Newsletter 2023 Summer

- Two Identical Carl Fabergé Plaster Busts by Josef Limburg (1874-1955) Are a Matched Pair!

- Fabergé Memorials Unveiled (1996-2022)

- Highlights from the Recently Discovered 1924 Goznak List of Fabergé Imperial Eggs

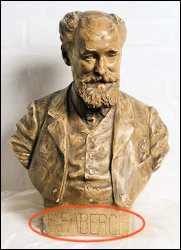

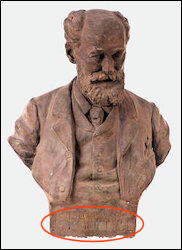

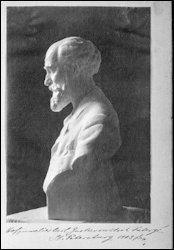

A well-known 1903 Fabergé bust (A.) with a gilded exterior willed by the late great-granddaughter Tatiana Fabergé (1930-2020) to the Kremlin Armoury Museum is identical to my 2023 discovery – dark gray-brown plaster Fabergé bust (B.) in the Stadtmuseum, Berlin, Germany, since 1971. Both busts have an engraved inscription, C. Fabergé, in the Latin alphabet on their pedestals.

(B.) Found in 2023! Carl Fabergé Bust, 1903, St. Petersburg. Plaster, shaded dark gray-brown, case cast as part of the composition, engraved [C. Fabergé in Latin Letters]

(SKU 71/25, 1971 Assession Number, Stiftung Stadtmuseum, Berlin, Reproduction: Oliver Ziebe, Berlin)

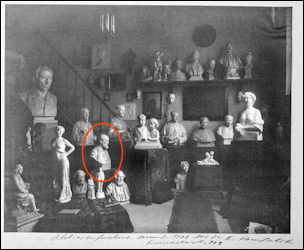

(C.) Limburg’s Handwritten Identification – “Studio photograph, December 1903, before the second Rome [Italy] trip, Eisenacherstr. 103.” Carl Fabergé (B.) and Grand Duke Boris Wladimirowitsch (see below G.) included. (Limburg Album, 2021, p. 39)

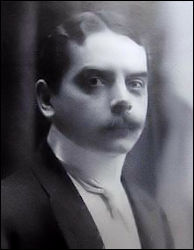

(D.) Josef Limburg (1874-1955) before 1912, German sculptor and medalist (Wikipedia and Munzinger Archive)

Another exciting research find are studio photographs (1903) with hand-written German captions in a photograph album which includes a hand-written German dedication (1906) on the album’s title page by the sculptor Josef Limburg (1874-1955) to his brother Carl Limburg:

Translation: Josef Limburg – An Album for Brother Carl [Limburg], reduced facsimile of the original (40x50cm), previously in private ownership, published by Werner Kurz with additions by Katharina Bott, Hanau, etc.

Title page inscription: “I dedicate to my dear Brother Carl this Album with Illustrations/of my best Works with Affection and Gratitude/Easter 1906/Jos. Limburg/60 Photographs of my Sculptures, many of them made in Marble, Bronze, Terra-cotta.”

The October 2021 publication of the Limburg Album (52 pages) was made possibe through the enthusiam and dedication of Werner Kurz (publisher), Katharina Bott (historian), and additional Limburg sculptor enthusiasts and collectors. And now in this newsletter essay – after a passage of 120 years since the studio photographs were taken – it is possible to present a selection of the photographs and chronological snapshots for two 1903 Fabergé busts created in the lost-wax technique (cire-perdue) by the German sculptor, Josef Limburg (born – 1874 in Hanau, 25 kilometers east of Frankfurt, Germany, died 1955 in Berlin).

Josef Limburg’s Fabergé Busts in Photographs from the Limburg Album (F.-H.):

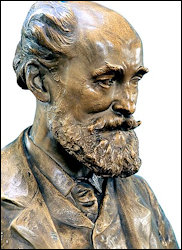

(F.) Limburg photograph of Carl Fabergé with sculptor’s handwritten identification – “Court Jeweler Carl Gustavowitsch Fabergé, St. Petersburg, 1903.” (Limburg Album, 2021, p. 45)

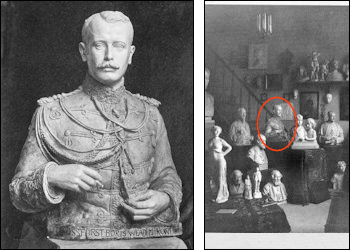

(G.) Grand Duke Boris Wladimirowitsch photographs with sculptor’s handwritten identification – “His Royal Highness Grand Duke Boris Wladimirowitsch, Tsarkoye Selo, 1903”. (Limburg Album, 2021, pp. 11, 24, 37 with side and frontal views, p. 39). [In October 1903, the Grand Duke enlisted in the Emperor’s retinue. On February 26, [1904], he left Russia for the Far East to take part in the Russo-Japanese War. (Wikipedia)]

(H.) Eugène Fabergé statuette with engraved Cyrillic inscription – Евгений Фаберже on the pedestal, St. Petersburg 1903, Berlin. Josef Limburg portrait of the gold and silver jeweler Eugène Fabergé (1874 – after 19552), plaster, yellow tint, 49.5 x 19 x 16 cm. [Statuette is depicted in Winter attire.] (SKU 71/35, 1971 Assession Number, Stiftung Stadtmuseum, Berlin, Reproduction: Gundula Ancke, Berlin; Text in Limburg Album, pp. 22 and 24.)

Chronological Snapshots

The 2021 Limburg Album with the 1903 archival photographs connects Carl Fabergé’s first son, Eugène Fabergé (1874-1960), to the sculptor of the two busts. Josef Limburg, also a son of a jeweler, began his education at age 16 in Hanau (his place of birth) at the Königliche Zeichenakademie, where drawing, modeling, and composition were taught.

- 1874 Carl Fabergé’s first son, Eugène Fabergé (1874-1960), and Josef Limburg, the sculptor of three Fabergé sculptures (A., B., H.) were born in the same year.

- October 21, 1892 Arrival Registration of Eugène Fabergé in Hanau, Germany

(Information and Photograph Courtesy Monika Rademacher, Stadtarchiv, Hanau, Germany, with Permission Code StadtA HU, C 2, 73)

(Information and Photograph Courtesy Monika Rademacher, Stadtarchiv, Hanau, Germany, with Permission Code StadtA HU, C 2, 73) - On December 4, 1892 Limburg founded with eight student-colleagues the Akademische Vereinigung Cellini (Academic Association Cellini) to support the friendship of former students at the Hanau Academy, among them probably Eugène Fabergé, who received a ‘commendation’ from the Academy’s internal competition in 1894.3

- 1892-94 Eugène Fabergé and Josef Limburg were students and friends at the Academy, even though Eugène returned to Russia the day Emperor Alexander III died (October 20, 1894, Old Style).

- 1902 Eugène Fabergé invited Josef Limburg to travel from Berlin to St. Petersburg, where Carl Fabergé4, his wife Augusta, and son Eugène (H.) posed as models for Limburg. It has been suggested Augusta Fabergé’s model was confiscated by the Bolsheviks in 1920, and is now lost.5

- 1903 Photographs of the St. Petersburg busts made and illustrated in the 1906 facsimile publication (cited in this research text as Limburg Album, 2021). The London Fabergé shop existed from 1903 until January 17, 1917.6

- 1906 Limburg Album in German dedicated to his brother (Carl Limburg), and a facsimile publication in October 2021 under the leadership of Werner Kurz (publisher) with extensive explanatory text by Katharina Bott (historian).7

- January 1921 “Eugène set up a jewelry business in Paris, France, with his brother Alexander … with limited success. The shop, Fabergé et Cie, closed when Eugène died in 1960″.8 The date of the bust’s transfer from the London shop to the Paris location is not known from the published literature.9

- 1923 Limburg bought a villa in Berlin-Lichterfelde where he lived until his death in 1955. It served as a memorial site for the German sculptor, until the villa in ca. 1965 was replaced with new housing. Both busts in this essay (B. and H.) were from 1957-1963 in Limburg‘s home and private studio with access to the public.10

- 1952-53 A. Kenneth Snowman, chairman of the British jewelry dealer Wartski, arranged the first Fabergé loan exhibition in 1949. In his 1953 book, The Art of Carl Fabergé, he details the history of the firm and provides technical descriptions of the objets de vertu. Eugène Fabergé wrote the 1952 Foreword for the book with a Paris location, and is credited as the owner of the bust modeled by Joseph (sic) Limburg.11 A revised and enlarged edition with new information and the Eugène Fabergé Foreword was published again in 1962 by Faber & Faber in the United Kingdom. All subsequent editions and impressions in the UK and USA are reprints of this edition, but without the Eugène Fabergé Foreword, since he had died in 1960.

- 1960 After Eugene’s death the gold plaster bust (A.) was given to Tatiana Fabergé, who worked in Switzerland, and lived in France. Did she loan the patina bust as a model (A.) for the Fabergé Heritage Collection bust (E.) shown on its 2018 website?

- 1971 Carl Fabergé-Bust (B.) and Eugène Fabergé statuette (H.) were donated by the Harriet Limburg Foundation12 together with 43 Limburg sculptures to the Berlin Museum, and in 1995 transferred to the Stadtmuseum, Berlin. Unfortunately, both the Fabergé busts and other prominent Limburg sculptures were not exhibited, while stored in the museum depository of 4.5 million objects.

- 2018 Bronze Fabergé bust matching the ‘patina’ model appears on the Fabergé Heritage Collection (E.) website.

- 2020 The well-known 1903 gold patina plaster bust (A.) along with her Fabergé family archives were willed to the Kremlin Armoury Museum in Moscow by the late great-granddaughter Tatiana Fabergé (1930-2020). An interview, “Treasure of the Fabergé Family: Archive of the Famous Jeweler Returned to Russia” with Tatiana Muntian, curator of the Carl Fabergé Collection at the Kremlin Armoury Museum, and the author of many scholarly books on the topic, is of interest. A five-hour video conference entitled “Museum Libraries in Modern Society” hosted by the Kremlin Armoury Museum explores in seven presentations the contents of the Tatiana Fabergé Family Archives donated in 2020.

| 1 | Fabergé, Tatiana F., Kohler, Eric-Alain, and Valentin V. Skurlov. Fabergé: A Comprehensive Reference Book, 2012, pp. 16, 216. |

| 2 | Eugène Fabergé died in 1960. Lowes, Will, and Christel Ludewig McCanless. Fabergé Eggs: A Retrospective Encyclopedia, 2001, p. 195. |

| 3 | Limburg Album, 2021, p. 24. |

| 4 | Limburg Album, 2021, p. 22, cites death date of Carl Faberge as 1925, should be 1920. |

| 5 | Information courtesy of Valentin Skurlov, not published in Fabergé, Tatiana F., Kohler, Eric-Alain, and Valentin V. Skurlov. Fabergé: A Comprehensive Reference Book, 2012, pp. 16, 216. |

| 6 | Lowes, Will, and Christel Ludewig McCanless. Fabergé Eggs: A Retrospective Encyclopedia, 2001, p. 197. |

| 7 | Limburg Album, 2021, p. 22, states the trip was before 1905. The Limburg photographs of Fabergé and Grand Duke Boris Wladimirowitsch sculptures are dated 1903 by Josef Limburg in his album. |

| 8 | Lowes, Will, and Christel Ludewig McCanless. Fabergé Eggs: A Retrospective Encyclopedia, 2001, p. 195. Other dates suggested for the opening of the Paris shop are 1922 from Tatiana Fabergé’s 2012 publication (details in endnote 9), and 1924 in Wikipedia. |

| 9 | Fabergé, Tatiana F., Kohler, Eric-Alain, and Valentin V. Skurlov. Fabergé: A Comprehensive Reference Book, 2012, pp. 16, 216. In 2023, one of the co-authors suggests “Leipzig in 1942”. |

| 10 | Information courtesy of Gundula Ancke, curator, Sculpture Collection, Stadtmuseum, Berlin. |

| 11 | Snowman, A. Kenneth. The Art of Carl Fabergé, 1953, p. 7. |

| 12 | See endnote 10. |

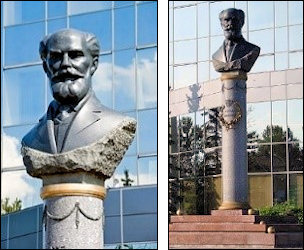

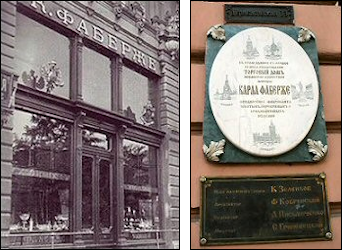

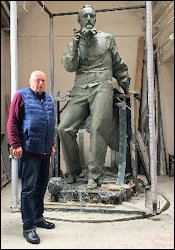

A chronology of memorials on view in public spaces shared by Fabergé Research Newsletter readers honor the jeweler Carl Fabergé (1846-1920), his father Gustav Fabergé (1814-1893), and Fabergé workmasters in St. Petersburg (Russia), Wiesbaden (Germany), Pully, La Roziaz (Vaud) in Switzerland, Odessa and Kiev (Ukraine), Pärnu (Estonia), Russian Republic of Karelia, Pojo (Pohja) and Ekenäs (Tammisaari, now Raseborg) in Finland.

Memorials: St. Petersburg (Russia) – Wiesbaden (Germany) – Pully, La Roziaz (Vaud) in Switzerland

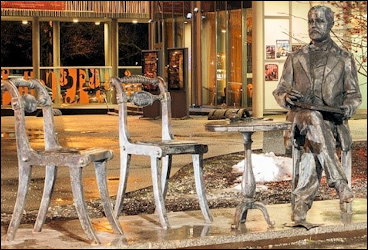

(B.) 1996 – St. Petersburg, Russia. Fabergé sculpture based on the original bust (A). Located on Fabergé Square (named in 1998) in front of “Russkiye Samotsvety/Russian Gems” jewelry business. (Fabergé, Tatiana F., Kohler, Eric-Alain, and Valentin V. Skurlov. Fabergé: A Comprehensive Reference Book, 2012, pp. 16, 216. Fabergé Research Newsletter, Spring 2020)

Memorials: Ukraine, Estonia, and the Russian Republic of Karelia

(E.) 2011 – Kiev, Ukraine. Plaque in honor of Carl Fabergé unveiled on Khreshchatyk Street at the location of the Fabergé shop in existence from 1905-1910, and merged with the Odessa branch of the firm. (Courtesy Paul Gilbert, Royal Russia; Fabergé Research Newsletter, Winter 2011-2012)

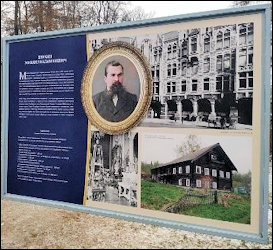

(F.) 2015 – Pärnu, Estonia. Memorial unveiled for the 200th anniversary of Gustav Fabergé’s birth (1814-1893), founder of the family’s jewelry firm in 1842, and father of Carl Fabergé (1846-1920). (Valentin Skurlov in Russian Jeweler, December 13, 2016).

Text on Monument Attachment (middle above): “Perkhin Mikhail Evlampievich. Born on May 22, 1860, in the village of Okulovskaya, Petrozavodsk district, Olonets province. He died on August 28, 1903, in St. Petersburg. Goldsmith since 1884. Head of the main workshop of the Fabergé firm.” Further details about the monument in a Russian television interview (25 minutes) with Valentin Skurlov. Two earlier publications contain additional Perkhin biographical data: Lowes, Will, and Christel Ludewig McCanless. Fabergé Eggs: A Retrospective Encyclopedia, 2001, p. 227; Tillander-Godenhielm, Ulla. Fabergé: His Masters and Artisans, 2018, pp. 71-85.

Memorials: Fabergé Workmasters Honored in Finland

(I.) Pihl family signboard unveiled in the 1990’s in Pojo (Pohja) church (west of Helsinki) with colored pictures of Oscar Knut Pihl and Alma Pihl, and a photograph of the Fabergé Imperial 1913 Winter Egg, Alma’s design. Oscar Knut (active 1887-1897), head of Fabergé’s Moscow jewelry workshop. Alma Pihl, Oscar’s daughter (active 1911-1917), designer at the St. Petersburg Fabergé jewelry workshop headed by her maternal uncle Albert Holmström, workmaster (active 1857-1903). Sponsors of the board (right): Mr. and Mrs. N.H. Simberg and Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm (middle) unveiling the memorial. (Archival data, Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm, Helsinki, Finland)

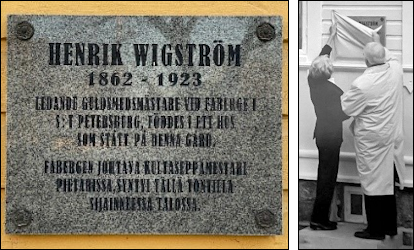

(J.) Memorial plague for Henrik Wigström, Fabergé firm head workmaster (active 1903-1917) at the Fabergé firm in St. Petersburg. Snapshot of his grand-daughter Anni Sarvi (left), and the great-grandson, Matti Virmakoski (right), unveiling the early 1990’s plaque on the spot where the Wigström birthplace once stood. The dedication text in the town of Ekenäs (Tammisaari) is in Swedish and Finnish. (Plaque photograph by Eva Tordera Nuño, Doctoral Researcher, Department of Art and Media (DAM), Aalto University School of Arts, Design, and Architecture; Unveiling snapshot by Ulla Tillander- Godenhielm)

Memorial Coins:

(L.) Prior to 2019, the late Annemiek Wintraecken compiled a detailed coin study with predominantly modern Fabergé egg interpretations. CIT Coin Invest AG in Liechtenstein has since 2020 issued in Mongolia commemorative coins using Fabergé egg photographs of four original eggs. The current museum location of the four original Fabergé eggs is given in the press kit without any further details. In the case of the Tsarevitch Egg (upper left 2023 issue) in the Pratt Collection since 1947, the coin’s existence was not known to the staff at the Virginia Museum of Art in Richmond, USA, before the coin went on sale.

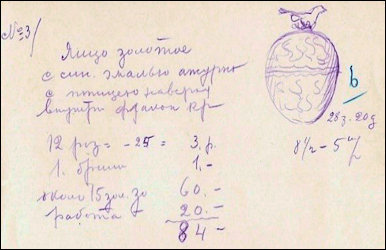

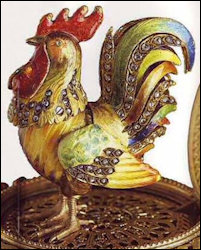

The Goznak List compiled by the Soviets in 1924 consists of 18 Easter Eggs, of which 17 Fabergé Tsar Imperial Eggs are recorded in the published literature. The new egg’s discovery was made at the end of 2020 in the Unified Fund of Samples and Documents preserved by the Goznak Joint Stock Company responsible for manufacturing banknotes and coins. The purpose of the list was to confirm the valuation made by the Gokhran (State Fund of Precious Metals and Precious Stones of the Russian Federation) before the sale of the eggs to the West in the 1920’s by the Moscow Jewelers’ Community (MJC). The detailed descriptions of the 18 eggs (on single sheets, 12 with sketches) are a fascinating addition to Fabergé egg research. The Bird Egg, a previously unknown Imperial Easter Egg belonging to Empress Maria Feodorovna, is in the collections of the Hillwood Estate, Museum and Gardens, Washington (DC). The Goznak list also provided important new information on the still missing Cherub(s) with Chariot Fabergé Imperial Egg offered to Maria Feodorovna by Alexander III. Additional highlights are presented in chronological order for the last two Romanov empresses, Maria Feodorovna (1847-1928) and Alexandra Feodorovna (1872-1918), who together received 50 Fabergé Easter eggs between 1885-1916.2

Bird Egg (date and master unknown, Maria Feodorovna, Sheet 6 of the Goznak List) is the previously unrecorded Imperial Easter Egg discovered on July 4, 2021, at the bottom of a vitrine in the Hillwood Museum by the authors Vincent Palmade and Dmitry Krivoshey. The bird (C.) matching the one on the sketch (A.) provided the first clue. The identification was later confirmed by the detailed written description in the sheet (A. translated text) – ‘blue enamel openwork’, ‘inside red bottle’, ‘12 roses’ (six rose-cut diamonds on each side of the bird), and ‘1 brill[iant]’ (one brilliant-cut diamond on top of the bird’s head). The restoration conducted by Nikolai Bachmakov, antique restorer, revealed the Bird Egg is made out of 22 carat gold, which is an unusually high value. There would not have been a discovery, if an intrigued Wilfried Zeisler, Hillwood’s Deputy Director and Chief Curator, had not in 2019 moved the Bird Egg from storage to a display case for museum visitors to enjoy.

(Courtesy Goznak Joint Stock Company, Moscow)

(Courtesy Hillwood Estate,

Museum & Gardens, Washington, DC)

(Goznak List, Sheet 6, 1924)

(Courtesy Hillwood Estate,

Museum & Gardens, Washington, DC)

(Habsburg, Gèza von,

Fabergé Revealed, 2011, p. 269)

(Mieks Fabergé Eggs)

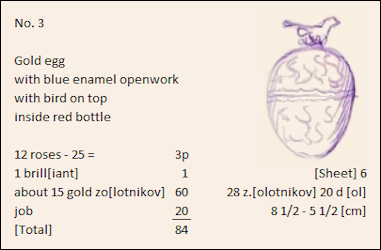

At the present time, we do not risk attributing the Bird Egg to Fabergé even though it is exclusively surrounded by Fabergé Tsar Imperial Eggs in the 1924 Goznak List, and the 1917 Anichkov Palace Inventory of pieces belonging to Empress Maria Feodorovna.3 In addition, the bird on top of the egg (C.) is in the style and craftmanship of other birds on Fabergé eggs, i.e., the 1898 Pelican (D.) and the 1904 Kelch Chanticleer (E.) Eggs. Such bird décor on top of eggs seems to have been used only by Fabergé.

The lack of an available slot for the Bird Egg in the known Tsar Imperial Egg Chronology for Empress Maria Feodorovna leaves three possibilities:

- Was the Bird Egg offered by a person very dear to Empress Maria Feodorovna (wife of Alexander III) other than the Tsar, since it was among her Tsar Imperial Eggs (all by Fabergé) in the Anichkov Palace?

- Was the Bird Egg an earlier (Tsar) Imperial Egg? For example, it could have been presented by Alexander II (reigned 1855 to his assassination in 1881) to his wife Empress Maria Alexandrovna (1824-1880), and subsequently inherited by Maria Feodorovna through her husband Alexander III?

- Was the Bird Egg specially commissioned by Maria Feodorovna as she was known for her love of birds? This possibility was suggested by Wilfried Zeisler.

Known provenance of the Bird Egg in reverse:

- 1973-Current Hillwood Estate, Museum and Gardens in Washington (DC).

- 1946-1973 Marjorie Merriweather Post received the egg as a gift from her husband Joseph Edward Davies, former US Ambassador to the USSR, who bought it from Berry-Hill Antiques in May-June 1946.4

- 1927-1946 Berry-Hill Antiques. The presence of the Bird Egg on the 1924 Goznak List and its absence from the 1927 list of unsold eggs by the MJC5 imply it was sold to the West between 1924 and 1927. The Bird Egg was probably sold to Frederick Berry, Ltd., London (before it became Berry-Hill Antiques, New York, at the beginning of World War II6). This transaction perhaps also included the First Hen Egg and the Resurrection Egg, also sold by the MJC to the West between 1924 and 1927, and Frederick Berry, Ltd. sold at auction in 1934.7

- 1917-1927 Russian/Soviet Government. The egg is mentioned on the 1924 Goznak List. Since the purpose of the Goznak List was to confirm Gokhran’s valuation, the Bird Egg had to be among the pieces transferred to Gokhran in 1922 by the governmental commission accounting art objects from the Imperial palaces. There is indeed one (and fortunately only one) egg among these pieces with a description matching the Bird Egg.8

- Unknown-1917 Empress Maria Feodorovna. The 1922 entry mentioned above for the Bird Egg refers to its listing in the 1917 Anichkov Palace Inventory of pieces belonging to Maria Feodorovna, thus establishing its Imperial provenance. The dates of manufacture and delivery as well as the manufacturer of the Bird Egg are not yet known and as suggested, it could have been an earlier (Tsar) Imperial Egg inherited by Maria Feodorovna.

The authors are continuing their research on the Bird Egg and would be grateful for any clues.

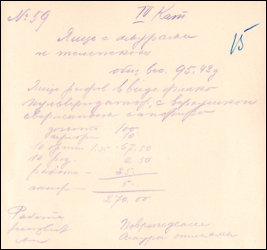

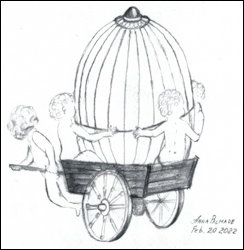

Cherub(s) with Chariot Egg (1888, Maria Feodorovna, Sheet 15) is the only egg in the Goznak List which has yet to be found. Unfortunately, the Goznak Sheet (F.) describing the egg has no sketch leaving researchers only with the reflection in Maria Feodorovna’s vitrine at the 1902 von Dervis Exhibition (G.), an image discovered by Anna and Vincent Palmade in 2007.9

written description without sketch

(Goznak List, Sheet 15, 1924)

with Chariot Egg

(Unknown author, Public domain,

via Wikipedia Commons;

Fabergé Research Newsletter,

Fall and Winter 2022)

with Chariot Egg, February 20, 2022

(Courtesy Anna Palmade)

Fortunately, the text in the Goznak Sheet provides new information which may assist in discovering it:

- ‘Several cupids are broken off‘ confirmed by Greg Daubney and Chad Solon’s hypothesis10 of more than one cherub being part of the egg. Anna Palmade updated her earlier drawing (H.) of the egg.

- ‘Reeded egg in the shape of a spray bottle‘ confirms the reeds glimpsed on the reflection and the description of the egg – ‘gold egg-shaped flask … on stand in the form of a chariot‘11 in the 1922 inventory of pieces transferred to the Gokhran.

- ‘Work of an unknown craftsman‘ implies the egg was made by Erik Kollin. In effect, the egg had to have been made by either Fabergé workmasters: Holmström [active 1857-1903], or senior workmaster Kollin [active 1870-1901], or head workmaster Perkhin [active 1886-1903] with 1888 being the likely transition of workshop leadership from Kollin to Perkhin. Since the authors of the Goznak List recognized the marks of Holmström (confused with the one of Hollming on Sheet 5, Third Imperial Egg) and Perkhin (Sheets 9, 16, 17, and 19), this leaves Kollin as the only possibility for the ‘unknown craftsman’.

- And finally like the Bird Egg, its presence on the 1924 Goznak List, and its absence from the 1927 list of unsold eggs by the MJC imply the Cherub(s) with Chariot Egg was sold to the West between 1924 and 1927. It is thus likely still to be extant, albeit it may be separated from its chariot and/or cherub(s).

Other Fabergé Imperial Eggs presented to Maria Feodorovna (1847-1928)12:

First Hen Egg (1885, Maria Feodorovna, Sheet 7). Agathon Fabergé (1876-1951, second son of Karl Fabergé) helped the Soviets evaluate the Imperial Treasures and is mentioned as having indicated (correctly) the chicken inside the egg used to contain a crown. This observation suggests he informed the Soviets the unmarked First Hen Egg is a Fabergé Imperial Egg.

Third Imperial Egg (1887, Maria Feodorovna, Sheet 5) was greeted with much enthusiasm when the egg surfaced and was authenticated in 2014 by Kieran McCarthy of the British jewelry dealer Wartski.13 The Goznak Sheet states the egg was made by August Hollming [active 1880-1913], while the discovered egg bears the mark ![]() for August Holmström. The mark

for August Holmström. The mark ![]() for August Hollming is almost identical – a common mistake, ironically confirming the authenticity of the 1887 egg.

for August Hollming is almost identical – a common mistake, ironically confirming the authenticity of the 1887 egg.

Danish Palaces Egg (1890, Maria Feodorovna, Sheet 9) is dated 1889 by mistake, probably because the miniatures are signed and dated 1889.

Diamond Trellis Egg (1892, Maria Feodorovna, Sheet 11). The mechanical elephant surprise was already separated from the egg in 1924. It was identified during a 2015 restoration project in the Royal Collection by Caroline de Guitaut, Senior Curator of Decorative Arts.14

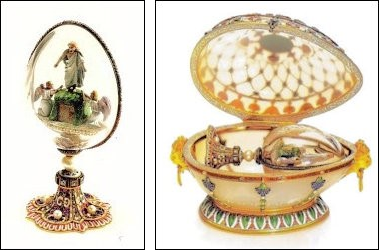

1894 Imperial Renaissance Egg with the Resurrection Egg

(Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia); von Habsburg,

Géza, Fabergé; Treasures from Imperial Russia, Link of

Times Foundation, 2004, p. 121; Fabergé Research

Newsletter, Fall and Winter 2017.

of the 1902 Clover Leaf and 1907 Rose Trellis Eggs

(Mieks Fabergé Eggs, details endnote 12)

Renaissance Egg (1894, Maria Feodorovna, Sheet 19). There is no mention of its surprise, which is probably the Resurrection Egg (1894, Maria Feodorovna, Sheet 21). The Forbes Magazine Collection in New York City begun by Malcolm Forbes (1919-1990) owned both eggs. His son, Christopher “Kip” Forbes, made a strong case for the Resurrection Egg to be the surprise of the Renaissance Egg, since the Resurrection Egg (I.) fits within the Renaissance Egg (I.) perfectly.15 Its proximity to the Renaissance Egg on the Goznak List further strengthens his case. (Sheet 20, which separates the surprise from its egg, is a duplicate of Sheet 5 without the sketch.)

Cockerel Egg (1900, Maria Feodorovna, Sheet 17). Fabergé workmaster Fyodor Afanasiev [active 1903-1913], estimated the Egg to be worth 10,000 Rubles. It indicates Fyodor Afanasiev, like Agathon Fabergé, was also an adviser for the Soviets.

Swan Egg (1906, Maria Feodorovna, Sheet 12). The description mentions a slight damage to the neck of the mechanical swan.

Napoleonic Egg (1912, Maria Feodorovna, Sheet 23) is shown together with its surprise, a folding screen displaying the six regiments for which Maria Feodorovna was an honorary colonel.

Catherine the Great Egg (1914, Maria Feodorovna, Sheet 14) is shown with its original stand, now replaced by a modern stand. The surprise, two figures carrying Empress Catherine II in a sedan chair, was already separated from the egg in 1924.

Fabergé Imperial Eggs presented to Alexandra Feodorovna (1872-1918)16:

Flower Basket Egg (1901, Alexandra Feodorovna, Sheet 10) was not on the list of Imperial Fabergé Eggs until 1989 when George W. Terrell, Jr., (Professor of History and Geography at Gadsden Community College, Alabama) recognized it in the 1902 von Dervis picture of the vitrine containing the Imperial Eggs belonging to Alexandra Feodorovna.17 It had not been recognized because marks where lost when the base was replaced. The Goznak Sheet, which mentions the base is damaged, explains why the original (white) enameled base was replaced with the current (blue) enameled base, and suggests the replacement took place after 1924.18

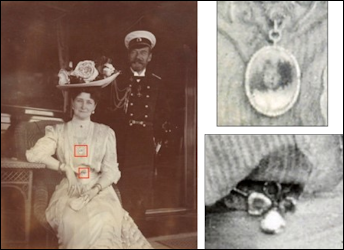

Clover Leaf Egg (1902, Alexandra Feodorovna, Sheet 13) and the Rose Trellis Egg (1907, Alexandra Feodorovna, Sheet 8) are forever linked with the 2017 discovery made by Fabergé egg historian Annemiek Wintraecken and Fabergé enthusiast Greg Daubney. Empress Alexandra Feodorovna is seen in a 1908 photograph (J.) wearing the surprises (a four-leaf clover brooch and a medallion-pendant) from the two eggs. Their absence from the Goznak List shows they were already missing in 1924.

Colonnade Egg (1910, Alexandra Feodorovna, Sheet 18) is erroneously attributed to Mikhail Perkhin instead of Henrik Wigström, probably because Wigström’s mark

Red Cross Triptych Egg (1915, Alexandra Feodorovna, Sheet 22) is shown open and closed to display the Triptych surprise.

Our highlights of the Goznak List revealed the Bird Egg as a new Imperial Egg which belonged to Empress Maria Feodorovna, provided new important information on the missing Cherub(s) with Chariot Egg, and confirmed the authenticity of the Third Imperial Egg. No doubt, Russian archives still conceal many more secrets.

| 1 | The State Museum Hermitage, Jewellery and Material Culture: Collected Articles (ЮВЕЛИРНОЕ ИСКУССТВО И МАТЕРИАЛЬНАЯ КУЛЬТУРА), Issue 7, 2023. The 1924 Goznak List article in Russian is on pp. 448-467 in the above link. Faberge-related English summaries (Part III) start on p. 525, and an English index with links to the Russian article begins on p. 536. Our thanks to the Director’s Office of the State Hermitage Museum for permission to include the Fabergé research studies. |

| 2 | Fabergé Egg Chronology published by the late Annemiek Wintraecken on her scholarly website is entitled Mieks Fabergé Eggs. |

| 3 | Department of Manuscripts, Printed and Graphic Funds (ORPGF), Kremlin Armoury Museum, F.20.1917.D5.C.203. |

| 4 | Library of Congress Archives contain Joseph Edward Davies Papers, 1860–1958; Part II: Family and Personal File, 1902–1958; BOX II: Household Papers #7. |

| 5 | Fabergé, Tatiana, Proler, Lynette, and Valentin Skurlov. The Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs, 1997, p. 257. |

| 6 | McCanless, Christel Ludewig. Fabergé and His Works, 1994, p. 52, entry 135 (last known advertisement of Frederick Berry, Ltd. in London on August 1939, and p. 54, entry 148, first known advertisement of Berry-Hill Antiques in New York on February 1941). |

| 7 | Lowes, Will, and Christel Ludewig McCanless. Fabergé Eggs, A Retrospective Encyclopedia, 2001, pp. 19, 147. |

| 8 | Department of Manuscripts, Printed and Graphic Funds (ORPGF), Kremlin Armoury Museum, F.20.1917.D5.L.203. |

| 9 | Palmade, Anna and Vincent, “Two Lost Fabergé Imperial Eggs Discovered in an Archival Photograph”, Fabergé Research Site, November 2007. |

| 10 | Fabergé Research Newsletter, Fall and Winter 2022. |

| 11 | Fabergé, Tatiana, Proler, Lynette, and Valentin Skurlov. The Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs, 1997, p. 100. |

| 12 | Chronological lists for Fabergé eggs: Mieks Fabergé Eggs by Annemiek Wintraecken cited with egg links; Fabergé Imperial Egg Chronology by Christel Ludewig McCanless. |

| 13 | McCarthy, Kieran. “The Third Imperial Easter Egg“. (Courtesy Wartski) |

| 14 | Diamond Trellis Egg; Video featuring the mechanical Fabergé elephant found in 2015. |

| 15 | Renaissance Egg and the Resurrection Egg are listed as Eggs of “Imperial Quality” on the Mieks Fabergé Eggs website. |

| 16 | For details see endnote 12. |

| 17 | Lowes, Will and Christel Ludewig McCanless. Fabergé Eggs: A Retrospective Encyclopedia, 2001, p. 77. |

| 18 | 1901 Flower Basket Egg |

Fabergé collections displayed in 14 permanent plus occasional temporary venues are enumerated in the Exhibitions section of the Fabergé Research Site. Additional updates are summarized below. Additional collections or corrections, please share specifics. Contact: Christel McCanless

Houston, Texas. Houston Museum of Natural Science

New location! The Artie and Dorothy McFerrin Collection re-opened in Brown Hall for one year beginning in August 2023. An update with an accompanying booklet was featured in the Fabergé Research Newsletter, Summer 2022. Three Fabergé eggs (1892 Diamond Trellis, Nobel Ice, and Kelch Rocaille) plus three tiaras are shown in the current venue highlighted on a new website.

A docent training manual, The McFerrin Collection: Fabergé Gallery Notes, compiled by Pat Hazlett, Master Docent Fabergé Hall Lead, is a unique learning tool to gain insight into the genre of Fabergé and the amazing objects in the McFerrin Collection of Fabergé and Russian decorative art objects. The availability of such a teaching tool appears to be a first occurrence among the more than a dozen permanent exhibitions worldwide.

London, United Kingdom. Royal Collection of Queen Elizabeth II – Is one of the largest Fabergé collections with three Imperial Easter eggs: 1901 Basket of Flowers Egg, 1910 Colonnade Egg, 1914 Mosaic Egg, and one Kelch Egg (Twelve Panel Egg, 1899), all objects are described online. Temporary exhibitions feature small parts of the collection. Monograph by Caroline de Guitaut, Fabergé in the Royal Collection (2003) is available as a PDF. Research for a comprehensive catalog is underway. New! Discover the Stories that Link Objects in the Royal Collection: Twelve topics with new links include Fabergé workmasters Erik August Kollin (1836-1901) with 18 objects, Mikhail Perkhin (1860-1903) with 101 objects, and Henrik Immanuel Wigström (1862-1923) with 85 objects.

Moscow, Russia. Kremlin Armoury Museum – The museum treasures include 10 Imperial Easter Eggs which rarely travel: 1891 Memory of Azov Egg, 1899 Bouquet of Lilies Clock Egg, 1900 Trans-Siberian Railway Egg, 1902 Clover Leaf Egg, 1906 Moscow Kremlin Egg, 1908 Alexander Palace Egg, 1909 Standart Yacht Egg, 1910 Alexander III Equestrian Egg, 1913 Romanov Tercentenary Egg, and 1916 Steel Military Egg. Beautifully illustrated books with informative text by Tatiana Muntian of the museum’s staff describe the collection well. News! Kremlin Fabergé Collection to Get New Home in 2024 (Courtesy © Paul Gilbert website, July 28, 2023)

Polesden Lacey (Edwardian house and estate, near Dorking in Surrey, England, owned and run by the National Trust since 1942) March 1 – October 29, 2023 Treasured Possessions: Riches of Polesden Lacey exhibition features the Greville Collection and a separate gallery with Objets de Fantaisie: Fabergé and Cartier. Mrs. Margaret Greville made purchases from the London Fabergé branch of no fewer than 31 items, including a carving of Caesar, King Edward VII’s wire fox terrier, which she gave to Queen Alexandra after the King’s death, and is in the Royal Collection. Lecture! September 20, 2023 “The Life and Work of Peter Carl Fabergé” by John Benjamin, industry-leading Fabergé and jewelry expert as seen on the British Antiques Roadshow. He was appointed to the role of Jewelry Advisor to the National Trust in 2021, and is currently cataloging the National Trust collection of Fabergé, which includes the Fabergé/Cartier display at Polesden Lacey. The Cultural Heritage Magazine (CHM Spring 2013 issue) with a scholarly article, “Treasured Collections, Treasured Possessions: The Formation of Margaret Greville’s Collection” by Richard Ashbourne, James Rothwell, and Alice Strickland, pp. 24-33. (Our special thanks to Ms. Strickland for sharing exhibition and publication details.)

Auctions

Sotheby’s London, July 11, 2023. Fabergé, Imperial & Revolutionary Works of Art with 52 Fabergé lots. Preview July 3, 2023, and review September 13, 2023, by Andre Ruzhnikov.

New! Sotheby’s Sealed platform is engineered to provide bidders and buyers absolute privacy, while ensuring the final sale price remains confidential.

Bonhams Network News

- Bonhams Skinner, Marlborough, Massachusetts, European Décor and Design, Part II, July 8-9, 2023. Lot 791 is discussed in Fabergé Cigarette Case Lights Up Bonhams Skinner European Auction, Antiques and the Arts Weekly, July 24, 2023 – “The top result of either session was a silver and enamel cigarette case from Fabergé that closed at $76,700. Made in Moscow between 1908 and 1917, … Feodor Rückert painted a detailed scene of Ivan Tsarevich Riding the Grey Wolf …”

- Rasmussen, a part of the Bonhams network, is publishing very attractive hard copy auction catalogs. They offer a unique service for their digitized copies, i.e., downloads split into 4 smaller sections. However, they no longer show past auction lots older than two weeks on their website.

New Books on the Horizon with Details Shared by the Authors:

and Objects from the Second Henrik Wigström Album, Unicorn Press,

available October 2023 at Amazon.

Geoffrey Munn, managing director of London jewelers Wartski, where he had worked since the age of 19, recently completed his autobiography, A Touch of Gold: The Reminiscences of Geoffrey Munn, in a new phase in his life – retirement! I asked him to share a few lines about his latest accomplishment after having published four books on jewelry, many exhibition catalogs, and the history of the Wartski firm for the first 150 years. His trademark of an engaging smile and the twinkle of his eyes always signaled a surprise at the end of yet another exciting, but true tale coupled with a teachable moment. Geoffrey Munn writes, “Fabergé enthusiasts will not be disappointed by this book where the author’s earliest encounters with the collectors and collections are set down. Frank Sinatra, Bing Crosby, and Joan Rivers are remembered with affection whilst the dramatic rediscovery of the 1895 Fabergé Blue Serpent Egg Clock with Prince Rainier is there too. Glittering diamonds add grist to the mill and amusing stories of tiaras light up the text. Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother and Princess Margaret are center stage and there is even a story of a brooch made for the new Queen, presented like Fabergé would have done, as a surprise in a chocolate Easter egg.”

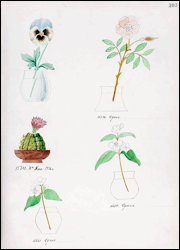

Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm’s second research study, Fabergé: The Twilight Years, is a companion volume to The Golden Years of Fabergé (2000), both of which reveal production drawings from Fabergé’s main workshop led by Henrik Wigström, head workmaster active from 1903-1917. The first album shows objects produced mainly between 1911 and 1912, whereas most of the drawings in the second album Tillander discovered in a library are from the years of World War I leading up to the demise of the Empire. The plates are shown in their numerical order scaled down to 71% of their original size, and if the object is extant, it is shown next to the drawing also reduced in scale. The drawings are paired with articles and essays either relating to the drawings or to the various techniques and materials used by Fabergé in his production. Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm chose to respond to my request for details about her book by crediting each of her contributors:

- A comprehensive article on engine turning (guilloché) written by David Wood-Heath, specialist on this signature technique of Fabergé, is paired with an essay on enameling by the master enameller, Henrik Kihlman.

- Ludmila Budrina, mineralogist and Professor of Modern Art History at the Ural Federal University, shares interesting information about hardstones used by Fabergé in his oeuvre.

- Cigarette cases were best sellers at Fabergé during the decades leading up to the Russian Revolution i.e., the Twilight Years. Directly related to the drawings are articles on cigarette smoking and cigarette cases by Timothy Adams, a topic he has explored in permanent Fabergé collections in museums. He also discusses two commissions from the Royal Court of Siam.

- Galina Korneva and Tatiana Cheboksarova, the latter sadly no longer among us, have studied in detail Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna’s Collection of Fabergé Flowers and Their Fate and the story of a yellow rose during many decades of research. Alexander von Solodkoff added a delightful story on the Grand Duchess’s visit to Paris.

- Alexander von Solodkoff has added a comprehensive article on 15 drawings of table and desk clocks shown in the album. Many of the clocks in the drawings have survived, and it is a delight to see a Fabergé clock in a photograph next to its production drawing.

- Cynthia Coleman Sparke in her interesting article elaborates on an enigmatic egg, the size of an Imperial Easter Egg.

- Alexis de Tiesenhausen and Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm contributed essays on Imperial Presentation boxes matching production drawings.

- Géza von Habsburg describes an unusual enameling technique – émail pékin (thousand-stripe Peking enamel) which Fabergé successfully ‘copied’ from Cartier.

- Emmanuel Ducamp, involved in the publication of Golden Years, gives readers “Messages from the Heart” by telling once more the romantic story of Princess Cécile Murat and Charles Luzarche d’Azay. The article is illustrated with two cigarette cases made in 1914.

Readers aware of extant Fabergé articles matching Wigström production drawings not in The Golden Years (2000) or Twilight Years (2023) publications, please share results. Contact: Christel McCanless

Russian Art History Series: The State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg (Russia) has since 1996 published a book series entitled ЮВЕЛИРНОЕ ИСКУСС ТВО И МАТЕРИАЛЬНАЯ КУЛЬТУРА (Jewellery Art and Material Culture: Collected Articles). St. Petersburg: State Hermitage. Began in 1996 –

Collections of abstracts: I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII | VIII | IX-X | XI | XII | XIII | XIV | XV | XVI | XVII | XVIII | XIX

Collections of articles: 2001 | 2006 | 2015 | 2017 | 2019 | 2021 | 2023

The 2023 printed edition, volume 7 of Jewellery Art and Material Culture: Collected Articles (ISBN 978-5-907653-08-5) has 498 pages, and its digital edition 540 pages. Fabergé-related English summaries (Part III) start on p. 525, and an English index with links to the Russian articles begins on p. 536. The Director’s Office of the State Hermitage Museum has kindly granted permission to share the electronic version for Part III, and the seven Fabergé-related research studies:

PART III

- Albert Becker, Mikhail Dubrovin. Moscow name stamps with the initials ‘К Ф’ [K F] in an oval shield. Fend or Fabergé?

Developed by the State Research Institute for Restoration, the database Russian Hallmarks on Applied Art Objects in Precious Metals (Late Seventeenth – Early Twentieth Centuries) features over 5,800 metal articles and about 100,000 microscopic hallmarks thereon. The study compares and analyzes the photographs available from the database and depicting late nineteenth – early twentieth-century Moscow name stamps with the initials ‘К’ [K] and ‘Ф’ [F] in an oval shield (with or without dots between the letters). The study attempts to establish whether the stamps belonged to Karl Fend’s workshop (factory) or to the Moscow branch of Carl Fabergé, and outlines the attribution criteria. The findings will make it possible to confidently identify the authorship of any objects with this name stamp. (English summary, p. 525)

- Nadezhda Ivanova. Henrik Wigström’s stamps on the objects from the Tsaritsyno State Museum-Reserve. Attribution aspects.

The study aims to clarify the attribution of two museum objects with Henrik Wigström’s stamps held by the Tsaritsyno State Museum-Reserve, namely a Carl Fabergé lorgnette in a case (КП-8111/1, 2) and the carved table sculpture, A Frog Climbing a Column (КП-7832). Both items were acquired by the museum in 1990–1991 as works created by Henrik Wigström of the House of Fabergé in the early twentieth century. The objects differ by the artistic level and workmanship. The authorship attribution relied on several types of analysis and involved a study of the high-quality published analytical sources about the objects known to have been created by Wigström, and a comparison of the name stamps borne by the two Tsaritsyno exhibits with reference samples. The stylistic comparison of the exhibits was conducted on several variables, including the material, technique and size; composition and proportions, shape, style, artistic merits and creative solutions typical for Wigström. The style, design, décor and structural features of the cased lorgnette and the stamp on it are consistent with works by Wigström, which testifies to the authenticity of the object. The chapter provides the following museum description and attribution of the item: lorgnette (КП-8111/1, Мт-1749, СВ-628) – St. Petersburg, Russia, 1908–1917, House of Fabergé, craftsman Henrik Wigström; gold, silver, sapphires; guilloche enamel, painted enamel, casting, embossing, engraving; 161 × 34 mm; lorgnette case (КП-8111/2, Д-1593) – Russia, early twentieth century, House of Fabergé, wood, velvet, satin, metal, 187 × 56 × 26 mm. The analysis of the table sculpture has shown that the artifact differs from the reference samples in some important parameters, including art form, workmanship and materials; the stamps also diverge from the reference samples in terms of execution. This leads us to conclude that the sculpture is a late twentieth-century imitation of a Fabergé sculpture by Wigström. (English summary, p. 526)

- Dmitry Krivoshey, Elena Yarovaya. Public, territorial and private coats of arms in Fabergé’s works.

The chapter provides authorship attributions for works by Carl Fabergé relying on methodologies used by auxiliary historical disciplines including heraldry. Many products by the firm of Fabergé bear coats of arms, including state, territorial (primarily municipal) and private arms, Russian or foreign. The Russian state eagle was displayed on royal gifts from His Majesty’s Cabinet; city arms adorned presentation wine cups and ‘bread-and-salt’ dishes offered to the Russian royals as gifts by different class groups; noblemen’s desktop stamps and tableware were emblazoned with personal coats of arms. Identifying private coats of arms makes it possible to link each specific artwork to its owner (family or individual). The article provides examples of items with brooches and rings for women; city and governorate arms on trays, salt cellars and commemorative medals; personal coats of arms on kovsh wine dippers, bratina wine bowls, domestic utensils, photograph frames, and stamps. Individual owners have been identified for some of the items. The chapter establishes the iconographical sources for the heraldic images shown on Fabergé goods. (English summary, p. 527)

- Dmitry Krivoshey. Badges produced by the firms of Carl Fabergé, Friedrich Koehli and Carl Bolin for the participants of the Hermitage performances. [Ed. Note: Koechli is the correct spelling, St. Petersburg retail jeweler (active 1870-1909)]

The chapter is the first analysis of the works created at the turn of the twentieth century by the leading Russian jewellers for participants in the Hermitage Theatre productions. The Russian State Historical Archive has retained a set of documents recording presents given to those who performed in the Imperial Hermitage Theatre. The archival files of the 1899–1900, 1902–1903 and 1903–1904 theatre seasons contain designs for over 140 objects and bills for 950 objects ordered from Carl Fabergé, Friedrich Koehli, Karl Gan (Hahn) and Carl Bolin. The valuable gifts included brooches, bracelets, tie pins, cuff links and commemorative medals with the stylised letter ‘Э’ (emblem of the Hermitage Theatre). Of particular interest are the lists of award-winning artists, including directors Pyotr Gnedich and Alexey Kondratyev, ballet masters Nikolay Aistov and Marius Petipa, prima ballerinas Mathilde Kschessinska, Olga Preobrazhenskaya and Anna Pavlova, and singers Feodor Chaliapin, Nikolay Figner and Ivan Yershov. The appendix to the chapter contains lists of actors of music and drama theatres rewarded for their performances at the Hermitage Theatre in keeping with their ranks, and specifies the amounts spent on the gifts. (English summary, p. 528)

- Andrey Bogdanov, Dmitry Krivoshey, Anna Palmade, Vincent Palmade, Valentin Skurlov. New data on the history of Imperial Easter eggs by the firm of Fabergé in the 1920s. Based on the materials of Goznak JSC.

The study focuses on recently discovered documents concerning the transfer of Fabergé Imperial Easter eggs from the Gokhran (State Institution on Formation of the State Fund of Precious Metals and Precious Stones of the Russian Federation) to the Moscow Jewellery Partnership (MIUT) and Antikvariat All-Union Association for subsequent sale to western buyers. Held in the Unified Collection of Models and Documents at Goznak JSC, the documents expand our knowledge on Imperial Easter eggs made by Fabergé. The two pieces of data which are of particular value are drawings of the eggs made by members of the expert panel (the names of the panellists are specified in the chapter) and information on the asking prices for the Easter eggs. The new findings will provide more clarity on the provenance of the unique creations of the firm of Fabergé and pose new questions about the fate of these masterpieces of world jewellery art. (English summary, p. 529; Highlights from the Recently Discovered 1924 Goznak List of Fabergé Imperial Eggs)

- Mikhail Yudin. The firm of Fabergé as the subject of myths.

The study presents an analysis of references to the firm of Fabergé in Russian and international publications. The article suggests that the unanimous admiration for Fabergé’s work expressed by the researchers is not always justified. Relying on a variety of published sources (including contemporaries’ testimonials and archival documents), the study highlights a number of disputable issues surrounding ‘the Fabergé phenomenon’. In particular, the chapter addresses several Fabergé works admired by the vast majority of modern researchers and analyzes the items from the viewpoints of style and taste. The study also examines the involvement of the firm of Fabergé in art and industrial exhibitions, both national (Moscow in 1882, Nizhny Novgorod in 1896) and international (Copenhagen in 1888, Stockholm in 1897, Paris in 1900). The chapter also focuses on the company’s awards, its rise to world fame and the evolution of Fabergé works from the ‘market goods’ they used to be after 1917 to the objects of popular admiration they are at present. (English summary, p. 530)

- Viktoria Petrova. Modern carved gemstones. Inheriting the Fabergé traditions.

Gemstone carving in Russia has been regarded as a national craft since the eighteenth century. The art reached its heyday in the second half of the nineteenth century with the establishment of the Ural and the St. Petersburg gemstone carving styles. Both the Ural and the St. Petersburg schools of gemstone carving have retained their leading positions in modern jewellery; the international jewellery community recognises Russia’s leadership in gemstone carving art. Although far from being Carl Fabergé’s core line of business, gradually emerged as an important part of the company’s work in the late nineteenth to early twentieth century. Artistic carved gemstones, particularly ‘the Russian types’, enjoyed the same level of popularity as Fabergé Easter eggs. Together with Alexey Denisov-Uralsky, Avenir Sumin and a number of other craftspeople, Carl Fabergé laid down the traditions of modern gemstone carving. By blending the expertise of the Ural gemstone carvers, with the European traditions and Asian cultural influences, Carl Fabergé shaped the unique identity of gemstone sculpture. Gemstone carving remains one of the most appealing creative vistas for today’s jewellers. Market data show that gemstone statuary enjoys high commercial popularity. Like a century ago, monolithic sculptures and polychrome 3D mosaics are acquired for private collections and museums, used as status symbols and valuable presents. The Fabergé traditions continue to play a significant role in promoting this type of product. Traditional forms, including depictions of Russian cultural and historical personalities, animal images and floral compositions, remain particularly attractive to customers. Modern masters combine traditional interpretations of forms and textures with original perspectives on subjects and techniques. (English summary, p. 531)

Are there Fabergé research articles/summaries in previous editions of Jewellery and Material Culture: Collected Articles? Share details for the benefits of the next generation of researchers, contact: Christel McCanless

- 2017 Natalia Aleksandrovna Korsakova, Fabergé Works in the Collection of the Cossack Troops of the Kuban … (Courtesy John Emerich, Bronze Horseman)

- 2021 (digital) Dmitry Yuryevich Krivoshey and Elena Aleksandrovna Yarovaya Elena Aleksandrovna, Monograms in Products of the Firm Fabergé. Experience Description, Systematization and Attribution.

Dealer archives which include sold and still available Fabergé objects with detailed descriptions plus photographs (front and back) as well as developing a trained eye from handling or examining auction lots during previewing events are excellent ways to avoid an unfortunate purchase.

- A La Vieille Russie, New York (NY) Selections from our Fabergé Collection

- John Atzbach Antiques, Redmond (WA) Fabergé

- Romanov Russia, Chicago (IL) Fabergé

- Ruznikov Fine Art & Antiques, London (UK) Fabergé

- Wartski, London (UK) Fabergé and Archive

Powerpoint program, Čudoviti Fabergé: veličastna velikonočna jajca (Magnificent Fabergé: Magnificent Easter Eggs) by newsletter contributor Riana Benko delighted her audience gathered in the local library of Nova Gorica, Slovenia, near the Italian border.

Research paper presented by Dmitry Krivoshei, Fabergé Advertising Tokens (Рекламные жетоны фирмы «Фаберже») at the XXII Russian Numismatics Conference. Smolensk, 2023. In Russian.

Three Tools to Make Your Publication Adventure a Success:

Fact-checking – Inverted Pyramid – Copyright and Permission Requirements

Fact-checking has gone awry and in our modern electronic world when writing a document or an email “one has 15 seconds – the time it takes to read 35 words – to grab a reader’s attention. After that 45% of readers will stop paying close attention … even though human attention span has remained the same since the 1800’s, because today there are more things competing for our attention.”1

Inverted pyramid writing style refers to a story structure where the most important information (or what might even be considered the conclusion) is presented first. The five W’s and one H (who, what, where, when, why, and how) appear at the start of a story, followed by supporting details and background information. The Fabergé Research Newsletter does not use the alternate academic style of writing in which an abstract may summarize the main findings, and the content focuses first on the details, then leads to the conclusion at the end of the article. This style sometimes resembles a travelogue from A-Z.

(AFDPO) / derivative work: Makeemlighter, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Copyright and Permission Requirements

Copyright and Permission Laws change frequently so doing your own research on this topic ahead of time is required. In your articles and picture selections you must keep in mind your work, and any content from other published sources must meet the required International Laws on this subject. Why? Because your work could be hosted on a webserver outside your country, provided as a service outside your country, or any number of other reasons. Some people try to justify getting around some or all these laws by saying they do not apply to my country. This is only true, if it pertains to you and you alone. Once you start advising others or want others to use your content their country’s laws and agreements with other countries go into effect. Any work you edit or publish must have proper copyright and permission documentation that apply on how you intend to use the material – this must meet all International Laws period (no way around it!). More…