Fersman Portfolio have been on the auction market since the Fall 2010 issue of the

Fabergé Research Newsletter:

- One set in English, missing the text volume, Part I, sold for $15,535 at Heritage Auctions (October 14-15, 2010) in Beverly Hills, California.

- A complete English copy offered by Sotheby’s London (December 1, 2010) did not sell.

- A French edition realized $10,000 at Sotheby’s New York (April 12, 2011).

- An English edition sold on (November 29, 2011) for £42,050 ($65,962) including a premium, at Christie’s London (Ed. Note: Listed incorrectly on the Christie’s website as $26,912.)

The Gemological Institute of America (GIA) in Carlsbad, California, has one of the less than 20 extant English copies. Plate 12 (not Fabergé) is on view in its Tablet to Tablet: Treasured Pages from Past to Present exhibition shown in the Liddicoat Gemological Library from November 2011 – May 2012. A scanned copy of the Fersman Portfolio is available for viewing in the library.

Exhibit Case at the Tablet to Tablet Venue

Exhibit Case at the Tablet to Tablet Venue

(Photograph © Tim Adams)

Major resources consulted for this Fabergé jewels review include:

The Fersman Portfolio published in separate Russian, English, and French editions in Moscow by the People’s Commissariat of Finances (1925-26). One hundred of the jewels are illustrated and accompanied by a narrative, not always flattering, a detailed description of the stones, a commentary on the setting, and sometimes a date of the jewel’s creation.

Victor Nikitin (1949-2009), Director of the Diamond Fund of the Russian Federation (1991-1997), dreamed of tracking down all the Russian jewels sold between 1927-1936, re-photographing them and producing a lavish color catalogue of the original collection (Norman, Geraldine. “The Romance of the Stones: Moved About, Sold Off, Even Misplaced, the Russian Crown Jewels Have Had it Hard.” The Independent [London], April 6, 1997). Nikitin’s compilation was published in Iljine, Nicholas, and Natalya Semyonova, Selling Russia’s Treasures (2000, pp. 258 – 280), Appendix II: “A List of the Russian Crown Jewels”.

In November 2011 Irina Polynina, chief expert of the Diamond Fund of Russia, published a CD The Diamond Treasures of Russia, telling the story of the Diamond Fund housed in the Kremlin Armoury in Moscow.

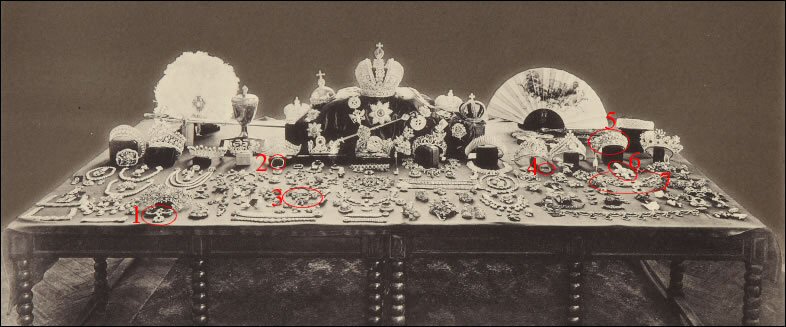

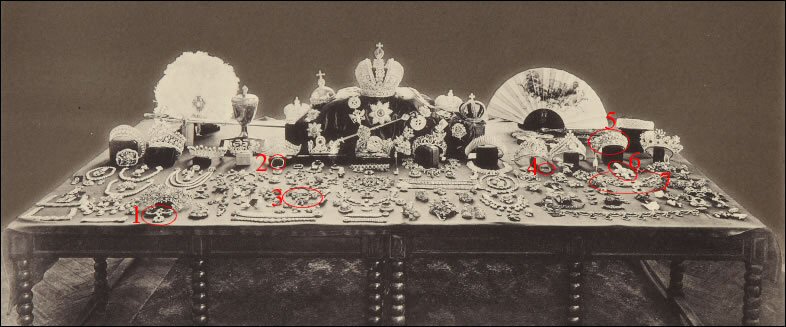

Russian Crown Jewels – Gokhran, 1922. Identified Fabergé Items in Red Circles (Fersman Portfolio, Part I, Frontispiece)

Russian Crown Jewels – Gokhran, 1922. Identified Fabergé Items in Red Circles (Fersman Portfolio, Part I, Frontispiece)

Left to Right: #1 Sévigné Brooch, #2 Emerald, #3 Plastron, #4 Ceylon Sapphire, #5 Turquoise Diadem, #6 Turquoise Brooch, #7 Slave Necklace

One of the two Ceylon Sapphires, the Rose Brooch and the Magnifying Glass could not be positively identified in this photograph.

From descriptions in the Fersman Portfolio (1925-26) based on the 1922 Inventory with references to the 1898 Inventory (both now lost), nine or possibly ten Fabergé objects may fall into the following chronological order:

ca. 1895 Turquoise Kokoshnik Diadem with Matching Brooch – Fersman No. 154 and 153 (#5 and #6)

1898 – Collier d’Esclave (Slave Necklace) and Emerald Pendant (in 2012 extant in the Diamond Fund, Kremlin) – No. 73 and 170 (#7 and #2)

ca. 1898 – Sévigné Brooch – No. 165 (#1)

1898 – Brooches (2) with Ceylon Sapphires – No. 161 (#4 and ?)

1898 – Magnifying Glass – No. 297 (not illustrated)

ca. 1900 Diamond and Emerald Set Consisting of Diadem, Necklace and Plastron (only Fabergé object in this set) – No. 139 (#3)

1922 Diamond Rose Brooch – No. 49 (#?)

Abbreviations:

* – Text from the Fersman Portfolio

** – Text from Nikitin

a.c. – Ancient carat, or 205-207 milligrams

br. – Brilliant, a smaller or special cut diamond. Small diamonds are not necessarily tiny in Fersman, they are just not the center stone or a significant size diamond in the piece. In Fersman, “diamond” has its own abbreviation: “d.”

cent. – Centimeter

Inv. – Inventory

m.c. – Metric carat, one-fifth of a gram, or 200 milligrams.

Conversion of metric carats to ancient carats.

Turquoise Kokoshnik Diadem with Matching Brooch (ca. 1895)

A stylized kokoshnik or Russian tiara is modeled after a cock’s comb (kokosh in Russian) and was originally worn in traditional Russian folk dances.

Gokhran Photograph

Gokhran Photograph

(Plate I from Fersman, Detail) Fersman Plate LXXXI: Diamond Diadem No. 154

Fersman Plate LXXXI: Diamond Diadem No. 154

with an Oriental Turquoise Diamond Brooch No. 153

Diamond Brooch No. 153

with an Oriental Turquoise

* (Fersman, No. 154) This diadem (kokoshnik), together with the brooch forms a set. Though somewhat heavily designed it still represents an artistic object surpassing by far the brooch. It was executed by Faberger [

sic] at the same time as the diadem, and it shows beautiful stones of a delicate pale blue framed by diamond stripes which are set in heavy gold. Dimensions: length (inward line) – 41 cent.; height in the centre – 62 cent. Turquoise: excellent gems beautifully matched in the form of 54 cabochons. Diamonds: good Brazilian stones described in the early Inventory [1898] as follows (in ancient carats): [Dimensions of the diamonds are not included in this review.] Setting in solid gold and silver. Each of the parts can be separated as they are fastened on different pins. The pale blue stones are set in gold, the diamonds – in silver with little golden galleries and leaves. Inv. 1898 – No. 369/361 Inv. 1922 – No. 263/a.

** (Nikitin) Part of a parure [matching set of jewelry] with a beautiful oriental turquoise and small gold leaves. All parts of the solid gold mounting can be dismantled. Made by the firm of Fabergé c. 1895. (Nikitin, p. 260) (Ed. Note: Plate number reference to Fersman is incorrect.)

* (Fersman, No. 153) This brooch forms a complete ornament set with the turquoise kokoshnik. The large, somewhat heavy stones of the brooch, do not harmonize with the dry, sharp lines of the composition which is rather poorly designed. Dimensions: 12.4 x 9.4 cent. The turquoise which decorates this jewel is very large though not without small defects. Diamonds – good Brazilian specimens described in detail in the Inventory of 1898 (in anc. carats): [Dimensions of the diamonds are not included in this review.] Setting – coarse and very massive, wrought [sic] by the firm K. Faberger [sic] about 1895. Inv. 1898 – No. 370/368 Inv. 1922 – No. 263/B.

** This brooch forms a parure with a kokoshnik. Seven flat turquoise cabochons, very large with a number of defects at the edges. The diamonds are of good quality from Brazil. The mounting is by the firm of Fabergé from about 1895. (Nikitin, p. 270)

How and when this parure became part of the crown jewels before the 1898 inventory remains a mystery, and the present whereabouts is unknown.

Costume Ball Jewels – Collier d’Esclave and Emerald Pendant (1898 & 1922)

Costume balls, an entertainment venue for the aristocracy in Russia and other European royal courts, were the highlight of any social season. By tradition, Russian Imperial jewels were reset in new designs and used on subsequent occasions, such as costume balls. From details in the 1898 and the 1922 crown jewels inventories three Fabergé jewels are connected to costume balls – a collier d’esclave, an emerald pendant and a Sévigné brooch.

Left: Marie Feodorovna, 1883 Costume Ball – Right: Alexandra Feodorovna, 1903 Costume Ball

(Courtesy StateHistory.ru) No photographs of the 1898 Costume Ball are known to the reviewers.

For the famous 1903 costume ball in the St. Petersburg Winter Palace Empress Alexandra wore a Fabergé necklace and the emerald pendant probably mounted by Fabergé. In her memoirs Grand Duchess Olga, sister of Tsar Nicholas II, describes the attire of the Imperial couple for the 1903 ball:

All of us appeared in seventeenth-century court dress. Nicky wore the dress of Alexis, the second Romanov Tsar, all raspberry, gold and silver, and some of the things were brought specially from the Kremlin. Alicky was just stunning. She was Maria Miloslavskaya, Alexis’s first wife. She wore a sarafan of gold brocade trimmed with emeralds and silver thread, and her earrings were so heavy that she could not bend her head. (Vorres, Ian, The Last Grand Duchess, 1964, p. 94)

A collier d’esclave (French for slave) or slave necklace is composed of chains, strings of beads, or jewels. Historically the gift of a slave necklace was a marital tradition in most of France’s more fortunate regions. It symbolized the transmission of wealth and the bride’s commitment made on the wedding day to produce a bounty of children. Each additional plaque of gold and its chains then corresponded to a subsequent birth. (see also Polynina, 2011, p. 134-5)

Empress Alexandra with

Empress Alexandra with

the Collier d’Esclave, and

Emerald Pendant, 1903 Fersman Plate XLIII: Necklace Called D’esclave;

Fersman Plate XLIII: Necklace Called D’esclave;

Diamonds, Pearls and Emeralds No. 73

* (Fersman, No. 73) This rich and prettily composed ornament consisting of old stones of the Cabinet, was rather hastily executed by the lapidary Faberger [

sic], for a Russian costume court-ball in 1897 or 1898. Design, composition and choice of stones are very successful, though the work is somewhat neglectful: the stones are joined together with very flexible silver wire, in order to fasten the whole

parure on the dress. Another rich jewel, a brooch

en pendentif called

Sévigné completes this elegant suit. Emeralds: very good old stones, nearly all of Russian origin. 39 stones in golden chatons: 18 square ones … [Dimensions of the emeralds are not included in this review.] In all, 39 emeralds with a total weight of 344½ m.c. (in the early [1898] inventory – 243 a.c.). Diamonds: Brazilian specimens of average value – 225 m.c. Pearls: 125 pearls of average quality – 225 m.c. and small pearls. Settings: emeralds in gold, diamonds in silver. In the Inventory of 1898 (No. 368/360) this piece of jewellery is noted as the private property of the last empress and said to be ‘unfinished’. This fact apparently explains the divergency of the old items and of the new definitions. Complimental [

sic] numbers – 130, 153 – 159, 256 – 259. Inv. 1922 – No. 412.

** Assembled in 1897-1898 by the firm of Fabergé from beautiful old stones for a court ball in Russian costumes. The incomplete esclavage was sewn on to the dress. A Sévigné brooch was made to go with it. Listed in the inventory of 1898 as belonging to the Empress Alexandra Feodorovna. (Nikitin, p. 264)

A. Kenneth Snowman (The Art of Carl Fabergé, 1953, black and white illustration No. 48) under the identical photograph from the Fersman Portfolio describes the collier d’esclave:

Made hurriedly for the Tsarina in 1898 for the famous ‘Bal de Costumes Russes’ at the Winter Palace, this sumptuous necklace in emeralds, diamonds and pearls was made up of some of the finest gems in the Imperial reserve, and was a tremendous success. The emeralds from the Urals are set in gold, and the diamonds (Brazilian) in silver. The overall length is 11 3/8 inches.

The photograph caption incorrectly identifies the necklace as part of the Russian Imperial Treasure in the Kremlin. Nikitin suggests it was sold between 1927-1936. Its current whereabouts is unknown.

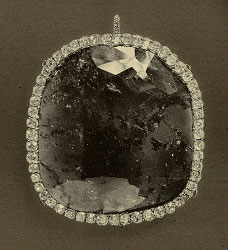

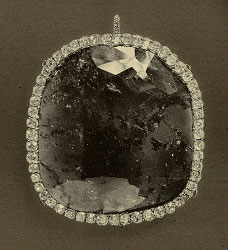

Gokhran Photograph

Gokhran Photograph

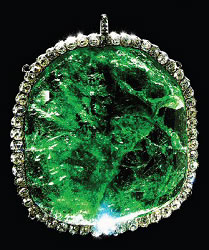

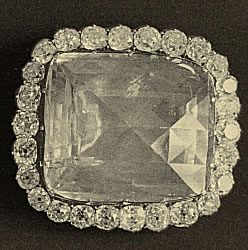

(Detail) Fersman Plate LXXXVII: Pendant

Fersman Plate LXXXVII: Pendant

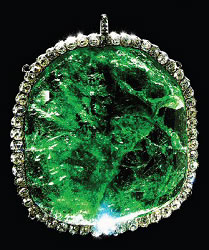

with Large Emerald No. 170 Emerald Pendant, 245 Carats

Emerald Pendant, 245 Carats

(Courtesy Diamond Fund, Kremlin)

* (Fersman, No. 170) This excellent stone of a lovely green, in spite of numerous cracks, weighs about 240-250 m.c. The surface of the gem is convex, like that of a flat cabochon, around which is a wide row of facets. On the reverse side, polished cavities can be seen. The whole form of the stone is irregular. The emerald is set in gold and bordered by 54 diamonds (about 12 m.c.) in silver settings, soldered in gold. The work of the jewel refers to the time of Nicolas I. The emerald’s particularly yellow-greenish tone, proves it to be of Russian origin. It evidently is one of the first gems found in the emerald mines of the Ural, about 1835. Dimensions: 6.8 x 6.3 x 1 cent. (Ed. Note: In the 1980’s the origin of the emerald as being from Columbia in South America was confirmed, Polynina, p. 193.)

Polynina (2011, p. 193-4) presents a very convincing case that this emerald pendant – the companion piece to the slave necklace worn by the Empress in 1903 – is probably the only Fabergé-related object retained in the Diamond Fund from the original Russian crown jewels:

The attire, resembling the dress of Tsarina Maria Iliinichna Miloslavskaya, the first wife of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich, was made for the Empress Alexandra Feodorovna. A month before the ball, the Empress and her sister Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna spent over two hours in the Diamond room selecting the emeralds, diamonds, pearls and jewels for their costumes. They were accompanied by a court jeweller Agathon Fabergé and a director of the Hermitage, I. Vsevolzhsky, who looked after historical accuracy of the costumes.

The photograph of the Empress in the masquerade dress show us the jewel, kept today in the Diamond Fund, the flat deep-green emerald is easy to recognize. Probably, for this very occasion Agathon Fabergé made a mount for the emerald of 54 large round diamonds and added an eyelet for the fastening, thus converting a stone into a pendant. There are memoirs of the guests of the ball, who were astonished by the ‘palm’ size and the colour of the giant.

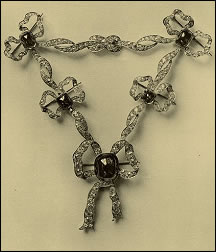

Sévigné Brooch (ca. 1898)

Gokhran Photograph

Gokhran Photograph

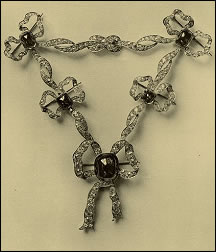

(Detail) Fersman Plate LXXXVII:

Fersman Plate LXXXVII:

Emerald Sévigné Brooch No. 165

A Sévigné brooch is a bow-shaped jewel named after the Marquise de Sévigné (1626-1696), a French writer.

* (Fersman, No. 165) A rich and beautiful brooch, belonging to the same set, as the unfinished necklace No. 142 (old inventory) both jewels being ordered for a fancy-dress ball about 1898. The brooch was made in great haste by the firm of Faberger [

sic], out of old stones belonging to the reserve of the Cabinet, tied together with pearls

(Ed. Note: No pearls are shown in the Fersman Portfolio photograph) by a thin silver thread. A piece, very successfully composed and designed. Emeralds: excellent old Columbians [sic] of a curious old cutting, with a slightly rounded surface. The old lists [1898] mention 2 emeralds of rhomboidal form – 140 a.c. which when reweighed, proved to be 174,10 m.c. Another hexagonal stone in a pendant was found to weigh 21,90 m.c. instead of 21 a.c. Diamonds: Brazilian specimens of a yellowish tint and varied in quality. According to the old Inventory [1898], 15 solitaires (No. 44) – 32 a.c.; 3 solitaires (No. 45) – 5½ a.c.; 48 diamonds (No. 124) – 38 a.c.; 24 br. (No. 130) – 4 a.c. The recent valuation of our experts proves a far greater quantity of diamonds, with a total weight of 100 m.c. Workmanship – about 1898, somewhat heavy, but still of great effect and in perfect harmony with the old Russian style.

** This rich and beautiful brooch belongs to the same parure as the unfinished necklace. Made in about 1898 for a costume party by the firm of Fabergé from old stones in the Imperial Cabinet. (Nikitin, p. 270)

The reviewers puzzled by the mention of pearls in the Fersman text asked Irina Polynina, chief expert of the Diamond Fund, for a clarification. She writes:

In 1898, one of the historical costume balls was being prepared. As a rule for balls of this type for members of the tsar’s family, temporary jewelry was made from separate stones and old decorations from the Cabinet. Often, these jewels were sewn on the fabric of dresses, sometimes decorations were made from separate fragments, braids, strings and afterwards, all these pieces were unfastened, untied, and were returned to the Cabinet. And for the next occasion, these elements from the previous decoration could be used again. I suggest the brooch could have been tied to pearls with silver thread and later on the brooch and pearls were separated. Fersman’s description of the brooch is not very clear. One may interpret the Russian words “in haste” translated into English also as “hurriedly”, meaning the brooch was affixed quickly to the pearls. You see in the detailed description of the stones Fersman gives the full list of diamonds and emeralds, and he does not mention any pearls. In my opinion, it is not the brooch which was made hastily, but rather it was assembled quickly to the pearls with a silver thread.

Since the reviewers have not been able to identify this brooch on an existing court ball photograph, it is not clear why this brooch is said to belong to the same parure as the unfinished necklace.

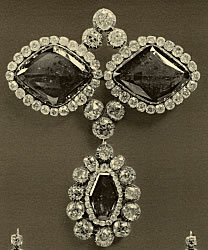

Sapphire Brooches (1898 & 1922)

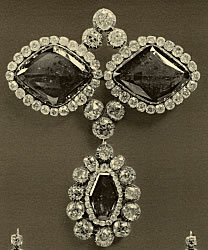

Fersman Plate LXXXVI: Two Brooches with Ceylon Sapphires

I. Brooch with 26 Diamonds II. Brooch with 24 Diamonds No. 161

* (Fersman, No. 161) Two beautiful brooches-

fermoirs decorated with ancient sapphires from Ceylon.

(Ed. Note: A fermoir is a buckle for a necklace or a decorated clasp.)

-

A very large sapphire of 249,25 m.c. encircled by 26 brilliants of average quality (20 m.c. appr.). Dimensions of the brooch – 5.11 x 4.4; of the stone – 3.8 x 3.3 cent.

-

A large sapphire of a rather flat Hindu cutting, weighing 142 m.c. and 24 white diamonds of 16 m.c. (appr.) set in silver. Dimensions of the brooch – 4.7 x 4.3; of the stone – 3.4 x 3.1 cent. Setting is modern, by Faberger [sic]. Inv. 1898 – No. 109/106 and No. 108/106. Inv. 1922 – No. 491/393 and No. 492/108.

** Two clasp brooches with old Ceylonese sapphires with old-style Indian facetting set on foil in a mounting by the firm of Fabergé. (Nikitin, p. 271, only illustrates Brooch No. I)

Papi and Rhodes (Famous Jewelry Collectors, 1999, 171-2) cite from the Fersman text the sapphire brooch with the large Hindu cutting with 24 diamonds (II. above), but their illustration shows the brooch with 26 diamonds (I. above). They state correctly the brooch was not sold at the 1927 Christie’s London auction. (Ed. Note: Neither brooch was in the auction). Papi and Rhodes state: ‘… exactly how it was acquired by Cartier is unknown but in their archives it is referred to as the sapphire historique from the Russian Tsars’, and they conclude the sapphire historique from the Russian crown jewels appeared in various necklaces worn by the wealthy opera singer Ganna Walska (1887-1893). The authors of this review are not convinced the Walska jewels illustrated by Papi and Rhodes match either of the Fersman sapphire brooches mounted by Fabergé. Walska was the one-time wife of International Harvester millionaire Harold McCormick, and the owner of the Fabergé Duchess of Marlborough Egg from 1926-1965.

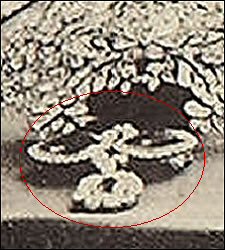

Large Magnifying Glass (1898 & 1922)

* (Fersman, No. 297, not illustrated in the

Fersman Portfolio) This is a large magnifying glass, with a golden rim, covered with white enamel and green leaves; the handle is of nephrite from Sayanne. The initials N. II. indicate that it belonged to the tsar Nicolas II. The object is the work of the jeweller Petrov, who was engaged for this task by Faberger [

sic]; this is confirmed by the inscriptions on the setting: Faberger [

sic] and M.P. Dimensions: diameter of the glass with the rim – 8.3 cent. Length, with the handle – 20 cent. An interesting piece for a museum. Inv. 1898 – No. 141. Inv. 1922 – No. 141.

(Ed. Note: Object retained the same number from the 1898 inventory.)

** A large magnifying glass with a gold rim covered in white enamel with green leaves and a handle of Sayan nephrite. Inscribed with the initials “N.P.A.”, indicating that the glass belonged to Nicholas II. Made by the jeweller Petrov for the shops of the firm of Fabergé. (Nikitin, p. 279)

Nephrite from Sayanne suggests the mineral was mined in the Sayan Mountains near Lake Baikal in Siberia. Aleksander F. Petrov was regarded as Fabergé’s chief enameller and was employed by the firm from 1894-1904. In the opinion of the reviewers, the Fersman text –

inscriptions on the setting: Faberger [

sic] and

M.P. – is perhaps the work of Mikhail Perkhin (1860-1903), Fabergé’s head workmaster beginning in 1886 until his death.

The initials “N.P.A” (Nikitin, p. 279) – differ from the Fersman Russian text “H.II A.” when the magnifying glass was last examined. The monogram for the Tsar was usually depicted in this fashion:

Plastron (1922 & 1985 reproduction)

Gokhran Photograph

Gokhran Photograph

(Detail) Fersman Plate LXX: Plastron (by Fabergé)

Fersman Plate LXX: Plastron (by Fabergé)

No. 139 A Plastron 1985 Reproduction

Plastron 1985 Reproduction

(Diamond Fund, Kremlin)

A plastron is a bodice decoration, also known as a stomacher or devant de corsage. In this parure it is the only object made by Fabergé in the Moscow branch and is the only one reviewed here.

* (Fersman, No. 139. The Portfolio has separate designations for the three objects – A: Plastron, B: Necklace, C: Diadem) Diamond set with large emeralds. A magnificent set with large emerald cabochons, consisting of a diadem, a necklace and a plastron. The diadem and necklace (Ed. Note: Not discussed in this review, are illustrated in Munn, Tiaras: A History of Splendour, 2001, p. 407) ordered by [sic] the empress Alexandra Feodorovna, were made in great haste by Bolin, St. Petersburg, the plastron by the Moscovian section of the firm Faberger [sic]. The latter piece evidently was ordered by the Grand Duchess Elisabeth Feodorovna. The whole piece is in à-jour silver, with golden galleries. All the separate parts can be taken off, for which purpose they are numbered. The stones were furnished by the two firms, South-African specimens only being used. The whole set is remarkably pretty, although neither the idea nor workmanship are original. Inv. 1922 – No. 289/a.

The reviewers wonder if the diadem and necklace were ordered for instead of by Alexandra Feodorovna. The fact that the work was done “in great haste” is here perhaps explained by the sudden marriage of the Imperial pair in 1894, followed by the coronation, both unscheduled events due to the death of Tsar Alexander III. And why was the plastron made in Moscow? Grand Duchess Elisabeth Feodorovna, sister of Alexandra Feodorovna, had been living in Moscow since 1891 when her husband, Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich, was appointed Governor of Moscow. Was it possibly a personal gift?

* (Fersman, 139 A) A very large triangular

plastron, composed of three intertwined branches with five bows. Each individual part is very pretty, although on the whole it is somewhat poor and dry in composition. Four pins belong to the

plastron. Dimensions: width – 18 cent., height – 17 cent. Emeralds: 5 rectangular cabochons, the largest of these weighs – 45 m.c., the rest about 50 m.c. Diamonds: good African stones and roses; 228 specimens with a total weight of about 85 m.c. Workmanship of the Moscovian section of the firm Faberger [

sic] about 1900, and accomplished by the jeweller Os

car Piel [

sic] whose initials – O. P. – are engraved on the golden stamps.

(Ed. Note: Oscar Pihl died in 1897.)

** A large triangular plastron from a set which was apparently commissioned by Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna (Ed. Note: sister of the Empress Alexandra) and made in the Moscow branch of the firm of Fabergé by the craftsman Oskar Pil [sic] as indicated by the letters “O.P.” stamped into the gold. (Ed. Note: Oskar Pihl was a designer and did not have a mark of his own.) The diadem and necklace for the set were ordered by [sic] Alexandra Feodorovna from Bolin because the work was urgent. (Nikitin, p. 270)

Over the years some confusion has existed concerning Os

kar Pihl, the designer, and Os

car Pihl, the head of a workshop. The latter, Os

car Pihl (1860-1897), one of 11 children born in Finland, was adopted by his uncle, a clock maker in St. Petersburg. He headed the Moscow jewelry workshop for Fabergé from 1887 till his early death. The shop had 38 workmasters and 11 machine-tools producing mainly small jewelry items. The workshop description coincides with the

plastron, since it is a smaller jewelry item than the diadem and the elaborate necklace. The Fersman Portfolio does not mention this suite in the 1898 inventory, probably indicating it entered the Diamond Fund after 1898.

The plastron was probably sold by the Bolsheviks and its whereabouts is unknown. In 1985 a copy was made by contemporary Russian craftsmen based on a design by V.V. Nikolaev for the Diamond Fund. Slightly altered from the original by Fabergé, cabochons were used instead of the emerald-cut stones to better match the Bolin pieces.

Fabergé often improvised on a successful theme or design for other clients. Even though not identical, a favorite piece of jewelry worn as a necklace and a headband with a detachable diamond and also as a brooch is seen in publicity shots of the prima ballerina Mathilda Kschessinska, a recipient of Fabergé jewelry and friend of the Tsesarevich, later Tsar Nicholas II.

The charm of the plastron is best expressed by Irina Polynina – ‘the shaping of a softly tied-up bow has always been considered the top of the jeweler’s mastery.’

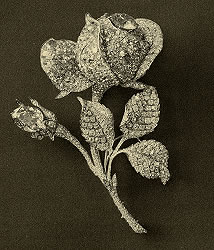

Diamond Rose Brooches (1820-30, 1922 & 1970 Reproduction)

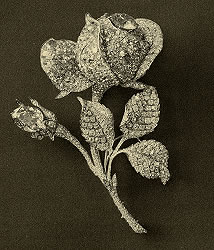

Fersman Plate XVI: Diamond Rose

Fersman Plate XVI: Diamond Rose

Brooch, 1820-30 No. 21 Fersman Plate XXXIII: (Fabergé) Diamond

Fersman Plate XXXIII: (Fabergé) Diamond

Brooch Representing a Rose with Leaves

No. 49 Rose Brooch 1970 Reproduction

Rose Brooch 1970 Reproduction

(Diamond Fund, Kremlin)

* (Fersman, No. 49) This brooch successfully reproduces an ancient model, and shows a great improvement in the jeweller’s art of our century. The jewel is executed by the firm Faberger [

sic], and proves great taste and ability. The flowers are made of beautiful yellow diamonds, and pretty white ones sprinkle the leaves. Dimensions: 11.5 x 7.5 cent. Brilliants: about 500 diamonds, and roses of a total weight of 80 m.c. In the rose, is a light-yellow diamond of good water, in the bud – one of a darker shade. Weight of both – 22 m.c. (app.) Total weight of the diamonds – 100 m.c. Setting: pale gold à-jour. Inv. 1922 – No. 292.

** A beautiful formal dress ornament made in the early 20th century by the firm of Fabergé in imitation of an old original of the early 19th century. The setting is gold openwork. (Nikitin, p. 272)

Snowman (The Art of Carl Fabergé, 1953, black and white illustration No. 47) describes the diamond rose brooch:

A replica by Fabergé of an antique, beautifully set with white stones for the leaves and carefully graded champagne diamonds for the flower, mounted in pale gold. The total weight of the diamonds is no less than 100 carats, and the height is 4 ½ inches. (Ed. note: The 1953 photograph caption incorrectly identifies the brooch as part of the Russian Imperial Treasure in the Kremlin.)

Nikitin suggests it was sold between 1927-1936. Its current whereabouts is not known. Polynina (2011, p. 198, 201-2) explains the existence of a similar diamond rose brooch in the Diamond Fund. In 1967, a decision was made to exhibit the Russian crown jewels and to display the works of contemporary Russian jewelers along with past masterpieces. Three years later the Experimental Laboratory of the Gokhran was organized and existed until 2000. Based on sketches by V.V. Nikolaev and consisting of 1466 diamonds set in platinum, a life-size white rose, in which ‘every single stone has a full faceting … rare for diamonds of this size’, was created in 1970.

The research of those who have gone before us in fascination of this topic has been invaluable. So what do we think happened to the objects in those turbulent times? Were the Fabergé objects destroyed or dismantled for the value of the gems they contained? Were they sold to Norman Weisz, a Hungarian-born jewelry merchant trading in London, or later buyers? Did Agathon Fabergé and other experts receive objects in lieu of pay for their services?

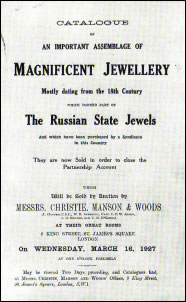

Only time will tell, if in “hidden treasures” yet to be found, other Fabergé jewels from the Fersman Portfolio have survived. Today the Diamond Fund, the Russian crown treasury instituted by Peter the Great in 1712, and also located in the Kremlin Armoury, probably contains one Fabergé object – an emerald pendant – listed in the Fersman Portfolio and saved from the confiscated treasures. We do know the Fabergé jewels reviewed in this essay were not sold at the London auction in 1927.

Catalogue of an Important Assemblage of

Catalogue of an Important Assemblage of

Magnificent Jewellery – Mostly Dating

from the 18th Century which Formed

Part of The Russian State Jewels

(Courtesy Marie Betteley)

Our thanks to the Hillwood Estate, Museum & Gardens Library staff and especially, library volunteer Leonie Ritscher in Washington (DC), Dr. Eric Smylie of Heritage Auction Galleries in Dallas (Texas), and Karen Kettering of Sotheby’s (New York), all of whom supported our research with photographic and textual images, and to our research friends – Irina Polynina, whose CD on this subject and her email discussions were immensely helpful, Rose Tozer, senior librarian, Liddicoat Library of the Gemological Institute of America, and independent researcher Joanna Wrangham, all of them worked diligently with us in preparing this review.

Auctions

May 22-23, 2012 Jackson’s International Auctioneers, Cedar Falls, Iowa

Important Asian, Russian, European & American Works

May 28, 2012 Christie’s London

Russian Art

May 30, 2012 Sotheby’s London

Russian Works of Art, Fabergé and Icons

May 30, 2012 Bonhams London

The Russian Sale

May 30-31, 2012 Bukowskis Helsinki

The Spring Classic Sale

June, 2, 2012 Auction House of the Russian Federation, Moscow

Fine Art and Antiques Auction

June 18, 2012 Coutau-Bégarie, Paris

Art Russe, Fabergé

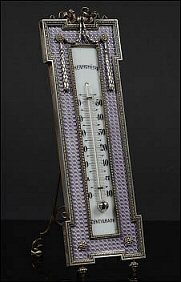

Guilloché Enamelled Thermometer

(Courtesy Coutau-Bégarie)

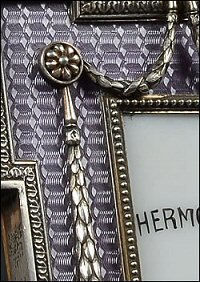

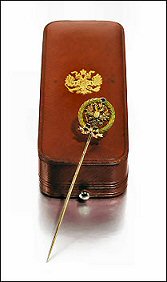

Thieleman Pin

Thieleman Pin

(Courtesy Sotheby’s London)

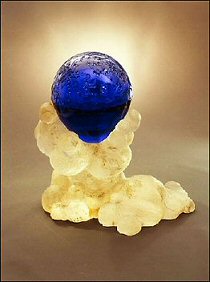

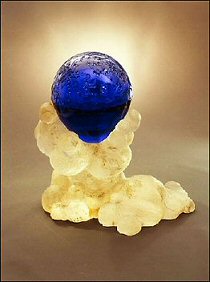

March 24 – May 20, 2012 Art Museum Riga Bourse, Riga, Latvia

Fabergé

Includes the 1917 Tsarevich Blue Constellation Egg.

May 4, 2012 – January 19, 2013 Taubman Museum of Art, Roanoke, Virginia

Fabergé from the Hodges Family Collection

Over 100 Fabergé pieces from the Hodges Family Collection assembled by American collector Daniel L. Hodges are on view.

June 23, 2012 – January 6, 2013 Bowers Museum, Santa Ana, California

Fabergé: Imperial Jeweler to the Tsars

Over 120 objects from the recently formed Artie and Dorothy McFerrin Collection and now the most important private collection of Fabergé will be shown. Highlights with fascinating historical provenances include the Empress Josephine Tiara, the Nobel Ice Egg, the Fire Screen Picture Frame, a 1902 Nicholas Presentation Box, and the Wedding Clock bought by Tsar Nicholas II and his wife, Alexandra Feodorovna, shortly after their marriage.

October 14, 2012 – January 21, 2013 Detroit Institute of Arts, Michigan

Fabergé: The Rise and Fall, the Collection of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (New Title)

Over 200 objects on loan from the Pratt Collection housed at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts will include the 1912 Tsarevich Egg and three additional Imperial Fabergé eggs. Ancillary activities will allow museum visitors to imagine the ways in which these items were made in the Fabergé workshops, displayed in a storefront, and how they adorned the interior of the imperial palaces and homes of the aristocracy in Russia and other royal courts in Europe.

1912 Tsarevich Egg

1912 Tsarevich Egg

(Courtesy Virginia Museum of Fine Arts) Unfinished 1917 Blue Tsarevich

Unfinished 1917 Blue Tsarevich

Constellation Egg

(Courtesy Art Museum Riga Bourse)

February 1, 2013 Houston Museum of Natural Science, Texas

Opening of a permanent Fabergé exhibition. In the meantime a rotating collection will be on display from the McFerrin Collection in the Cullen Hall of Gems and Minerals of the museum.

General News

Naryshkin House Treasure found in St. Petersburg old – over

1,000 pieces of antique silverware, medals and jewelry, many of them wrapped in newspapers dated August-September 1917 (just before the Bolshevik Revolution) have been found during a restoration project in St. Petersburg, Russia. Workers found the treasure in a mansion at No. 29 Ultisa Tchaikovsky owned by the Naryshkin noble family since 1875. The contents were nationalized by the Bolsheviks. The collection will be put on temporary display at the Konstantin Palace in Strenla later this year. (Courtesy Paul Gilbert,

Royal Russia) A researcher commenting on the biggest cache of Russian silver and jewelry summarized the discovery as “very important for us who study the life-style and taste of the

fin de siècle in imperial St. Petersburg.”

October 2, 2012 The Queen’s Gallery, Palace of Holyroodhouse, Edinburgh, Scotland

Caroline de Guitaut, Royal Collection curator, and Kieran McCarthy of Wartski will explore the tastes of six generations of royal collectors, from Queen Victoria to Her Majesty The Queen and His Royal Highness The Prince of Wales. Discover the stories behind some of the finest examples of Fabergé, and enjoy exclusive access to key pieces during a private viewing of Treasures from The Queen’s Palaces.

Publications

Rupasov, Alexandr I., Skurlov, Valentin V., Fabergé, Tatiana F., and Stanislav K. Bernev,

Агафон Фаберже в красном Петрограде (Agathon Fabergé in Red Petrograd), Liki Rossii, 2012. In Russian.

The book describes important periods in the life of Agathon Fabergé (1876-1951), son of Carl Fabergé and grandfather of Tatiana Fabergé. Included are his activities during the early years in Soviet Russia, when he tried to survive in the new conditions, collaborated with the Soviets, and worked with the Fersman Commission inventorying confiscated treasures. That period was very difficult for Agathon Fabergé – he was arrested on May 31, 1919, was sent to a prison for about a year, became seriously ill, and was treated for epidemic typhus in the Diagnostic Institute of Forensic Neurology and Psychiatry. Examination records of Fabergé and his letters are published here for the first time.

After his release from prison Fabergé married Maria Alexandrovna Borsova and spent six years with her in Russia, full of troubles, while he worked as an expert in GOKHRAN (State Depository of Valuables). In 1924, he spent another six months in prison. The published correspondence with his first wife, Lidiya Alexandrovna (born Treiberg), with different persons sheds new light on this period of Agathon’s life. Connections with Finnish smugglers allowed Fabergé, his second wife, and son Oleg in December 1927 to cross the border and escape from Russia to Finland. There is a detailed well-documented description of this risky event in the book. The last chapter describes the life of Fabergé and his family in Finland where he was active as the well-known collector and expert in philately, and his contacts with connoisseurs from different countries became notable. The book will be interesting for a wide audience. (Courtesy of Galina Korneva and Tatiana Cheboksarova)

Readers, who missed the 2011 Fabergé Revealed exhibition at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond, can enjoy videos of the five eggs in the Pratt Collection, and download audio files of the most important Fabergé pieces, including the eggs and the hardstone sailor.

Readers Forum

Géza von Habsburg and Alexander von Solodkoff are looking for information about and illustrations of

hardstone carvings, in particular of animals (with their original fitted cases), by Russian retailers/workshops other than Fabergé, such as Bok, Bolin, Britsin, Denisov-Uralski, Ekatarinskaya Fabrika, Ovchinnikov, Petergovskaya Granil’naya Fabrika, Sumin, Woerffel, for a new book. (

Email)

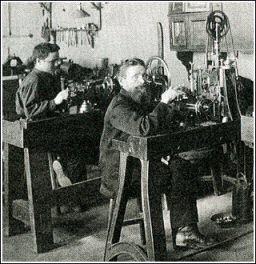

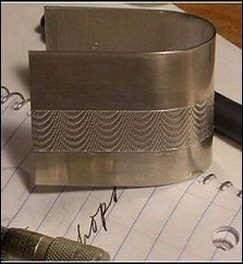

Lawrence Heyda, an admirer of the art of Fabergé, shared his knowledge and experience with guilloché machines. Guilloché is machine engraving on a metal ground (gold, silver) to which is applied a final transparent enamel layer. Two basic types of engine turning machines are the straight line and the round or rose engine. The details of each type vary according to the manufacturer, but the operation for all of them is basically the same.

Fabergé Guilloché Workshop

Fabergé Guilloché Workshop

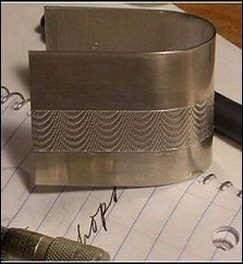

(A.N. Ivanov, Unknown Fabergé) Guilloché before Enameling

Guilloché before Enameling

(Courtesy of the Artist, Lawrence Heyda)

Fabergé’s machines were somewhat different from mine, but the same patterns can be made using a particular bar or rosette design mounted on the machine. Fabergé used mostly the straight line machines producing the sine wave pattern undulating across the surface on many of the firm’s cigarette cases. The undulations were created by gradually raising the pattern bar in small increments until the top of the wave is reached, then lowering it, repeating, etc. It is very tedious work, and if one forgets to crank the dial that moves the bar, the work is ruined. Engine turning is a very quiet and solitary operation without motors, just a hand crank, and a little dial to change the heights, but the effect can be very beautiful. The thermometer illustrated in the Auction section is guilloché enamel. See also previous discussion on this topic,

Fabergé Research Newsletter,

Winter 09-10.

Cigarette Cases by Fabergé? Newsletter readers occasionally send photographs of interesting objects with a few clues and always accompanied by many questions. As editors of this newsletter, we gather information to share with others fascinated by the original Fabergé objects prior to 1917. We do not authenticate or appraise – that is in the purview of the professional Fabergé dealers. We are enthusiasts of original Fabergé, and are not excited by the Fauxbergé regretfully so common today. Just this once, we accepted a research challenge for three cigarette cases and with generous support from our esteemed colleagues, we are sharing the results below.

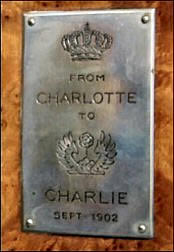

Query No. 1: A Karelian birch case with an unidentified yachting pennant on its cover and a commemorative plaque on the inside lid has no marks. The reader wants to know if it can be attributed to Fabergé? And what can be learned from the pennant on the cover and the symbols on the plaque with an inscription? Based on the dedication the reader believes the case was presented in September 1902 to Grand Duke Charles Edward (Carl Eduard), Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha by either his cousin, Princess Margaret (Charlotte) of Connaught, or his cousin, Princess Charlotte of Prussia, sister of Kaiser Wilhelm II.

Karelian Birch Cigarette Case with Plaque

(Courtesy Leo Donahew)

Suggestions for further study:

-

Smaller Russian goldsmiths sold this type of case now and then with gold or silver decorations as little souvenirs, not unlike Karelian birch frames. This hard wood growing in Sweden, Finland, and western Russia, is named after Karelia, first a part of Russia, then after World War I, a part of Finland, and after World War II, part of the Soviet Union. Its bulbous growth is caused by a genetic defect of a tree growing in a sub-arctic climate. Frequently used in combination with silver decorations for boxes, spoons, letter openers, etc., among St. Petersburg jewelers and silversmiths, this wood art tradition was a part of the late 19th century revival of the Russian style.

-

Margaret (called Daisy by her family) of Connaught – was she the future crown princess of Sweden (married Gustav Adolf in 1905)? Most likely she would not have had a Russian birch case.

-

Can the pennant be verified in connection with the yacht clubs at Cowes? The royal families (both British and German) frequented Cowes. The Russian pennants did not have blue crosses. Another colleague suggested studying the World Flag Database.

-

The crown is a royal one, but what country? The ‘eagle’ is basically a pair of wings on a torse as one would see in a crest on top of a shield in a coat of arms. Visual examples for study are (Picture 1) and (Picture 2).

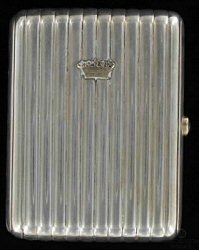

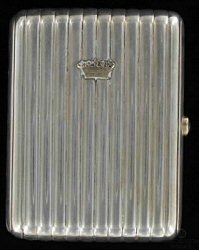

Query No. 2: A cigarette case marked as Fabergé with a scratched number (32849) and a crown on its cover was offered at the Pawn Bank of Sweden (Pantbanken Sverige) during an internet auction in 2011.

Price realized was 11,000 SEK (€1200, $1,600). The object sold for the estimate with only one bid at 20-25% of the market value. Willand Ringborg writes “it is not often antiques are sold via this channel, and the pawn shop evaluation for the client is normally the scrap price of the metal, so maybe the original owner became positively surprised – the surplus after the sale goes back to the original owner, minus costs”. Was it a true bargain for an authentic piece, or an overpriced fake?

-

The quality of the piece is mediocre. Even during the later part of World War I, when there was lack of precious metals, the Moscow shop did not lack skilled craftsmen in its remaining workforce, and the quality of the industrial production was still fine.

-

A heavy concentration of silver polish around the coronet (of a baron) is present. A coronet would not have been soldered to a case at Fabergé; it would have been applied mechanically – with small rivets. Of course, it could have been added later.

-

Scratch numbers on a piece do not confirm it is a Fabergé piece. Other jewelers used the scratch number system to trace pieces, and for inventory control.

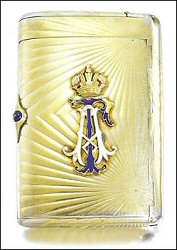

Query No. 3: Based on a story in the

Fabergé Research Newsletter,

Winter 11-12 Roy Tomlin, a reader from Virginia, discovered a

Tillander cigarette case (Sotheby’s London, June 9, 2010, Lot 692) with an identical monogram for Grand Duke George Alexandrovich (1871-1899), younger brother of Tsar Nicholas II.

Cigarette Case Marked as Fabergé

Cigarette Case Marked as Fabergé

(Courtesy Pantbanken Sverige) Alexander Tillander Cigarette Case

Alexander Tillander Cigarette Case

(Courtesy Sotheby’s London) Cigarette Case Incorrectly

Cigarette Case Incorrectly

Attributed to Alfred Thielemann

(Courtesy Sotheby Parke Bernet)

According to Dr. Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm, her great grandfather, Alexander Gustavovich Tillander (1837-1918) and his son Alexander Alexandrovich Tillander (1870-1943) had a retail shop from 1909-1911 at 28 Bolshaya Morskaia in St. Petersburg, Russia, four doors away from the Fabergé shop. Their specialties were gem-set gold jewelry, diamond jewelry, jettons, and enameled objects of various kinds. After 1911, the Tillander workshop was owned and managed by long-time collaborator and workmaster Theodor Weibel, who marked the production TW. In 1920, the Tillander workshop re-opened in Helsinki with the same lozenge-shaped cartouche.

Thielemann, a Fabergé workmaster from 1880-1910, specialized in gold, enameled and gem-set jewelry, Imperial presentation jewelry, miniature Easter eggs and jettons. His son Rudolf Thielemann continued the business after 1910.

-

A review of the biographical data for the Tillander and Thielemann workshops (Lowes and McCanless Fabergé Eggs: A Retrospective Encyclopedia, 2001, p. 239) immediately suggests Thielemann did not make cigarette cases. A Thieleman piece is illustrated in the Auction section of this Newsletter.

-

Of particular interest are the workmasters cited in the descriptive texts – Alexander Tillander

and

and  and, Alfred Thielemann

and, Alfred Thielemann  . Both are known to have signed their pieces with the initials AT.

. Both are known to have signed their pieces with the initials AT.

-

Dr. Tillander-Godenhielm confirmed her family’s jewelry business made cigarette cases “by the score for the Imperial Cabinet”. In her 2005 publication, Russian Imperial Award System, 1894-1917, pp. 387-93, she compiled a rather complete list of Imperial suppliers and the Tillander firm is included.

-

The 1973 auction catalog provenance of Fabergé and Thielemann is incorrect on two counts, the mistaken identity of the mark and the known specialties of the shop.

An important resource on cigarette cases is the in-depth study, The Fabergé Case (published in 1998) by the late John Traina. His collection of several hundred cases is now part of “The Link of Times” Collection owned by Viktor Vekselberg, a Russian collector and since 2004, the owner of 190 Fabergé objects formerly in the Forbes Magazine Collection.

Searching for Fabergé

Joanna Wrangham discovered an article in the web-published

Petersburg Age Magazine about an 1899

Fabergé casket with a dedication to Alexandra Feodrovna now in the Pavlovsk Palace Museum. It is illustrated with a photograph of the Palisander Room in the Alexander Palace showing the casket.

Fabergé Casket in Pallisander Room

(Courtesy Petersburg Age Magazine)

and

and  and, Alfred Thielemann

and, Alfred Thielemann  . Both are known to have signed their pieces with the initials AT.

. Both are known to have signed their pieces with the initials AT.