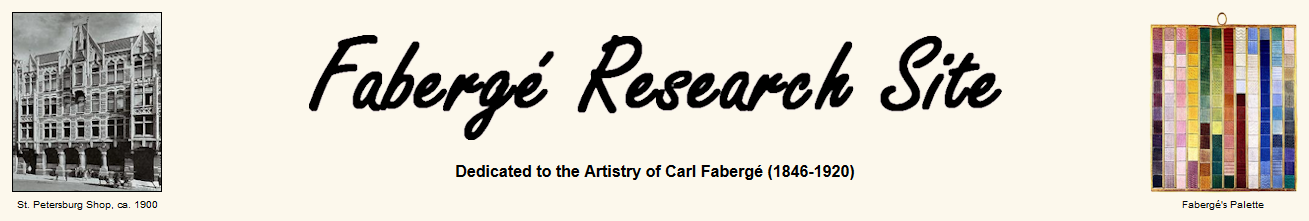

Fersman Portfolio

(Courtesy Christie’s)

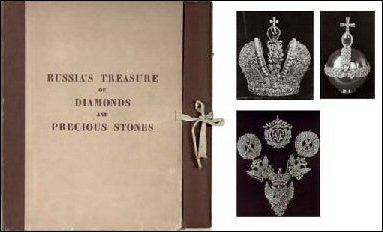

Fersman Portfolio, Fabergé Plastron

by Oscar Pihl

(Courtesy Heritage Auctions)

1985 Remade Plastron

(Nicholson, Jewels of the Romanovs,

1997, 56)

After the 1917 October Revolution, the Romanov jewels became the property of the people and the fledgling Soviet government. The latter, desperate for foreign currency and equipment (such as plows and tractors), in order to rebuild its country after World War I began the sale of the crown jewels, and eventually, large amounts of Russian decorative and fine art objects.

The political turmoil surrounding these Soviet sales from 1918-1938 are discussed in three very recent publications:

Bayer, Waltraud, ed. Verkaufte Kultur: Die Sowjetischen Kunst- und Antiquitätenexporte, 1919-1938 (Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2001). In German.

Odom, Anne and Wendy R. Salmond, eds. Treasures into Tractors: The Selling of Russia’s Cultural Heritage, 1918-1938 (Washington, DC: Hillwood Estate, Museums & Gardens, 2009).

Agathon Fabergé, Nuptial Crown and Other Russian Crown Jewels, 1923

(Fabergé, Proler, and Skurlov, The Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs, 1997, 66)

Russian Crown Jewels Newsreel

(Courtesy British Pathe)

The New York Times (February 26, 1926, 2) announced the publication of the set:

All of the glories of the Romanoff crown jewels, compromising 496 (correct number is 406) separate objects, have been recorded in four elaborate volumes published today by the jewel department of the Soviet Government … issued in four languages, Russian, English, French and German under the editorship of Professor A. E. Fersman, an eminent Russian gemologist, and S.M. Troynitsky (Director of the Hermitage Museum) of Leningrad. Government authorities say the purpose of these books is

- To repudiate the rumors abroad that the crown jewels have been sold or broken up,

- To make a contribution to the Science and History of Mineralogy,

- To leave for future generations of Russians an accurate and authentic description of the gems which the Government expects soon to convert into cash, and

- To acquaint intending foreign purchasers with the details of the collection, which is described as the greatest aggregation of regal jewels in all history.

Norman Weisz (d. 1963), a Hungarian-born jewelry merchant trading in London, is described as a ‘colorful character’. The Australian press (Poverty Bay Herald, Gisborne, New Zealand, October 19, 1920, 5) writing about him mentions his affluent wealth and lifestyle, a turf fraud case in the British court system, and calls him a ‘fashionable conspirator’. The obituary of Weisz in the Singapore Strait Times (Reuters News, July 19, 1963) states he ‘bought the Czarist crown jewels for £1 million … he came with 3s 6d in his pocket’, got a job, served in World War I, went to Russia with a letter of credit, and bought the court treasures.

In a review of The Times (London) his name appears again and again in connection with legal issues. By 1920, he had served a prison sentence of 15 months for a racehorse fraud. His sins – he entered a race for a horse which did not exist, and he disguised a previously successful race horse by painting it in a different color, then entering it under a false name in a novice race and netting at least £3000. His defense cost £10,000. From 1925-27, he was involved in buying Russian crown jewels and consigned 124 lots from the Soviet purchase to a Christie’s auction which realized £80,561. The proceeds went toward the dissolution of a partnership. Weisz may have been involved with Michel Norman of the Paris-based Australian Pearl Company in buying the Diamond Trellis Egg (made by Fabergé in 1892) from the Antikvariat (Trade Department of the Soviet government). In 1929, he was entangled as an unwilling party to a London court case brought by the Russian émigré, Princess Olga Paley. She argued Weisz was buying property amounting to $240,000 offered by people who did not own it, i.e., the Soviet government. Weisz won the case.

To paint the mood in London, we cite an article published in The Evening Post, March 16, 1927, 11:

At this Christie’s London sale, Magnificent Jewellery … Part of the Russian State Jewels, The Nuptial Crown (lot 62) with a simple four line description sold for £6,100 to Founés (possibly antiques dealer Isaac Founés, one of the most important dealers in French furniture of his time). The bidding started at £5,000.

The nuptial crown worn by Tsarina Alexandra when she married Tsar Nicholas II on November 26, 1894, is perhaps the most easily recognized object from the Russian crown jewels sold in the West.

Nuptial Crown, Fersman Portfolio, ca. 1922

(Courtesy Heritage Auction Galleries)

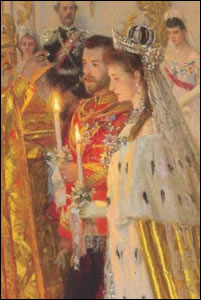

1894 Wedding of Nicholas II and

Alexandra Feodorovna

(Courtesy The Royal Collection)

1866

Tsarevna Marie

Feodorovna

1874

GD Maria

Alexandrovna

1884

GD Elisabeth

Feodorovna

1884

GD Elizaveta

Mavrikievna

July 1894

GD Xenia

Alexandrovna

Nov. 1894

Alexandra

Feodorovna

1902

GD Elena

Vladimirovna

1908

GD Maria

Pavlovna

In 1894, Alexandra Feodorovna wore the crown for her wedding to Tsar Nicholas II, shown in a painting by Lauritz Tuxen. The painting was commissioned by Queen Victoria who was Alexandra’s grandmother. After the Tsarina, the crown was worn in 1902 by Grand Duchess Elena Vladimirovna at her wedding to Prince Nicholas of Greece, and in 1908, for the very last time, by Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna (the younger) at her wedding to Prince Wilhelm of Sweden and Norway. (Images Courtesy State Hermitage Museum, The Royal Collection of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, and Alexander Palace Forum)

In less glamorous times the journey of the nuptial crown from the 1927 London auction to the 1966 New York auction must surely involve both jewelers and owners – as yet unknown – on both sides of the Atlantic ocean. In the 1930’s the crown was seen by Prince Christopher of Greece and Denmark at Cartier in New York, and then it was sold from the estate of Helen de Kay of New York in 1966. Its journey after this time is well documented – Harry Levinson, A La Vieille Russie on behalf of Marjorie Merriweather Post, and from July 5, 1977, on public view at the Hillwood Estate, Museum and Gardens in Washington (DC).

Helen de Kay (incorrectly cited as deKay), the widow of Sidney Gilder de Kay, vice president, director and general legal counsel of Olin Industries, manufacturers of rifles, shotguns, ammunition, skeet equipment, survived her husband by seventeen years. She was a collector of many interests – jewels, paintings, valuable Chinese jade, coral, carvings and furniture for her two residences in New York City and Greenwich (CT). Her small Fabergé collection of seven pieces was part of a four-day estate sale at Parke-Bernet in early December 1966. The December 7th jewelry sale which included the nuptial crown and a golden chalice realized $1,115,585. Both objects are now in the Marjorie Merriweather Post Collection, Hillwood Estate, Museum and Gardens, Washington (DC). Her articulated female figure of a bowenite magot (female goddess of happiness and good fortune) by Fabergé sold for $35,000 on December 9, 1966. Current whereabouts unknown.

The New York Times (December 8, 1966) reviewing the sale states, ‘A flurry of bids brought the price of the bejeweled crown from $15,000 to about $50,000 and then Harry Levinson and A La Vieille Russie of New York fought it out. Mr. Levinson won’.

Mr. Harry Levinson, of Levinson’s Jewels, Chicago, Illinois

(Photo Corbis Images)

One final stop on our journey was to find out how many of the 350 printed copies of the Fersman catalogs still exist. Ten English language editions are in American libraries, and one each in Berlin and Munich. Two copies in French with the title, Les Joyaux du Trésor de Russie, are in a British private collection and a Paris library. The authors are not aware of any German editions. Auction records reveal four English copies have come under the hammer:

2000-01 Sotheby’s London sold two copies for $21,084 and $45, 992, inclusive of the buyers’ premiums.

2007 A copy with an Ex Libris Umberto, Prince of Piedmont, later King Umberto II of Italy sold at Christie’s London for $141,984.

Two French editions have sold at Christie’s – in 2008 in Geneva a copy signed by Alexander E. Fersman realized $71,861, and in London in 2010 a copy realized $64,230.

Kudos: Our thanks to Dr. Smylie of Heritage Auction Galleries, Marie Betteley, Geoffrey Munn of Wartski, and our librarian friends who always turn up treasures in books – Lois White (Getty Research Library), Rose Tozer (Liddicoat Library, Gemological Institute of America), Pam Payne (Huntsville Public Library), and Anne Coleman (Salmon Library, University of Alabama in Huntsville).

Russian Art

Highlights from the sale included a Fabergé silver and bowenite Japonisme-inspired table lamp with a Nobel family provenance (achieved £193,250 with an estimate £80,000 – 120,000), and a Fabergé hardstone model of a turkey (£193,250, est. of £60,000 – 80,000). A Fabergé bonbonnière with a scratched inventory number 22267, similar to Wigström sketches, realized £115,250 (est. £20,000 – 30,000). According to Christie’s, the sale results for the Fabergé items were 97% by value and 95% sold by lot, and this maintained Christie’s 53% of the total Fabergé market share. (Information courtesy of Helen Culver Smith, Christie’s)

Fabergé Turkey

(Courtesy Christie’s)

Denissov-Uralski Turkey

(Muntian, Fabergé: Juwelier

van de Romanovs, 2005, 119)

Born in 1864, Alexei Kuzmich Denissov (he added Uralski to his name to reflect the region from which he came) received his diploma of master in sculpture from the Ekatarinenburg guild of sculptors in 1884 and exhibited his works in Scandinavia, Paris, Reims (where he obtained a Gold Medal in 1903), and in St. Louis (where he was awarded a Silver Medal in 1904). He established himself in St. Petersburg first at Moika Street 42 and became Fabergé’s neighbor on Bolshaya Morskaya Street between 1910 and 1913.

In 1911/12 the jeweler Cartier acquired an impressive total of 62 animal figures from Denissov-Uralski. The acquisitions included an obsidian owl which is illustrated as a pencil drawing in the margin of the French firm’s acquisition ledgers. It is virtually identical to an owl in the Lillian Thomas Pratt Collection at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. The latter, however, despite its original fitted case stamped Fabergé, was apparently also an acquisition from Denissov-Uralski. It is known from contemporary sources that Fabergé’s in-house stone-carving workshop, founded in 1908, was swamped with orders, and was barely able to keep up with the incoming commissions. What may have been more logical than to turn to his celebrated neighbor for help?

November 11, 2010 Auktionshaus Dr. Fischer, Heilbronn, Germany

Russian Art, Fabergé and Icons includes a Fabergé glass and silver inkwell stand.

November 29, 2010 Christie’s, London

Russian Art

November 2010 Olivier Coutau-Begarie, Paris

Russian Art

December 1, 2010 Sotheby’s, London

Russian Works of Art, Fabergé & Icons

(Updates are posted in Exhibitions on the Fabergé Research Site)

A La Vieille Russie à Paris: Fabergé et la Russie impériale au carrefour des cultures

Box with Portrait of Catherine the Great and Violet by Fabergé

(Courtesy A La Vieille Russie)

September 18 – October 10, 2010 Russian Ambassador’s Residence, Hôtel d’Estrées, Paris

Arts et Traditions en Russie, de Pierre le Grand à Nicolas II

Exhibition is part of a Russia in France celebration year. Selected Fabergé items from this exhibition will be in a November auction at Olivier Coutau-Begarie. Contact.

November 23 – December 3, 2010 Wartski London

The Last Flowering of Court Art

Typical Russian Pilgrim

(Courtesy Christie’s)

Siberian Hardstones Bogomoletz

(Courtesy Wartski)

Spring 2011 A brief announcement in the Swiss Basler Zeitung (June 13, 2010) suggests a possible exhibition of “The Link of Times” Collection (the former Forbes Magazine Collection and now owned by Viktor Vekselberg) may be in the planning stage.

The Dowager Empress and Grand Duke Nicholas Nicholaievich, Jr.,

Departing Yalta Onboard the HMS Marlborough on 8 April, 1919.

(Courtesy Royal Russia)

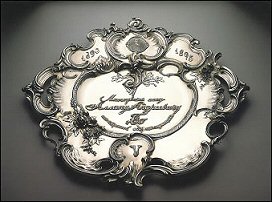

Fabergé Bowl Presented to Allan Bowe in 1895 Honoring His Service to the Firm

(Bowl Photograph Courtesy Forbes Magazine Collection)

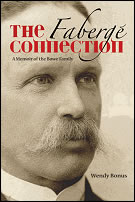

The author is a great grand-daughter of Henry Allan Talbot Bowe, business partner of Carl Fabergé from 1887 to 1906. Using family diaries from Bowe’s daughter Essie and standard Fabergé books, Ms. Bonus has written her family’s history. During Bowe’s tenure with the House of Fabergé the Moscow and Kiev branches were opened. His brother Arthur opened and managed the London branch beginning in 1903.

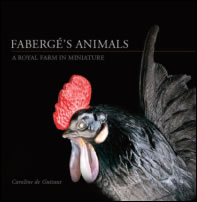

Fabergé Animals:

A Royal Farm in Miniature

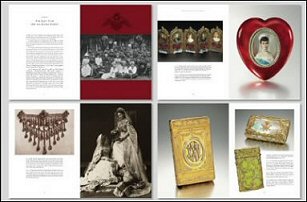

Jewels of the Romanovs: Family & Court

- Symbolism of the Pelican Egg

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond Bequest of Lillian Thomas Pratt.

(Photo by Katherine Wetzel Virginia Museum of Fine Arts)

- Photo Identification

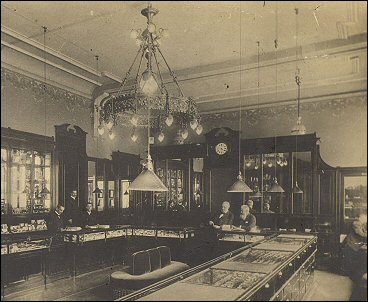

Fabergé Shop in St. Petersburg

(Courtesy Wartski)

- Update on Queen Victoria Jubilee Brooch (Fabergé Research Newsletter, Summer 2010) The Times (London), October 18, 1897, 8A, in the article, The Queen’s Jubilee Presents and Addresses, mentions among the gifts from “… the family of Princess Alice, including the Emperor and Empress of Russia … a brooch of diamonds and of beautiful cabochon sapphires”.

- Is anyone aware of a set of flatware in the King’s pattern marked Fabergé?

- The newsletter editors are frequently asked about Fabergé cigarette cases. Have any studies been done on this topic other than the 1998 publication on the Traina Collection of cigarette cases?

- A reader is interested in identifying the monogram on the cigarette case shown below.

Silver Art Nouveau Case

- Searching for a series of miniature portraits of Tsar Alexander III, probably rectangular or square, possibly similar to the miniatures of the 1890 Danish Palaces Egg. The miniatures with the Danish palaces and yachts, as well as other Russian jewels, can be seen in a 1933 newsreel.

Jewels!

(Courtesy British Pathe)