Lowes & McCanless, 2001

Tillander-Godenhielm, 2001

First Fabergé Imperial Egg and a Possible Prototype – Saxon Royal Egg, Collection

of Augustus the Strong (1670-1733)

(Courtesy Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia; Géza von Habsburg)

However, Fabergé, Proler, & Skurlov reported in Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs (London, 1997), an exchange of letters between Tsar Alexander III and his brother, the Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich, which settles the issue beyond doubt.

In a letter dated March 21 (OS), 1885, Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich advises Alexander III that:

The letter goes on to describe in detail how the egg and its various surprises should be correctly opened. Alexander III replied the same day from Gatchina Palace:

Obviously the tsarina was delighted, for a tradition had begun that would become the zenith of the decorative arts in the Western world. While these letters explain when the tradition started, the reason why is still not known. The last sentence of the tsar’s letter suggests there was a specific reason for the gift.

H. C. Bainbridge was adamant that Fabergé approached the tsar with the idea (Presentation of Imperial Russian Easter Gifts by Carl Fabergé (New York), and Hammer Galleries exhibition catalog, September 8 – November 30, 1939). Mogens Bencard in the exhibition catalog, Maria Feodorovna, Empress of Russia (Copenhagen, 1997), believes there was a meeting between Fabergé and the tsarina (and not the tsar) before the egg was made. Suggestions have been made that Armand Hammer took the Tsar Imperial First Hen Egg out of Russia. Indeed, Hammer himself claimed to have done so. However, the egg Hammer purchased was sold to Matilda Geddings Gray and is still in the Gray Foundation Collection. It is not the egg sold at the Christie’s auction in London on March 15, 1934, which is the first Tsar Imperial egg. Further detail can be found under ‘Crown Egg’ in the first two citations listed above.

A. Kenneth Snowman pointed out a similar egg exists in the Danish Royal Collection, which may well have been known to Marie, formerly the Danish Princess Dagmar. Fabergé made a number of other eggs similar to the First Hen Egg. Géza von Habsburg in “Fabergé’s Imperial Eggs – Their Inspirations and Prototypes” (Fabergé Research Newsletter, Fall 2013) discusses several prototypes for this egg.

- March 24 (OS), 1885. Would have been presented to Marie Feodorovna, a gift from Alexander III; cost 4,151 rubles, 75 kopecks. Housed in the Anichkov Palace

- September 16-20 (OS), 1917. One of forty or so eggs sent to the Armoury Palace of the Kremlin in Moscow by the Kerensky Provisional Government for safekeeping

- ca. 1920s. Bought by dealer, Derek (Editor’s note: Frederick?) Berry, London, probably from Russian officials in Berlin or Paris

- March 15, 1934. Lot 55 sold by Christie’s (London) from the Derek (Editor’s note: Frederick?) Berry Collection, UK, for £85; $430, to Mr. R. Suenson-Taylor, UK

- June 1955. Owned by Lord Grantchester, barrister and financier. Sir Alfred Suenson-Taylor was created first Baron Grantchester, June 30, 1953

- 1961. Owned by Mamie Suenson-Taylor, Lady Grantchester, UK

- 1976. Owned by estate of Lord and Lady Grantchester. They died within months of each other

- Acquired by A La Vieille Russie, New York

- January 16, 1978. Sold by A La Vieille Russie to the Forbes Magazine Collection, New York, for $126,250

- February 2004. Sold privately as part of the Forbes Magazine Collection, New York, to Viktor Vekselberg, Moscow, for just over $100 million, according to the purchaser

- November 19, 2013. Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Fabergé made the hen of gold, set with rose-cut diamonds, arguing that it would look like bronze otherwise and would not be beautiful. The sapphire egg was held loosely in the hen’s beak, and the wicker basket was made of gold and apparently decorated with rose-cut diamonds. The whole consisted of one sapphire egg costing of 1800 rubles out of 2,986 rubles, 50 rose-cut diamonds 8/32, 60 rose-cut diamonds 14/32, 400 rose-cut diamonds 5¼; gold, and two cases. Diamond weights are given in the old systems used by European jewelers. Was the egg possibly dismantled for the value of its stones?

- April 5 (OS), 1886. Sent to Tsarskoe Selo by courier and presented to Tsar Alexander III

- April 13 (OS), 1886. Would have been presented to Marie Feodorovna, a gift from Alexander III; cost 2,986 rubles, 25 kopeks. Housed in the Anichkov Palace

- September 16-20 (OS), 1917. One of forty or so eggs sent to the Armoury Palace of the Kremlin in Moscow by the Kerensky Provisional Government for safekeeping

- 1922. May have been transferred to the Sovnarkom, the Council of People’s Commissars

- 2015. Whereabouts unknown. There is no known illustration of it.

(Courtesy Wartski)

The Russian State Historical Archives material cited by Marina Lopato (Apollo, January 1984) describes the egg as an …Easter egg with a clock, decorated with brilliants, sapphires and rose diamonds – 2160 rubles. In March 2014, Wartski’s website noted research by Tatiana Muntian on the record of transfer in September 1917 from the Anichkov Palace to the Moscow Kremlin Armoury: …Art. 1548. ˜A lady’s gold watch, opened and set into a gold egg with one diamond. The latter on a gold tripod pedestal with three sapphires.’ Number 1644. Muntian’s research cited in von Solodkoff, Fabergé: Juweiler des Zarenhofs (Hamburg, 1995), yielded another description of this egg. The 1919 inventory of confiscated Imperial treasure describes it as a …Gold egg with clock with a circle of brilliants, gold stand, with three sapphires and diamond roses. And the 1922 transfer documents of confiscated valuables from the Anichkov Palace to the Sovnarkom says: …Gold egg with clock with diamond pushpiece, on gold pedestal with 3 sapphires and rose-cut diamonds roses.

However, on July 6, 2011, Anna and Vincent Palmade reported at the Fabergé Forum in Richmond they had discovered a very good picture and detailed description of the missing 1887 Egg in the Parke Bernet auction catalogue for their New York sale of March 6-7, 1964 (lot 259). Although there were no mention of Fabergé in the catalogue description, they were able to match the picture and descritpion with the picture of the missing Egg in the von Dervis 1902 exhibition which they had found in November 2007, and which Annemiek Wintraecken was able to associate with the 1887 missing Egg in her revised timeline (November 2008). The description in the catalogue matches perfectly the description for the 1887 missing Egg in the archival documents (especially the references to the watch and the three sapphires):

It is the reference to the Vacheron & Constantin watch in the catalogue description which eventually led to the discovery of the Egg. In effect, the unsuspecting owner of the Egg once Googled the terms “egg” and “Vacheron Constantin” and found the article from the British newspaper “The Telegraph” (13 August 2011) referring to the discovery of the picture and description of the missing 1887 Egg in the 1964 Parke Bernet catalogue.

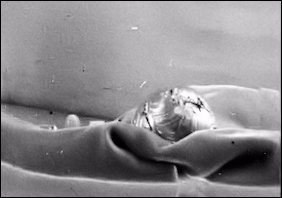

Then in March 2014, the London Fabergé dealer Wartski announced the Egg had been found. Wartski released the first color photographs of the Egg on its website, which describes the Egg thus:

Wartski advised they had purchased the Egg and sold it to an undisclosed bidder. In a flurry of word-wide newspaper articles, more specific details came to light. The first one written by Anita Singh for The Telegraph newspaper in London on March 18, 2014, based on an interview with Kieran McCarthy of Wartski carried the headline, The £20m Fabergé Egg That Was Almost Sold for Scrap.

An Internet publication, ecommercebytes.com reported on April 6, 2014:

In early 2015, thanks to two Russian scholars Drs. Galina Korneva and Tatiana Cheboksarova, an archival letter was found which had been written on May 4 (OS), 1887 by Modest Feopemtovich Solovyev, the Governor of the Office of Grand Duke Vladimir’s Court from 1881 to 1899, to Nikolai Stepanovich Petrov (1833-1913), who in 1887 was the Head of Cabinet of Alexander III. It reads:

By order of H.I.H. Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich an Easter egg with a clock and a stand in the style of Louis XVI was commissioned to the jeweler Fabergé. This egg is finished and was delivered to the Emperor. Today Fabergé sent an invoice of 2,160 rubles which H.I.H. commanded me to send to Your excellence. M. Solovyev.

Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich had been heavily involved in the creation of the First Hen Egg.

Kieran McCarthy of Wartski in a public lecture in English and Russian on June 4-5, 2015 at the Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia, gave his first-hand account of the rediscovery of the 1887 Third Imperial Easter.

- April 5 (OS), 1887. Would have been presented to Marie Feodorovna, a gift from Alexander III; cost 2,160 silver rubles. Housed in the Anichkov Palace

- September 16-20 (OS), 1917. One of forty or so eggs sent to the Armoury Palace of the Kremlin in Moscow by the Kerensky Provisional Government for safekeeping

- Between February 17-March 24, 1922. Transferred to the Sovnarkom, the Council of People’s Commissars, possibly bought by Hammer Galleries, New York

- March 6-7, 1964. Offered by Mrs. Rena Clark of New York at Parke-Bernet’s (New York) auction. Sold to a female buyer from the deep south of the US for $2,450

- ca. 2004. Bought for $14,000 by a scrap-metal dealer in the mid-west of the US

- 2014. Sold by this dealer to Wartski London and bought from them by an identified buyer for an undisclosed sum, estimated by market observers at about £20 million

Third Imperial Easter Egg by Fabergé Found! A Research Chronology compiled by Christel Ludewig McCanless, and published in Fabergé Research Newsletter, Summer 2014, summarized the history of the egg since 1887.

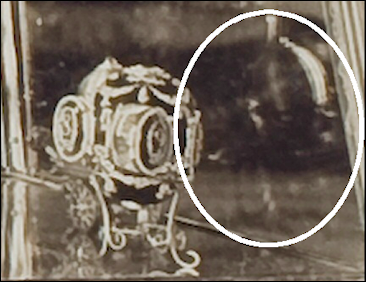

Maria Feodorovna Vitrine in von Dervis 1902 Exhibition with Egg and Its Reflection

(Archival Photographs)

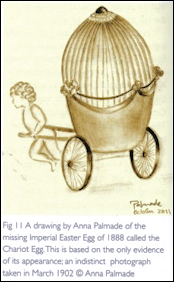

Anna Palmade Drawing and

Possible Prototype

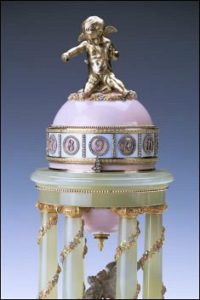

Cherub Egg with Chariot

(1888)

(Munn, Geoffrey, “Unscrambled Eggs”, Antique Collecting (UK), June 2015, 44)

Tatiana Muntian, in her article in von Solodkoff, Fabergé: Juwelier des Zarenhofes (Hamburg, 1995) cites the inventories made in 1917 and 1922 of confiscated Imperial treasure. The 1917 list includes the following: “… gold egg, decorated with brilliants, a sapphire; with a silver, golded [sic] stand in the form of a two-wheeled wagon with a putto.” Muntian claims 1885 as the date the egg was made, but in the opinion of these authors, it must surely be the 1888 egg. It may be significant that neither of these descriptions mentions a clock.

In November 2007, Anna and Vincent Palmade discovered the Egg in a picture of the von Dervis 1902 exhibition. The Egg had been unnoticed because it was hiding behind the Caucasus Egg in the picture. It was revealed through its blurry reflection in the vitrine.

- April 24 (OS), 1888. Would have been presented to Marie Feodorovna, a gift from Alexander III; cost 2,100 silver rubles

- March 1902 Shown in von Dervis exhibition (see illustrations above)

March 28 (OS), 1891. Housed at the Gatchina Palace - September 16-20 (OS), 1917. One of forty or so eggs sent to the Armoury Palace of the Kremlin in Moscow by the Kerensky Provisional Government for safekeeping

- February-March 1922. Transferred to the Sovnarkom, the Council of People’s Commissars

1930s. Possibly sold to Victor & Armand Hammer - September 26-27, 1941. Possibly part of lot 258 sold by Parke Bernet (New York) from the Collection of Mrs. Ethel Gunton Douglas of New York City, to an unknown buyer for $22.50 [sic]

- 2015. Whereabouts unknown

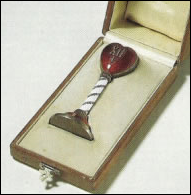

Pearl egg* – gold, rose-cut diamonds | Ring – gold, pearl

On page 3 of the file, dated February 22 (OS), 1889, a small egg-shaped leather case for the Easter egg is ordered, and on page 5, an account details one egg, one pearl 7.24/32 carats, five rose-cut diamonds, gold and double case, total cost 981 rubles, 20 kopeks. This figure of 981 rubles has been added in pencil to the bottom of the handwritten list of the Imperial Easter eggs from 1885 to 1890, made by N. Petrov, the assistant manager to the Cabinet of His Imperial Majesty. The list was found in the Russian State Historical Archives in St. Petersburg by Marina Lopato, and quoted in Apollo, January 1984 but these detailed descriptions do not agree with the invoice Fabergé sent to the Tsar on May 4 (OS), 1889, which details “1 Louis XV Nécessaire egg 1900 rubles”. (Fabergé, Proler, & Skurlov, Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs, London, 1997)

Tatiana Muntian says in von Solodkoff, Fabergé: Juwelier des Zarenhofes (Hamburg, 1995) that she found the following descriptions in the 1917 inventory of confiscated Imperial treasure: “gold egg/nécessaire, decorated with multi-colored stones and with brilliants, rubies, emeralds and sapphires.” Her fellow researcher, Valentin Skurlov, dated the egg at 1889, and the 1922 inventory of confiscated Imperial treasure concurs.

Tatiana Muntian says in her research published in von Solodkoff, Fabergé: Juwelier des Zarenhofes (Hamburg, 1995) the Resurrection Egg has no place in the list of Imperial Easter eggs presented by the Tsar. Her argument is convincing, especially in light of the Fabergé invoice, the inventory of confiscated Imperial treasure, and yet another description, noted when Marie Feodorovna took the egg from the Gatchina Palace to Moscow: “One item in the form of an egg, decorated with stones, containing ladies’ toilet articles, 13 pieces. Taken by the valet Ivoshkin when Their Majesties travelled to Moscow.” (Fabergé, Proler, & Skurlov, Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs, London, 1997)

This coincides almost precisely with the description of item number 20 in the Loan Exhibition of the Works of Carl Fabergé, which opened at Wartski London on November 8, 1949. Lent anonymously, the piece is described as “a Fine Gold Egg, richly set with diamonds, cabochon rubies, emeralds, a large colored diamond at top and a cabochon sapphire at point. The interior is designed as an Etui with thirteen gold and diamond set implements.” It would be the most extraordinary coincidence if these two eggs are not the same item, especially as Alexander III had stipulated there were to be no repetitions.

In March 2008, Kieran McCarthy of Wartski published material he had found in his employer’s files relating to lot 20 in the 1949 Wartski exhibition. The etui, which could well be the Nécessaire Egg, is partially shown on the bottom shelf of a display cabinet in a photograph taken at the exhibition. (Country Life, March 20, 2008, 60-61, excerpted in Fabergé Research Newsletter, The Missing Nécessaire Egg, April 2008 Anniversary Edition, and in Royal Russia, Annual no. 3, 2011, 92-93. McCarthy goes on to explain the item was lent anonymously for the exhibition and then in 1952 bought by Wartski’s who sold it the same year for £1200 to “a stranger.” McCarthy believes the purchaser was almost certainly British and that the current owners are unaware of its probable Imperial provenance.

There is as yet, no explanation regarding the original Pearl Egg*. The authors are of the view that the Pearl Egg, or the Pearl Egg pendant, as it is described by Fabergé, Proler, & Skurlov in Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs (London, 1997) was not the annual Easter gift from Alexander III to Marie Feodorovna. Apart from questions of dating arising with the Petrov list, Fabergé makes no mention of the egg pendant in his Easter bill to the Tsar. It seems possible initial plans were for the Pearl Egg to be the Easter gift, but that something happened which required the making of a second present, namely, the Nécessaire Egg. It should be noted both items were relatively inexpensive when compared with the cost of past and future Tsar Imperial Easter eggs.

- March 16 (OS), 1889. Pearl Egg presented to Alexander III at Gatchina Palace; cost 981 rubles, 20 copecks

- April 9 (OS), 1889. Nécessaire Egg would have been presented to Marie Fedorovna, a gift from Alexander III; cost 1,900 silver rubles

- March 28 (OS), 1891. Nécessaire Egg housed at the Gatchina Palace

- September 16-20 (OS), 1917. One of forty or so eggs sent to the Armoury Palace of the Kremlin in Moscow by the Kerensky Provisional Government for safekeeping

- February – March 1922. Transferred to the Sovnarkom, the Council of People’s Commissars

- Sold to a UK buyer

- June 19, 1949. Transferred from Wartski Llandudno, Wales, to Wartski, London, sold the same day to “a stranger” for £1,250

- 2015. Whereabouts of both eggs unknown; the Nécessaire Egg is possibly in a bank vault in the north of England

- December 2017. An amateur Fabergé sleuth, Kellie Bond found online the best image yet found of the Nécessaire Egg. See Daily Mail December 30, 2017, p. 3

(Keefe, John W., Masterworks of Fabergé:

The Matilda Geddings Gray Foundation Collection, 2008, 88-89)

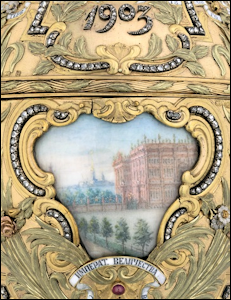

- Imperial yacht Polar Star

- Bernsdorff Palace, Copenhagen

- Kejserens Villa in Fredensborg Park

- Fredensborg Palace from the Marble Garden

- Schack Palace in the Amaliensborg Palace complex

- Kronborg Castle, Elsinore

- Two views of the Cottage Palace, Alexandreskii Park, Peterhof

- Gatchina Palace, near St. Petersburg

- Imperial yacht Tsarevna

The egg retains its original velvet case; the stand is modern.

And yet, existing literature dated the egg at 1895, probably because that date had been written in ink on the velvet case. We know from the memoirs of François Birbaum in von Habsburg & Lopato, Fabergé: Imperial Jeweller (London, 1993) Tsar Alexander III had laid down broad rules relating to the eggs: that the egg shapes continue, but that there be no repetitions. With this in mind, there surely cannot be two eggs in pink enamel in the Louis XVI style, especially within five years of each other. The date 1895 was probably written on the egg’s case during the 1922 inventory of confiscated Imperial treasure. It seems the real 1895 gift, the Blue Serpent Clock Egg, was not among the eggs listed in this inventory or that of 1917, and an assumption regarding the egg was made at that time. Proof that the Danish Palaces Egg was made before 1895 is available from a list made when the Imperial couple traveled, taking with them items from Gatchina Palace: “Egg consisting of 10 pieces (small folding screen). His Majesty took it to Petersburg on 31 December (OS), 1891, and returned it on 28 March (OS), 1892.” (Fabergé, Proler, & Skurlov, Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs, London, 1997) It is definitely identified in the 1917 inventory of confiscated Imperial treasure and possibly in the inventory made in 1922.

A 1932 scrapbook belonging to the Hammer Galleries further confuses the history of this egg by describing the egg as having twelve panels, not ten, and a cut and re-glued photograph shows the egg sitting in a wooden box, not in the original velvet case (Hammer Galleries Book I, 1932). The twelve-panel description is repeated in Compleat [sic] Collector, April 1943. To complicate matters further, the Hammer Galleries exhibition of 1939 has a photograph showing only ten frames, and showing the frames as the surprise for this egg. Despite all these varying descriptions, it now seems clear only ten miniatures ever existed. The scenes depicted on the miniatures were places familiar to Marie Feodorovna, and the yachts she used to travel in. For many years, the third panel of the Egg was wrongly identified as the estate of Hvidøre. Russian scholars Galina Korneva and Tatiana Cheboksarova identified in their publication, Empress Maria Feodorovna’s Favorite Residences in Russia and in Denmark (St. Petersburg, 2006) the palaces in the order listed above. Danish Fabergé enthusiast Christian Steener Eriksen had also noticed Marie Feodorovna and her sister Queen Alexandra of Great Britain had not bought the property until 1906, so a miniature of the residence could not have been included in an Easter gift made for 1890. On September 1, 1889, the New York Times reported:

In 2008 research by Annemiek Wintraecken and Steener Eriksen they found other documentation in which Alexander III expressed a wish in September 1885 to have his own residence in Fredensborg. Petrel’s Nest, a property in the palace gardens was bought, refurbished, and opened with a tea-party on October 1, 1889. Marie Feodorovna baptized the building and described it as ‘Our dear miniature Gatchina’. The house became known as the Kejserens Villa (Emperor’s Villa). In October 1980, the Egg was stolen while on exhibition at the Paine Art Center and Arboretum in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. It was recovered soon after, following a high-speed police pursuit, during which it was jettisoned with two other Tsar Imperial eggs, the 1893 Caucasus Egg and the 1912 Napoleonic Egg.

- March 30 (OS), 1890. Presented to Alexander III

- April 1 (OS), 1890. Would have been presented to Marie Feodorovna, a gift from Alexander III; cost 4,260 silver rubles

- January 31 (OS), 1893. Housed at the Gatchina Palace

- September 16-20 (OS), 1917. One of forty or so eggs sent to the Armoury Palace of the Kremlin in Moscow by the Kerensky Provisional Government for safekeeping

- February-March 1922. Probably transferred to the Sovnarkom, the Council of People’s Commissars

- June-July 1927. One of eight eggs returned by the Moscow Jewelers’ Union to the Armoury; given inventory no. 17553

- April 30, 1930. One of twelve eggs selected for export sale

- June 21, 1930. Transferred from the Armoury to the Antikvariat (Trade Department)

- 1930. One of ten Imperial eggs sold by the Antikvariat, Moscow, to Hammer Galleries, New York, for 1,500 rubles (ca. $750)

- ca. October 1935. Advertised by Hammer Galleries for $25,000

- February 1936. Advertised by Hammer Galleries

- November 1937-1953. Owned by Mr. & Mrs. Nicholas H. Ludwig, New York

- 1962. Private collection, United States

- June 8, 1971. Collection of the late Matilda Geddings Gray, oil heiress, Lake Charles and New Orleans, Louisiana

- 1972. Matilda Geddings Gray Foundation, New Orleans, Louisiana

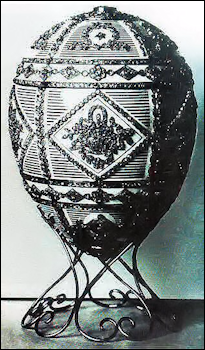

(Courtesy Armoury Museum, Moscow)

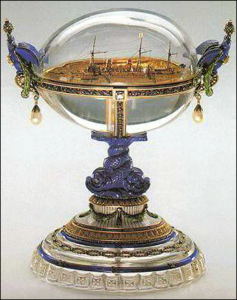

A second blow was parried by Prince George of Greece, the second son of King George I of Greece, who fended off the attack with his cane. George, a boyhood friend of Nicholas, had joined the eastern adventure in Athens, where the Russian princes stopped before traveling east. Nicholas told Marie Feodorovna: “I stopped and turned round and to see dear Georgie about ten paces from me, with the policeman, whom he had knocked to the ground with one blow of his cane, laying at his feet. Had Georgie not been in the rickshaw behind me, dearest Mama, perhaps I would never have seen you again!” Nicholas was left permanently scarred both physically and mentally, and the incident poisoned his view of the Japanese, whom he described in private as “monkeys.” The Ōtsu incident probably played a role in the Tsar’s ill-fated decision to go to war against the Japanese 13 years later. Blood from a handkerchief used to staunch the Tsesarevich’s wound was used 100 years later in the earliest DNA testing done to positively identify the body of Nicholas II.

Grand Duke George’s lung condition appeared to worsen, and he had already returned to Russia before Nicholas arrived in Japan. Tatiana Muntian has observed that “For people familiar with the unfortunate journey, the blood-red drops in the heliotrope and the bright red ruby of the knob had a sinister meaning”. (Muntian, et al. World of Fabergé, Moscow, 1996) Seven years later, she saw further symbolism in the egg:

The cruiser In Memory of the Azov was named in honor of the Azov, the first Russian battleship to be awarded the St. George flag. It won the honor for its role in the Battle of Navarino in 1827. A letter written by Eugène Fabergé on June 5, 1934, says the miniature was made “by the old (Editor’s note: August) Holmström, who especially put all his art into making the tiny ship as natural as possible so that the guns were movable and all the rigging exactly copied. Even the chains of the anchors were movable.” (Fabergé, Proler, & Skurlov, Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs, London, 1997)

As stated above, this was one of the Tsar Imperial eggs which traveled from St. Petersburg and was returned to Gatchina Palace. In 1900, it was exhibited at the Exposition Internationale Universelle in Paris in 1900, along with the 1898 Lilies of the Valley, the 1899 Pansy, the 1897 Coronation, the 1900 Trans-Siberian Railway Eggs, and possibly the 1890 Danish Palaces Egg. But the 1891 Memory of Azov Egg did not impress the French judge, René Chanteclair:

Other judges, including Victor Champier and the noted enameller Louis Houillon, were more enthusiastic about Fabergé’s work. In any event, the Exposition brought Fabergé and his work to the notice of the world.

The Memory of Azov Egg is readily identifiable in both the 1917 and 1922 inventories of confiscated Imperial treasure. An expert valuation was made of this egg in 1927. Found by Fabergé, Proler, & Skurlov, the valuation noted the mast was damaged, one rose-cut diamond was missing, and there was “a noticeable crack in the jasper.” The egg’s worth was assessed at 8,880 rubles. With the 1902 Clover Leaf and 1906 Moscow Kremlin Eggs, this egg was scheduled for sale to the West. They were returned to the Armoury, following protests from workers and management within the Armoury.

- April 21 (OS), 1891. Would have been presented to Marie Feodorovna, a gift from Alexander III; cost 4,500 silver rubles

- November 27 (OS), 1891. Housed at the Gatchina Palace

- September 16-20 (OS), 1917. One of forty or so eggs sent to the Armoury Palace of the Kremlin in Moscow by the Kerensky Provisional Government for safekeeping

- February-March 1922. Transferred to the Sovnarkom, the Council of People’s Commissars

- June 17, 1927. One of sixteen eggs transferred from the Foreign Currency Fund of the Narkomfin (Finance Ministry) to the Armoury; given inventory no. 17536

- 1933. Was to be offered for sale at 20,000 rubles, but retained in the Armoury Museum, Moscow

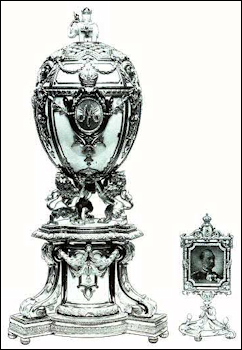

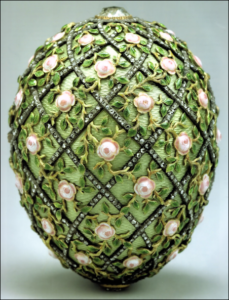

Diamond Trellis Egg in Maria Feodorovna’s

Exhibit Case, 1902 von Dervis Mansion Venue,

St. Petersburg, Russia

(Archival Photograph)

Egg Missing Its Surprise with Putti

Base, Sotheby’s London, 1960

(Archival Photograph)

Egg Missing Its Surprise and Base

(Courtesy McFerrin Collection)

“The Egg is lined with white satin with a space for the figure of an elephant and a key for winding 1 Ivory figure of an elephant, clockwork, with a small gold tower; partly enameled and decorated with rose-cut diamonds, on its back; the sides of the figure bearing gold decorations in the form of two crosses, each with five precious stones. The elephant’s forehead is decorated with the same kind of stone. The tusks, trunk and harness are decorated with small rose-cut diamonds, and a black mahout is seated on its head.” (Fabergé, Proler, Skurlov, Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs, London, 1997)

The elephant mentioned was the surprise inside the egg. At present, the egg exists alone in the Dorothy and Artie McFerrin Collection. The pedestal is either lost or survives elsewhere. The pedestal, but not the surprise, was still with the egg when it was sold by Sotheby’s London, on December 5, 1960. The catalog description includes the line …supported on the backs of three silver putti who are seated on a grassy mound ¦ There is an accompanying illustration of the egg with its pedestal of three silver putti. Toby Faber in Fabergé Eggs: The Extraordinary Story of the Masterpieces that Outlived an Empire (London, 2008) says the Diamond Trellis Egg was …subsequently separated from its genuine stand by Emanuel Snowman in [the] mistaken belief that this was a later addition. The elephant appears on the coat of arms of the Danish Royal family, and Marie, of course, was a Danish princess. The reference to the elephant being …clockwork suggests it was the first automaton used by Fabergé in a Tsar Imperial egg.

On October 10, 2015, the Curator of Queen Elizabeth II’s Fabergé collection, Caroline de Guitaut confirmed to the Lapidary Art Symposium at the St. Petersburg Fabergé Museum that an ivory automaton elephant in the Royal Collection matches the known descriptions of the Diamond Trellis Egg’s surprise. In consultation with Dorothy and Artie McFerrin, it was determined the miniature elephant fits the Diamond Trellis Egg. Ms. de Guitaut explained: “A fragment of the elephant’s turret was lost. It seems it had just fallen off due to the aged metal. Yet as a result, it was possible to look into the foundation of the figure. When we removed the top part of the turret, my heart nearly stopped beating: It contained the Fabergé hallmark! That is how we found the proof of the discovery’s authenticity.” She continued: “The newly discovered automaton surprise is almost identical to the badge of the Danish Order of the Elephant, the most senior order of chivalry in Denmark, except that it is made of ivory rather than white enamel and that it incorporates a mechanism. The elephant is wound with a watch key through a hole hidden underneath the diamond cross on one side of the elephant. It walks tentatively on ratcheted wheels and lifts its head up and down.” (See Royal Collection Trust video)

Apart from being the first known automaton surprise used in a Tsar Imperial Easter Egg, this mechanical elephant is seemingly among the first automata made by Fabergé. In comparison with the mechanical devices used in the 1906 Swan and 1908 Peacock Eggs, this automaton is almost primitive. But it is yet another example of Fabergé and his workforce trying something new and which, over time would be extensively and exquisitely refined. The automaton elephant this theme would be repeated eight years later in the 1900 Pine Cone Egg made for Barbara Kelch, neé Bazanova ,was the daughter of an extremely wealthy Moscow merchant family. In 1894, she married Alexander Ferdinandovich Kelch, a titled gold magnate and industrialist. In the years from 1898 to 1904, Kelch presented to his wife eggs quite on a par with their Imperial counterparts.

Tatiana Muntian’s research in von Solodkoff, Fabergé: Juwelier des Zarenhofes (Hamburg, 1995) quotes the 1917 inventory of confiscated Imperial treasure as including the …brilliant grill (-work/trellis) egg of 1892 – an egg of nephrite in gold setting, with a brilliant-covered net, base of nephrite with three silver putti. The 1922 inventory of confiscated Imperial treasure includes as a separate entry, …Ivory model of an elephant in gold setting with rose-cut diamonds and diamonds. According to Caroline de Guitaut, the newly discovered automaton surprise is almost identical to the badge of the Danish Order of the Elephant, the most senior order of chivalry in Denmark, except it is made of ivory rather than white enamel and incorporates a mechanism. The elephant is wound with a watch key through a hole hidden underneath the diamond cross on one side of the elephant. It walks on ratcheted wheels and lifts its head up and down.

It is possible the Diamond Trellis Egg is one of two Fabergé eggs referred to in an article by Alexander Mosyakin, …The Sale: Our Country’s Great Loss, in the Moscow newspaper Ogonyok, No. 7, February 1989. Mosyakin refers to two eggs both of …jadeite (sic) with dozens of brilliants being sold for $450 each. This sparse comment could be a rough description of the Diamond Trellis Egg. The description probably should refer to rose-cut diamonds, not brilliants. However, it is difficult to see how an egg with …dozens of brilliants could be worth only $450.

- April 5 (OS), 1892. Would have been presented to Marie Feodorovna, a gift from Alexander III; cost 4,750 silver rubles

- 1893? Housed at the Gatchina Palace

- September 16-20 (OS), 1917. One of forty or so eggs sent to the Armoury Palace of the Kremlin in Moscow by the Kerensky Provisional Government for safekeeping

- February-March 1922. Transferred to the Sovnarkom, the Council of People’s Commissars

- ca. 1927. Probably sold to Michel Norman of the Paris-based Australian Pearl Company or his associate Norman Weisz, by officials of the Antikvariat (Trade Department)

- Sold to Emanuel Snowman of Wartski, London

- 1929. Transferred from Wartski, Llandudno, Wales to Wartski, London, having been purchased for £125

- October 19, 1929. Bought from Wartski by T. B. Kitson, UK for £260

- December 5, 1960. Lot 92 sold by Sotheby’s London from the Collection of the late T. B. Kitson, UK, to buyer’s agent, Drager, for £2,400, $6744

- 1962-77. Private collection, UK

- May 1983. Private collection, London

- 1985. Private collection, US

- April 11, 2003. Lot 101 offered by Christie’s New York from a private American collection, passed at $1,300,000

- 2012. Dorothy & Artie McFerrin Collection, Houston Museum of Natural Science, Texas

Elephant Surprise:

- 1927-29: With Wartski; likely purchased separately from the Egg

- 1935. Sold to King George V, London, and possibly a gift for Queen Mary

- 2015. The Royal Collection, London

Caucasus Egg

(Keefe, Masterpieces of Faberge: The Matilda

Gray Foundation Collection, 2008, 84)

Early research suggested the images were of the Imperial Hunting Lodge, and this view was accepted through the 20th century. However, new and diligent research by Fabergé sleuth Annemiek Wintraecken indicates there was no Imperial hunting lodge per se in Abastuman, Georgia. The miniatures represent two houses especially built for Grand Duke George Alexandrovich when Abastuman was chosen as the place for him to live because of his tuberculosis, a water fall, and tents. Her archival research on the miniatures has discovered:

“1” House

(Keefe, Masterworks of Fabergé:

The Matilda Geddings Gray

Foundation Collection, 2008, 82)

“9” Tents

“3” House

(Keefe, Masterpieces of Fabergé:

The Matilda Geddings Gray Foundation Collection, 1993, 130)

Miniature ‘8’ illustrates the ‘spa-like’ nature of the area. In 1886, an electro-therapy facility with two bathrooms was opened with water coming directly from one of the three wells in the village. The Remmert Bridge over the waterfall depicted on one of the miniatures is named after Dr. Adolf Alexandrovich Remmert, born 1835 in St. Petersburg and buried 1902 in Abastuman.

Miniature ‘9’ shows some tents in the woods. They were probably in use in 1891 when Krijitski painted the miniature. The tents puzzled me until I read about the ‘open air treatment’ for tuberculosis, since there was at the time no cure for this illness. Although Robert Koch (1843-1910), German physician and microbiologist, had identified the cause for tuberculosis in 1882, only in the next century did drugs became available for treatment. In the interim it was generally believed fresh air, rest, and sunshine were the major components in treating tuberculosis and a tent was the closest thing to living outside.

Miniature ‘3’ shows the ‘Summer Palace’ in its early state with only one floor. Later the house was modified and a second floor was added. George’s presence in Abastuman made the resort more popular and many nobles visited the Georgian village, including all members of the Tsar’s family, including his mother Marie Feodorovna and Tsar Nicholas II himself.

The Caucasas Egg is supported on a faux-bentwood scrolled gold stand which is not original. In 1938, the egg retained its original white velvet case, marked with its Armoury inventory number.

After the sudden death of Alexander III in 1894, Nicholas II ascended the throne. At the time, he had no male heir, so his younger brother George Alexandrovich became the heir and Tsesarevich. Grand Duke George was outgoing, like his mother Marie Feodorovna, and considered the cleverest of the Imperial children. A naval career was planned, before he contracted tuberculosis in 1890. In the same year, Tsar Alexander III and Marie Feodorovna sent Grand Duke George on a nine-month Asian tour, as a companion to his brother, the Tsesarevich Nicholas. But signs of ill-health in India forced George to return home. The Empress was told he had a fever, but in fact, he had contracted acute bronchitis. He was sent to Abastuman to recover. In 1895, during a rare trip away to visit his mother’s relatives in Denmark his condition deteriorated.

George died on August 9 (OS), 1899. Despite his doctors’ orders, he had been out alone on his motor-cycle and some hours later, when he failed to return, his worried staff sent out a search party. A peasant woman had discovered him collapsed at the side of the road, blood oozing from his mouth as he struggled to breathe. She supported him in her arms until he died. Marie Feodorovna spent hours interrogating the woman. The Dowager Empress sent a telegram to Queen Victoria saying: “My poor dearest son passed away quite alone. Am heartbroken.”

The Caucasus Egg is listed in the 1917 inventory of confiscated Imperial treasure: “Gold egg, covered with red enamel and diamond decorations in medallions with pearl and diamonds.” The 1922 inventory of confiscated Imperial treasure lists “1 gold egg with 2 (portrait) diamonds and rose-cut diamonds, covered with portraits and landscapes”, which is probably the Caucasus Egg. An expert valuation was made of this egg in 1927. Found by Fabergé, Proler, & Skurlov (Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs, London, 1997), the valuation noted the enamel was chipped in three places and one rose-diamond setting was empty. The valuation assessed the egg’s worth at 9,906 rubles.

The Egg was stolen while on exhibition at the Paine Art Center and Arboretum in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, in October 1980. It was recovered soon after, following a high-speed police pursuit, during which it was jettisoned with two other Tsar Imperial eggs, the 1890 Danish Palaces Egg and the 1912 Napoleonic Egg. The Caucasus Egg sustained some enamel damage, which has since been expertly repaired.

- March 28 (OS), 1893. Would have been presented to Marie Feodorovna, a gift from Alexander III; cost 5,200 silver rubles. Housed in the Anichkov Palace

- September 16-20 (OS), 1917. One of forty or so eggs sent to the Armoury Palace of the Kremlin in Moscow by the Kerensky Provisional Government for safekeeping

- February-March 1922. Transferred to the Sovnarkom, the Council of People’s Commissars

- June 17, 1927. One of sixteen eggs returned by the Foreign Currency Fund of the Narkomfin (the Finance Ministry) to the Armoury; given inventory no. 17537

- April 30, 1930. One of twelve eggs selected for export sale

- June 21, 1930. Transferred from the Armoury to the Antikvariat (Trade Department)

- 1930. One of ten Imperial eggs sold by the Antikvariat, Moscow, to Hammer Galleries, New York, for 5,000 rubles (ca. $2,500)

- April 1937. Advertised by Hammer Galleries

- November 22, 1937. First public showing in the United States, in New York

- Early 1940s. Advertised by Hammer Galleries for $35,000

- April 1943. Displayed in Hammer Galleries, New York

- 1947. Owned by Hammer Galleries, New York

- 1950s. Possibly owned by Jack & Belle Linsky, stapler fortune, New York

- ca. 1959. Bought by Matilda Geddings Gray, oil heiress, Lake Charles and New Orleans, Louisiana

- June 8, 1971. In Collection of the late Matilda Geddings Gray

- 1972. Matilda Geddings Gray Foundation, New Orleans, Louisiana

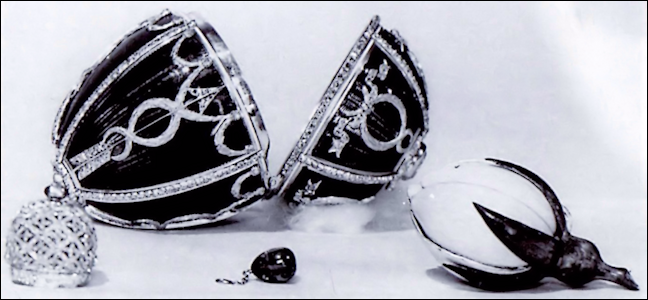

LEFT EGG: 18th Century Casket by LeRoy | RIGHT EGG: Fabergé Renaissance Egg (Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia)

(LEFT PICTURE: Photograph © Géza von Habsburg | RIGHT PICTURE: Courtesy Green Vault, Dresden, Germany)

- April 17 (OS), 1894. Would have been presented to Marie Feodorovna, a gift from Alexander III; cost 4,750 silver rubles. Housed in the Anichkov Palace

- September 16-20 (OS), 1917. One of forty or so eggs sent to the Armoury Palace of the Kremlin in Moscow by the Kerensky Provisional Government for safekeeping

- February-March 1922. Probably transferred to the Sovnarkom, the Council of People’s Commissars

- June-July 1927. One of eight eggs returned by the Moscow Jewelers’ Union to the Armoury; given inventory no. 17552

- April 30, 1930. One of twelve eggs selected for export sale

- June 21, 1930. Transferred from the Armoury to the Antikvariat (Trade Department)

- 1930. One of ten Imperial eggs sold by the Antikvariat, Moscow, to Hammer Galleries, New York, for 1,000 rubles (ca. $500)

- May 1937. Advertised by Hammer Galleries

- November 1937-1947. Owned by Henry Talbot de Vere Clifton, millionaire landowner, sportsman, and poet, UK

- November 1949. Owned by Jack & Belle Linsky, stapler fortune, New York

- 1958. Sold by Jack & Belle Linsky to A La Vielle Russie, New York

- March 1959. Advertised by A La Vieille Russie, New York for $50,000

- May 1960. Advertised by A La Vieille Russie, New York

- 1962. Owned by Alexander Schaffer of A La Vieille Russie, New York

- June 1, 1966. Sold by A La Vieille Russie, New York to Forbes Magazine Collection for $78,750

- February 2004. Sold privately as part of the Forbes Magazine Collection, New York, to Viktor Vekselberg, Moscow, for just over $100 million, according to the purchaser

- November 19, 2013. Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Tsar Alexander III (1845-1894) and His Consort Marie Feodorovna (1847-1928)

(Wiki)

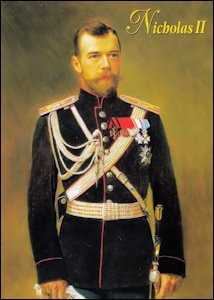

Tsar Nicholas II (1868-1918) and His Consort Alexandra Feodorovna (1872-1918)

(Source: Royal Russia News, Wiki)

Blue Serpent Clock Egg

(Courtesy Cleveland

Museum of Art)

Duchess of

Marlborough Egg

(Courtesy Fabergé

Museum, St.

Petersburg, Russia)

- A. Kenneth Snowman, whose family company Wartski had had a long association with the Blue Serpent Clock Egg put its date at 1887.

- A handwritten list of the Imperial Easter eggs from 1885 to 1890 made by N. Petrov, the assistant manager to the Cabinet of His Imperial Majesty, and found in the Russian State Historical Archives in St. Petersburg, has a clock egg as the Imperial Easter gift for 1887.

- Marina Lopato, quoting the list in an article in Apollo (January 1984), thought these were one and the same. However, Lopato, in a later article in von Habsburg & Lopato, Fabergé: Imperial Jeweller (London, 1993), wrote that the Blue Serpent Clock Egg would have cost closer to 6,000 rubles, not the 2,160 silver rubles listed for the 1887 gift. She also believed the Blue Serpent Clock Egg was too sophisticated for this relatively early date. The gold markings of the latter limited its production to no later than 1898.

- 1992. Wartski exhibition, Fabergé from Private Collections includes the Blue Serpent Clock Egg, out of sight since 1972 was loaned by Prince Rainier III of Monaco.

- But Tatiana Muntian in von Solodkoff, Fabergé: Juwelier des Zarenhofes (Hamburg, 1995) aligned this egg with the descriptions for the 1887 gift. And Fabergé, Proler, & Skurlov in Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs (London, 1997), confirmed the date as 1887.

- 2001. Lowes and McCanless in Fabergé Eggs: A Retrospective Encyclopedia also found it difficult to accept that the Easter egg series evolved from a simple hen egg to this elaborate gift in just two years.

- 2008. Blue Serpent Clock Egg unveiled through the joint efforts of the Cleveland (Ohio) Museum of Art and the Consulate General of Monaco in New York City. In the article, “The Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs: New Discoveries Revise Timeline” by Annemiek Wintraecken, the author after a challenge by Dr. Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm reports on her discovery that the invoice of the 1895 Twelve Monogram Egg (now known as the 1896 Alexander III Portraits Egg) also fits the Blue Serpent Clock Egg. It reads: “Blue enamel egg, Louis XVI style, 4500 rubles.”

Highlights from Wintraecken’s research summary include:

- Tillander-Godenhielm confirming the Blue Serpent Clock Egg is in the Louis XVI style and, although the former Twelve Monogram Egg/now Alexander III Portraits Egg has elements of that style, the egg is not in the Louis XVI style.

- Marina Lopato in her 1993 essay, “A Few Remarks Regarding Imperial Easter Eggs”, states: “Neither the indicated price … nor the style corresponds to such an early date (i.e., 1887, now occupied by the Third Imperial Egg)” and “The gold markings of the Blue Serpent Clock Egg limit its production to no later than 1895/1896.”

Wintraecken began thinking about the amount of time Fabergé had to make this egg, in view of the death of Tsar Alexander III on November 1 [NS], 1894, and she concluded the Fabergé workshop probably started right after Easter in April 1894 on Marie Feodorovna’s egg. François Birbaum, Fabergé’s head workmaster, states in his memoirs: “The process of making these eggs usually took about one year. Work started soon after Easter, and they were only just ready for Holy Week of the following year”. She concluded, if one of the two 1895 eggs was to be a relatively simple one, it could not have been the Dowager Empress’ egg; it was the 1895 Rosebud Egg for Tsarina Alexandra Feodorovna for which there was barely half a year to make it. Based on the above, I concluded the Fabergé invoice of the 1895 could be the invoice of the Blue Serpent Clock Egg.”

Fabergé created a very similar egg for Consuelo Vanderbilt, the Duchess of Marlborough, in 1902. The latter egg, known as the Duchess of Marlborough Egg, is larger and has a lustrous pink enamel. Several inspirations and prototypes of the Blue Serpent Clock Egg have been suggested.

- April 2 (OS), 1895. Would have been presented to Marie Feodorovna, a gift from Alexander III; cost 4,500 silver rubles. Housed in the Anichkov Palace

- September 16-20 (OS), 1917. One of forty or so eggs sent to the Armoury Palace of the Kremlin in Moscow by the Kerensky Provisional Government for safekeeping

- February-March 1922. Probably transferred to the Sovnarkom, the Council of People’s Commissars

- ca. 1927. Bought by Michel Norman of the Paris-based Australian Pearl Company, probably from Russian officials of the Antikvariat

- October 2, 1950. Bought by Emanuel Snowman of Wartski, London, from the Australian Pearl Company for £3,750

- 1950-72. In collection of Messrs. Wartski, London

- December 23, 1972. Sold by Wartski to shipping magnate, Stavros Niarchos for £64,103

- May 7, 1974. Presented by Stavros Niarchos as a gift to Prince Rainier III to mark his 25th anniversary as Monaco’s sovereign prince

- 1992. Owned by Prince Rainier III of Monaco

- April 6, 2005. Inherited by Prince Albert II of Monaco

Archival Photograph

(Courtesy Wartski)

(Courtesy Fabergé Museum,

St. Petersburg, Russia)

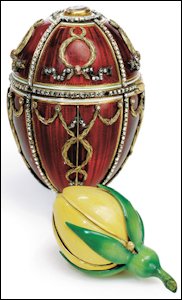

The egg, lined with cream velvet, opens to reveal a gold-hinged rosebud of matt green and yellow enamel, which once contained two tiny surprises-a miniature replica of the Imperial crown set with diamonds and rubies, and a ruby pendant hanging within it. Tatiana Muntian (von Solodkoff, Fabergé: Juwelier des Zarenhofes, Hamburg, 1995) found the 1922 inventory of confiscated Imperial treasure included the following description: “gold egg with brilliants and diamond roses, inside a flower, crown out of diamond roses.”

Fabergé, Proler and Skurlov (1997) say the tsarina kept the egg at the Winter Palace, where it was displayed on the second shelf from the top in the corner showcase between the door leading into the bedroom and the window. They also cite the inventory of Imperial family’s private quarters by N. Dementiev, Inspector of Premises of the Imperial Winter Palace, made on April 10 (OS), 1909:

The egg was among Imperial property appropriated in 1917 and is listed in the 1922 inventory of items sent to the Sovnarkom: “1 gold egg with diamonds and rose-cut diamonds, containing a flower and a crown of rose-cut diamonds.” As with the 1885 Tsar Imperial First Hen Egg, the two smaller surprises, the replica of the Imperial crown and the ruby pendant, were separated from the host egg, probably in the late 1930s. These two surprises are known only from archival Fabergé photographs. The entry for this egg in the catalog for the Exhibition of Russian Art, held in Belgrave Square in 1935, says: “Enamel, diamond and gold, with rose-bud containing Imperial crown, which contains a drop ruby” indicating that at least one of the two smaller surprises was still in the egg at that time.

The egg was lost from public view for four decades, during which time rumors abounded it had been destroyed by its owner. In fact, the egg sustained some enamel damage when it was reputedly thrown during a marital dispute. It has since been expertly repaired.

- April 2 (OS), 1895. Would have been presented to Alexandra Feodorovna, a gift from Nicholas II; cost 3,250 silver rubles

- April 10 (OS), 1909. Housed in Alexandra Feodorovna’s study in the Winter Palace

- September 16-20 (OS), 1917. One of forty or so eggs sent to the Armoury Palace of the Kremlin in Moscow by the Kerensky Provisional Government for safekeeping

- February-March 1922. Transferred to the Sovnarkom, the Council of People’s Commissars

- ca. 1925. Transferred to the Antikvariat (Trade Department)

- ca. 1927. One of nine Imperial eggs sold by the Antikvariat, Moscow, to Emanuel Snowman of Wartski

- October 27, 1934. Sold by Wartski, London, to Charles Parsons for £525

- June 1935. Owned by Charles Parsons, London

- ca. 1937. Bought by Henry Talbot de Vere Clifton, millionaire landowner, sportsman, and poet, UK

- 1941-42. Sold in the US by Henry Talbot de Vere Clifton

- 1962. Whereabouts unknown

- August 15, 1985. Fine Art Society, London, negotiated sale to Forbes Magazine Collection, New York for $525,000

- February 2004. Sold privately as part of the Forbes Magazine Collection, New York, to Viktor Vekselberg, Moscow, for just over $100 million, according to the purchaser

- November 19, 2013. Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

(Courtesy Hillwood Estate,

Museum and Gardens)

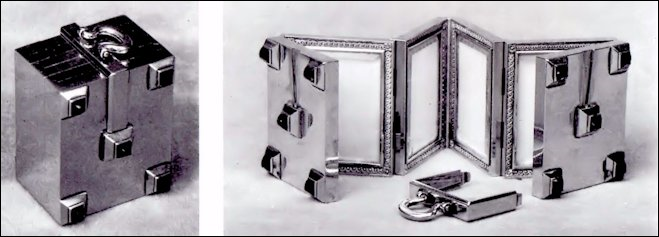

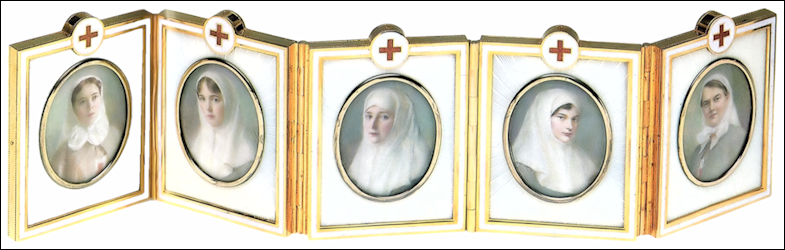

Missing Folding Miniature Frame Surprise Without Alexander III Miniatures by Zehngraf

(Snowman, A. Kenneth, Carl Fabergé, Goldsmith to the Imperial Court of Russia, 1979, 56)

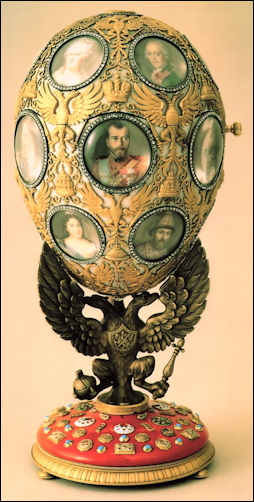

The egg opens to reveal a velvet lining for the missing surprise. Fabergé’s invoice describes the Egg: “Blue enamel egg, 6 portraits of H.I.M. Emperor Alexander III, with 10 sapphires and rose-cut diamonds and mounting. (Fabergé, Proler, & Skurlov, Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs, London, 1997) Christopher Forbes says the accompanying stand is modern. Another stand was made for the egg for the Russian Enamels: Kievan Rus to Fabergé exhibition in Baltimore, Maryland, November 17, 1996 – February 23, 1997.

This Egg is of relatively simple design, and may have been a deliberate calculation by Fabergé. The now Dowager Empress Marie Feodorovna was genuinely grief-stricken that her tall, immensely strong and determined husband, had died so young – he was 49. An elaborate memorial gift at this time would have only added to the young widow’s intense sorrow. Three more sophisticated memorial eggs to Alexander III would follow in future years.

Tatiana Muntian gives an insight into an incident involving the late arrival of the always much-anticipated Easter gifts: “In 1896, the Emperor – who was angry with the jeweler for he had delivered an Easter present late – in a letter to his mother who was in France, called him ‘foolish Fabergé’.” (Muntian, T.N., Fabergé Easter Gifts, Moscow, 2003) The Dowager Empress was attending her second son, George, in the south of France. Grand Duke George, suffering from tuberculosis, was staying at La Turbie, a picturesque village perched above Monte Carlo. Géza von Habsburg (Fabergé: Treasures of Imperial Russia, New York, 2004) expands on the incident, reporting the following exchange of letters between Nicholas II and Marie: “You will by post be receiving a little parcel – it is from me. That silly man Fabergé came too late to send it by courier.” From La Turbie, Marie replied:

Nicholas calmed down and, pleased with his mother’s response, he wrote back: “It was a great joy to me that you liked the egg – the miniatures of dear Papa are really successfully done and are good likenesses.” (Géza von Habsburg, in Fabergé: Treasures of Imperial Russia, New York, 2004). Two other eggs arrived late. In 1900, the Cockerel Egg was delivered to Marie’s Gatchina Palace outside St. Petersburg, when the Dowager Empress was in fact, in Moscow. And the 1909 egg was late arriving in London when Marie was staying at Buckingham Palace with her sister, Queen Alexandra.

There is no obvious reference to the Alexander III Portraits Egg in either the 1917 or 1922 inventories of confiscated Imperial treasure. Russian research indicates Alexandra Feodorovna actually helped pay for the cost of the egg. This was the only time she did this, and it was done before the two women became fully estranged. How the Egg found its way to the West remains unknown.

Fabergé researchers Anna and Vincent Palmade writing in the Fabergé Research Newsletter, Winter 2014, shared an exciting discovery – “1896 Alexander III Portraits Egg – Missing Surprise Identified in Photographs”. The frames, predictive of the ‘style moderne,’ were bought by Wartski for 420 guineas. Wartski images of the frames, which fold together into a neat ‘case’ with a handle above, are illustrated above. However, the portraits of the late Tsar in uniform had been removed, probably by the family before the item was offered at auction. The frames holding the miniatures are listed in the 1935 Belgrave Square exhibition catalog as being by Fabergé. Johannes Zehngraf, coincidentally, painted the miniatures for the Egg with Revolving Miniatures made in this year for Alexandra Feodorovna. Fabergé enthusiasts are searching for six miniatures (ca. 1.5 in. high x 1 in. wide) by Johannes Zehngraf of the ‘Emperor Alexander III in different uniforms’ which fit the folding frame surprise.

The Hillwood Museum staff tested a replica of the surprise inside the Alexander III Portraits Egg. The replica ‘chain’ of portrait miniatures was made using the dimensions and illustrations of the surprise. They fitted inside the egg so perfectly that they could barely move within their confines. The four top corners of the folded screen matched exactly the four marks on the velvet inside the upper part of the Egg. A news release (April 15, 2014) by the museum announced the re-dating to the egg which is now illustrated on the Hillwood Museum website in never-before-seen photographs.

- After March 24 (OS), 1896. Would have been presented to Marie Feodorovna, a gift from Nicholas II; cost 3,575 silver rubles. Housed in the Anichkov Palace. Probably sold to a Paris-based jeweler by Russian officials owned by Mrs. Andrea Bell Berchielly, Italy

- June 14, 1949. Bought by Marjorie Merriweather Post, General Foods heiress, as Mrs. Joseph E. Davies, from Mrs. Berchielly for the equivalent of $1739.13

- 1958. Owned by Mrs. Post as Mrs. Herbert May

- September 12, 1973. Collection of the late Marjorie Merriweather Post, at Hillwood Estates, Museum, and Gardens Washington (DC)

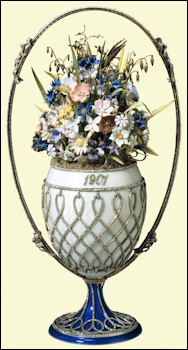

Twelve miniature paintings, ten signed by Johannes Zehngraf, are framed in chased gold guilloché. They revolve around a fluted gold shaft that passes vertically through the center of the egg when the cabochon emerald at the top is depressed and turned. At this time, a hook is lowered and engages the top of a miniature to revolve on the gold axis. The hook folds them back like the pages of a book, so two of the miniatures can be fully seen. Each miniature represents a place of significance in the tsarina’s life:

Kranichstein Castle in Hesse, Germany, where Alix spent some summer holidays in her youth.

Altes Palais (Editor’s note: Old Grand Ducal Palace) in Darmstadt, was the official residence of Alix’s father, Ludwig IV, Grand Duke of Hesse. It was here that Alix spent much of her childhood after her mother died when Alix was six.

Rosenau in Coburg, Germany. In April 1894, Alix’s brother, Ernest, the Grand Duke of Hesse, married Victoria Melita of Saxe-Coburg in the Palace Church of Coburg. The Tsesarevich Nicholas attended the wedding, and four days later Princess Alix accepted his proposal of marriage. The next day, they drove in a pony-cart to nearby Rosenau.

Alexander Palace at Tsarskoe Selo, twelve miles from St. Petersburg. This relatively modest palace became the couple’s favorite winter residence.

Anichkov Palace in St. Petersburg. After their marriage on November 14 (OS), 1894, the newlyweds lived in a suite of six small rooms, an extension of the new tsar’s bachelor quarters in this palace, a residence of the Dowager Empress Marie.

Winter Palace in St. Petersburg. It was in this vast and inhospitable palace that Nicholas and Alexandra were married. The miniature reflects the dull red color of the palace’s facade as it looked at this time. Originally painted turquoise and white, the facade in the early twenty-first century was sea-green and white.

Wolfsgarten, near Darmstadt, Germany. This villa was used as a hunting lodge and was visited by Alix on occasion during the summers of her youth. It was here that she received instruction before her conversion to Russian Orthodoxy, a necessary requirement for a future tsarina of Russia.

Palace Church in Coburg, Germany. See Rosenau above.

Windsor Castle, near London. Alix was a frequent visitor to the ancient castle at Windsor, the primary residence of her grandmother, Queen Victoria. Alix and Nicholas visited Queen Victoria at Windsor in July 1894.

Balmoral Castle, Scotland. Alix and her family made annual trips in her childhood to Britain. They would visit Queen Victoria at Balmoral during the shooting season. Nicholas and Alexandra visited Balmoral in October 1896.

Osborne House, the Isle of Wight. Nicholas visited Britain in the summer of 1894 and stayed with his fiancée and her grandmother at Osborne House in June of that year. The mansion, built in the 1840s, was a favorite residence of Queen Victoria (Lesley, 1976; Snowman, 1977).

Further details on the various locations see Faberge Research Newsletter, Spring and Summer 2017

The egg retains its original velvet case.

The egg was among those taken from the Imperial palaces in 1917. A note in the 1922 inventory of confiscated Imperial treasure says: “1 crystal egg with 1 emerald, containing gold folding frame.” (Fabergé, Proler, & Skurlov, Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs, London, 1997) An expert valuation was made of this egg in 1927. Found by Fabergé, Proler, & Skurlov, the valuation noted that inside the egg, a corner of the crystal above one of the miniatures was chipped off. The valuation assessed the egg’s worth at 19,082 rubles. It was the last of the five Imperial Easter eggs bought by Lillian Thomas Pratt of Fredericksburg, Virginia, and is now at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond.

On March 1-2, 2017, the UK auction house, Bulstrodes, of Christchurch, Dorset, offered as lot 650, the family Bible of the Allen family of Cathcart House, Harrogate, in England, “…including handwritten letters from Carl Fabergé, dated October, 1895, asking for images of Cathcart House to be used in the 1896 Imperial egg.”

One letter says in part ‘His Majesty the Emperor has charged me to make a rich album containing views of all the places where Her Majesty lived in her youth. Would you be kind enough to send me a photo of your house in which the Princess lived in 1894.’

The lot was consigned by a direct descendant of the Allen Family. Further details on the egg can be found here.

- March 24 (OS), 1896. Would have been presented to Alexandra Feodorovna, a gift from Nicholas II; cost 6,750 silver rubles

- April 10 (OS), 1909. Housed in Alexandra Feodorovna’s study at the Winter Palace

- September 16-20 (OS), 1917. One of forty or so eggs sent to the Armoury Palace of the Kremlin in Moscow by the Kerensky Provisional Government for safekeeping

- February-March 1922. Transferred to the Sovnarkom, the Council of People’s Commissars

- June 17, 1927. One of sixteen eggs returned by the Foreign Currency Fund of the Narkomfin (Finance Ministry) to the Armoury; given inventory no. 15746

- April 30, 1930. One of twelve eggs selected for export sale

- June 21, 1930. Transferred from the Armoury to the Antikvariat (Trade Department)

- 1930. One of ten Imperial eggs sold by the Antikvariat, Moscow, to Hammer Galleries, New York, for 8,000 rubles (ca. $4,000)

- November 1939. Advertised by Hammer Galleries for $55,000

- April 1943. Displayed in Hammer Galleries, New York

- ca. 1945. Bought by Lillian Thomas Pratt, wife of General Motors executive, Fredericksburg, Virginia

- July 21, 1947. In Collection of the late Lillian Thomas Pratt, willed to Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond

CLICK THESE IMAGES FOR LARGER VIEWS

1897 Mauve Egg Surprise (3 1/4 in., 8.3 cm.)

(Forbes, Christopher, and Robyn Tromeur-Brenner,

Fabergé: The Forbes Collection, 1999, 42-45)

1896 Fabergé Miniature (4 1/2 in., 11.5 cm.) in a 1997

Stockholm Exhibition

(Welander-Berggren, Elsebeth, Carl Fabergé: Goldsmith to the Tsar,

1997, 161, Photographs © Erik Cornelius, Nationalmuseum Stockholm)

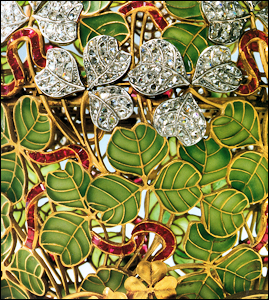

The surprise was a heart-shaped frame. There is a strong suggestion that it may be the heart-shaped frame of strawberry enamel on a guilloché field formerly in the Forbes Magazine Collection and now in Viktor Vekselberg’s Link of Times Collection located in the Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg. It is set with the date 1897 in rose-cut diamonds and opens as a three-leaf clover with each leaf holding a rose diamond-encircled photograph: Nicholas II, Alexandra Feodorovna, and their firstborn, Grand Duchess Olga. The stem is of opaque, white enamel laurel leaves, and the base is of strawberry enamel, with circles of rose-cut diamonds and decorated with pearls. A spring mechanism in the shaft is triggered by pushing the central pearl in the base, which causes the trefoil of miniatures to snap shut, leaving only the heart displayed.

It is difficult to believe that Fabergé would have ignored such a major event as the arrival of the firstborn child of a ruling Tsar, with its implications for the Romanov dynasty and the nation as a whole. The Imperial family was no doubt hoping for a boy, following Tsar Paul’s edict after the death of his mother, Catherine the Great, that no female could in future inherit the throne. While probably personally disappointed the child was a girl, the Imperial family nevertheless rejoiced in her safe arrival on November 3, 1895 (OS). The Tsar recorded in his diary: “At exactly 9 we heard a child’s squeak, and we all breathed freely! A daughter sent by God, in prayer we named her Olga.” Seventeen months later, on March 7 (OS), 1897, the Dowager Empress Marie wrote to her father, King Christian IX: “Nicky’s [daughter] is an exceptionally large baby, unbelievably sturdy and fat and so heavy that one can really hardly carry her.”

Fabergé, Proler, & Skurlov in Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs (London, 1997) correct the amount paid by the Tsar for this egg from 3,500 silver rubles to 3,250 silver rubles. There is no mention of this egg in either the 1917 or 1922 inventories of confiscated Imperial treasure. This suggests the egg had been removed before 1917, perhaps by Marie Feodorovna herself, or, if displayed in the Gatchina Palace, destroyed by vandals.

There is a possibility this may be the “Easter Egg; miniature of the Empress Alexandra and the Grand Duchess Olga inserted. Lent by H.I.H. the Grand Duchess Xenia of Russia, Windsor (Editor’s note: Xenia was a sister of Tsar Nicholas II).” This brief description appears for item no. 563 in the catalog of the Exhibition of Russian Art at Belgrave Square in London in June 1935. The description does not mention the third miniature, namely, Nicholas II, and the Olga mentioned could be Xenia’s sister Olga Alexandrovna, not her niece. The egg is included under the exhibition heading: “Ornaments by Fabergé.”

Fabergé researcher Annemiek Wintraecken in the article, “1897 Mauve Egg Surprise” in the Fabergé Research Newsletter, Summer 2014, questions the long-held belief that the frame (first two illustrations above) is indeed the surprise for the 1897 Mauve Egg. She “wonders if the strawberry red or scarlet color of the frame really blends with the mauve enamel Egg description, and if the suggested surprise frame is indeed part of the lost egg”, and even more puzzling is, “Would Fabergé have repeated a similar design concept in a smaller version (last two illustrations above) for the Mauve Egg presented to the Empress in 1897?”

- April 13 (OS), 1897. Would have been presented to Marie Feodorovna, a gift from Nicholas II; cost 3,250 silver rubles, possibly sold to a UK buyer

- 2015. Whereabouts unknown

Possible Heart Surprise

- 1962. Lady Lydia Deterding, Paris

- April 26, 1978. Lot 381 sold by Christie’s Geneva to the Forbes Magazine Collection, New York, for SFr 40,000; £11,019

- February 2004. Sold privately as part of the Forbes Magazine Collection, New York, to Viktor Vekselberg, Moscow, for an undisclosed sum

- 2015. Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

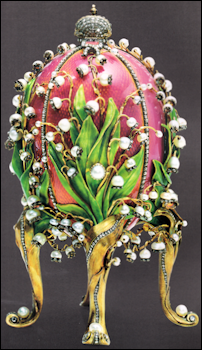

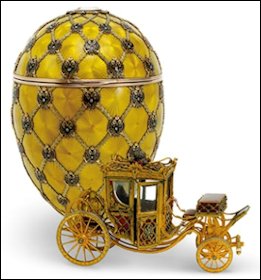

(Courtesy Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia)

The surprise concealed inside this elaborate shell is an exact replica of the Imperial coach used to carry Alexandra Feodorovna to her coronation in Moscow on May 26 (OS),1896. In yellow gold and translucent strawberry-colored enamel, the coach, one of the most splendid achievements of the goldsmith’s art, is surmounted by the Imperial crown in rose-cut diamonds and six double-headed eagles on the roof; it is fitted with engraved rock crystal windows and platinum tires and is decorated with a diamond-set trellis in gold and an Imperial eagle in diamonds on either door. It is perfectly articulated in all its parts, even to the two steps that may be let down when the doors are opened, and the whole chassis is correctly slung. The interior is enameled with pale blue curtains behind the upholstered seats and footstool, and has a daintily painted ceiling with a turquoise-blue sconce and hook set in the center. The hook may have once held a tiny egg-shaped, briolette-cut emerald pendant, which is now missing. The meticulous chasing of this astonishing piece was carried out with the naked eye without even the aid of a loupe. The yellow and black shell of the egg is a reference to the sumptuous Cloth of Gold robe worn by the tsarina at her coronation. The date is inscribed beneath a smaller portrait diamond at the bottom of the egg (Snowman, 1977).

A 1909 inventory of items in the Imperial family’s apartments at the Winter Palace adds that the egg was supported on a silver gilt stand. The inventory says the pendant was a briolette-cut yellow diamond. It also says the coach was housed separately “on a rectangular jadeite pediment with a silver-gilt rim and is contained in a glass case with silver-gilt edging. Silver-gilt Imperial crowns are placed at each of the four corners of the case. (Fabergé, Proler, & Skurlov, Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs, London, 1997) This case is visible in photographs taken of the Fabergé Tsar Imperial eggs display at the von Dervis Mansion charity exhibition in St. Petersburg in 1902. Fabergé’s invoice does not mention the tiny diamond pendant, but it does list an “emerald pendant egg with diamonds” costing 1,000 rubles. This may have been a separate gift. The invoice also lists the “beveled glass case with jadeite stand,” which was obviously meant to show off the coronation coach. The cost, 150 rubles, should be included in the total cost of this Imperial Easter gift.

The miniature coach exactly replicates the original, built in St. Petersburg by Johann K. Buckendahl in 1793, which carried the new tsarina to her coronation. The coach is extant today, having undergone no fewer than five restorations, the latest in 1992-3. Indeed, images of the Fabergé miniature coach were used as a reference point in the most recent restoration. A. Kenneth Snowman (Fabergé: 1846-1920, London, 1977) provides an intimate profile of one of the men who worked on this Easter gift:

Stein told Snowman the cost of the miniature coach alone would have been 2250 rubles – half the amount Fabergé charged the Tsar. In conversation with Snowman, Stein also said that he used the money he received for making the miniature coach to buy a far less grand form of transport-a bicycle!

The 1922 inventory of confiscated Imperial treasure indicates that a “pear-shaped diamond” was still with the Coronation Egg at that time.

- April 13 (OS), 1897. Would have been presented to Alexandra Feodorovna, a gift from Nicholas II; cost 5,650 silver rubles (included the cost for a display case billed at 150 silver rubles)

- April 10 (OS), 1909. Housed in Alexandra Feodorovna’s study at the Winter Palace

- September 16-20 (OS), 1917. One of forty or so eggs sent to the Armoury Palace of the Kremlin in Moscow by the Kerensky Provisional Government for safekeeping

- February-March 1922. Transferred to the Sovnarkom, the Council of People’s Commissars

- ca. 1925. Transferred to the Antikvariat

- ca. 1927. One of nine Imperial eggs sold by the Antikvariat, Moscow, to Emanuel Snowman of Wartski

- 1934. Transferred from Wartski, Llandudno, Wales, to Wartski, London, having been purchased for £600.

- May 19, 1934. Bought by Charles Parsons, London for £1,500

- Before June 8, 1935. Sold back to Wartski, London, by Charles Parsons

- June 8, 1935. Sold to Arthur E. Bradshaw, London, for £1,900

- 1939. Sold back to Wartski after Bradshaw’s death

- March 29, 1979. Sold by Wartski to Forbes Magazine Collection, New York for £532,000

- February 2004. Sold privately as part of the Forbes Magazine Collection, New York, to Viktor Vekselberg, Moscow, for just over $100 million, according to the purchaser

- November 19, 2013. Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond. Bequest of Lillian Thomas Pratt.

(Photo by Katherine Wetzel © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts)

Painted by court miniaturist Johannes Zehngraf (1857-1908) on ovals of ivory, each scene is carefully graded in size to match the diminishing size of the panels. In the center between the fourth and fifth panels, a gold oval pond acts as an easel and supports the pelican. It is decorated with engraved symbols of science and the arts. On the back of the second to seventh panels are listed the institutions portrayed, the second and seventh panels listing two, the remainder, one each. The enameled pelican is not an integral part of the egg but has been attached to its support as an afterthought, to reinforce the engraved symbolism and the text. When closed, the panels fit so well together that the surprise miniatures are effectively concealed. The egg is supported on a varicolored gold, four-legged stand, decorated with crowned heads of eagles, crossed arrows, and other classical ornaments (Snowman, 1962; Lesley, 1976). There was much confusion over these buildings, finally settled by the painstaking research of Fabergé sleuth, Annemiek Wintraecken.

The first pictorial miniature is of the Elisabeth Institute, founded in St. Petersburg in 1808, and is engraved in Cyrillic: Elisabeth Inst. in SPB (St. Petersburg) founded in the year 1808. The engraving is on the back of the second miniature since the first miniature itself is not engraved, because the first and last gold ovals form the front and back of the closed Egg. The St. Petersburg Elisabeth Institute was initially founded by the wife of a Colonel Gavrilov as the ‘House of Diligence’ for girls – orphaned daughters of junior officers. It was handed over to the Imperial Philanthropic Society, under the custody of Empress Elisabeth Alexeievna (1779-1826) in December 1808. The Institute was informally named after Elisabeth Alexeievna, and later, after her death in 1826, it was formally named in her honor.

The second pictorial miniature is of the St. Petersburg Nicholas Institute founded in 1837, and is engraved in Cyrillic: St. Petersburg Orphanage Nikolaevski Inst. founded in 1837. Tsar Nicholas I in 1834 had ordered the construction of the St. Petersburg Orphanage (a branch of the Moscow Orphanage) on the Moika river embankment in the former palace of Count K.G. Razumovsky. The building opened in 1837, and in 1856 after the death of Nicholas I (1796-1855), the institute was given the name Nicholas. Today the building is used by the Herzen State Pedagogical University of Russia (РГПУ), one of the largest universities in Russia, which operates 20 faculties and more than 100 departments. Significantly, the university entrance building has, as its historical emblem, the Pelican Feeding its Young. This image has an immediate and personal connection with Marie Feodorovna, wife of Alexander III

The third pictorial image is of the St. Petersburg Catherine Institute founded in 1798 and is engraved in Cyrillic: Catherine Institute founded in 1798. Wintraecken advises a two-story building known as the Italian Palace was built on a piece of land given by Peter the Great to his daughter Anna in 1711. After Anna’s death the building was demolished and a new palace was erected under the supervision of the Italian architect Giacomo Quarenghi, Catherine the Great’s court architect. He had also been responsible for the Smolny Institute. Empress Marie Feodorovna (wife of Paul I) in 1798 founded a school for girls in the new palace, the St. Catherine Institute. The institute was named after St. Catherine the Great Martyr, also known as St. Catherine of Alexandria. In 2010, the building was being used by the Russian National Library.

The fourth pictorial image is of the St. Petersburg Pavlovski Institute is engraved in Cyrillic: Pavlovski Institute founded in 1798. The Pavlovski Institute was built in the year of its founding by decree of Paul I as a military orphanage for children of officers and soldiers who died in battle. The focus was on the education of boys, and a division for girls was only supplementary. When Alexander I came to power, he ordered separate wards. In September 1806, a girls’ division was opened and renamed the Pavlovski Women’s Institute in 1829. The military orphanage at the same time was renamed for the Pavlovski Cadet Corps. In 1829, the College was taken into The Office of Institutions of Empress Marie, receiving a new status and became known as the Pavlovski Institute for ‘nobles’ (the daughters of nobility, staff and senior officers) and ‘soldiers’ (the daughters of the lower ranks and non-commissioned officers). The students lived in separate quarters, ate in different dining rooms, walked separately, and attended church at different times. The building depicted on the miniature was built in the 1840’s. In 1918 the Institute was reorganized into a unified labor school, used as a hospital during the Great Patriotic War (1940-1945), and later returned to a school again. Today it is part of the Herzen State Pedagogical University of Russia.

The fifth pictorial image is engraved in Cyrillic: Smolny Institute founded in 1764. Wintraecken reports the Smolny Institute is the large building on the right of the image. In the background is the church of the Smolny Convent. Empress Elizabeth I (1709-1762), daughter of Peter the Great, ordered her favorite court architect, Bartolomeo Rastrelli, to build a convent where she wished to spend the rest of her days. Russian tradition required that churches and cathedrals be erected on a riverbank, so Rastrelli chose to place the convent in a bend of the Neva River previously allotted for the Smolnoi dvor (the tar-yard for the needs of the Admiralty). The convent’s official name was the Resurrection Novodevichy Convent, but it was known as the Smolny Convent among the citizens, since ‘tar’ is ‘smola’ in Russian. The construction of the Convent began in 1748 and continued for an extended period. Empress Elizabeth did not live to see it completed.

Catherine II in 1764 opened a boarding school for ladies on land of the Smolny Convent. The school became known as the Smolny Boarding School for Young Ladies of Noble Birth, an educational establishment for the elite. After Catherine’s death in 1796, Empress Marie Feodorovna (wife of Paul I) took over the institute and made changes that set the Smolny’s course for the rest of its existence. Throughout the 19th century, the Smolny maintained its reputation as the most elite educational institution for girls and was regarded as synonymous with high cultural standards, manners, and poise. The many references to Smolny in the Russian literature of the 18th and 19th centuries attest to the school’s cultural significance. In October 1917, Vladimir Lenin and the Bolsheviks appropriated the Smolny Institute and made it their headquarters until March 1918. Since then, the Smolny campus has continued to be used for government purposes, eventually becoming home to the St. Petersburg Duma. Several rooms have been preserved as a museum honoring the Institute’s past.

The sixth pictorial image is engraved in Cyrillic: Patriotic Institute founded in 1827. In the 18th century a wooden structure on Vasilevski Island was purchased for the Women’s Patriotic Society. In this building in 1812, a school was established for girls (daughters of officers), whose fathers had been killed during the Napoleonic war. In 1827, the school received the status of institute and in 1828 it was rebuilt with two side wings. In the years 1831-1834, the Russian writer Nikolai Gogol, now considered the father of modern Russian realism, worked there as a teacher of history. After the 1917 Revolution, the buildings of the Patriotic Institute were handed over to the Women’s Polytechnic Institute, later named the Second Polytechnic. The building today houses the Energy College (Power Engineering College) of the State University – Higher School of Economics.