Newsletter 2017 Spring and Summer

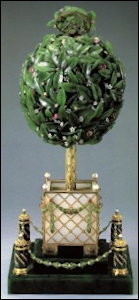

1898 Lilies of the Valley Egg

(Courtesy Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia)

This issue of the newsletter reveals a variety of new facts about Fabergé eggs made over 100 years ago!

Also completed are the Fabergé Imperial Egg Chronology of 52 Tsar Imperial eggs thanks to the efforts of Will Lowes, Adelaide, Australia, and a new mobile friendly look for our website thanks to Ben Swindle at Ben’s Computer Services, Falkville, Alabama.

Feature Stories:

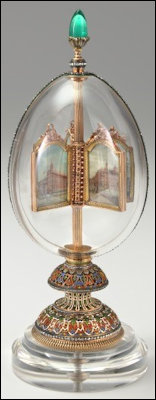

- Egg with Revolving Miniatures in the Pratt Collection, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts: The Puzzle Completed

- Personal Messages on the Zehngraf Miniatures: 1896 Egg with Revolving Miniatures

- Egg News: 1894 Renaissance Egg (Fabergé and the Green Vault in Dresden), 1900 Paris Exposition Universelle, 1906 Swan Egg, 1907 Yusupov Egg, 1911 Orange or Bay Tree Egg, 1902 von Derwies Vitrines, Filming Fabergé Eggs

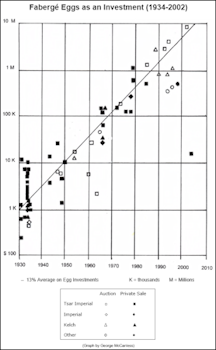

- Fabergé Eggs as an Investment: A Statistical Analysis

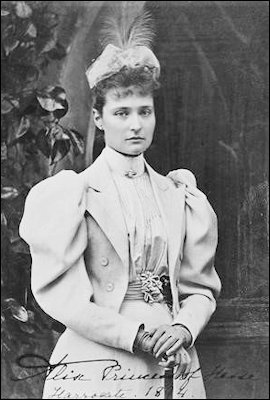

Postcard signed in pen, Alix Princess of Hesse. Harrogate. 1894.

1896 Tsar Imperial Egg depicts Alexandra’s path in miniatures from childhood to Russian Empress. The iconic decoration of the egg’s stand elucidates this transition

from the monogram and crown as Alix, Princess of Hesse and by Rhine on the upper register to the base itself with her imperial cipher as Empress Alexandra Feodorovna.

(Postcard; Photographs: Katherine Wetzel © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts)

A chronological summary relating to the miniatures was compiled by Courtney Tkacz, archivist, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (VMFA) and Christel McCanless, and is further updated with primary source materials from correspondence, diaries and memoirs gathered by independent researcher DeeAnn Hoff in the collage below entitled, “Personal Messages on the Zehngraf Miniatures”:

- 1945 9 sites are identified on the original Hammer Galleries invoice with these descriptions:

Within the egg, twelve hand-painted miniatures on ivory, signed, by Zehngraf. Framed in gold and controlled by the emerald at the apex, revolve on a gold columnar Axis. These, of the royal residences in Germany, England, and Russia associated with the Life of the Tsarina, include views of palaces in and near Darmstadt, Hesse, such as the Neue Palais at Darmstadt and Kranichstein in Hesse; Rosenau, Coburg; Balmoral and Windsor Castles and Osborne House in the British Isles; the Winter, Anitchkov and Aleksandr Palaces of Russia. (Courtesy of Barry Shifman, VMFA Sydney and Frances Lewis Family Curator – Decorative Arts from 1890 to the Present, from the museum’s curatorial files)

- 1960 First published VMFA catalog written by Parker Lesley identified 10 sites.

- 1986 Fabergé enthusiast George Terrell assisted VMFA in verifying locations. (The 8 1/2×11” black and white photographs are still in the McCanless archives, when I was a newbie to this Fabergé addiction, and of no help at all!)

- 1990’s Independent researcher Marilyn Swezey wrote to the museum identifying the last two sites (not confirmed with archival photos).

- 1995 VMFA catalog published for the first traveling exhibition of the Pratt Collection written by David Park Curry identified all 12 sites.

- 2015 Tatiana A. Tutova, who works in the Moscow Kremlin Museum’s Archives, published her research about the 1896 egg and other Fabergé eggs in her book entitled, The Fate of Palace Treasures of the Russian Imperial Court. The Inventories of a 1922 Special Commission in the Moscow Kremlin. Her specific findings on the 1896 egg are included in a collage of Russian Fabergé egg photographs taken in the 1930’s.

2016-2017

- Mark Miller, director of the Museum Schloss Fasanerie, found an archival postcard for the Veste Coburg. Shifman suggested a reader’s challenge to find another missing location be published in the Fabergé Research Newsletter, Summer 2016.

- Two astute newsletters readers published their findings on the Harrogate, UK, mystery – Ursula Butschal, editor publisher of Royal Magazin, and Annemiek Wintraecken, webmaster of Mieks Fabergé Eggs. Along with other historical details Wintraecken discovered a postcard signed Alix Princess of Hesse. Harrogate. 1894 (illus. left above). In February 2017, Elizabeth Jane Timms, a brand-new newsletter reader, advised the portrait postcard is a part of a larger photograph taken in Coburg on the day the future Emperor Nicholas II and his bride, Princess Alix of Hesse, later Empress Alexandrovna, became engaged.

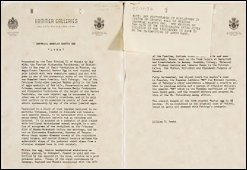

- Tkacz and Shifman reviewed documents in the VMFA’s curatorial files. They shared their detective work:

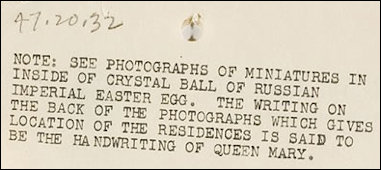

Shifman found the photographs referenced in the typewritten note attached to a Hammer Galleries egg description. There are four of them, depicting eight of the miniatures, and five of them are identified on the back in the same cursive handwriting. We located several of Queen Mary’s letters on Google and after comparing the two, while similar, we do not feel that they are the same handwriting.

- In the News & Notes column in the VMFA, Winter/Spring 2017 issue (published for museum members) the new research about the fifth and last egg acquired by Mrs. Lillian Thomas Pratt and willed to the museum in 1947 is summarized. The article is reproduced in full courtesy of Ursula Butschal, Royal Magazin. Based on newer information, the statement “of her in front of the house” should instead refer to the engagement photo discussed above. More detail on Mieks Fabergé Eggs.

- DeeAnn Hoff, independent researcher and history buff, challenged herself to find primary source material (correspondence, diaries, memoirs, etc.) for each of the 12 Zehngraf miniatures to update assumptions suggesting why the landmark locations were selected for the 1896 Easter gift to Empress Alexandra. Shifman spearheading this research journey for the better part of a year, and his colleague, Howell Perkins, Coordinator of Imaging Resources, generously shared VMFA’s existing collage of miniatures, context notes, and archival details for the Imperial Rock Crystal Egg (the egg’s alternate name, VMFA Acc. #47.20.32). Adding to the completion of the puzzle are earlier research efforts by Katrina Warne, independent researcher, and Marion Wynn, a Romanov enthusiast, who quite some time ago were intrigued with the Empress’ Harrogate connection. A copy of their publication is attached to Ms. Hoff’s findings which combined with the 1896 Revolving Egg miniatures from VMFA and archival documentation bring alive the history of this fascinating Fabergé egg.

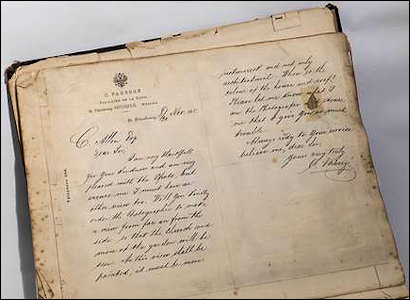

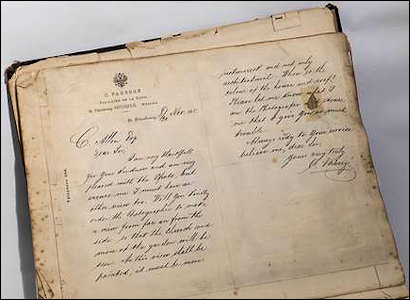

- At the Bulstrodes (Christchurch, UK) auction on March 2, 2017, the Harrogate’s Royal Pump Room Museum, acquired through the generosity of Wartski London and other donors a christening set (not by Fabergé), a scrapbook, and two letters written by Carl Fabergé. The letter below relates to the Harrogate miniature ivory painting (a mere 1 x 1/16 in., 2.5 x 2.8 cm) by Zehngraf in the 1896 Fabergé Imperial Egg at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. It confirms how the model for this miniature and possibly others were obtained over 100 years ago.

Fabergé Letter at the Buldstrodes Auction

(Courtesy the Saleroom with an Incorrect Auction Date Cited)

VMFA conservators further examined the miniatures and discerned the three miniatures that did not have ‘visible’ signatures are: Rosenau, Coburg, Congregational Church, and Cathcart House, Harrogate, UK, and Anichkov Palace, St. Petersburg. Further examination would involve opening the crystal and then removing the miniatures from their metal frames; this was not recommended due to ‘safety concerns’.

These twelve miniatures set in their gold frames, revolving around a gold shaft through the center of the egg of rock crystal, comprise the poignant ‘surprise’ within this Fabergé Imperial Egg presented to Empress Alexandra Feodorovna for Easter 1896. Literature long identified the paintings as locales dear to Alexandra during her childhood up to and including her courtship and engagement to then Tsesarevich Nicholas Alexandrovich. Since 1945 varying captions accompanied these miniature scenes in the post-Imperial publications of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts ‘Egg with Revolving Miniatures’. No narrative illuminates the deep and personal significance of the sites memorialized in the Zehngraf miniatures more intimately than the words of those who inhabited them. From that perspective, I am sharing a few passages from the genre of letters, diaries, and memoirs.

Miniature

Context

Neue Palais (New Palace) was the birth place of Princess Alix von Hesse-Darmstadt, the future empress of Russia. Darmstadt was the small capital city of the Grand Duchy of Hesse and by Rhine, and the palace, built just six years earlier, was set in a large park beside a lake.

Details

The Renaissance Egg was the last Fabergé egg presented by Alexander III to his wife Maria Feodorovna in 1894. It is generally agreed that it was inspired by an 18th century LeRoy casket in the New Green Vault. Nearly all the items on display in the New Green Vault have little cards next to them detailing the object, but there was nothing by the casket to say what it is, or that it had inspired Fabergé.

18th Century LeRoy Casket

(Photograph by the Author)

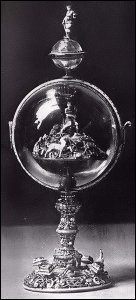

In the New Green Vault, but in a different room to the casket there is another object (illustrated left below) mentioned by A. Kenneth Snowman, which is a possible inspiration for the Resurrection Egg.

Art of Carl Fabergé, 1962, (Illustration 305, Opposite p. 80); Ca. 1560 Rock Crystal Clock Made in Dresden by Heinrich Hoffman, Now in the Historic New Vault, Dresden

(Colored Photographs by the Author)

1900 Paris Exposition Universelle

Annemiek Wintraecken has found and discusses on her website an eye-witness account of Fabergé eggs shown at this venue.

Swan Egg

The possible prototype for the surprise of the 1906 Fabergé Swan Egg (given by Nicholas II to his mother, Marie Feodorovna) traveled to the Science Museum in London. It is the “first time the swan has left the Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle, County Durham, England, since it was purchased by the founders in 1872. The life-sized artefact, which comes to life once a day, twists its head, preens, and catches a fish” was on view February 8 – March 23, 2017. (“Bowes Museum Silver Swan Flies Nest for Robot Exhibition”, BBC News, Nov. 15, 2016)

Yusupov Egg (1907) by Fabergé was on display during the International Fair of Haute Horlogerie in Geneva (January 16-20, 2017)

- Further details including a video of the event were published: “Prince Youssoupoff’s Fabergé’s Egg Is on Display”, Romanov News/Новости Романовых, January 2016 [sic, more correctly 2017], #106 published by Ludmila & Paul Kulikovsky.

- “Fabergé’s 1907 Yusupov Egg Out of the Shadows” by Paul Gilbert appeared in the author’s blog, Royal Russia News, January 18, 2017.

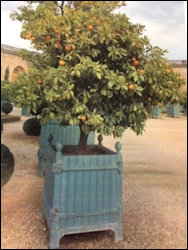

1911 Orange Tree Egg

(Courtesy Forbes Magazine Collection and Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg)

Orange Blossum

(wiki)

Orangeries, Versailles Gardens

(wiki)

2Essays relating to this topic are “1911 Bay Tree Egg – Its Antecedents” by DeeAnn Hoff, Fabergé Research Newsletter, Fall 2013; the Fabergé Imperial Egg Chronology.

2016: Vitrines (left and right only) of the Bases in the Pompeian Room, New Hermitage Museum

(Courtesy Hermitage Museum, Close-ups in this Essay by Domen Kaozan, 12-year Old Grandson of Riana Benko)

Newsletter contributor Tim Adams added from Wikipedia: “Russian Emperor Nicholas I commissioned von Klenze in 1838 to design a building for the New Hermitage, a public museum that housed the Romanov collection of antiquities, paintings, coins and medals, cameos, prints and drawings, and books.”

Benko traced the vitrines back to the mid-1850’s:

1856: Interiors of the New Hermitage, The Empress’s Cabinet, Watercolors by Edward Petrovich Hau (1807-1887)

and Vitrine in New Hermitage Museum

(Courtesy Hermitage Museum)

How and why do the vitrines made in St. Petersburg for Empress Maria Feodorovna after 1856 and the 2016 viewing by Forbes relate to the von Derwies mansion Exhibition of Objets D’Art and Miniatures, March 9-15 (O.S.), 1902?

Extant photographs of only the second public viewing of Fabergé eggs after their initial showing at the 1900 Paris Internationale Exposition were shared by Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm, Finnish author and researcher of St. Petersburg jewelers:

A.

B.

C.

-

In the middle of the von Derwies room under the chandelier is a matching tall virtine with assorted Fabergé objects. On the wall cabinet to the right is a pair of embracing amorini in the Louis XVI style1. At the back of the room a walk-thru leads to a second room with two vitrines.

-

Vitrines labeled Maria Feodorovna (first) and Alexandra Feodorovna (next) display the Fabergé eggs loaned by the two Empresses.

-

A close-up of Fabergé eggs in the AF case. Over the years various scholars have researched and identified the Fabergé eggs in the vitrines.2

D.

E. -

Pine Cone Finial; E. Decorative connections between the pieces of glass reveal a further match.

The exhibition lasting only from March 9-15, 1902, is described at length with many interesting details (objects shown, lenders, etc.) in two Russian contemporary newspapers, Novoie Vremia, St. Petersburg, March 9 and 10, 1902, issues, and Journal Niva, No. 12, 1902.3 More than 15 Fabergé eggs were exhibited in the two display cases for the Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna, and Empress Alexandra Feodorovna. The charity benefitting from the venue were the schools of the Imperial Ladies’ Patriotic Society. The Novoie Vremia article concludes, “The great success of the exhibition became evident from the first day: 3000 roubles in entrance fees were collected today. As from tomorrow and until 15 March, the entrance fee will be one rouble 10 kopecks”. The Niva article ends with these words, “This interesting and unique exhibition was unfortunately of very short duration … after less than two weeks (sic).” The text only of a 1902 advertisement for the seven-day event in two large rooms in the von Derwies Mansion is extant.4

As the details on this research began to fall into place one question remained, why use a mansion for an exhibition for seven days when presumably the mansion was the family’s home? Independent scholar Galina Korneva from St. Petersburg, Russia, answered this question with some limited known facts from Russian publications. Details found on the internet and in English publications were inconclusive. She suggests:

Actually there were two buildings on English Embankment which belonged to von Derwies family. The Palace (English Embankment contemporary address #28) and the other one (English emb. 34a and English emb. 34b were joined together under #34). Architect Krasovsky rebuilt #28 in 1889-1890. Until after the death of the Baroness, no one touched or sold the buildings in the complex, since it appears both her sons (Pavel and Sergei) preferred to live on their estates.

Korneva ends on a personal note – my sister and one of my daughters had their official weddings in this building English emb. #28, since for many years it served as the #1 palace for weddings in St. Petersburg.

2Recently the 1887 Tsar Imperial Egg was found based on the Maria Feodorovna von Derwies exhibition case, etc. Details in the Fabergé Research Newsletter, Summer 2014.

3Fabergé, Proler, and Skurlov. The Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs, 1997, Appendix 2, pp. 251-252.

4Bianchi, Fabergé, An Introduction, 2000, p. 28, published by Broughton International for the Wilmington, Delaware, Fabergé exhibition.

Emmanuel Ryz, a French film producer, delighted the attendees of the 2017 Fabergé symposium in Houston, Texas, with his video about Fabergé eggs. It was received by a hushed audience! He is extending his generous gesture to newsletter readers by introducing the intent of his future film:

Considered priceless treasures, the Fabergé eggs are now scattered throughout the world and continue to fascinate viewers. Seven Imperial eggs have disappeared and remain unaccounted for to this day. Specialists, descendants, art dealers, private collectors, Russian and Americans tycoons are still looking for these precious gems. Like them, we follow this insane quest around the world. We will go in search of the mysteries for one of the greatest treasures of mankind in St. Petersburg, London, Moscow, Geneva, Paris, Monaco, Washington, New York … and so many other locations which conserve and protect the original copies of Carl Fabergé’s work. We will circle the world, trying to retrace the journey of the Imperial Fabergé eggs! Never have 50 Imperial Fabergé Eggs been gathered in a single place. That is the ambition of our film.

The auction and private sale data for the logarithmic graph below was gathered from published sources – original invoices found by Valentin V. Skurlov in the Russian archives1, auction catalogs, and the Fabergé Imperial Egg Chronology. Financial data generously shared by Christopher “Kip” Forbes lists the amounts (below left) paid for eggs acquired by the Forbes Magazine Collection (FMC). In total, the late Malcom Forbes purchased 15 eggs of which three were not given to the two tsarinas, Marie Feodorovna and Alexandra Feodorovna. The collection grew in the 1960’s-1980’s, and by June of 1985 permanent galleries opened on the first floor of Forbes Magazine headquarters, 60 Fifth Avenue, New York. In 2004, Mr. Victor Vekselberg in a direct sale purchased nine Fabergé eggs from the Forbes Magazine Collection for an undisclosed sum. Sotheby’s New York before cancelling the auction had published an estimate of $80-$120 million for the eggs, and the rest of the Fabergé objets d’art in the same collection.2 These objects became the nucleus of what is now the Fabergé Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia.

The graph with symbols (below right) includes the four categories of eggs, the year of the sale and price realized. Data for 1929 is shown as data for 1930. The turn of events after World War I, which led to the dispersal of the Fabergé eggs from Russia to the western world, is a story full of mystery and intrigue.3 Much has been written recently about this topic since records from the Soviet times are now available in Russian archives.

- 1913 Original cost of 24,600 rubles ($299,173 in 2014 dollars)4

- 1949 $5,236 including a 10 percent buyer’s premium

- 1994 World record price of $5,587,3085

- 2002 World record price $9,579,5006

1913 Winter Egg

(Courtesy Christie’s New York)

- Well-researched and documented

- Collector provenance or confirmed historical connections

- Genuine stock number(s)

- Listed in the Fabergé London Sales Ledgers for 1907-1917

- Illustrated in the design books of the Albert Holmström8 or Henrik Wigström9 workshops

- Good condition and/or in original box

- Shown extensively at Fabergé exhibitions

- Featured piece in the auction catalog, etc.

High prices and insurance costs may discourage the building of high-end large private collections. Bidders may wish to remain anonymous, or be part of a syndicate in which the risk is spread. Expensive Fabergé objects, such as the Winter Egg, are not seen in exhibitions due to insurance and security concerns. The era of Fauxbergé10 and proliferation of modern objects made in the style of Fabergé11 require the occasional and the seasoned collector to become knowledgeable before acquiring objects for investments. However, the results of rising prices for Fabergé Easter eggs over three-fourth of a century at a compounded rate of 13% leads one to be optimistic.

The author gratefully acknowledges the assistance of Will Lowes, George McCanless, and Sheila Mikell.

2Forbes Staff, “Russian Tycoon Buys Forbes Fabergé Eggs”, April 2, 2004.

3“New Research” in Lowes and McCanless, 2001, pp. 1-16.

4Benko, Riana, “Statistical Cost Analysis of Fabergé’s 50 Imperial Easter Eggs”, Fabergé Research Newsletter, Fall 2015.

5Christie’s Geneva, November 16, 1994; Lowes and McCanless, 2001, pp. 121-124.

6Christie’s New York, April 19, 2002, includes a 19.5% of the final bid price of each lot up to and including $100,000, and 10% of the excess of the hammer price above $100,000 in Christie’s Saleroom Notice, April 19, 2002.

7For extensive details on Fabergé hallmarks, marks, and workmaster specialties. Lowes and McCanless, 2001, pp. 175-245.

8Snowman, A. Kenneth, Fabergé: Lost and Found, The Recently Discovered Jewelry Designs from the St. Petersburg Archives, 1993.

9Tillander-Godenhielm, et al. Golden Years of Fabergé: Drawings and Objects from the Wigström Workshop, 2000.

10von Habsburg, Géza, Fabergé in America, 1996, pp. 329-338; Marina Lopato, “More Fauxbergé” in von Habsburg, Fabergé: Imperial Craftsman and His World, 2000, pp. 386-388. Steve Kirsch Fauxberge website.

11Reproductions of the original objects of inferior quality and false marks are available worldwide. Caveat emptor!

(Updates are posted in Exhibitions on the Fabergé Research Site)

Fabergé: Royal Gifts Featuring the Trellis Egg Surprise exhibition highlights the reunion after more than 80 years of the 1892 Diamond Trellis Egg given at Easter by Emperor Alexander III to his wife Maria Feodorovna with the original elephant surprise, a jeweled automaton discovered in 2015 in the British Royal Collection Trust. The elephant will be on view until April 1, 2018.

1892 Diamond Trellis Egg by Fabergé and Elephant Surprise

(Courtesy Dorothy and Artie McFerrin Collection and Royal Collection Trust)

Fabergé in the Great War has been extended to the end of the year with the addition a one-year loan of the Onassis’s Buddha sold at a 2008 Christie’s London auction.

February 4 – September 17, 2017 Hermitage Amsterdam

1917. Romanovs & Revolution

Twelve objects from the Fabergé in the Great War exhibition unveiled late in 2015 in the Fabergé Rooms, General Staff Building, Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg are now on view at the Hermitage Amsterdam venue as part of the 1917. Romanovs & Revolution. A catalog in English and Dutch was published. The venue will travel to Russia to be shown in an expanded form. (Courtesy Marina Lopato, Hermitage Museum)

November 12, 2017 – May, 27, 2018 Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland

Fabergé and the Russian Craft Tradition: An Empire’s Legacy

Objects collected by Henry Walters (1848-1931), art collector and founder of the museum, including the 1901 Gatchina Palace and the 1907 Rose Trellis Eggs by Fabergé and 70 other objects will be shown. A scholarly catalog is planned.

New York City. Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fabergé from the Matilda Geddings Gray Foundation Collection on a rotating basis will be on view through November 30, 2021.

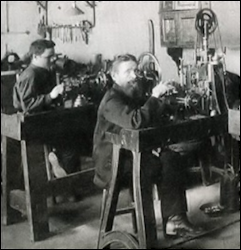

Fabergé Guilloché Workshop

(Archival Photograph)

Small Round Rose Machine 14” and Straight-line Machine in the Lawrence Heyda Studios

(Photographs Courtesy of John F. Logan)

John Atzbach and Karen Kettering will be among the speakers at the August 11-13, 2017, Northwest Jewelry Conference in Seattle (WA).

Newsletter reader Linda Woytisek writes: My husband and I traveled recently from New Jersey to South Carolina, a distance of 660 miles. To break the trip up we stopped in Richmond, Virginia, where we were fortunate enough to view the Pratt Collection of Fabergé at the Virginia Museum Fine Arts just a few days after it had reopened to the public. The new interactive exhibits are worth the trip, and I would highly recommend to everyone interested in Fabergé, excellent museum exhibits, and history to view this exhibition. It is worth the travel! Many thanks for a great newsletter.

Mark Stewart Productions announced its award-winning documentary film, Fabergé: A Life of its Own, will be released on iTunes, On Demand, DVD and Blu-ray on April 10, 2017. The film includes stunning new images of the world’s most valuable Easter egg: Fabergé’s “Winter Egg” of 1913.

Toby Faber, author of Fabergé’s Eggs (2008) will give a lecture on the Imperial eggs in the Guildhall, Bath (UK) on June 5, 2017. Sponsored by the Bath Decorative and Fine Arts Society.

Tatiana Gennadievna Samoilova, deputy chief editor, “Russian Jeweller” magazine, and Valentin Skurlov, independent researcher, St. Petersburg, shared recent coverage of Russian out-door monuments honoring Carl Fabergé (LINK 1 and 2)

An electronic copy of the out-print (OP) book by Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm, The Russian Imperial Award System during the Reign of Nicholas II, 1894-1917, 2005, is available for in-house use at the Liddicoat Library. The reference volume delves into the Russian Imperial Award System, its recipients and the jewelers and makers of the these coveted awards including the highest orders – St. Andrew, St. Catherine, St. Vladimir First Class, St. Alexander Nevskii with diamonds and the White Eagle with diamonds, and the diamond portrait badge. (At press time a few hard copies of this OP title have been found, contact the author)

de Guitaut, Caroline, Fabergé in the Royal Collection, 2003, is a catalogue raisonné of the British Royal Collection of Fabergé, one of the largest and most varied collections in existence. The venue was shown in Edinburgh, Scotland, and London during 2003-2004. The book is now available as a PDF.

Kiaran McCarthy, author of the recent book Fabergé in London: The British Branch of the Imperial Russian Goldsmith, 2017, is interviewed in “Fabergé in London: How Russian Tsarist Jewelry Was Adored in Britain. Russia Beyond the Headlines, February 13, 2017.