Newsletter 2021 Fall

- Diamond Bow Brooches Attributed to Fabergé Surfaced in the Last Ten Years – What Are Their Stories?

- Fresh Look at Fabergé-Mounted Glass Vases in the McFerrin Collection

- For Whom the Bell Rings – A Tale of Two Bell Pushes

- Visions of Byzantium: Fabergé Byzantine-style Cups

- Preservation Techniques for Fabergé Objects and More: Experts Answer Your Questions

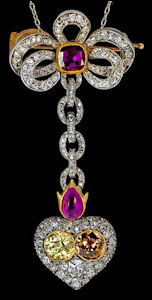

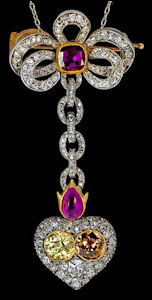

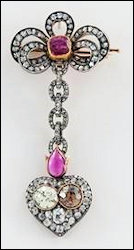

At first glance three color photographs of diamond-studded bows with a heart-shaped pendant appear to have minor differences. Could they be the same object? The descriptions of a brooch/pendant/illustrated as a necklace were published by an auction house (2011), a dealer (2012), and acquired by a private collection (2013), and then unveiled in the McFerrin Foundation catalogue raisonné1 (2016). The history of the objects, or perhaps the same object, have not been studied in any detail, and a few unsolved inconsistencies will require further study with the object(s) in hand. Auction house catalogers, dealers, collectors, and museum curators have the added advantage of examining, comparing, and photographing a specific object, while Fabergé enthusiasts in their research must rely on the printed word and available photographs. In our case study, archival finds for one or possibly the three similar brooches are discussed for the year 1896, and then again for the 2011-2016 time period. Newsletter readers are invited to review the details gathered here and share their thoughts in a further attempt to solve the mysteries covering a time gap of more than a century.

Verbatim Descriptions from Finnish and American Publications

Provenance: “Purchased by jeweler Rabinowitsch in St. Petersburg before the Russian revolution. A family heirloom.” This text in the auction catalog is possibly an error in that the dealer [Jack] Rabinovitch (sic) who brokered the 2013 sale of the brooch to Artie and Dorothy McFerrin died ca. 2015, and was not alive during the Russian revolution [1917]. There are no provenances listed with this lot. Price Realized at auction €5,000.

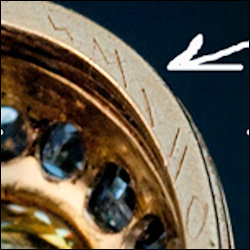

(B.) Romanov Russia Website (2012): “An Antique Victorian Era Flaming Heart Pendant/Brooch by Carl Fabergé, St. Petersburg, Russia, circa 1897. The heart shaped pendant is highlighted with two fancy colored yellow and brown Old European cut diamonds (approximately 0.61 and 0.65 ct.) in yellow gold collet settings, surrounded by white diamonds pave set in silver over rose gold. The yellow gold stylized flame over the heart is set with a cabochon drop shaped ruby. The silver bow is centered with a cushion cut ruby in a gold rub-over collet setting. The bow and the chain are encrusted with single and rose cut diamonds. Length 2 1/8 in. (5.5 cm) Marked on the pin guard with 56 zolotniks gold standard (14K-583) and St. Petersburg coat-of-arms. The pin is struck with St. Petersburg assay mark and initials ‘AH’ of Fabergé’s principal jeweler August Holmström (born 1829 – died 1903). Original Fabergé scratched inventory number 54140 on the back on the gold frame. The top rim of the gold frame is marked with St. Petersburg arms and scratched inventory number 54140. Fabergé’s scratched inventory number 54140 on the back of the heart pendant.” There are no provenances listed with this lot. (Ed. Note: James Hurtt in an e-mail exchange with the owner of the Romanov Russia website was told he had purchased the item from a dealer and sold it to a dealer.)

(C.) McFerrin Collection (2013): “Brooch by Fabergé, workmaster August Holmström, St. Petersburg, ca. 1900. Diamond-set jeweled brooch featuring a diamond-set heart suspended on a diamond-set chain from a diamond-set ribbon garland, with a ruby cabochon at the center set in a gold bezel. It is connected by a chain to a heart with a second tear-drop shaped ruby cabochon at the center. The diamond-set heart contains two colored diamonds; a green-yellow diamond on the left and an orange-brown diamond on the right. Marked Fabergé with workmaster’s initials [AH]

In the book Fabergé: The McFerrin Collection – The Opulence Continues… 2016, p. 86, Accession No. 424: “Brooch, Fabergé workmaster August Holmström, 56 standard, scratched inventory number 54140, St. Petersburg, ca. 1895. Jeweled brooch featuring a heart suspended on a chain from her ribbon garland-all diamond set. The ruby cabochon at the center of the ribbon is set in a gold bezel. It is connected by a chain to the heart with the second teardrop shaped ruby cabochon at the center. The heart contains two colored diamonds.” The only known modern provenances for the brooch cited with the McFerrin Brooch are the antiques dealer “John Atzbach, a U.S. Private Collection, and Jack Rabinovitch”, a dealer who died ca. 2015.

The McFerrin brooch is on view2 from April 2021 – March 2023 in the McFerrin Gallery, Houston Museum of Natural Science in Texas. At newsletter press time, close-up photographs of the McFerrin object’s marks are not available for comparison with the five marks (B.) shown in detail on theRomanov Russia website.

A descriptive data chart (A.-C.) for the years 2011-2016 became our research tool as we debated the pros and cons in the endless stream of emails.

| ITEM |

(A.) Brooch

|

(B.) Pendant-brooch

(shown as a necklace) |

(C.) Brooch

|

| WORKMASTER | AH |

AH |

AH |

| DATE | (active 1857-1903), made in 1880’s. | (active 1857-1903), made ca. 1897. Birth and death dates (1829-1903) are cited in the dealer’s text. | (active 1857-1903), made ca. 1900, later the year was changed to 1895. |

| STOCK / INVENTORY NUMBER | None cited, not identified as Fabergé. | Marked three (3) times with stock number 54140 on different parts of the object, total of five (5) marks in different spots on the object, text states Fabergé, no such identification shown on the object. | 54140, text states Fabergé, not all marks available for the piece, since it is on view in a Texas exhibition until March 2023. |

| PROVENANCE | This text in the auction catalog is possibly an error in that the dealer [Jack] Rabinovitch (sic) who brokered the sale of the brooch in 2013 to Artie and Dorothy McFerrin died ca. 2015, and was not alive during the Russian revolution [1917]. There are no provenances listed with this lot. | No provenances cited. An undated Pinterest entry has a collage of the above diamond bow brooch photograph from the Romanov Russia website flanked by a well-known 1885 autographed photograph of Empress Maria Feodorovna by the Russian photographer, A. A. Pasetti, and an incomplete, unidentified brooch sketch dated July 1896. The collage lacks any bibliographic data, and how and why the images relate. | Provenance in Russian Imperial times unknown. McFerrin book in 2016 cites contemporary provenance details: John Atzbach (dealer, U.S. Private Collection, Jack Rabinovitch, dealer in 2013 (died ca. 2015). |

Photographs

- If the three brooches (A.-C.) are one and the same, why the sagging bows (A.-B.)?

Photographic angles along with lighting and the placement of the object need to be considered. - Has the pendant/brooch/necklace (B.) illustrated with ten close-up photographs on the Romanov Russia website been restored or customized to be called a pendant, a brooch, a convertible pendant-brooch, and even a necklace?

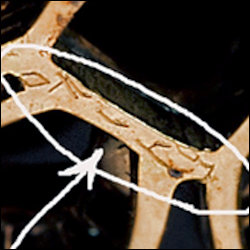

Marks – Stock number (1.), Gold Standard (2.), Workmaster Hallmarks (3.):

- Stock number – Only two of the objects (B.-C.) are inscribed with the identical Fabergé stock number 54140, yet all three brooches are credited to the August Holmström workshop (active 1857-1903).

Does a piece of jewelry a mere 2 1/8 inches (5.5 cm) long usually have multiple hallmarks as seen in the photographs on the Romanov Russia website? The stock number 54140 is shown three (3) times in a total of five (5) marks on the pendant-brooch, and a Fabergé invoice has not been found in the Russian Archives (RGIA) by our Russian research colleagues, nor is it cited by auction houses or dealers.

Three scratched stock numbers shown in (B.) Original Fabergé scratched inventory number 54140 on the back on the gold frame.

Three scratched stock numbers shown in (B.) Original Fabergé scratched inventory number 54140 on the back on the gold frame.

The top rim of the gold frame is marked with St. Petersburg arms and scratched inventory number 54140.

Fabergé’s scratched inventory number 54140 on the back of the heart pendant.

(Courtesy Romanov Russia) - Gold Standard – Marked on the pin guard with 56 zolotniks, Russian gold standard equivalent to 14K-583 (Ed. note: 14K gold contains 58.3% pure gold, or 583 grams per thousand) and St. Petersburg coat-of-arms. All three descriptions match on the gold standard.

The McFerrin brooch (C.) on exhibit until March 2013,

The McFerrin brooch (C.) on exhibit until March 2013,

and detailed close-ups are not available at press time. - Workmaster Marks – The various dates of the three brooches from the published literature (1880’s, ca. 1897, ca. 1900 and later changed to 1895) match the active dates of August Holmström (born 1829-1903) and his marks mark AH

– active 1857-1903. However, a small deviation of a dot between the A and H needs further study. Could it be an August Hollming – workmaster mark A*H

– active 1857-1903. However, a small deviation of a dot between the A and H needs further study. Could it be an August Hollming – workmaster mark A*H  – active 1880-1913? The suggested Holmström marks from a 2021 auction compared to (B.) and (C.) show other deviations, i.e., the location of the hole in the letter A, and a dot between the A and H? There is no mark illustration known from brooch (A.) at the Bukowskis auction in 2011. This same conundrum, not yet solved, occurred in another study, “Variations on a Theme: Fabergé’s Sunburst Enameled Cigarette Cases” published in the Fabergé Research Newsletter, Summer 2020.

– active 1880-1913? The suggested Holmström marks from a 2021 auction compared to (B.) and (C.) show other deviations, i.e., the location of the hole in the letter A, and a dot between the A and H? There is no mark illustration known from brooch (A.) at the Bukowskis auction in 2011. This same conundrum, not yet solved, occurred in another study, “Variations on a Theme: Fabergé’s Sunburst Enameled Cigarette Cases” published in the Fabergé Research Newsletter, Summer 2020.

Examples of similar recent marks:

(D.) Brooch

(D.) Brooch

(Sotheby’s London, June 2, 2021, Lot 64) (D.) Brooch

(D.) Brooch

(Sotheby’s London, June 2, 2021, Lot 22) (B.) Pendant-Brooch

(B.) Pendant-Brooch

(Romanov Russia) (C.) Brooch

(C.) Brooch

(McFerrin Collection)

Provenance – Two Internet resources and one Russian monograph point to Empress Maria Feodorovna as the original owner of diamond bow brooch. A jewel album with color illustrations and object descriptions just for the Empress similar to the albums for her son, Emperor Nicholas II3, and her daughter, Grand-Duchess Xenia4, are not known to scholars. In a 2002 essay, Alexander Sokolov5 briefly summarizes “the 6.5 million documents and objects on more than 86 kilometers of shelves” available for research in the Russian State Historical Archives (RGIA).

Internet sources:

- A Pinterest article shows a brooch photograph from the Romanov Russia website (with the brooch dated ca. 1897) with an autographed 1885 photograph of Maria Feodorovna and an 1896 sketch, all without citations or a credit source. The authors of this essay later discovered this is not a match.

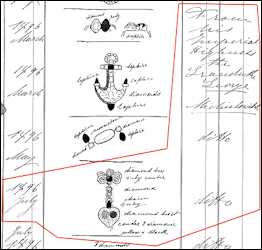

- Joanna Wrangham on her Winter Palace Research website (July 24, 2018) shows only 14 out of 30 pages from the Jewel Album of Empress Maria Feodorovna with this summary text: “The Jewel Album’s front page has the inscription ‘Alexandria 1894 Maria’ in Empress Maria Feodorovna’s handwriting. In the summer of 1894, a lady-in-waiting started drawing the empress’ jewels. Later in the winter of 1894-1895 after the death of Alexander III, Empress Maria began writing their descriptions in the columns.” (Ed. note: The date of the brooch in the study falls after the selection of pages uploaded on this website.)

- The Russian hard copy reference book by Zimin, Igor Viktorovich, and Alexander Rostislavovich Sokolov, Jewelry Treasures of the Russian Imperial Court [ювелирные сокровища российского императорского двора], 2013, 766 pages (E. 1) contains these segments:

- Jewelry Collection of Empress Maria Feodorovna (Ювелирная коллекция императрицы Марии Федоровны), pp. 472+

- Jewelry Album of Empress Maria Feodorovna (Ювелирный альбом императрицы Марии Федоровны), pp. 532+

- Appendix 3, Maria Feodorovna’s Jewelry Album (Приложение 3, Ювелирный альбом Марии Федоровны), pp. 657+ (E. 3)

- Drawing of Brooch with the Heart, p. 684.

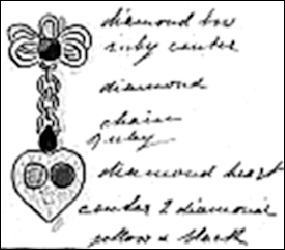

Riana Benko discovered in the Zimin/Sokolov text (Appendix 3, p. 684) a drawing (E. 2) which is an exact match to the diamond bow brooch in our study. Was the mystery of the presenter and the recipient solved for one and/or possibly all three brooches? In the opinion of the authors the internet sources cited above (#1 and #2) do not apply.

R. Sokolov, Jewelry Treasures of

the Russian Imperial Court

[ювелирные сокровища

российского императорского

двора], 2013. In Russian.

His Imperial Highness the Grandduke George

Michielowitch – ditto’ (Ibid., p. 684)

(2013): “Brooch by Fabergé,

Workmaster August

Holmström, St. Petersburg,

ca. 1900. Diamond-set

Jeweled Brooch.

chain / ruby / diamond heart / center 2 diamonds /

yellow and black”

(Zimin/Sokolov, p. 684)

Russia and Princess Marie

of Greece and Denmark

(C Boehringer, Public domain,

via Wikimedia Commons)

The findings of the research quartet for a more correct identification of one brooch (C.) documented three times in a variety of ways without archival details between 2011-2016, and now in the McFerrin Collection in Houston, Texas are – the brooch was a gift in 1896 by the Grand Duke George Mikhailovich (1863-1919), and has no connection to the Empress Maria Feodorovna. The Grand Duke’s name listed in column three of the handwritten inventory is recorded in two different handwritten scripts (E. 2 and E. 4). One caveat, we lack close-up photographs of the verso for the McFerrin brooch to examine and compare until after the Houston Museum of Natural Science venue closes in March 2023. Updated information: Newsletter readers have advised the family nickname for Grand Duchess was Minnie or Greek Minnie. Perhaps the confusion between the Empress Maria Feodorovna (Minnie) and the Grand Duchess Marie Georgievna (Greek Minnie) arose that way.

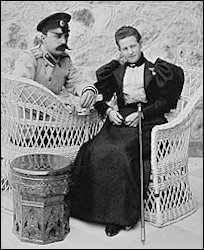

Timothy Adams discovered information about the lives of Princess Marie and the Grand Duke George Mikhailovich along with a photograph (E. 5) in which she is wearing a lapel watch. At first glance, Adams thought our elusive pendant-brooch given to Princess Maria of Greece and Denmark had been found. Even turned upside down, the object on her left shoulder and the 1894 date of the photograph are not matches to the 1896 gift discussed in this study.

James Hurtt with his vast knowledge of Russian history and the genealogy of the Imperial family added more substantial insights. The daughter of King George I of Greece, Princess Maria of Greece and Denmark (1876-1940) between 1889, or 1895 to 1900, became engaged to Grand Duke George Mikhailovich of Russia (1863-1919). She was the groom’s first cousin once removed, who courted her for five years. The groom gave her a heart-shaped pendant-brooch in July of 1896 possibly as an engagement gift, or a gift to mark her July 22nd name day, and many other gifts around the time of their marriage on the island of Corfu on May 12, 1900. The original cover of the jewel album has its title written in English – the language Princess Maria (after her marriage Grand Duchess Maria Georgievna of Russia) grew up speaking English even before learning Greek and Russian.

One must understand the familial connection between Empress Maria Feodorovna and Grand Duke George Mikhailovich (1863-1919), the person cited on the sketch inventory (Zimin/Sokolov, p. 684). He is a first cousin of Marie’s husband, Emperor Alexander III; in other words, he is a distant relative. Also, the date of 1896 July gift does not correspond to any significant anniversary for Maria Feodorovna (other than her name day which she shared with Princess Marie of Greece) given the expensive and rather personal nature of this pendant-brooch.

Workshop Puzzle – James Hurtt’s analysis of the Holmström and Hollming hallmarks suggests the brooch/pendant was made in the Holmström workshop:

- The marks appear closer to Holmström’s mark than Hollming’s despite the slight discrepancies.

- The date of July 1896 when Grand Duke George Mikhailovich presented the jewel to Princess Maria coincides with the April date when the princess accepted Grand Duke’s proposal.

- In April of 1896, the Fabergé workshops were in a feverish pitch to finish all of the orders the Cabinet and the Imperial Family had initiated in connection with the coronation of Emperor Nicholas. At the end of May 1896, Hollming studio was so overwhelmed with the production of presentation cigarette cases that the Holmström’s workshop staff assisted in fulfilling orders.

- Hollming made jewelry but mostly modest pieces, not a large and important piece like the diamond brooch with two significant diamonds which most likely came from the Holmström’s atelier, and was commissioned or chosen from stock by Grand Duke George Mikhailovich.

- The inventory number seems to align with other pieces of jewelry from 1896.

Extant Fabergé objects with original provenances of Grand Duke George Mikhailovich (1863-1919) and Grand Duchess Marie Georgievna (1876-1940) have been on the auction market recently:

- Doyle, New York. English & Continental Furniture/Old Masters/Russian Works of Art, Jan 31, 2018, Lots 103-134 from the descendants of Grand Duke George Mikhailovich.

- Sotheby’s, London. Russian Works of Art, June 9, 2021, Lots 41-42, 61-62, 68 from Grand Duke George Mikhailovich (1863-1919) and Grand Duchess Marie Georgievna (1876-1940).

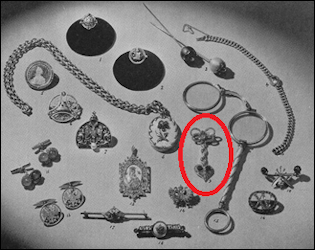

Readers fascinated by research might enjoy studying the auction links to discover other historical matches for possible Fabergé objects by using the extensive Zimin/Sokolov lists, and also unraveling the details for a similar pendant brooch from Hammer Galleries sales catalog. Is there connection, and can the provenance of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna to this Fabergé item really be proven?

(Hammer Galleries, Sales Catalog, ca. 1939, Jewelry Section, #9)

| 1 | Fabergé: The McFerrin Collection – The Opulence Continues… 2016, p. 86. |

| 2 | Everyday Fabergé: The McFerrin Collection (Exhibition). |

| 3 | Jewelry Album of Nicholas II by Igor Viktorovich Zimin; “Jewel Album of Tsar Nicholas II: Research Updated” discussed in Fabergé Research Newsletter, Fall and Winter 2019. |

| 4 | Ksenia (Xenia) Alexandrovna, Grand Duchess of Russia (April 6, 1875 – April 20, 1960) PERSONAL ILLUSTRATED INVENTORIES OF JEWELLERY AND BIBELOTS FROM 24TH JUNE 1880 TO 1905, AND OF JEWELLERY FROM 12 JANUARY 1894 TO 25 MARCH 1912, IN TWO VOLUMES offered at Bonhams, London, November 30, 2011, Lot 155. |

| 5 | Krog, Ole V., Maria Feodorovna Empress of Russia: An Exhibition about the Danish Princess Who Became Empress of Russia, 1997, pp. 352-360. |

The Art Nouveau movement popular between 1890 and 1910 with its emphasis on organic forms and asymmetrical designs attempted to break away from the staid and academically formal styles seen in 19th century classicism. Flowers and vines with sensuous undulating lines, curling waves and ripples upon water inspired the modern artist to seek new forms of expression in painting, architecture, furniture, jewelry, and glasswork. The popularity of the Art Nouveau style in St. Petersburg and the artistry of the Fabergé firm combined with the top glass makers in the field supplied members of the Imperial family and the nobility of the times with beautifully enhanced vases. Among the glass makers were the American Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848-1933), the Loetz Company in Bohemia (ca. 1849-1947), and two French artists, Émile Gallé (1846-1904) and René Lalique (1860-1945). The Russian jeweler, Carl Fabergé (1846-1920), sent his gifted stone carver and modeler Peter Derbyshev (1888-1914) to study under Lalique in Paris. Unfortunately, he returned to his native country only to die in the early years of World War I. Three glass vases in the McFerrin Collection on view1 at the Houston Museum of Natural Science in Texas exhibit Fabergé metal bases inspired by the Art Nouveau theme of the vase’s decoration:

- Vase with peacock-feathers and a Fabergé silver peacock base (A.),

- Water-like undulating lines accented with silver-gilt dolphins and waves by Fabergé on a vase converted into a lamp (B.), and

- Floral-patterned vase supported with Fabergé silver leaves. (C.)

Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848-1933) instead of joining Tiffany & Co, his father’s jewelry firm, chose to pursue his creative passions in the decorative arts with leaded glass, bronze casting and interior design. His Tiffany Studios creating lamps, stained glass windows, and vases with organic and nature themes was started in Corona Queens, New York, with financial help from his father, Charles Lewis Tiffany (1812-1902). At the 1900 World Exposition in Paris, the son’s Tiffany enterprise won a grand prize for its iridescent Favrile glass (from the Old English word fabrile meaning hand-wrought). Louis and his English partner Arthur Nash melted together different colors ingraining them into the glass, and not just applying them to the surface. The iridescent glass vase (A.) in the McFerrin Collection rests in a peacock base designed by Fabergé workmaster Viktor Aarne ![]() (active 1891-1904) in which peacocks are prostrate on the ground with their tails proudly supporting the vase with its colorful glass feathers.

(active 1891-1904) in which peacocks are prostrate on the ground with their tails proudly supporting the vase with its colorful glass feathers.

Complete with Silver Base in the Form of Three Peacocks from the Fabergé Studio of Viktor

Aarne

Mikhail Cantacuzène (1875-1955) and His Bride, Julia Dent Grant (1876-1975),

Grand-daughter of the American President, Ulysses S. Grant.

Signature and Tiffany Stock Number 07233.

(In Situ Photograph Patricia Hazlett,

Photographs Courtesy McFerrin Collection)

Later Princess Cantacuzène,

Countess Spéransky (by Marriage)

(Unknown author, Public domain,

via Wikimedia Commons)

Peacock Vase History:

The descriptive text in the auction catalog (Sotheby’s London, November 10, 1970, Lot 78) suggests “The base signed in full Louis C. Tiffany and numbered 07233…The prefix ‘0’ to the numbering indicates a special order. Given by L.C. Tiffany at the wedding from the White House of the present owner’s grandmother, Miss Julia Grant, to Prince Michael Cantacuzène. The vase was taken with other Tiffany pieces to their home in Russia, where Fabergé was commissioned to make the mount.” To verify the provenance details cited in the auction catalog the authors reviewed the online version of the bride’s 1922 autobiography, My Life Here and There2. There is no mention of the vase nor the White House connection to it. The bride describes her two wedding ceremonies – “The Russian ceremony was to be performed first, and (by special dispensation) at home, the priests coming from New York and bringing all the necessary paraphernalia with them”, and on the next day, “At the American chapel, also, the wedding was a very pretty one; as simply carried out as possible, according to our wish, for Cantacuzène and I disliked extremely the idea of exaggeration or show.” According to the New York Times3, “The couple married at Beaulieu, an Astor home which her aunt, Bertha Palmer, had leased for the summer season in Newport, Rhode Island, in a small, private Russian Orthodox ceremony the evening of 24 September 1899. The following day at noon there was an Episcopal Church wedding service in All Saints’ Memorial Chapel, Newport.” They journeyed to St. Petersburg, Russia, and lived there until the 1917 Revolution when they escaped and settled in Washington (DC) for a few years, then moved to Sarasota, Florida, and were divorced in 1934.

The vase sold at the 1970 Sotheby’s London auction for £1450, and was featured regularly by the London jewelry dealer Wartski during that decade:

- 1971 Wartski advertisements – Connoisseur, Vol. 176, no. 707, January 1971:1 (ad pages); Apollo, January 1971:55 (ad pages); Auction (Parke-Bernet), Vol. 4, no. 5, January 1971:62.4

- 1977 Snowman, A. Kenneth. Fabergé 1846-1920, 1977, p. 127, S1. Blockbuster Fabergé exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum, object lent by Herr A.F. Harmstorf, Hamburg, Germany, who appears to be affiliated with the German shipping company of the same name.

- 1979 Snowman, A. Kenneth. Carl Fabergé, Goldsmith to the Imperial Court of Russia, 1979, pp. 62-63. The Provenance detail from the 1970 the auction catalog is mentioned in the entire decade of advertisements, never appears again.

- In what collection was the vase from 1979 to 2014?

- 35 years later the vase sold at auction – Christie’s London, November 23, 2014, Lot 203, via the dealer John Atzbach to the McFerrin Collection. Since then, it has been shown in four venues at the Houston Museum of Natural Science, and can be viewed there until March 2023. Published in Fabergé: The McFerrin Collection – The Opulence Continues… 2016, p. 140.

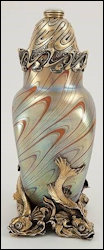

A second Tiffany vase (B.) in the McFerrin Collection is mounted with dolphins by Viktor Aarne ![]() (active 1891-1904), and was converted into an electric lamp. Electricity was introduced to Russia in the early 1880’s:

(active 1891-1904), and was converted into an electric lamp. Electricity was introduced to Russia in the early 1880’s:

- The first electric street lights were installed at Gatchina Palace in 1881.

- St. Isaac’s Cathedral was illuminated with incandescent lamps in 1882.

- In 1883, the Nevsky Prospect was illuminated.

- 1886 saw the formation of the first electric company in St. Petersburg.

- However, there was no real domestic consumption of electricity until 1890.5

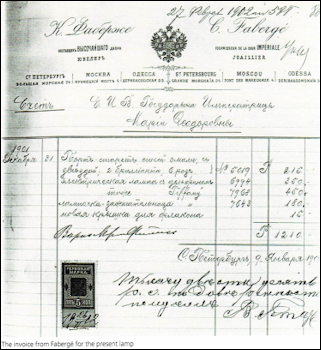

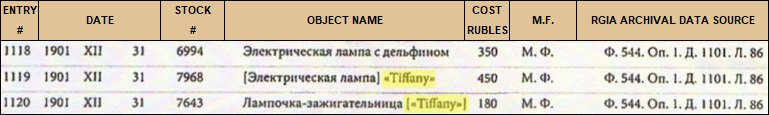

Offered at auctions in 1966, 1968, and again in the year 2014 when an original Fabergé invoice was found with a scratched stock number 7968. Over the years auction text descriptions state as yet unconfirmed and possibly incorrect details. The authors’ research could not confirm:

- the body of vase/converted lamp hails from the glass maker, Loetz Company in Bohemia (ca. 1849-1947),

- if the dolphin mount was made by the Fabergé workmaster, Julius Alexandrovich Rappoport [

, active 1883-1908],

, active 1883-1908], - a lamp was purchased for the Imperial yacht, Standart, launched in 1895. Mark Moehrke, Vice-President/Director, Russian Works of Art, Doyle Auctions, prior to 2016 studied extant Standart interior photographs without finding this particular lamp.

St. Petersburg, 1899-1904, Scratched Inventory Number 7968. Glass: Unmarked, Attributed to Loetz6.

Provenance: The Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna, Purchased from Fabergé’s St. Petersburg Shop on December 31, 1901 for 450 Rubles.

(Presented by Mark Moehrke, Doyle Auction in “The Wonder of Fabergé: A Study of the McFerrin Collection” at the 2016 Houston Fabergé Symposium.)

Converted Lamp

(Photograph McFerrin Collection)

2014, Lot 204, invoice in hard copy catalog only, not on the Internet)

Translated Invoice Text: Electric lamp with dolphins # 6994 350

rubles | same “Tiffany” #7968 450 rubles | Light Fixture

(Conversion?) [“Tiffany”] #7643 180 rubles

(Guzanov, A., and R. R. Gafifulin, Fabergé Items of Late XIX – Early XX Century in the Collection of the State Museum of Pavlovsk, 2013, Appendix, p. 114)

Translated Invoice Text: #6694 Electric Lamp with dolphin 350 rubles | #7968 [Electric Lamp] “Tiffany” 450 rubles | #7643 Light Fixture (Conversion?) [“Tiffany”] 180 rubles

Revised Dolphin Vase History:

- December 31, 1901 Purchased by Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna from the Fabergé firm. (In a 2014 compilation of archival documents identified as a Tiffany Vase purchased by the Empress from Fabergé, details published in Guzanov, A., and R. R. Gafifulin, 2013, Appendix, p. 114. In Russian.)

- January 9, 1902 Fabergé invoice with Tiffany note (First published in the Christie’s London, November 24, 2013, Lot 204, invoice in hard copy auction catalog only, not on the Internet, attributed to Loetz).

- 1966 Sotheby’s London, March 21, 1966, Lot 120, final bid £320 to Eriksohn (catalog text: Loetz glass with a different Fabergé workmaster Julius Alexandrovich Rappoport [

, active 1883-1908], from the Tsar’s yacht, Standart)

, active 1883-1908], from the Tsar’s yacht, Standart) - 1968 Sotheby’s London, December 9, 1968, Lot 156, final bid £1200 to Wartski (same catalog text as in 1966 entry above)

- 1969 and 1973 Wartski, London (Ad). “Royal Lamp by Carl Fabergé”, Connoisseur, vol. 170, no. 686, April 1969:1 (ad pages); Apollo, January 1973:73 (ad pages); Connoisseur, January 1973:33 (ad pages).

- 1977 Snowman, A. Kenneth. Fabergé 1846-1920, 1977, p. 127, S2. Viktor Aarne

(active 1891-1904) noted as the mark. Loetz glass. Blockbuster Fabergé exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum, object lent by Herr A.F. Harmstorf, Hamburg, Germany, who appears to be affiliated with the German shipping company of the same name.

(active 1891-1904) noted as the mark. Loetz glass. Blockbuster Fabergé exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum, object lent by Herr A.F. Harmstorf, Hamburg, Germany, who appears to be affiliated with the German shipping company of the same name. - 1979 Snowman, A. Kenneth. Carl Fabergé, Goldsmith to the Imperial Court of Russia, 1979, pp. 62-63. Loetz glass without provenance.

- In what collection was the vase from 1979 to 2014?

- 35 years later the vase/lamp reappeared at auction – Christie’s London, November 23, 2014, Lot 204, Loetz glass, via the dealer John Atzbach to the McFerrin Collection and since then shown in four venues at the Houston Museum of Natural Science until March 2023. The scratched stock number 7968 published for the first time. Marked with Viktor Aarne

(active 1891-1904) under the base and on upper wavy mount.

(active 1891-1904) under the base and on upper wavy mount. - 2013 Guzanov, A., and R. R. Gafifulin, Fabergé Items of Late XIX – Early XX Century in the Collection of the State Museum of Pavlovsk, Appendix, p. 114, identified as Tiffany.

- Fabergé: The McFerrin Collection – The Opulence Continues… 2016, p. 141. Object appears in the Tiffany Art Glass section but is identified as Loetz glass based on the Christie’s auction lot description which contains for the first time a published invoice with the Tiffany information, and is confirmed by the 2013 Guzanov and Gafifulin research.

Since the lamp fixture covers most of the vase’s bottom where the workmaster mark of a glass vase is usually found, the signature has been difficult to confirm. Was the mark destroyed when the hole for the electrical wiring was made? In the Fabergé literature for 50 years (1966-2016) the lamp vase has been assumed to be Loetz glass. Fortunately, the original Fabergé invoice (reproduction only in the hard copy auction catalog, Christie’s London, November 24, 2014, Lot 204), and the listing of the stock number 7968 in the Maria Feodorovra’s 1901 compilation of invoices8 confirm the McFerrin art object is a Tiffany glass rather than Loetz. The details in the three line-items for electric lamps with dolphins and the name Tiffany in the 2013 Russian text by Guzanov and Gafifulin illustrated and translated into English under the illustration above suggest three Tiffany-related objects:

- #6694 Electric Lamp with dolphin 350 rubles

- #7968 [Electric Lamp] “Tiffany” 450 rubles (McFerrin Collection)

- #7643 Light Fixture (Conversion?) [“Tiffany”] 180 rubles.

Was there a pair of lamps? Is the second lamp extant and can the two lamps be compared at some point in the future? Another question, did Empress Maria Feodorovna (1847-1928) buy a Tiffany Art Nouveau object made into the lamp for the Imperial Yacht the Polar Star, one of her favorite yachts which went into service in March 1891. Her husband, Emperor Alexander III, died in 1894. The yacht later served the Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna, who used it annually to sail to Denmark and England.9 Stylistically, the two Tiffany vases with peacocks (A.) and dolphins (B.) Fabergé-mounts researched in this essay, and now in the McFerrin Collection, are a match. A peer reviewer of this essay wondered if the two Tiffany electric lamps stock #6694 and #7968, and a light fixture (conversion?) #7643 bought by Maria Feodorovna around Christmas or New Years may have been holiday gifts for family or friends, and not for herself?

Cameo Glass Vases

Etching and engraving glass into a raised pattern on the surface creates cameo glass. On the Mcferrin vase (C.) the green leaves and flowers were covered in acid-resistant wax. Once the acid is applied to the surface of the vase only the exposed areas are etched away, while the areas covered by the wax stay raised on the glass surface. The leaf and flower details are then enhanced by small cutting wheels and engraving tools to bring out the fine details. Over-laying one color of glass on another, then etching or cutting through the top layer allows for a different color background giving depth to the pattern. Fabergé captures the essence of the vase design with a metal base mimicking the undulating branches and leaves.

Glass Factory, ca. 1896-1908, mounted on a

silver vine and leaf base with a Fabergé

stamp and Imperial Warrant from the

Moscow workshops.

(Christie’s New York, April 23, 2010, Lot 93,

no longer on the Internet; McFerrin, Dorothy.

From a Snowflake to an Iceberg:

The McFerrin Collection, 2013, p. 33)

(overlay) vase with leaf and twig mounts, and

a silver matching leaf base base enhancement

is one of three Gallé vases decorated by

Fabergé workmaster Julius Rappoport,

(active 1883-1908) for which archival data is

extant. All three vases with their interesting

histories were made before 1899, and are

marked on the silver bases…10

The French firm of Gallé was one of the foremost cameo glass artisans in the Art Nouveau period. A pink and black Gallé vase (D.) in the Hermitage Museum Collection, St. Petersburg, Russia, has a similar silver mounting to the McFerrin Collection vase made by Fabergé workmaster Julius Rappoport, ![]() (active 1883-1908) in St. Petersburg. The black glass surface on the vase was etched away to expose the previous layer of pink glass. The color can be varied in subtle ways depending on how deeply one cuts into the glass, thus allowing for gradations and areas of lighter or darker colors.

(active 1883-1908) in St. Petersburg. The black glass surface on the vase was etched away to expose the previous layer of pink glass. The color can be varied in subtle ways depending on how deeply one cuts into the glass, thus allowing for gradations and areas of lighter or darker colors.

The Art Nouveau movement which began in France made a lasting impression on the world of the art. Its influence on the decorative arts is seen in the work of the American glass maker Tiffany and together with Carl Fabergé, the Russian court jeweler. By the mid-1920s the Art Deco movement over-shadowed it, even though the impression the Art Nouveau era made in just two decades created a lasting impact on the art world. The Fabergé-mounted glass vases and lamp in the McFerrin Collection are an unwavering testimony to the enduring inspiration of this fascinating art history period. And thanks to the continued discovery of original source documents, researchers can confirm or dispel assumptions about these objects. Scholars constantly seek the truth to see the past more clearly, and to learn from it.

| 1 | Everyday Fabergé: the McFerrin Collection, April 2, 2021 – March 2023. |

| 2 | Princess Cantacuzène, Countess Spéransky, Née Grant, 1922, pp. 201-205. |

| 3 | “Miss Julia Grant Married: The Ceremony of the Russian Church performed at Beaulieu”, The New York Times, September 25, 1899, p. 7; “An American Princess: Public Wedding of Miss Julia Grant and Prince Cantacuzène”, The New York Times, September 26, 1899, p 6. |

| 4 | McCanless, Christel Ludewig. Fabergé and His Works: An Annotated Bibliography of the First Century of His Art, 1994, #678-679. |

| 5 | Hurtt, James. “Cutting the Cord: An Exploration of Fabergé’s Mechanical Bell Pushes”, Fabergé Research Newsletter, Fall and Winter 2018. |

| 6 | Loetz Identifying Website |

| 7 | McCanless, Christel Ludewig. Fabergé and His Works: An Annotated Bibliography of the First Century of His Art, 1994, #629. |

| 8 | Guzanov, A., and R. R. Gafifulin, Fabergé Items of Late XIX – Early XX Century in the Collection of the State Museum of Pavlovsk, 2013, Appendix, p. 114. |

| 9 | The Fates of the Russian Imperial Yachts ‘Standart’ and ‘Polar Star’ by Paul Gilbert, October 21, 2019. |

| 10 | Hurtt, James. “Faberge Vases Galore – In Search of Historic Truth”. Fabergé Research Newsletter, Spring and Summer 2021 |

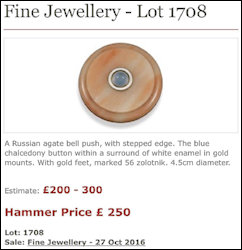

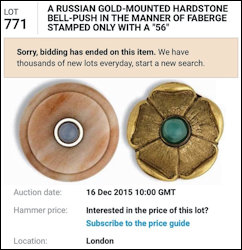

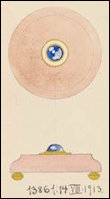

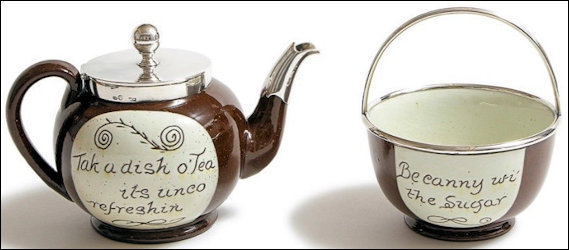

Fabergé objects have fascinated me for many years. I have searched far and wide for affordable examples of his oeuvre. Armed with knowledge gained from pouring over books (being a physician and professor that is something I am used to!), I have stumbled upon several treasures by sheer luck. A few years ago, while researching bell pushes (my favorite objet de vertu), I came across an article on Fabergé bell pushes by James Hurtt in an issue of The Magazine Antiques.1 The author had included an illustration of bell push designs by Henrik Wigström, Fabergé’s leading workmaster (H.W. ![]() – active 1903-1917) from a book of Wigström design drawings2, and objects for the years 1911-1916 (with the majority for years 1911-1913) also published in 2000. Immediately, I recognized a bell push I had previously seen online – a round stepped peach-colored hardstone base with three gold feet and a moonstone push button surrounded by a band of white enamel. Sold at a Wooley & Wallis (UK) in 2016 for £2503, it was simply defined as a Russian agate bell push (A.) with a 56 zolotnik mark, the Russian metal standard for gold. My research revealed the piece (B.) had sold a year earlier in 2015 at Christie’s South Kensington (UK), Interiors Sale4, not identified as Fabergé and bundled with another bell push.

– active 1903-1917) from a book of Wigström design drawings2, and objects for the years 1911-1916 (with the majority for years 1911-1913) also published in 2000. Immediately, I recognized a bell push I had previously seen online – a round stepped peach-colored hardstone base with three gold feet and a moonstone push button surrounded by a band of white enamel. Sold at a Wooley & Wallis (UK) in 2016 for £2503, it was simply defined as a Russian agate bell push (A.) with a 56 zolotnik mark, the Russian metal standard for gold. My research revealed the piece (B.) had sold a year earlier in 2015 at Christie’s South Kensington (UK), Interiors Sale4, not identified as Fabergé and bundled with another bell push.

October 27, 2016, Lot 1708.

December 16, 2015, Lot 771

With white enamel border around the chrysoprase button, on three gold cushion feet, the bakelite disc on base with inventory number L175F.”

(Description for Lot 771 – ABOVE RIGHT)

Based on the illustrations in the auction lots the object appeared to match the bell push depicted in the Wigström design drawings:

(Tillander-Godenhielm, Ulla, et al. Golden Years of Fabergé: Drawings and Objects from the Wigström Workshop, 2000, p. 128. Photographs Courtesy James Hurtt)

Having confidence in my diagnosis, I contacted the auctioneers to ask if the new owner would be willing to sell the bell push to me. The response was the owner would re-submit the object for a subsequent auction and I would be alerted. In the interim, I corresponded with the ever-helpful Kieran McCarthy at Wartski’s London about his opinion. His enthusiastic response was that I might be correct. Months passed and I finally received a notice about the new auction. On the day, I placed a bid and sat eagerly in front of the computer screen with my teenage son anticipating winning. Sadly, although an obscure item with just four bidders, I was underbidder by 100 Sterling pounds! Wartski’s had been the high bidder! No hard feelings, this is a hobby for me and a business for them. Friendship endures far beyond business. I feel vindicated that I was correct; the feet are plain as opposed to reeded in the illustration, but otherwise identical. Kieran later commented: “It reeks of Fabergé, so refined and stripped to the bare minimum of materials, the feel and balance is beautiful”. And I am very happy for James Hurtt, whose article provided the first clue in my treasure hunt. Eventually, he ended up as the new owner. Paulo Coehlo, the Brazilian novelist, said: “I can control my destiny, but not my fate.” I did my research and persevered but this bell push was not meant to be mine…

James Hurtt, a fellow Fabergé bell push enthusiast, shared additional background information with me:

Perseverance eventually pays off sometimes by utter chance. eBay is not usually the proper venue for authentic antiques, yet exceptions do occur! A couple of months after the auction for the aforementioned Fabergé item in searching the Internet I stumbled upon a fabulous bell push. The vendor was selling a huge collection of 55 bell pushes from an estate in Canada and there was a Prince among the paupers!! Selling a large collection on eBay over three nights the agent appeared to have no idea what he had…he basically started all objects at $49.95!

(Author’s Photographs)

This particular bell push was described as having a bronze base ‘with the number 5609’ and the mark of ‘a Viking ship’. The photograph shows the ‘5609’ is actually a ‘56’ zolotnik and the left-looking kokoshnik!5 The Viking ship is the rubbed maker’s mark. Well, as luck would have it, the bidding was a frenzy: a total of two bidders! I guess being in Canada and displaying on local eBay with no international viewing worked against the vendor! All bell pushes were sold for either the starting bid, or in my case, 2.5 times that amount! It was not someone pawning off reproductions, he was genuinely ignorant. A few weeks later safely in my hands, I commenced to take my purchase apart. The body, not just the base, was solid 14k gold (I had it acid-tested) which was quite a surprise. The quality of the enameling and the seed pearls are exquisite. I searched and found around 15 other similar-shaped Fabergé bell pushes. Despite no inventory number or legible maker’s mark I suspected it might be made by a Fabergé workmaster. James Hurtt and Kieran McCarthy are of the opinion it is by Ivan Savelevich Britzin, a Fabergé supplier. Born in 1870 at Chasovni in a Moscow province, he went to St. Petersburg at the turn of the 20th century, worked as an apprentice, and later qualified as a master. In 1910, he opened a workshop in Malaya Konyushenaya in St. Petersburg and occasionally supplied Fabergé with objects, since some pieces bear Fabergé’s mark as well as Britzin’s. He specialized in guilloche enamel objects in the Fabergé style.6

It is a beautiful piece and I will continue to research it. Sadly, the seller could not provide any provenance except that my bell push came from a Mid-western American collection. In this case, both destiny and fate were on my side…my bell had rung!

| 1 | Hurtt, James. “Fabergé Bell Pushes,” Magazine Antiques, October 2000, pp. 554-561. |

| 2 | Tillander-Godenhielm, Ulla, et al. Golden Years of Fabergé: Drawings and Objects from the Wigström Workshop, 2000. |

| 3 | Wooley & Wallis, October 27, 2016, Lot 1708. |

| 4 | Christie’s South Kensington, Sale 12017, December 16, 2015, Lot 771. |

| 5 | After 1899 a uniform mark was adopted throughout Russia. The traditional woman’s headdress, the kokoshnik, was introduced. For the years to 1908, the head faces to the left, and from 1908, to the right. |

| 6 | Lowes, Will, and Christel Ludewig McCanless. Fabergé Eggs: A Retrospective Encyclopedia, 2001, pp. 189-190. |

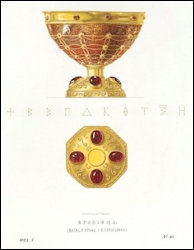

Fabergé workmasters – Erik Kollin (active 1870-1901), Henrik Wigström (active 1903-1917), and Fedor Afanas’ev (active 1907-1917) created Byzantine-style cups which closely resemblance each other, and the Byzantine cup (A.) in the Diamond Treasury, Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia. The Fabergé cups were inspired by an 1840 drawing (B.) done by a Russian painter and historian of art, Feodor Solntsev (1801-1892). Fabergé scholar Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm explained the origins of the beautiful drawing to me and stated it was originally in the collection of the noble Stroganov family. The artist’s commissions are exact drawings serving as an inventory of art objects in various materials, sacral objects, ceremonial armors, weapons and textiles, and more, found in imperial, princely, church, monastery collections. Solntsev made more than 3000 highly detailed drawing of different artifacts including the record of all the Kremlin’s riches. Of those drawings seven hundred are the core for the six-volume publications, Antiquities of the Russian State (1849-1853).1

with 13th Century Russian Gold, Garnet, Filigree

Additions in the Hermitage Diamond Room #124

(Courtesy State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia)

ca. 1840

(The Picture Art Collection/Alamy

Stock Photograph)

Carved gemstone cups from the Byzantine Empire (476-1453) were objects prized and sought after in western Europe. The late 10th century cup in the Hermitage is mounted with gold and gemstones in the early Kievan Rus style from 13th century Russia. Engraved into the jasper, and inlayed with gold wire, are the Greek letters and symbols: +ΒΒΠΔΚΘΤΣΗ, a cryptogram in which each letter stands for a word or name. Scholars debate the various interpretations, one of which is that the cup was a gift from the Byzantine Emperor Vasily II and Patriarch of Constantinople Nicholas II to Prince Vladimir of Kiev, who brought Christianity to Kievan Rus in the late 10th century. The cup was probably familiar to Carl Fabergé when he repaired and restored the ancient gold objects of the Hermitage, and later it served as the inspiration for several versions of his Byzantine-style cup produced by the Fabergé workshops. The basic style is the same, yet the materials are different.

Erik Kollin Workshop (Active 1870-1901)2

ca. 1880. Silver-gilt, Garnets, McFerrin Gallery,

Houston Museum of Natural Science, Texas, USA,

(McFerrin, Dorothy: From a Snowflake to an

Iceberg, 2013, p. 148)

Silver, Gold, Garnets, Unmarked, Collection of

Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

(Photograph Courtesy of Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm)

The earliest known Fabergé cup (C.) is made from carved agate, decorated with red faceted stones and cabochon-cut garnets on its base. It dates to ca. 1880, when archeological and historical revival items were in high demand. Kollin, who specialized in historical styles, was the perfect choice to execute this Byzantine-style cup. It was recently examined by Inda Immega, a professional mineralogist, who suggests the agate was mined in Brazil and the garnets are most likely from India. The bowl was possibly cut in Germany, where imported agates are used in lapidary work. The garnets are not from the Urals, as one would assume, but were purchased from a dealer in Indian gems.

These details add to our knowledge of how the Fabergé firm acquired materials and produced their stock. Another cup (D.) also of carved and polished agate is in style and material very close to the Kollin cup. It is unmarked but attributed to the Fabergé firm.

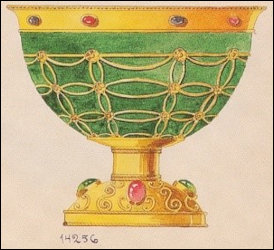

Henrik Wigström Workshop (Active 1903-1917)3

1908-17, Silver-gilt, Sapphires, Rubies, Height 3.5 in.

(Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, USA)

(Tillander-Godenhielm, Ulla. Golden Years of Fabergé:

Drawings and Objects from the Wigström Workshop,

2000, pp. 122-123.)

Cost Code Numbers

(Adams, Timothy. “Fabergé Design Sketches and

What They Teach Us”, Fabergé Research Newsletter,

Fall and Winer 2018, Courtesy Wartski)

A variation on the theme of Byzantine-style cups, obviously inspired by the original Feodor Solntsev model is the Wigström cup (E.) with a wide-beaded band set with cabochon-cut sapphires and rubies, and a production drawing (F.), a record of all the objects produced by the studio.

The bottom rim of the cup (G.) reveals not one but two scratched numbers – 24782 is the Fabergé stock number, and 288Q NM is a stock number and cost code for the London based Fabergé dealer Wartski. In a conversation with Wartski’s Kieran McCarthy, he stated their number was from the mid-1920s, and is new information about the history of this cup. It was my delight to reveal these specifics during the 2018 Fabergé Symposium at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond.

Fedor Afanas’ev, Independent Supplier (Active ca. 1907-1918)4

St. Petersburg, ca. 1913 with Engraving.

Height 2.36 in. Silver-gilt, Sapphires

(Kazan Collection, Christie’s, London,

April 15, 1997, Lot 56)

Afanas’ev, St. Petersburg, 1908-1917.

Height 5.63 in. Silver-gilt, Amethysts

(Bruun Rasmussen, Copenhagen, Denmark,

June 8, 2018, Auction 879, Lot 1930)

Similar nephrite Byzantine-style cups have appeared on the auction market:

- Christie’s New York, Kazan Collection of Works of Art by Carl Fabergé, April 15, 1997, Lot 56 (H.), scratched stock number 23104, Russian engraving ‘1888 11 Sept[ember] 1913’, with sapphires (M.Y. Ghosn, Objets de Vertu par Fabergé, 1996, no. 65.) Marked workmaster Fedor Afanas’ev. Price realized $46,000. The Honorable William Kazan was born in Beirut, his family claims a connection with the former Khanate of Kazan in central Russia, he trained as a jeweler, became a distinguished diplomat, and collector of Fabergé and Islamic coins.

- Bruun Rasmussen, Copenhagen, Denmark, June 8, 2018, Auction 879, Lot 1930 (I.), with amethysts, unmarked, attributed to Fedor Afanas’ev, estimate 150,000-200,000 kr., did not sell.

- Jackson’s International Auctioneers and Appraisers, July 13-14, 2021, Lot 160, attributed to Fedor Afanas’ev, gemstones not identified and without a stated provenance, sold for $15,000, including buyer’s premium.

Solntsev’s drawings published ca. 1840 influenced a myriad of decorative art objects from goldwork to imperial porcelain factory pieces. Fabergé recognized quality design when he saw it and must have been impressed with the Byzantine-cup illustration. Tillander-Godenhielm mentioned when the trend for historical objects faded toward the end of the 19th century, unfinished pieces were picked up and completed later to be added to the regular stock. This could be a reason why different workshops produced the same type of object. Erik Kollin died in 1901. Wigström and Afanas’ev continued to produce these cups till at least 1913. The Afanas’ev nephrite cup (H.) has an engraved dedication on it.

The Byzantine Empire known for its vast wealth, and the luxury items acquired by patrons of the arts, attracted the finest craftsmen who created objects still venerated in museums around the world. The Fabergé cups inspired by the world of Byzantium, and exquisitely executed by Fabergé workmasters, remind us to remember our artistic heritage, and the cultures long gone.

| 1 | Feodor Solntsev (1801-1892) |

| 2 | Tillander-Godenhielm, Ulla. Fabergé: His Masters and Artisans, 2018, pp. 60-69 |

| 3 | Ibid., pp. 86-133. |

| 4 | Ibid., pp. 206-207. In 1905, Afanas’ev became a Master Goldsmith, opened his own independent shop, and started working with Fabergé around 1907. |

- Christie’s London: How to Clean Your Jewellery

Can you just soak your baubles in gin? Or should you buy an ultrasonic cleaner? Our jewelery specialists advise on the best ways to put the sparkle back into your gems. - How to Clean Your Treasured Fabergé Object by Mark Schaffer, director, A La Vieille Russie, New York City

The wide range of materials, styles, and construction represented in Fabergé’s artworks precludes simplistic guidelines. One wants objects to look their best, but a balance must be struck with the dictum to cause no harm. If there are any doubts or hesitations about a home treatment, one must absolutely consult a qualified conservator.

An initial question is, does the piece in fact need cleaning, or appear to be a shadow of what it was at birth? Many Fabergé works will not need much cleaning at all, but if the answer is clearly yes, then the next step depends on the type of object and material. The most common issue is the tarnishing of silver or gilded silver. A polishing cloth might do the trick in most cases, but one has to be careful not to ‘catch’ the cloth on a mount, or dislodge a gemstone. A mild silver polish can be used, often with a small brush or cotton swab, but only if one is already familiar with the strength of the agent on the particular material, and on its adjacent material. Furthermore, some tarnish is intentional for artistic effect, and too strong of a polishing agent can remove gilding from silver. The agent normally will not harm any adjacent enamel, but could affect wood. If an object is composed of multiple parts, it normally needs to be disassembled before any cleaning, so as not to get cleaning agent inside (think bellpush, clock, or photo frame). Sometimes plain old dirt is the culprit, and soap and water are the best solution, so long as it is applied with the same care as with other cleaning agents. Whatever approach one decides to take, it is important to work over a contained protected surface, in case one’s fingers become slippery or a gemstone unexpectedly dislodges. And when in doubt, once again, consult a trusted conservator. - Preserving Library and Archival Treasures by Rose Tozer, senior librarian, Liddicoat Gemological Library and Information Center, Carlsbad (CA)

There is a common misconception among library users and many researchers that books and manuscripts should be handled with gloves. Special libraries at Yale University (scroll down to gloves), the Shakespeare Folger Library (excellent video), and Stanford University have studied this issue and concluded handling print materials while wearing gloves can do more harm than good. Wearing gloves (cotton, nitrile or latex) reduces the tactile sense one needs in order to turn pages without bending or breaking the paper. The best practice is to have library users wash their hands before touching paper and to handle all paper delicately.

A lengthy article, Misperceptions about White Gloves by Cathleen A. Baker and Randy Silverman mentions wearing latex or nitrile gloves, if the paper or binding has mold but even so, the tactile sense is reduced. “If gloves need to be worn for the protection of staff and readers, the authors recommend a close-fitting, unpowdered, vinyl glove to avoid problem with latex allergies. Tactile sensations will be diminished, but when handling mold or very dirty material, health and safety issues must prevail. Finally, the authors caution whether wearing gloves or not, running fingers over manuscript or printed areas of the text can unnecessarily damage fragile paper, or flaking media (commonly associated with iron gall ink), raised impressions (such as intaglio prints), or friable media (including pastels).”

In addition to books, our library at the Gemological Institute of America (GIA) has a variety of metal and wood objects, such as diamond cutting tools. We handle these materials with either cotton or nitrile gloves. None of the books we currently own have metal fasteners. Pure noble metals are not reactive to skin oils or acids, however, the alloys mixed with metals may be reactive. If the object is not cleaned thoroughly after handling with bare hands, the oils or acids can cause problems by breaking down the surface with tarnish. If wood is not resin coated, these objects can absorb skin oils as well.

Non-porous gems, like diamond, ruby, and sapphire, and enameled objects in good condition, can be handled with bare hands without causing damage. Porous or organic gems, (i.e., turquoise, opal, pearl, coral and shell) are susceptible to damage from skin oils or perfumes. All gems are best handled with clean hands and wiped down with a damp soft cloth after use.

Proper care of paper, gem and jewelry objects today will ensure their survival for future generations to study and enjoy.

Information about Fabergé exhibitions (both permanent and temporary) as well as museums with collections available for in person visits, virtual visits, or just good old fashion research were published in the previous edition of the Fabergé Research Newsletter thanks to newsletter contributor, Riana Benko. Corrections, updates, or new finds, please share with Christel McCanless to be listed in future issues.

Fabergé eggs are always a popular topic around the annual Easter celebration and throughout the year:

- Faber, Toby. Become an Instant Expert on Fabergé Eggs, Fine Arts Society Lecture, March 26, 2021.

- Chuda, Nancy Gould. Secrets of the Fabergé Eggs, Town and Country Magazine, Jun 11, 2021.

- Romanov Royal Martyrs: What Silence Could Not Conceal, the monograph draws on letters, testimonies, diaries, memoirs, and other texts never before published in English to present a unique biography of Tsar Nicholas II and his family…Historians who worked on the project – Nicholas B.A. Nicholson, Helen Azar, and Helen Rappaport, all noted specialists in Romanov history. The book features a 56-page color photo insert. The acclaimed Russian artist Olga Shirnina colorized the high-quality images, which appear in print for the first time. (Book summary courtesy Amazon) Published by St. John the Forerunner Monastery, 2019, the book is accompanied by a 2020 video, Romanov Fabergé Eggs in which well-known Fabergé scholars and collectors share their thoughts.

- A golden oldie, Fabergé: Imperial Eggs, is a 1996 biographical history of the Fabergé firm narrated by Fabergé scholars active at the time.

- Robb Weller and Gary H. Grossman Productions for Arts & Entertainment Television Networks. Fabergé: Imperial Jeweler. New York, 1996. Video, also later issued with a new title, Fabulous World of Fabergé.

The New York Metropolitan Museum opening of the 1996 traveling Fabergé in America exhibition introduces this overview of the story about the Russian court jeweler, Peter Carl Fabergé (1846-1920). Historical footage combined with explanations by historian Peter Kurth and curator Dr. Géza von Habsburg (erroneously cited as Hapsburg), collectors Joan Rivers and John Traina, Margaret Kelly (Trombly) for The Forbes Magazine Collection, dealers Kenneth Snowman of Wartski’s in London, and Peter Schaffer of A La Vieille Russie in New York, and great granddaughter, Tatiana Fabergé, complete the narration. Photographs of all four sons of Fabergé and his wife Augusta illustrate the family story during the reign of Tsars Alexander III (1845-1893) and Nicholas II (1868-1918)…(Annotation from Audio-visuals on the Fabergé Research Site.)

Other resources useful in studying the history of Fabergé eggs:

- Imperial Egg Chronology on the Fabergé Research Site by Christel Ludewig McCanless (USA)

- Mieks Fabergé Eggs, a website maintained since 2008 by Annemiek Wintraecken (The Netherlands). The segment about movies relating to eggs is very informative and comprehensive.

- Fabergé Discoveries, the egg web page with a few broken links is of interest.

Jordanville, New York (USA) Russian History Museum

Interesting online presentations for Fabergé which explore the artistry and genius of the court jeweler to the tsars, as well as research about Romanov Russia. A full overview of their Fabergé-related research and presentations.

Lexington, Kentucky (USA) International Museum of the Horse. A brief video depicts a Fabergé punch bowl set.

An article with a video in The Sun (UK), April 20, 2021, details an episode of a BBC show in which auctioneer Charles Hanson discusses a rare find – A Bargain Hunt Expert Was Left Shocked to Find Rare Ornaments Worth Up to £500k Dumped in a Shoebox.

The Alexander Palace Time Machine Discussion Forum posted on its website a List of Imperial Jewels Found in Tobolsk 1933, “a small but critical fraction of the possessions of the Russian Imperial family in exile. The true story was well hidden, until the fall of Communism in Russia, and [the list was] published in 1996. Our thanks to Rob Moshein for transcribing the list as printed in ‘The Last Act of a Tragedy’ by V. V. Aleskeyev, Yekaterinburg, 1996.”

In a five-hour video conference on a YouTube entitled “Museum Libraries in Modern Society” hosted by the Moscow Kremlin Museum seven presentation relate to the contents of the Fabergé Family Archives donated in 2020 from the estate of Tatiana Fabergé (1930-2020), great-granddaughter of Carl Fabergé. In a previous issue of this newsletter the gift was announced In Memoriam Tributes – Part II. The other three presentations relate to the jewelry notebooks of Emperor Nicholas II and Empress Alexandra Fyodorovna held by the Moscow Kremlin Museum, the Henry Charles Bainbridge Archives at the Fabergé Museum in St. Petersburg, and the Lillian Thomas Pratt Archives at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond (USA).

Conference agenda:

The Moscow Kremlin State Historical and Cultural Museum and Heritage Site

MUSEUM LIBRARIES IN MODERN SOCIETY

Unique Private Funds in Museum Archival and Library Collections

Moderator – Svetlana Anatolievna KOSTANYAN, Head, Research & Reference Library of the Moscow Kremlin Museums

Dr. Andrei Leonidovich BATALOV, Deputy Director for Research, Moscow Kremlin Museums – Welcome Speech

Tatyana Nikolaevna MUNTIAN, Moscow Kremlin Museums – Tatiana Fyodorovna Fabergé, The Guardian of the Family Memory

Dr. Marina Kirovna PAVLOVICH, Moscow Kremlin Museums – The Fabergé Family Archive at the Moscow Kremlin Museums: Composition and Structure

Daria Alexandrovna GALKOVA, Anastasia Andreevna KOMOLOVA, Svetlana Anatolievna KOSTANYAN, Moscow Kremlin Museums – Special Features of the Book Collection of T. F. Fabergé

Irina Sergeevna PARMUZINA, Moscow Kremlin Museums – Photographs from the Archive of T. F. Fabergé

Moderator – Svetlana Anatolievna KOSTANYAN, Head, Research & Reference Library of the Moscow Kremlin Museums

Elena Victorovna ISAEVA, Moscow Kremlin Museums – Documents, Designs and Tools of F. Agathon Fabergé and His Workshop in the Fabergé Family Archive

Daria Alexandrovna GALKOVA, Anastasia Andreevna KOMOLOVA, Moscow Kremlin Museums – Handwritten Notes in Books from the Library of T. F. Fabergé as a Source of Fabergé Heritage Studies

Dmitry Yuryevich KRIVOSHEI, Independent Researcher, Moscow, Dr. Valentin Vasilyevich SKURLOV, Scientific Consultant of Christie’s Auction House, St. Petersburg – History of the Archive of T. F. Fabergé and Its Role in Modern Fabergé Studies

Irina Andreeva BOGATSKAYA, Moscow Kremlin Museums – Notebooks of Emperor Nicholas II and Empress Alexandra Fyodorovna with Jewellery Designs from the Collection of the Moscow Kremlin Museums

Mikhail Vladimirovich OVCHINNIKOV, Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg – The Henry Charles Bainbridge Archive at the Fabergé Museum

Courtney TKACZ, Archivist, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond – The Lillian Thomas Pratt Archives at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

Gorelik, Boris. “Old Friends and Partners: Allan Bowe as an Associate of Carl Fabergé”, Jewellery Studies: The Journal of the Society of Jewellery Historians, 2021/2, pp. 3-11. Author studied archival details contributed by Allan Bowe’s business acumen relating to the commercial success of the House of Fabergé from 1880s’ to 1890’s. (Courtesy Wendy Bonus, The Fabergé Connection: A Memoir of the Bowe Family, 2010)

Muntian, Tatiana N. Katalog vedushchikh iuvelirnykh firm XIX-XX: Firma K. Faberzhe, Works by Leading Jewellery Firms of the 19th and Early 20th Centuries: C. Fabergé (Произведения ведущих ювелирных фирм ХIХ – начала ХХ века: Фирма К. Фаберже) Moscow: Muzei Moskovskogo Kremlia, 2019. Kremlin Museums publish here for the first complete a hard copy catalog (except for picture frames) of its Fabergé collection, some of which have not been previously published…(Courtesy Bronze Horseman Books)

The annual Sinkankas Symposium sponsored by the Gemological Institute of America (GIA) is one of the most important gemological forums in the world. Experts in the fields of science, history, gemological industry, and marketing of gemstones share their latest research. Art historian and Fabergé enthusiast Timothy Adams’ talk centered on Agate and Chalcedony Objects by Fabergé. An article about carvings of the Dreher family associated with Carl Fabergé is included as a reprint. A PDF is available of the 2021 Seventeenth Annual Sinkankas Symposium Agate and Chalcedony.

Paul Gilbert, Chronology of Events in the Life and Reign of Emperor Nicholas II includes more than 170 events in the life and reign of Emperor Nicholas II from his birth in 1868 to his death and martyrdom in 1918, and more than a dozen links to articles, which will provide the reader with additional information and photographs.

Natalia N. Sapfirova, PhD candidate of the State Higher Educational Institution in Ivano-Frankovsk, Ukraine, and Secretary of the Charitable Organization, International Memorial Foundation of Joseph Marshak, defended her dissertation topic, the Marshak jewelry firm active in Kiev and Odessa for 40 years from 1878-1918. A. Kenneth Snowman in his 1953 book, The Art of Carl Fabergé (p. 123) identities the firm as one of more than a dozen “most original and enterprising” contemporary competitors of the C. Fabergé company.

Sapfirova’s blog summarizes the honors bestowed on Carl Fabergé (1846-1920) in the 20th century:

In 2015, the Carl Fabergé Memorial Foundation published the book, C. Fabergé and J. Marshak, co-authored by Tatiana Fabergé, Valentin Skurlov, and Natalia Sapfirova.

Cynthia Coleman Sparke in her Collecting Guides article, “Separating the Eggs”, writes “that it is possible to collect the iconic brand without spending a king’s ransom” while celebrating the 175th anniversary of Carl Fabergé’s birth and looking forward to a new exhibition (Victoria & Albert Museum opening on November 20, 2021), Antique Collecting (UK), May 2021, cover, pp. 16-20.

Unusual Fabergé Objets d’Art Recently on the Market:

Carl Fabergé, c.1900

Agate, Gold and Enamel

(Wartski, London)

(A La Vielle Russie, New York City)

Features Unique Bell Pushes and More

(Ruzhnikov Fine Art & Antiques, London)

On August 14, 2021, the first 13 historic rooms of the Alexander Palace Museum, the personal residence during Imperial Russia for Emperor Nicholas II and his wife, Alexandra Feodorovna, were opened for visitors. Restoration began in 2012, and gradually continued until 2015, when the palace was completely closed to visitors. The entire renovation cost ca. $30 million (Video and photographs, Courtesy Paul Gilbert). Executive Director Michael Perekrestov, Russia and curator Nick Nicholson, Russian History Museum in Jordanville (NY) chat about the recent restoration of the Alexander Palace.