Newsletter 2021 Spring and Summer

- In Memoriam Tributes – Part II

- Tiara Research: In Search of Historic Truth – Hermitage Museum Exhibition

Carl Fabergé Memorial Plaques – On September 17, 2020, fifty persons gathered in Wiesbaden, Germany, to remember the 100th anniversary of Carl Fabergé’s (1846-1920) death. Plaques honoring Fabergé were installed during the festivities in Germany and also in Pully, Switzerland, where the honoree died. Readers interested in the event’s press coverage may contact Horst Becker, the organizer of the event.

Plaques Honoring Carl Fabergé, Wiesbaden, Germany, and Pully, Switzerland

(Courtesy Horst Becker)

Wartski Podcast – The British jeweler Wartski commemorated in a podcast, The Centenary of Peter Carl Fabergé’s Death. Their website introduction:

Tatiana Faberge Family Archives – The Moscow Kremlin Museums became the recipient of the Fabergé family archives bequeathed earlier this year [September 2020] by its former owner and direct descendant, Tatiana Faberge, the great-granddaughter of the Russian court jeweler Carl Fabergé (1846-1920). She died in France in February 2020, and according to her will, the museum received the bulk of the family’s archival documents for the purposes of research and study. The specialists of the Moscow Kremlin Museums had known Tatiana Faberge since 1992, when a landmark project – The World of Fabergé – was among the first in Russia to pay the exclusive tribute to the heritage of the master (Moscow Kremlin Museums Press Release; more information with illustrations in Kulikovsky, Ludmila and Paul, eds. Romanov News, #151, October 2020)

Marina Lopato Tribute and Her Posthumous Article – Lucy Morton, editor of the British Silver Society Journal, published annually since 1990, has generously shared three articles from a recent issue (#36, 2020):

- an obituary [p. 114]

- a posthumous article both connected to the late Marina Lopato [pp. 40-45]

- archival research by Barry Shifman for a Fabergé tureen recently acquired by the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond, USA [pp. 104-105, see Exhibitions and Museums section below]

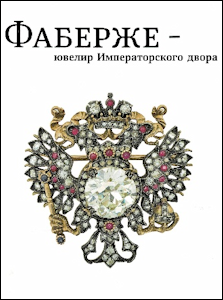

Marina Lopato (1942-2020). For nearly 50 years, Curator of Silver in the Western European Department, Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg (Leningrad), Russia. The Fabergé, Jeweller to the Imperial Court Hermitage Museum exhibition (November 24, 2020 – March 14, 2021) complete with an opening tour video is dedicated to the late Dr. Marina Lopato. Click HERE for her obituary. (Photograph and obituary used with permission, Silver Studies: The Journal of the Silver Society, #36, 2020, p. 114)

Exhibition Catalog: Baboshina, T. V., and Marina N. Lopato. Фаберже – ювелир Императорского двора (Fabergé, Jeweller to the Imperial Court). St. Petersburg: Hermitage, 2020. Approx. 150 color illus., Russian with title page and summary in English. (Courtesy Bronze Horseman Books)

Translated by Catherine Phillips, Professor, European University in St. Petersburg, Russia. The entire article is courtesy of Silver Studies: The Journal of the Silver Society, #36, 2020, pp. 40-45.

Introduction from the published article:

Dr. Lopato’s posthumous article addresses “A History of Fakes” and “Why Fabergé?” Her conclusion states…

The current Hermitage Museum exhibition honoring the late Marina Lopato opened online November 24, 2020 – March 14, 2021 to the public in the spacious spaces of the St. Peterburg museum. It presents works created more than 100 years ago by Carl Fabergé (1846–1920), the celebrated jeweler and outstanding master of the jeweler’s trade. The new display in the Armorial Hall of the Winter Palace was opened by Mikhail Piotrovsky, General Director of the State Hermitage in St. Petersburg, Russia, with these words:

A summary of the objects shown in the exhibition are enumerated on the Hermitage Museum website along with specifics:

- A scholarly illustrated exhibition catalog, Faberzhe – iuvelir Imperatorskogo dvora (Fabergé, Jeweller to the Imperial Court, 2020), has been produced by the State Hermitage publishing house for the exhibition. In Russian.

- The catalog has a foreword, “Fabergé Is Back in the Winter Palace” by Mikhail B. Piotrovsky, General Director of the State Hermitage:

“The large-scale character of the business, the abundance of stylistic devices, the host of participants in the process, including first-rate crafts people, high prices and the complicated fates of creators, clients, new and former owners–all of those things gave rise to massive activity by followers, imitators and forgers. The authenticity of each fresh item that appears on the market can always be disputed and will be. Documents, receipts, the presence of a maker’s mark are no more than a partial help. The consensus of the expert community is not easy to obtain and is often lacking. That is why any kind of new publication is accompanied by discussion. And it is quite right when every new exhibition brings with it, round tables discussing general and specific issues.”

- The exhibition curator, author of the concept and the introduction to the catalogue is the late Marina Nikolayevna Lopato (1942–2020), Doctor of Art Studies, Head of the Artistic Metal and Stone Sector in the State Hermitage’s Department of Western European Applied Art (1978–2020), curator of the exhibition “Fabergé: Imperial Jeweller” in the State Hermitage in 1993. Lopato’s admonition in the Silver Studies journal article to use “archival work to advance Fabergé studies” and the challenges in Piotrovsky’s foreword were kept in mind by newsletter contributors (DeeAnn Hoff, Christel Ludewig McCanless, James Hurtt, and Fabergé enthusiasts worldwide), who in the current edition of the Fabergé Research Newsletter take a closer look at three objects – a tiara and its provenances, an egg, and a set of seven vases, all seen in the Hermitage opening tour video. Readers of the newsletter are invited to be the judge of five case studies in this newsletter series, “In Search of Historic Truth”, if Dr. Marina Lopato’s goals for researchers almost 30 years after the first Fabergé exhibition in Russia, and those stated in Dr. Mikhail Piotrovsky’s 2020 foreword, have been met.

| 1 | The state-of-the-art exhibition with its accompanying scholarly publication co-authored by Géza von Habsburg and Marina Lopato appeared in Russian, English, and French editions with this title, Fabergé: Imperial Jeweller. Co-organized by the Fabergé Arts Foundation, Washington (DC), the venue began at the State Hermitage Museum (St. Petersburg, Russia) in 1993, traveled to the Musées des Arts Decoratifs (Paris) in 1993-94, and to the Victoria and Albert Museum (London) in 1994. The monograph of 476 pages includes 369 illustrations of objects, photographs, and drawings. |

| 2 | Gafifullin, Rifat. Изделия фирмы Фаберже конца XIX – начала XX века в собрании ГМЗ “Павловск” (Works by the Fabergé Firm Late Nineteenth to Early Twentieth Century in the Collection of Pavlovsk State Museum Reserve) IX/I, St. Petersburg, 2013 (Pavlovsk State Museum Reserve Full Collection Catalogues). |

Unresolved Provenances

A tiara/diadem of unknown origin is illustrated in an auction catalog (2011), and four exhibition catalogs for venues in Istra near Moscow, Russia (2019), Amsterdam (separate Dutch and English editions, 2019), and the Hermitage Museum (2020). The recent St. Petersburg venue entitled, Fabergé, Jeweller to the Imperial Court, closed on March 14, 2021. Sketchy and non-matching object descriptions along with a series of questions from readers have not unveiled any archival provenance details for a tiara. In a three-part series, “In Search of Historic Truth”, the criteria outlined in the foreword of the St. Petersburg catalog “Fabergé Is Back in the Winter Palace” by Mikhail B. Piotrovsky, General Director of the State Hermitage, were used to study the tiara attributed to Fabergé:

Fabergé Research Newsletter readers are invited to draw their own conclusions after analyzing the data presented in the essays (part 1 and 2) and the reader observations (part 3). One reader suggested an approach to consider are timeline comparisons, documentation available for review, and aesthetic issues.

Purple statements include additional information, and/or [missing, incorrect, or inconsistent] data points.

set with old-cut diamonds, some with tassels. Gross weight: 92 grams, 19th century.

Thanks to the staff of the La Gazette Drouot the auction has been identified = O.

Doutrebente, November 10-11, 2011, Lot 358. Price realized unknown.

[Not attributed to Fabergé. No workmaster nor hallmarks listed in the description.

Does this style of tiara date it to the 1830’s -1880?]

Excellence (December 15, 2018 – March

24, 2019), New Jerusalem Museum

and Exhibition Center, Istra, Russia.

Exhibition Catalog in Russian by A.

Ivanov and Marina Lopato, 2019.

(Tiara, p. 122).

[Auction lot (left) states a weight of 92

grams, Istra catalog states 104 grams. Is

the difference the larger old-cut diamond

added to the top of the tiara?]

Alf van Beem, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

C.- D. Jewels! The Glitter of the Russian Court: Jubilee Exhibition #2

(September 14, 2019 – March 15, 2020), Hermitage Amsterdam,

the Netherlands. Separate catalogs (2019) with the exhibition title

published in Dutch (3270 copies) and in English (750 copies)

(Tiara, p. 197).

Resources: ‘Jewels!’: Over 300 Pieces of Historical Jewellery from

the St. Petersburg Hermitage Are Exhibited in Amsterdam

Videos: Juwelen! Schitteren aan het Russische Hof in Hermitage

Amsterdam, September 24, 2019 Rondleiding tentoonstelling

‘Juwelen’ in Hermitage, April 28, 2020

E. Fabergé, Jeweller to the Imperial Court, November 25, 2020 – March 14, 2021),

Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, 2020, catalog with the same title. In Russian.

(Tiara, pp. 32-33).

Opening of the exhibition (video), Fabergé, Jeweller to the Imperial Court

None of Piotrovsky’s criteria recommended for review – documents, receipts, the presence of a maker’s mark – are listed nor illustrated in the tiara provenances of the above five publications (A.-E.). So, one can only assume, they are not known from archival data. The workmaster designation in all object descriptions (B.-E.) for the so-called “Fabergé tiara” is absolutely incorrect. Why?

- Mikhail Perkhin (active 1886-1903) as the stated workmaster for the tiara/diadem is not a match based on known archival research about Fabergé’s second chief workmaster. The various dates suggested for the tiara are ca. 1880, 1880s, and 1904, and others on the Internet – 1885, and before 1895. Incidentally, Perkhin had died by 1904!

Specific biographical data – Mikhail Perkhin (born in 1860) was 20 or 25 years old when the tiara was made in three of the suggested dates (1880, 1880s, 1885). After being a journeyman for seven years, he earned his proficiency as a journeyman in 1884, and collected his master’s papers in 1886, and was appointed a head workmaster in 1888. The Perkhin shop did not make objects of this type. Caveats exist for biographical details (Tillander-Godenhielm, Ulla. Fabergé: His Masters and Artisans, 2018, pp. 71-72), and for a visual overview of Fabergé objects from the Perkhin goldsmith workshop (pp. 70-85). Mikhail Perkhin died in an insane asylum on August 28, 1903 (Faberge, Tatiana, and Valentin Skurlov, History of the House of Fabergé, 1992), and his workshop was taken over by Henrik Wigström, Perkhin’s assistant and right-hand man. - A tiara enthusiast visited the Hermitage Amsterdam exhibition. In a subsequent blog, a more likely workmaster source is suggested, since the tiara is ‘so heavy’ and could not be Fabergé. Is it the father and son family business with successive workshops of August and Albert Holmström known for their tiara skills, rather than from Mikhail Perkhin? The Holmström workshop specialized in fine jewelry.

That begs the question is there any proof in the extant Holmström design sketches? The answer is – None are known! The article, Fabergé Tiaras and the Unveiling of an Acquisition by Christel Ludewig McCanless and Kristin Mills in the Fabergé Research Newsletter, Fall and Winter 2019, visually demonstrates the contrast between a heavy, and two light and airy tiaras made in 1903-1904. Tiara Styles: Heavy (Hermitage, 2020, pp. 32-33)

Tiara Styles: Heavy (Hermitage, 2020, pp. 32-33)

(Photographs Christie’s Geneva) Light and Airy 1903-1904 Fabergé Tiaras with

Light and Airy 1903-1904 Fabergé Tiaras with

Documented Archival Provenances Made for Two

German Princesses Sold in May 2019.

(Photographs Sotheby’s Geneva) - Tiaras/diadems matching the object in this study were probably not purchased by the Russian Imperial Court during the Russo-Japanese War, 1904-05. (Guzanov, A., and R. R. Gafifulin, Fabergé Items of Late XIX – Early XX Century in the Collection of the State Museum of Pavlovsk, 2013. In Russian. The book’s appendix contains a chronological list of purchases made by members of the Romanov family from the Fabergé firm. Only one “diadem from the finest 29 personal brilliants, charged to Alexandra Feodorovna’s account for 200 rubles [equivalent to the purchase price of a Fabergé cigarette], February 1904”, is cited. (Entry #4825, p. 263) Why would the ladies of the Imperial court buy new tiaras during war time when it is known from such scholars as Tatiana Faberge, et al. that no eggs were made by the Fabergé firm as Imperial presentation gifts? Are the tiaras a part of the Imperial crown jewels, or private property?

- Other scholarly publications on this topic, Munn, Tiaras: A Taste of Splendour, 2001, pp. 268-323, Fabergé Research Newsletter, Winter 09-10 | Spring 13 | Fall and Winter 19; Christie’s Collecting Guide: 10 Things to Know about Tiaras

The usual pattern for provenance research has two parts:

- Presence of hallmarks for precious metals with country of origin, hallmarks for workmasters and firm. [Since no hallmarks are shown in five catalogs, the phrase, no apparent marks, is applicable for all objects in this tiara study.]

- History of provenance. [No archival documentations or citations of where provenances appeared in print are published for verification, therefore, no general or specific issues as suggested in the Piotrovsky foreword can be discussed.]

A comparison of the original object description and its translated text for the publications (A.- E.) reveal random non-matching provenance statements and other inconsistencies.

| ORIGINAL CATALOG TEXT | TRANSLATED TEXT |

|---|---|

| A. Lot n° 358 Résultat : Non Communiqué Diadème en or et argent à décor feuillagé entièrement serti de diamants de taille ancienne, certains en pampilles. Poids brut: 92 g XIXe siècle |

A. Gold and silver tiara with foliage decoration entirely set with old-cut diamonds, some in tassels. Gross weight: 92 g 19th century. [It is now known the object was Lot 358 in the French auction, O. Doutrebente, November 10-11, 2011, price realized unknown.] |

B.

|

B. Tiara Firm K. Fabergé; workshop of M. Perkhin [?] Saint-Petersburg: [1880s] Gold, silver, diamonds, brilliants; 8 x 14 [centimeter or inches?] Fabergé Museum, Baden-Baden Belonged to Empress Maria Feodorovna (Istra, 2019, p. 122) |

C. Dutch Catalog, pna.

[No gold mentioned, Provenance Unknown] C.- D. Amsterdam, 2019 – Jewels! The Glitter of the Russian Court: Jubilee Exhibition #2 |

D. English Catalog, Lot 308, p. 197

[Size, 80 x 104 cm (sic) converted into English measurements makes it huge at 31.5 x 41 in.] |

E. Hermitage, 2020 – Fabergé, Jeweler

to the Imperial Court, pp. 32-33 |

E. Tiara of Maria Feodorovna Saint-Petersburg [1880s] Carl Fabergé firm; workshop of Mikhail Evlampievich Perkhin [?] Gold, silver, diamonds, brilliants; casting, hammering, engraving, polishing 8 x 14 cm [Finally correct!] Fabergé Museum, Baden-Baden Acquired in 1999 [out of sequence] 1880s – 1917 – property of the Empress (since 1896 – the dowager Empress) Maria Feodorovna 1920 – acquired Armand Hammer via Antikvariat/Antique [1920-1989 – in a private collection, Denmark] (discussed in part 2 of this series) 1989-1999 – in a private collection, Western Europe Exhibitions: Istra, 2019 p. 122; Amsterdam, 2019, p. 197 Caption: The tiara was presented by Alexander III to the Empress Maria Feodorovna in the 1880s. |

Descriptive data from five catalogs (2011 auction catalog, four Russian catalogs in 2019-2020) in which the tiara is shown yields endless inconsistencies. Comparative data as presented below with published or cited archival documentation and photographs would avoid such pitfalls.

Name of the object: The terms diadem and tiara are used alternatively, and on a didactic label at Hermitage Amsterdam Museum the object is “identified more correctly as a kokoshnik-style diadem”. [Is that a correct designation?]

Materials used:

- Gold, silver and diamonds

- Gold, silver and diamonds [Tiara has at the top a larger diamond, but otherwise appears to match the auction lot (A.), but without a provenance.]

- Silver and diamonds [no gold mentioned, weight with the larger diamond now on top has increased from 92 grams to 104 grams (A.-B.)]

- Gold, silver, diamonds

- Gold, silver, diamonds

Workmaster’s mark with city/assayer’s mark:

- -E. None given

- -E. All cited as Fabergé [Where is the documentation? Mikhail Perkhin as the stated workmaster for the tiara/diadem is not a match based on known archival research about Fabergé’s second chief workmaster. Incidentally, Perkhin had died in 1903, i.e., before 1904 cited in C. below as the date of manufacture.]

Date made based on the marks [none stated or illustrated] and city of manufacture (B.- E. St. Petersburg)

- 19th century

- 1880s

- ca. 1904 [Russo-Japanese War, no tiaras matching the one discussed in this case study were made for Russian Imperial family – Guzanov, A., and R. R. Gafifulin, Fabergé Items of Late XIX – Early XX Century in the Collection of the State Museum of Pavlovsk, 2013]

- ca. 1880 Empress Alexandra Feodorovna [not an Empress until 1894]

- 1880s

Chronological provenance with archival documentation from the inception of the object until it appeared on the auction market, or in an exhibition.

- No data given

- Belonged to Maria Feodorovna

- Dutch edition (left) – Empress Alexandra Feodorovna [became an Empress in 1894] Provenance unknown [appears an original owner is listed in the descriptive text, so why is the provenance unknown?]

- English edition (right) [hopeless confusion between the two Empresses named and the chronological date sequences] [Alexandra was 12 years when she met Nicholas in 1884 at the wedding of her sister Ellla to Grand Duke Serge Alexandrovich in St. Petersburg. Alexandra and Nicholas married in 1894, and she became an Empress at that time. Therefore, 1880 would seem a bit early? A tiara of 104 grams (3.7 ounces) for an 8-year old girl? Surely not!]

1999 Private collection [Date connects to no archival information and is out of chronologial sequence as the text continues below with a different Empress, namely Maria Feodorovana]

1880s presented by Tsar Alexander III [died on November 1, 1894] to Empress Maria Feodorovna (sic)

1920s sold abroad by the Anikvariat [sic, more correctly Antikvariat] Agency

1920s various private collections [specifics please, this is an unchecked assumption for the 1920’s to 1999, ca. 79 years without any documentation?] - 1880s-1917 property of Empress (since 1896 Dowager [more correctly 1894] Maria Feodorovna) 1920s acquired by Armand Hammer via Antikvariat Antiques [Antikvariat/Trade Department, need documentation, not found in any Hammer Galleries publications]

1920s-1989 Private collection, Denmark [specifics needed, this is another unchecked assumption for the 1920’s to 1989, ca. 69 years without any documentation?]

1989-1999 Private Collection, Western Europe [very generic, details please]

Caption: The tiara was given by Alexander III to Empress Maria Feodorovna in the 1880s [Should this not be part of the chronology above in both the Dutch and English catalogs?]

Author’s summary – a simple comparative study unveiled no consistent specific data. Confusing provenances which should be verifiable in archival information with solid research is of no help in either “fully or partially” identifing objects. Nor does this kind of frustration provide any documentation for systematic “round table discussions of general and specific issues”. Additional comments and questions about the history, style and function about the tiara from readers far and wide have been received – join us for a second look in the next two essays!

An analytical study on all the tiaras in the 2020/21 Hermitage exhibition has been published, and is included here for reference purposes. (Courtesy Andre Ruzhnikov)

An Illusory Imperial Tiara and Maria Feodorovna’s Jewel Box

from Yalta, HMS Marlborough,

April 11, 1919

(Pridham, Vice-Admiral Sir

Francis, Close of a Dynasty,

1956, Frontispiece)

(Hermitage Exhibition Catalog: Fabergé, Jeweller to the Imperial Court,

2020, pp. 22-23)

No historical documentation for a tiara attributed to the Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna (1847-1928), the mother of Russia’s last Emperor, on view in a temporary exhibition at the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg (2020/2021) has been found. The Hermitage catalog lacks supporting evidence how the tiara came out of Russia before 1920, and was in a private Danish collection from 1920-1989, and another 10 years in a private collection in Western Europe. An oversized text panel (shown above) for the tiara at the Hermitage Amsterdam (2019) venue suggests “Empress Maria Feodorovna fled to Denmark after the Russian Revolution in 1917. She was able to take a small part of her jewelry collection with her, but the lion’s share remained in Russia and was later partially sold.”

Historically speaking, I disagree with the term ‘fled’ in reference to Maria Feodorovna’s final departure from Russia. For despite the overthrow of the monarchy and the imprisonment of her son Nicholas II and his family in the Urals in 1917, Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna at first vehemently refused to leave. She, along with family members and retainers were eventually held in the Crimea. First at Ai-Todor, the Crimean Palace of her eldest daughter, Xenia (sister of former Emperor Nicholas II) and her husband, Grand Duke Alexander Michaelovich. The party was progressively moved from Djulber, the estate of Grand Duke Peter Nicholaevich, and finally settled into Harax, the estate of Grand Duke George Michaelovich.

Only in 1919, at the urging of her sister Queen Alexandra of England did Maria begrudgingly depart from the Crimea, when her sister’s son King George V agreed to send the battleship HMS Marlborough to retrieve his aunt. The assemblage gathered at Yalta included Romanovs, Yussopovs, and other Russian nobles. The Dowager Empress responded to the entreaties of fleeing refugees and convinced Captain Charles Johnson (1869-1930) to take them onboard. Vice-Admiral Sir Francis Pridham, (Lt. Colonel in his duty on the ship) writes in Close of a Dynasty, 1956, pp. 60-61: “After landing two officers at Yalta to help those who were to come on board HMS Marlborough, and learning that the Empress Maria did not want to embark at Yalta pier, we moved a few miles along the coast to a little cove called Koreiz, …”

A condensed geographical chronology of Maria Feodorovna’s locales from her embarkation in Yalta, to her death in 1928 is found, in as much detail as one wants to explore, in various memoirs contemporary to the period. The HMS Marlborough at last set sail from Yalta on the morning of April 11, 1919, navigating the Black Sea and the Bosporus Strait, bound for Constantinople. Passage through the Dardanelles, completed the transit from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean Sea, arriving at their next port, Malta. Following an eight day stay on Malta, Maria Feodorovna and a number of her entourage, were transferred to the British ship HMS Lord Nelson to continue to their journey to England. Docking at Portsmouth on May 9, 1919, Maria with her sister Alexandra settled at Marlborough House for the next few months. Eventually, Maria returned to her native Denmark, living briefly with her nephew, King Christian X, in a wing of the Amalienborg Palace. To the king’s relief, as he could not control her flagrant expenses (use of electricity was one), she chose to settle permanently at Hvidøre, the holiday villa she owned with her sister just outside of Copenhagen.

A fresh look at the whereabouts of Maria Feodorovna’s extant jewels first during her migration into exile, and then for the 69 (or even 79 years) as an illusory tiara reported in a ‘private collection’ in Denmark and western Europe. Before appearing in a 2011 auction without a Fabergé attribution nor a Russian or Danish provenance, and with an later-added larger diamond at the top of the tiara in these venues – Istra, Russia (2019), in Amsterdam (English edition 2019), there is questionable provenance data listed in the Hermitage exhibition catalog (2020, p. 32):

Maria Feodorovna left Petrograd on May 14, 1916, to join family in Kiev. Already there were Olga, her youngest daughter serving with the Red Cross and nursing soldiers (see 1915 Fabergé Red Cross Egg), and Alexander Michaelovich, the husband of her eldest daughter, Xenia, who was Supreme Commander of the Russian Air Force. Having no sense that her departure from the capital was permanent, Maria did not take a large portion of her resplendent jewel collection; the war was on, and she was going to support the troops, not attend pretentious social events.

The Dowager had a brief visit on November 11 with the Emperor and the heir Alexei when the Imperial train pulled into Kiev Station. By the spring of 1917, Kiev had become increasingly unsafe; on the 15th of March, Nicholas abdicated. On the 5th of April, a small cadre of people including Maria Feodorovna, her two Cossack bodyguards, family members and relatives made their way to a deserted railway siding and boarded a train for the Crimea. Clearly, the timing did not allow a return trip to Petrograd in order to collect money or jewels; the Dowager Empress did lament she was not able to see her son.

With some anticipation of removal to exile, and for the most part blind to the reality of it actually being permanent, Russian imperials and nobility sought to secret away jewels of a value to sustain them through their period of expulsion. In this vein, their choices involved the highest value, portability, and space required to keep them hidden as considerations. Readers familiar with the fitted cases characteristically provided for tiaras from major jewelers (Bolin, Koechli, and Cartier) of the period, will recognize that a tiara would not subscribe to the selection requirements just laid out. Indeed, it would not be in keeping with the flexibility, offering conservation of space, particular to the 76 items which eventually emerged from the Dowager Empress’ Jewel Box. That its contents would have included the tiara listed in the Istra Catalog (2019, p. 122) and Hermitage (2020, pp. 32-33) with dimensions of 8 x 14 cm (3.14 in. high x 5.5 in. long), with or without its fitted case is logistically illogical.

One can mournfully recall how such choices and means of concealment played out in the Imperial Family’s exile and eventual murder in the Urals. Chosen gems – referred to in code as ‘medicines’ – were sewn into the corsets of the imperial daughters, rendering their bodies impervious to the bullets and bayonets of the assassination squad. They were ultimately killed by blows to their heads, using rifle stocks, and gunshots to the head.

Hall, Coryne, Little Mother of Russia: A Biography of Empress Marie Feodorovna, 1999:

In the Crimea, with the Dowager Empress confined within, unkept sailors from the Sevastopol Soviet arrived at Ai-Todor with a search warrant in May, 1917.

- (p. 292) “Soon the room was full of rude, dirty sailors … Dagmar’s clothes were strewn across the floor, the curtains were torn down, the carpet ripped up and broken pieces of furniture were scattered about … They pulled the bedclothes to search the mattress … The officer sat at her desk and gathered up all her letters, along with anything else that had writing on it, put them into a large bag and took them away … The search ensued for some three hours … When they had finished ransacking the bedroom, they moved to her drawing room while Dagmar fumed with anger and indignation.”

- (p. 293) “Although her diaries, photographs and letters were taken, along with a ruby ring which Sandro (Xenia’s husband) had given Xenia on the birth of one of their sons, they left Dagmar’s jewel box, which was standing on the table. Similar searches took place at Tchair and finally Djulber.” (Estates of relatives to which Maria Feodorovna’s family was sequentially moved.)

Not until April 11, 1919, did Dagmar, her relatives and all the retainers she could manage, finally board the HMS Marlborough and depart the country that had been her home for 52 years.

Maria eventually died on October 13, 1928, and was buried in Roskilde Cathedral to the north of Copenhagen. Her nephew, King Christian X of Denmark hardly hid his hope that some of the support he had given to her might be repaid out of her will; and that meant her jewel box.

England’s King George V assigned Sir Frederick Ponsonby, Keeper of the Privy Purse, to the task of returning the jewel box to London. Ponsonby sent banker Peter Bark (Nicholas II’s former finance minister now in exile in England) as an emissary to Denmark to monitor not only what was happening to Maria’s estate in general, but to the jewel box in particular.

Clark, William, Lost Fortune of the Tsars, 1994:

- (p. 161) “Ponsonby with the agreement of Xenia and Olga, had the jewels out of the safe (where Maria’s daughters agreed they be kept so their mother would not give them all away, having a weakness for the woes of Russian emigres), sealed them up in their box and dashed off to the British Legation in Copenhagen. His main instructions were to get hold of the jewel case and send it to Buckingham Palace.”

- (p. 163) It was another six months before the jewel box was finally opened in Xenia’s presence at Windsor. “By the time Xenia was settled in again at Frogmore Cottage, George V was showing the first signs of the illness that was to dog him from then on. It delayed the opening of the jewel box in Xenia’s presence. But the day eventually came (it was May 22, 1929) when George V, Queen Mary and Xenia finally opened Marie’s jewel box at Windsor.” Clarke also states the King commented in his diary: “Some lovely things.”

Ponsonby, Sir Frederick, Recollections of Three Reigns, 1952:

- (p. 472) Ponsonby, who was also present, gave a more detailed description: “The Queen came in with the Grand Duchess (Xenia), who saw the box tied up with tape as she had sent it. Rows of the most wonderful pearls were taken out, all graduated, the largest being the size of a big cherry. Cabochon emeralds and large rubies and sapphires were laid out …” Many jewels from Maria Feodorovna’s Jewel Box are extant today in the British Royal Family collections.

Jewel lists consulted in the search of a tiara:

- Phenix Patricia, Olga Romanov: Russia’s Last Grand Duchess, 1999.

(pp. 261-266) List of Jewels in the Hennel’s Sale of Maria Feodorovna’s Jewel Box, July 18, 1929. – No diadems/tiaras listed. - Krog, Ole Villumsen, et al., Treasures of Russia – Imperial Gifts, 2002.

(p. 364) Diadem – Mentions a ‘1 brilliant – scarlet, 10 carats.

(p. 376) Diadem – Mentions only pearls.

(p. 380) Diadem – Mentions stones for the most part turquoise, and also ‘brilliants’. The last item is in a ‘fitted case’. None of these listed diadems match the tiara in question. - Guzanov, A., and R. R. Gafifulin, Fabergé Items of Late XIX – Early XX Century in the Collection of the State Museum of Pavlovsk, 2013.

(p. 263, entry #4825. In Russian) The book’s appendix contains a chronological list of purchases made by members of the Romanov family from the Fabergé firm. Only one “diadem from the finest 29 personal brilliants, charged to Alexandra Feodorovna’s account for 200 rubles, February 1904”, is cited. There are no tiaras listed for the Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna.

The sequential path of Maria Feodorovna’s Jewel Box from exile in the Crimea, to Denmark, and finally to England, where it was opened in the presence of witnesses has been documented. In the statement of Ponsonby present at the opening, and the jewel lists examined in this research here, there is not even a remote suggestion of a tiara.

Will we ever know the history of a tiara with so many unknowns? The tiara was shown in the Fabergé, Jeweller to the Imperial Court exhibition (catalog pages 32-33) at the Hermitage Museum which closed on March 14, 2021. A special thank you to all the newsletter readers and contributors for sharing their comments – Fabergé Research Newsletter readers are special!

Did the tiara/diadem belong to Maria Feodorovna (1847-1928) or Alexandra Feodorovna (1872-1917)? Are there any photographs or paintings known for either of the empresses with the tiara?

While the lack of the Imperial Easter Eggs in 1904-1905 is very important to the economics of the time, the need to add a new tiara may have been influenced by the absence of formal Court entertainment. The last great imperial ball was held in 1903, and the next great Imperial Court occasion was the 1906 opening of the first Duma in which the ladies were all in full court dress and the empresses wore well-documented tiaras. The 1904 date for the tiara attributed to Alexandra Feodorovna (other published tiara descriptions state Maria Feodorovna) or “without a known provenance” (Amsterdam Dutch catalog), then becomes suspect.

The monograph, Jewelry Treasures of the Russian Imperial Court by Igor Zimin and Alexander Sokolov (2013, in Russian) lists with sketches 300 pieces of jewelry belonging to Maria Feodorovna for the years 1886-1900 (“Appendix 3 Jewelry Album of Maria Feodorovna” (Ювелирные сокровища Российского императорского двора Игорь Зимин и Александр Соколов, Приложение 3 Ювелирный альбом Марии Федоровны). Riana Benko reviewed the list, but did not find a tiara matching the one discussed in these essays with these possible dates (ca. 1880, 1880s, and 1904, and others on the Internet – 1885, and before 1895.

How did tiara survive the revolution? Maria Feodorovna left Russia which means the Bolsheviks would have sold or dismantled it. It was not in the photograph of the confiscated jewels and was not part of the Christie’s Magnificent Jewellery Sale, March 16, 1927. DeeAnn Hoff in “An Illusory Imperial Tiara and Maria Feodorovna’s Jewel Box” (Part 2, In Search of Historic Truth series) answers with a plethora of historical documentation why the tiara could not have been in a Danish and Western European collection for 69 or 79 years.

quite stylish in its time, but became a “marriage piece” with new diamonds and other fragments added.

(Courtesy Ursula Butschal | Royal-Magazin)

The tiara looks more like jewelry from the Georgian period (1714-1840) with the heavily encrusted diamond settings, and does not have the elegance of the later 19th century style of Fabergé. Is the big diamond (weight of the tiara changes from 92 to 104 grams) a later addition?

Does this style of tiara date it to the 1830’s-1880? Another reader suggested the tiara dates to sometime before 1895. If it were made later, platinum would have been used instead of gold and silver.

The stones are quite large compared to Fabergé’s stone selections for pieces whispering over-all delicacy. In Fabergé jewelry, the diamonds are balanced to that delicacy and workmanship, and the settings are quite invisible.

(Courtesy Alf van Beem, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

You are correct about the “skeletons” (armature) on the back of the tiara on a lady’s head – unthinkable!

Was the diamond tiara conceived as a tiara, and perhaps later adapted to more functions? The object appears awkward as a tiara, and was perhaps originally made as a devant de corsage, and in modern times incorrectly identified as a kokoshnik-style diamond diadem. More information: Five Types of Kokoshnik Tiaras.

Newsletter contributor Timothy Adams illustrated the devant de corsage concept:

Mary of Teck (picture photo-shopped to

illustrate application by Timothy Adams)

Topley Studio; Photographer: William James

Topley (1845-1930), Public Domain

via Wikimedia Commons

Adams suggests topics to contemplate before authenticating this tiara or any kind of jewelry, or also applying them to “a round table discussion of general and specific issues”.

Timeline: The dates are not verified or consistent among the publications. They do not make sense in relation to the suggested workmaster Mikhail Perkhin (active 1886-1903) once they are ordered based on his life and career at Fabergé.

Documentation: Where is the documentation that it is a Fabergé tiara? There are not verifiable documents, such as invoices or even production drawings of this piece. There is no mention of hallmarks of any kind, makers mark, scratched stock number, or even a city and metal stamp.

Aesthetic Issues: The tiara looks too heavy, as if it belonged to the earlier Victorian or even Georgian period of jewelry. It does not have the traditional elegant balance and lightness of Fabergé tiaras, nor the Fabergé refinement one would expect from a Fabergé workshop?

Based on his curatorial experience a final word of caution: Curators need to do their own research before they accept an assortment of object details into their exhibitions at face value.

For centuries, artists in a broad spectrum of genre have garnered inspiration from those who created before them. Inspiration is something most artist court. Objects from Fabergé’s workshops, traced to antecedents preserved in the Grüne Gewölbe (Green Vault) in Dresden, Germany, provide but one example. Marina Lopato in her article addresses the phenomenon of Fabergé in our modern age, with both its blessings and curses. She writes, “Fakes, imitations and repetitions represent the most acute problem faced by Fabergé scholars and collectors.” A perusal of the exhibition catalog, Fabergé, Jeweller to the Imperial Court, and a video presentation accompanying the temporary exhibition (November 25, 2020 – March 14, 2021), on display at the historic Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia, brings such descriptive terms to the fore. My essay, “Digital Colorization of Imperial Photographs: A Case Study of Time-Line Inconsistences” (Fabergé Research Newsletter, Spring 2020) shows comparative historical photographs, whose modern colorations found their way onto a 1904 egg first seen in Fabergé Style. Excellence Beyond Time at the Museum and Exhibition Complex, Istra near Moscow, Russia, in 2018-2019.

(Fabergé Style: Excellence Beyond Time, 2019, p. 23; Faberge,

Jeweller to the Imperial Court, 2020, pp. 50-51)

While the egg is variously labeled The Tenth Wedding Anniversary or The Jubilee Egg, the year 1904 was not only the 10th wedding anniversary of the Emperor Nicholas II and Alexandra Feodorovna, but also the sorrowful anniversary marking the death of Nicholas II’s father, Emperor Alexander III. The Emperor’s death at the old Maly Palace in Livadia (the Crimea) was devastating to Nicholas, ill prepared to assume the throne of Russia. Entries from his diary reveal this event would not be one he or the court jeweler Fabergé would have chosen for the annual Easter egg – even IF one were commissioned for that year. More…

(November 2020 – March 2021 Hermitage Exhibition)

Newsletter readers who do not read Russian have an opportunity in this essay to become acquainted with research on seven vases with English language descriptions, supporting scholarly information and outstanding Russian photographs.

- Shown for the first time as a group are seven vases in the Fabergé, Jeweller to the Imperial Court exhibition (November 25, 2020 – March 14, 2021) at the Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. Catalog numbers from the Hermitage Museum publication are used with each illustration and in the text, unless otherwise noted.

- It has been 27 years since six of these Fabergé vases were included in a traveling (Russia, France and the United Kingdom) venue, Fabergé: Imperial Jeweler, 1993.

- Ground-breaking research for six vases by Russian contributors was published by Géza von Habsburg and Marina Lopato in the exhibition catalog accompanying the 2000 Wilmington (DE) exhibit, Fabergé: Imperial Craftsman.

- Archival research from a Russian publication (Guzanov, A., and R. R. Gafifulin, Fabergé Items of Late XIX – Early XX Century in the Collection of the State Museum of Pavlovsk, 2013, p. 210, #3801-3804) is also cited.

- The author’s analysis for an unknown vase is included for readers to share additional supporting documentation.

The late, lamented Marina Lopato exhorts us to pay attention to archival material: More…

(Courtesy A La Vieille Russie, New York)

(Press Release Courtesy Mining University Museum)

Viewing and studying Fabergé objects in museum exhibitions or examining them during auction previews was not possible this past year. Researchers worked without access to archival documentation in museum object files, and libraries were closed. Our email accounts were overwhelmed to keep in touch, and to share research discoveries. Riana Benko, a newsletter contributor from Slovenia, was not deterred as she painstakingly gathered and updated Internet links for permanent and temporary exhibitions, searched for online learning tools in this virtual age, and much more. Best of all, she worked with Dr. Mikhail Shabalov, director of the Mining University Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia, to present for the first time the museum’s outstanding Fabergé collection. Congratulations, great team work!

A special thank you to readers for sharing links, discovering research tools and book resources (both old classics and new ones), writing about venues in the planning stages (checking in advance is advised!), and finding online learning tools (some free of charge, or with paid museum memberships). The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond, Virginia, has a new Fabergé acquisition. We are delighted museums found ways to teach about their collection with fascinating virtual lectures. Until we can meet again in person, please continue to share Fabergé news for the Readers Forum section of the Fabergé Research Newsletter.

Where will your “arm chair travels” take you in 2021?

Family behind the Jewelry Empire

(Courtesy of Francesca Cartier Brickell)

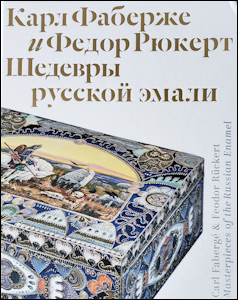

Rückert. Masterpieces of Russian Enamel

by Tatiana Muntian, et al., 2020

(Hillwood Estate, Museum & Gardens / Photographed by Erik Kvalsvik)

(Photo: Travis Fullerton © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts)

Baltimore, Maryland (USA) Walters Art Museum

Monograph by Margaret Kelly Trombly, et al. Fabergé and the Russian Crafts Tradition: An Empire’s Legacy for a 2017-18 exhibition was published on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution. A website index includes links to venues and object description complete with image down-load instructions. Two eggs are in the collection, 1901 Gatchina Palace Egg and the 1907 Rose Trellis Egg.

Carlsbad, California (USA) Gemological Institute of America (GIA)

Articles and webinars shared by Rose Tozer, GIA Senior Research Librarian, enlighten the listener about the broader gem and jewelry connections to Fabergé and his time.

- Gem Virtuosos: The Drehers and Their Extraordinary Carvings includes videos of a Gerd Dreher interview and a demonstration of the Drehers’ tools and techniques by Patrick Dreher, descendants a family gem-cutting business in Idar-Oberstein, Germany, and associated with the Fabergé firm in Imperial times.

- Superstitions Surrounding Gems and Jewelry

- Russia’s Treasure of Diamonds and Precious Stones relates to the Fersman articles published in the Fabergé Research Newsletter Fall 10 | Winter 10-11 | Spring 12 | Spring 13 | Winter 15 | Summer and Fall 16 | Summer 20

Newsletter contributor Timothy Adams is presenting his research, “Fabergé’s Work with Agate and Chalcedony” at the virtual Sinkankas Symposium (pre-recorded, must register for the free event before April 24, 2021) co-sponsored by the GIA.

The Cartiers: The Untold Story of the Family Behind the Jewelry Empire (2019) written by Francesca Cartier Brickell, a Cartier family descendant, tells the revealing tale of a family jewelry dynasty—four generations, from revolutionary France to the 1960s. Seven webinars are available at press time. In the exhibition catalog for the Munich venue, Fabergé – Cartier: Rivalen am Zarenhof (2013). Géza von Habsburg and 12 worldwide contributors discussed in detail the parallel development of two well-known jewelers in Russia and London along with customers worldwide.

(Courtesy of Christie’s Geneva, A Lifetime of Collecting – 101 Cartier Clocks, July 7-20, 2020;

Francesca Cartier Brickell, The Cartiers: The Untold Story of the Family Behind the Jewelry Empire, 2019)

Cleveland, Ohio (USA) Cleveland Museum of Art

The collection of 77 Fabergé objects features the India Early Minshall Collection with the 1915 Red Cross Triptych Egg. Alternative photographic views along with an artist biography, provenance, citations and exhibition history are enumerated to the right of each object.

Clinton, Massachusetts (USA) Museum of Russian Icons Virtual Lectures, Webinars, and Tutorials include a curators’ round table for the “Tradition & Opulence: Easter in Imperial Russia” exhibition.

Copenhagen, Denmark Amalienborg Palace Museum

On display in the Fabergé Chamber are Russian jewelry from 1860-1917, and the Fabergé silver-gilt champagne cooler, a present from the Russian Imperial couple, Alexander III and Maria Feodorovna, on the occasion of King Christian IX and Queen Louise’s golden wedding anniversary in 1892. Martin Hans Borg, chief specialist in Russian art at the Danish auction house Bruun Rasmussen, describes his visit in Join Our Specialist in the Treasury of Amalienborg Palace! To truly appreciate the size of this cooler, see Carole Warner’s article, “Danish Royal 50th Wedding Anniversary Kovsh”, Fabergé Research Newsletter, Winter 2013-2014, and “Anniversary Gifts in the Danish Royal Collection” by Roy Tomlin, Fabergé Research Newsletter, Spring 2015.

Doorn, The Netherlands Huis Doorn

(Museum Huis Doorn, Original Cannon in the Hermitage, St. Petersburg)

The manor house and national museum is the former residence of the last German Emperor Wilhelm II, who fled to the neutral Netherlands in 1918 after the German defeat in the First World War. The article, “Discovering the Kaiser’s Fabergé at Huis Doorn”, Fabergé Research Newsletter, Spring 2015, tells the story of the cannons. A stroll through the E-museum at Huis Doorn and a look at the 2017 National Museum Week article connects the Fabergé object with the original landmark.

Houston, Texas (USA) Houston Museum of Natural Science

The McFerrin Collection Gallery in the Cullen Hall of Gems and Minerals of the museum was made possible by the generous underwriting of the Artie and Dorothy McFerrin Foundation. The collection of more than 600 Fabergé and Russian is the largest private collection of Fabergé in the world. It includes three Fabergé Easter Eggs: 1892 Imperial Diamond Trellis Egg (Fabergé Research Newsletter 02.08 | Winter 11-12 | Summer 14 | Spring 15 | Fall 15 | Winter 15 | Summer 18), 1902 Kelch Rocaille Egg and 1913 Nobel Ice Egg. The “Wonder of Fabergé: A Study of the McFerrin Collection” showcases research presented at the 2016 Houston Fabergé Symposium.

NEW! The “Everyday Fabergé” exhibition opens to the public on April 2, 2021 – March 2023. Featured are desk accessories, bell pushes, cigarette and vesta cases, vanity accessories, time pieces, and more with an emphasis on Fabergé’s workmasters. A booklet with the same title will be available online, or from the museum store late in April 2021.

Jordanville, New York (USA) Russian History Museum

An active lecture series listed in What’s New on their website includes Marie Betteley discussing her book Beyond Fabergé, Imperial Russian Jewelry (2020), Wendy Salmond, The Old Russian Style and the Arts of Nostalgia, Nick Nicholson, Grand Duke Michael: Brother of the Last Tsar, Wilfried Zeisler, Entertaining, Shopping and Collecting in Paris: The Fate of the Collection of Princess Olga Paley and Grand Duke Paul of Russia, and more in their Second Saturday series. The museum’s efforts to restore archival library books through generous donors is commendable.

Lausanne (Switzerland) Olympic Museum

July-August 2021 is the new date for Olympic summer sports in Tokyo, Japan. Will the Summer 1912 Fabergé decathlon trophy in the Olympic Museum collection be on view somewhere? The trophy is featured in “Fabergé’s Monumental Kovshes with Bogatyr Themes”, Part I and Part II in the Fabergé Research Newsletter, Winter 2015, and Summer and Fall 2016?

London (United Kingdom) Royal Collection of Queen Elizabeth II

(Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, 2021)

The Royal Collection is one of the most important and biggest Fabergé collections in the world complete with three Imperial Easter eggs: 1901 Basket of Flowers Egg, 1910 Colonnade Egg, 1914 Mosaic Egg, and one Kelch Egg (Twelve Panel Egg, 1899). Temporary exhibitions feature individual parts of the Fabergé collection. A useful research tool built into the website allows access points to 584 Fabergé objects in the collection, some yet to be illustrated with colored photographs. For example, Erik Kollin (active as a Fabergé work master from 1870-1901) is represented with 18 objects. The 2003 exhibition catalog of the British Royal Fabergé Collection by Caroline de Guitaut entitled Fabergé in the Royal Collection is available for download. Objects can be filtered by category, type, material, technique and subject, and other helpful search criteria (who, what, where, and when). There are at least 450,000 photographs in the Royal Collection, acquired by members of the royal family from 1842 to the present day, including portraits, landscapes and images of the royal residences. A more complete catalogue raisonné of the entire royal Fabergé collection is in preparation.

London (United Kingdom) Science Museum

NEW! A small display about the Trans-Siberian Railway, an extraordinary engineering challenge in the Imperial Russia, will open in support of the major exhibition at the National Railway Museum in York (see below).

Moscow (Russia) Fersman Mineralogical Museum

Among 8000 items made by gems and stones there are also around 30 cut gems lapidary Fabergé masterpieces, functional items, flowers, animals, human figures and Easter presentations. In 1925, Agathon Fabergé was persuaded to donate the personal gem collection of his father Carl Fabergé. The collection consisted of more than two hundred polished gemstones, including emeralds, rubies, sapphires, aquamarines, alexandrites, phenakites; a few mineral specimens; and some gems in the rough. The article entitled Fabergé Lapidary in the Fersman Mineralogical Museum Collection by Marianna B. Chistyakova best describes the Fabergé collection.

Moscow (Russia) Kremlin Armoury Museum

The museum owns 10 Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs never sold in the West after 1918: The 1891 Memory of Azov Egg, 1899 Bouquet of Lilies Clock Egg (or the Madonna Lily Clock Egg), 1900 Trans-Siberian Railway Egg, 1902 Clover Leaf Egg, 1906 Moscow Kremlin Egg, 1908 Alexander Palace Egg, 1909 Standart Yacht Egg, 1910 Alexander III Equestrian Egg, 1913 Romanov Tercentenary Egg, 1916 Steel Military Egg. For interesting views of the eggs, consult the links under the heading СОДЕРЖАНИЕ list on the right side of the page. For more information on the eggs visit our Imperial Egg Chronology Section.

Two simultaneous exhibitions at the Kremlin Armoury Museum:

- CLOSED! “Carl Fabergé & Feodor Rückert. Masterpieces of Russian Enamel”. October 9, 2020 – February 14, 2021, Hall of the Assumption Belfry and Hall of the Patriarch’s Palace. About 400 masterpieces made of precious metal and covered with enamel by Feodor Rückert and Fabergé were on display along with 1906 Moscow Kremlin Egg in the form of the Assumption Cathedral. A theme-based satellite site about the exhibition was launched. Exhibition catalog (shown in our introduction): Tatiana Muntian, Marina Gor’kova, et al. Карл Фаберже и Фёдор Рюкерт. Шедевры русской эмали. (Karl Fabergé and Feodor Rückert. Masterpieces of Russian Enamel), 2020. In English and Russian. Extensive photographic collage and description of the venue in Romanov News, #151, October 2020.

- CLOSED! “Emperor Alexander III, the Peacemaker”. October 14, 2020 – March 1, 2021. Dedicated to the 175th anniversary of the birth of Emperor Alexander III. Extensive photographic collage and description of the venue in Romanov News, #151, October 2020.

New York City (USA) Brooklyn Museum

Sold its Fabergé Collection to Support Museum Collections, December 2, 2020, Sotheby’s London; Review of the Auction (Courtesy Andre Ruzhnikov)

New York City (USA) Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fabergé Venue Closing 2021! A selection of Fabergé works of art from the Matilda Geddings Gray’s collection are on display in Gallery 555: The Lilies-of-the-Valley Basket, 1890 Imperial Danish Palaces Egg, 1893 Imperial Caucasus Egg, and 1912 Imperial Napoleonic Egg. The venue will close on November 30, 2021, after a ten-year extended loan. Future plans are not known at press time.

Richmond, Virginia (USA) Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

22 h. x 29 l. x 20 1/2 w. in. (55.88 h. x 73.66 l. x 52.07 w. cm.) Marks: K. Fabergé, imperial warrant, assay mark of Moscow 1908-1917,

inventory numbers: tray (42744 or 49744); lid (42741); tureen: (16798); ladle (16274 or 16974)

(Courtesy Virginia Museum of Fine Arts)

The Pratt Collection of Fabergé objects and other Russian decorative arts are presented in five galleries with Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs highlighted in the center: 1896 Revolving Miniatures Egg, 1898 Pelican Egg, 1903 Peter the Great Egg, 1912 Tsarevich Egg, and 1915 Red Cross Portraits Egg. The Virginia museum’s five Imperial Eggs with 360° views are a one-of-a-kind treat only found in this collection. The Freeman Library houses the Lillian Thomas Pratt Archives complete with electronic access to a large array of art-related databases. A recent addition (on view beginning July 2021) to the Fabergé collection is a covered tureen, tray and ladle, ca. 1908-1917.

St. Petersburg (Russia) Fabergé Museum

The Collection Highlights include six searchable topics: Category, firm, materials, room, workmaster and date for their 10 Imperial eggs: 1885 Hen Egg, 1894 Renaissance Egg, 1895 Rosebud Egg, 1897 Coronation Egg, 1897 Resurrection Egg, 1898 Lilies of the Valley Egg, 1900 Cockerel Egg, 1911 Fifteenth Anniversary Egg, 1911 Bay Tree Egg, and 1916 Order Saint George Egg, and two Kelch eggs – 1898 Hen Egg and 1904 Chanticleer Egg (for more information on the eggs visit our Imperial Egg Chronology Section), and the Duchess of Marlborough Egg, and many other Fabergé and Russian objects. Visit their YouTube Channel to enjoy the museum’s permanent collection. A video, Как устроены яйца Фаберже — взгляд изнутри (How Fabergé Eggs Work – An Inside Look) has had 5,767,040 views since Jun 20, 2014. Annually since 2014, the Fabergé Museum has sponsored scholarly symposiums relating to Fabergé and the Russian jewelry arts. Annotated summaries of the presentations published the following year are excellent. For updates check out our Fabergé Research Newsletter Summer 2018 and Spring 2020.

NEW! St. Petersburg (Russia) Mining University Museum

The Mining Museum, a part of the University of Mines established in 1774, has a unique and enormous collection of gemstones and minerals as well as some paleontological exhibits in its museum and storage room. Their collection numbers over 240,000 samples collected from over 80 countries of the world. Twenty Fabergé objects are from two sources – 13 of them in 1927 from the Leningrad branch of the State Museum Fund, and 7 objects were bought by the museum in 1946.

(Courtesy Mining University Museum, 2020)

(Photograph Cynthia Coleman Sparke)

From the museum’s press release: “On Friday, December 18, 2020, it became known that the Mining Museum of St. Petersburg had begun cooperation with the Fabergé Research Site. It is the world’s largest portal dedicated to the Fabergé heritage …’The Mining Museum can be justly proud of its magnificent collection. For all connoisseurs of Carl Fabergé’s works, it is a great success to see such rare objects even in photographs,’ said Riana Benko, representative of the Fabergé Research Site … It should be noted the international organization has been gathering materials about the collections and items of work of the famous Russian jeweler around the world for fifteen years. During this time, over fifty issues of newsletters have been published. Among the partners of the association are the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Houston Museum of Natural Science, the Royal Gallery of Buckingham Palace.” (Romanov News, #153, December 2020)

There are 11 carved decorative animal figures and 9 decorative items and table decorations. Ten possibly came from the palace of the Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna: hare, ram, hippo, goose, three bonbonnieres (one made by workmaster Mikhail Perkhin and one by Erik Kollin), and a floral composition of daisies with an original case. Two parrots on a perch (one by work master M. Perkhin, and a decorative basket, probably from the Wigström studio and then from the Yousupov Collection. (Email from Dr. Mikhail Shabalov, director of the Mining University Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia)

St. Petersburg (Russia) State Hermitage Museum

In 2011, the Fabergé Memorial Rooms (#301–302) were opened in the General Staff Building complete with a virtual tour. The 1902 Rothschild Egg by Fabergé was donated in 2014 to the Hermitage Collection. Fabergé, Jeweller to the Imperial Court venue was on view from November 25, 2020 – March 14, 2021. The “In Search of Historic Truth” series in this Fabergé Research Newsletter attempts to find archival documentation for a tiara, an egg, and vases shown in a temporary exhibition.

St. Petersburg (Russia) State Museum Pavlovsk

Guzanov, A., and R. R. Gafifulin, Fabergé Items of Late XIX – Early XX Century in the Collection of the State Museum of Pavlovsk, 2013. The first full publication about 34 Fabergé items belonging to members of the Imperial family now housed in the Pavlovsk Palace Museum. The book’s appendix contains a chronological list of purchases made by members of the Romanov family from the Fabergé firm. In Russian. The content of the Fabergé collection is not on the Internet.

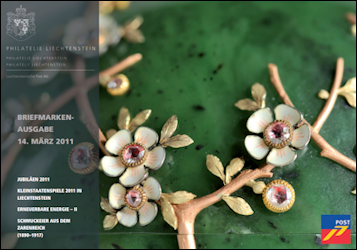

Vaduz (Liechtenstein) Liechtenstein National Museum

“Apple Blossom Egg” by Fabergé. Gold, diamonds,

nephrite, enamel. St Petersburg, 1901.

Craftsman: Michael Evlampievich Perchin.

© Liechtenstein National Museum.

Collection Adulf Peter Goop

(Photograph Sven Beham)

© Liechtenstein National Museum

(Photograph Sven Beham)

The Treasure Chamber displays more than 100 eggs from all over the world, some made by Karl Fabergé and Alexander Edward Tillander. A highlight in the museums’ collection is the 1901 Fabergé Apple Blossom Egg, a gift of Alexander Kelch to his wife Barbara Kelch-Bazanova donated to the museum in 2010 by the Adulf Peter Goop (1921-1911). (Thank you Donat Büchel for all of your assistance.)

Washington, District of Columbia (USA). Hillwood, Estate, Museum & Gardens

An amazing variety of ways to learn about Hillwood’s current, future and past exhibitions, the life of its founder, Marjorie Merriweather Post and her collections, and so much more:

- Explore Hillwood from Home

- Study their Fabergé objects in detail, and view the 1896 Twelve Monogram Egg and 1914 Catherine the Great Egg.

- Select from their well-populated YouTube channel

- Get a sneak preview on exhibitions, past and present, and one recently closed

For more encounters, become a treasured Hillwood member to receive advance notices about all their happenings!

York (United Kingdom) National Railway Museum

Trans-Siberian Railway Exhibition to Show Fabergé Gems on March 26, 2020 – September 5, 2021 (dates vary). The Fabergé Imperial 1900 Trans-Siberian Egg commemorates the Russian railroad spanning 5,772 miles across seven time zones, completed on October 5, 1916, after 25 years of engineering ingenuity. Related venue at the Science Museum in London (Shared by Katrina Warne, UK)

Dealer News:

A La Vieille Russie, New York City. The dealer’s recent Christmas catalog published annually since 2001 has a new look, a flip book. Hard copy printed catalog available from the shop with Fabergé objects beginning on page 138.

Peter Schaffer, director of the New York A La Vieille Russie shop, in an interview with Ann Loynd Burton about collecting authentic Fabergé in “The Story Behind the World’s Most Renowned Fabergé Dealer”, Gallerie Magazine (New York), March 6, 2020.

Bronze Horseman Books, Larchmont, New York, website of John Emerich, importer of exhibition and collection catalogs from leading Russian museums.

After a move to a larger warehouse and while libraries and museum archives are closed, Jeff Eger Auction Catalogues initiated a new reference service, “Art and Provenance Research at a Distance”. His warehouse inventory includes auction catalog holdings, back issues of art periodicals, thousands of art books, exhibition and dealer catalogs.

Ruzhnikov Publications features two new online publications – The Nephrite Collection and Collection of Hardstone Animal Carvings in his Works of Arts series.

Books, Journals and Videos:

Paul Gilbert (Canada) on his Tsar Nicholas website has a brief video with fascinating background information about The Romanov Family Photo Albums at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, as well as the story of the 1982 book with a similar title, and a direct link to the digital collections of the Romanov Archives at the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University. Also, on the Gilbert website is an article entitled Bolshevik Sale of the Romanov Jewels.

Kathy Maxwell (Australia), “Lost Fans of the Russian Crown Jewels” in Fans, The Bulletin of the Fan Circle International, Autumn 2020, No. 109, pp. 29-39, began her fan study by consulting the Fersman Portfolio, Russia’s Treasure of Diamonds and Precious Stones, Moscow: People’s Commissariat of Finances, 1925–26. Her profusely illustrated, scholarly article is quite an addition to the studies of the Fersman catalog, a four-part set under the leadership of a Soviet-appointed commission led by Alexander E. Fersman (1883-1945), a geochemist, mineralogist and director from 1919 to 1930 of the Russian Mineralogical Museum founded in 1716 in St. Petersburg. A small number of surviving catalogs (separate editions in Russian, English, French and German) helped in promoting the sale of Russia’s crown jewels in 1926. Fersman Portfolio research studies appeared in the Fabergé Research Newsletter in Fall 10 | Winter 10-11 | Spring 12 | Spring 13 | Winter 15 | Summer and Fall 16 | Summer 20.

From time to time the video first shown on April 15, 2018, about the most expensive Fabergé item on the popular BBC Antiques Roadshow is rerun in various publicity mediums. If you missed it, enjoy this special treat featuring a Fabergé flower with an unusual history discussed by Geoffrey Munn, managing director of Wartski, London, before his retirement.

“Géza von Habsburg in an Interview” with Sneha Bhura on September 23, 2020, in The Week Magazine India suggests “There are Easter eggs and then there are Fabergé eggs.”

“Fabergé Eggs: 8 Little Known Facts”, Bbys (Barneby’s) Magazine, April 15, 2019.

Book review by Timothy Adams in Gems & Jewellery, Spring 2021, pp. 42-45, of Beyond Fabergé: Imperial Russian Jewelry by Marie Betteley, 2020.

Toby Faber, author of Fabergé’s Eggs, the Extraordinary Story of the Masterpieces That Outlived an Empire (2008), recently spoke to the Spanish Arts Society Costa del Sol via Zoom.