Victoria & Albert Museum, November 20, 2021 – May 8, 2022

Book: McCarthy, Kieran, and Hanne Faurby

Fabergé: Romance to Revolution, [2021]

Preservation/Conservation Efforts

(A.) Exhibit Entrance Showcasing Fabergé’s Miniature

Imperial Regalia

(Courtesy of the Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia)

(B.) Fabergé Enamel Color Palette with Guilloché Designs from the

Mirabaud Collection

(McCarthy, Kieran and Hanne Faurby,

Fabergé: Romance to Revolution, [2021], p. 67)

(C.) Adams, Timothy and Christel Ludewig

McCanless, “Fabergé Cossack Figures

Created from Russian Gemstones”,

Gems & Gemology, Summer 2016, Vol. 52, No. 2

(Photographs Courtesy of Pavlovsk State

Museum and Wartski, London; McCarthy and

Faurby, pp. 72-75)

Katrina Warne, a Fabergé enthusiast visiting the 1977 Fabergé venue as a young person, vividly remembers the long queues around the block at the V&A Museum. About the 2021/22 venue she writes:

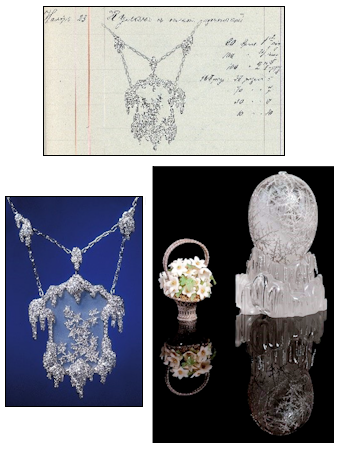

Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm, a practicing jeweler for decades in the A. Tillander jewelry firm, patiently explained in a phone call how Fabergé’s workmasters designed small prototypes in which their skills, techniques, and applications to make larger pieces in 3-D formats and transferring the designs from a flat surface to a curved one were developed. Examples she sent for further study are illustrated for the 1913 Winter Egg and the 1914 Mosaic Egg.

1912: Melting Ice Pendant. Drawing of No. 13 from the Jewelry

Book of Albert Holmström (Photograph Wartski) Ice Pendant. Design

Alma Pihl, Workshop Albert Holmström. Provenance the Nobel Family.

(Private Collection. Photograph Katja Hagelstam. Illustrations Courtesy

Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm) 1913 Winter Egg

(Courtesy Wartski)

Mosaic Brooch, ca. 1913 (Formerly Harry Woolf Collection,

Christie’s London, November 29, 2021, Lot 21);

1914 Fabergé Mosaic Egg in the Royal Collection

Moscow Kremlin Egg, by

Fabergé, Workmaster Unknown,

1906. © The Moscow Kremlin

Museums

(Courtesy Victoria &

Albert Museum)

Archival Details

(Fabergé Research Site)

Alexander Palace Egg, by Fabergé,

Chief Workmaster Henrik Wigström

(1862-1923), 1908.

© The Moscow Kremlin Museums

(Courtesy Victoria & Albert Museum)

Archival Details

(Fabergé Research Site)

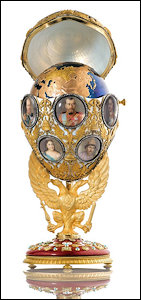

Romanov Tercentenary Egg,

by Fabergé, Chief

Workmaster Henrik Wigström,

1913.

© The Moscow Kremlin

Museums

(Courtesy Victoria &

Albert Museum)

Archival Details

(Fabergé Research Site)

- 1977 – Victoria and Albert Museum exhibition included 20 eggs. Kenneth Snowman’s Fabergé venue honored H.M. Queen Elizabeth’s Silver Jubilee. It was extended for a month closing in October 1977 after 104,000 visitors, some waiting in long queues around the block, had seen it.

- 1989 – San Diego Museum of Art reunited of 27 eggs based on a challenge by the late Malcolm Forbes (1919-1990), a dedicated collector, to Irina Rodimtseva, director of Moscow Kremlin Museums, to match every egg in his collection with one from the Armoury Museum in Moscow.

- 2021 – Victoria and Albert Museum exhibition showcases 15 eggs – an unbelievable feat, and reason to celebrate the first ever reunion of the two Easter eggs presented in 1906, 1908, and 1913 to Maria Feodorovna and Alexandra Feodorovna, the two Russian empresses. And what an opportunity for younger generations to appreciate the art and magic of:

| Fabergé’s Objets D’art | |

|---|---|

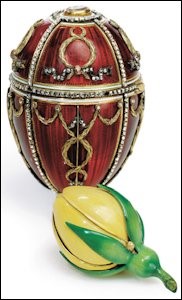

| 1885 First Hen Egg | 1908 Alexander Palace Egg* (illustrated above) |

| 1887 Third Imperial Egg | 1908 Peacock Egg |

| 1892 Diamond Trellis Egg | 1910 Colonnade Egg* |

| 1895 Blue Serpent Clock Egg | 1913 Romanov Tercentenary Egg* (illustrated above) |

| 1901 Flower Basket Egg* | 1913 Winter Egg |

| 1906 Moscow Kremlin Egg* (illustrated above) | 1914 Mosaic Egg* |

| 1906 Swan Egg | 1915 Red Cross Triptych Egg* |

| 1907 Love Trophies Egg (aka Cradle of Garlands Egg) | |

- Archival website about Fabergé Easter eggs gathered meticulously over the years by the late Annemiek Wintraecken, and

- Fabergé Imperial Egg Chronology on the Fabergé Research Site.

Reference publications:

-

Fabergé, Tatiana, Proler, Lynette G. and Valentin V. Skurlov. The Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs, 1997.

Letters written by Tsars Alexander III and Nicholas II, Fabergé invoices, cabinet documents and Bolshevik inventories are the basis for new research by Valentin V. Skurlov of St. Petersburg. This information sheds new light on the history of the Fabergé eggs. -

Lowes, Will, and Christel Ludewig McCanless. Fabergé Eggs: A Retrospective Encyclopedia, 2001.

Monograph gives comprehensive information about 66 Fabergé eggs divided into four categories – Tsar Imperial, Imperial, Kelch and Other. Technical descriptions, all known public exhibitions and auctions through 1997, and reference citations (books, journals, newspapers, and miscellaneous sources) covering the literature of nine countries are given for each egg. Who’s Who in the House of Fabergé profiles 500 artisans and companies who worked for or with Fabergé.

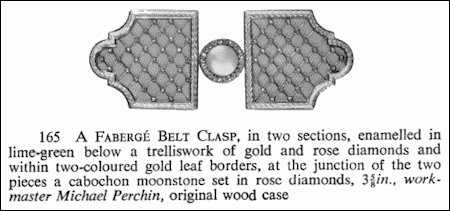

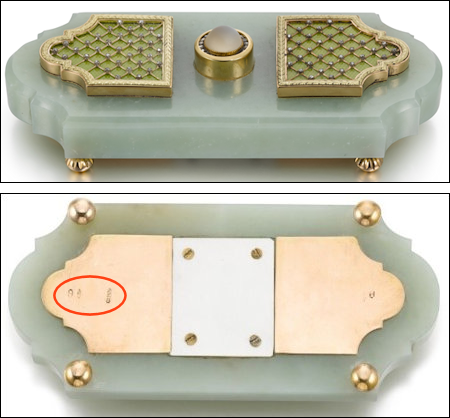

- Clasps or buckles have not been in fashion since the 1930’s, and it is therefore not surprising someone transformed the original item into something more useful. Hence, the bell push, but it would have made more sense, if the clasp had just been turned into two brooches with a left-over diamond and moonstone push piece.

- Unfortunately, neither auction house was aware of the object’s past history.

1961

(Sotheby’s London, March 27, 1961, Lot 165)

2013: 52 Years after the 1961 Auction

Estimate: $1,200-1,800, both objects sold for $43,750

(2021 value – $50,100)

2020: 59 Years after the 1961 Auction

(Sotheby’s London, December 2, 2020, Lot 37)

My observations after the 2020 London auction when the ‘re-purposed’ bell push alone did not sell. It is a somewhat awkward piece and does not resemble any bell push produced by the Fabergé firm:

- The bell push is 5 inches long for a single button bell push. Most original Fabergé bell pushes are 2-3.5 inches square, rectangular, or round, so the proportions are off.

- The bell push was ‘re-purposed’ as an electric one. The wires were not included nor did the author look at the interior mechanism to verify if it was intact when he viewed the object.

- The gold support for the diamond-set moonstone push appears high and envelops the push piece.

- The two diamond encrusted enamel panels were not set flush or below the bowenite base as they should have been. They were raised above the base and there is no harmonious flow to the design.

- All of this makes sense when one discovers the Fabergé object in its original box was originally made to be used as a belt or cloak clasp when it sold at auction in 1961.

- Standing Fabergé thermometer converted into a ‘vase’, and

- Fabergé barometer converted into a clock and … back to a barometer.

The loans for the venue came from the Imperial Russian family, the nobility, and business elite of the time. By an uncanny coincidence, these turn-of-the century weather instruments made between 1887-1899 by the Mikhail Perkhin studio (in existence from 1896-1903) happen to be en suite, and belonged to the collection of Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna (1875-1960), sister of Emperor Nicholas II.

Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna (1875-1960),

Sister of Emperor Nichols II, ca. 1894

(Unknown Author, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

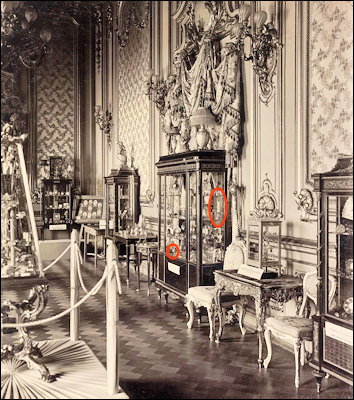

Xenia Alexandrovna’s Vitrine, von Dervis Exhibition, March 9-15 [OS],

1902 (Left) Fabergé Barometer – (Right) Standing Fabergé Thermometer

(von Habsburg, Géza, and Marina Lopato.

Fabergé: Imperial Jeweler, 1993, p. 432, illustration 363)

Fabergé Standing

Thermometer

(von Habsburg,

and Lopato, Ibid.)

Fabergé ‘Agate’ Vase, Stock

Number 58779 Sold for €20,000

(Baltic Auction Group, Tallinn,

Estonia, June 9, 2020, Lot 16)

Edge of ‘Agate’ Vase,

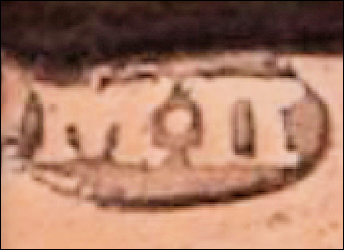

Unknown Perkhin Mark in Beaded Circle

Bowenite Base with Perkhin Partially Cutoff Mark, Post-1895,

St. Petersburg 88 Silver Mark

Typical Post-1895 Perkhin Marks on the Original Thermoter Base – 58779

(Stock Number Toward the End of 1897) Fabergé, Upside-down Workmaster Mark М.П.

(Active 1886-1903), Assay Master Mark – Date, All Applied by Hallmarking Tools.

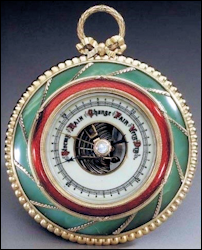

The search for von Dervis exhibition objects in numerous fascinating archival records, auction catalogs from 1934 to the present, and publications after 1917 has yielded interesting results, including our 2007 discovery2 of two missing Imperial Eggs. In the present case study, the second object of interest is a barometer on the bottom shelf of Grand Duchess Xenia’s vitrine. Its journey from 1902 to the year 2000 unveils hallmarks indicating this gilded silver barometer was also made by Mikhail Perkhin before 1899.

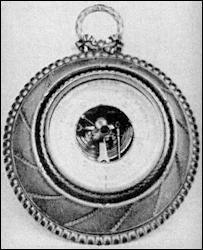

Fabergé Barometer

(von Habsburg, Géza, and Marina Lopato,

Fabergé: Imperial Jeweler, 1993, p. 432, illustration 363)

Fabergé Circular Wall Barometer

Sotheby’s London

June 7-8, 1948, Lot 276

Clock with Hands

Christie’s London

December 18, 1956, Lot 148

- 1948 – first reappeared in its original state as a Fabergé circular wall barometer – at a Sotheby’s London auction (‘the property of a Gentleman’) with the dark finial ‘garnet’ dial also visible in the 1902 von Dervis photograph. Final bid to Wartski £140.

- 1956 – reappeared at Christie’s (‘Property of R.T. Leather Esq.’) converted into a clock with hands which are clearly not the original Fabergé style, price realized £315 (300 guineas) to Manston Graeme, in a leather case.

- 1982 – barometer sold on December 10, 1982, to Ricky di Portanova by British antiques dealer, Wartski.

- 2000 – price realized $21,150 at Christie’s New York auction from the voluminous Ricky di Portanova Collection, re-converted barometer with different features from the original 1902 version: A broader white dial, now bearing English inscriptions in bold letters, and the clear moonstone which replaced the dark ‘garnet’ dial finial. Between 1956 and 1982, the clock was thus removed and replaced by a barometer with a different design than the original one, the restorer presumably being aware of the piece’s original function. The distinctive style of the piece leaves little doubt the Fabergé pieces featured in the collage above are one and the same, and further confirmed by the analysis of the dimensions of the piece in the 1902 photograph which matches the measurements given in the three auction catalogs. Despite being located in different spots in Xenia’s vitrine, these two stunning Fabergé pieces made by Perkhin before 1899 are so closely related in style and combined function of weather gauges, they must have constituted an en suite set. They share in particular a very distinctive tapering circular bowenite base with matching decorations underneath a red enamel band, and are both topped with a laurel wreath.

Neither the barometer nor the thermometer found in Grand Duchess Xenia’s vitrine at the 1902 von Dervis Exhibition are among the Fabergé invoices to Grand Duchess Xenia, all of which are kept in the Russian archives and are now open to researchers. It suggests the Fabergé pair was offered to Xenia Alexandrovna, presumably from the same donor as perhaps a set – otherwise, it would have been quite a coincidence for two identically-styled and related pieces to have been given to the Grand Duchess by two different donors. Being en suite with the thermometer bearing the stock 58779 suggests the wall barometer was given the stock number 58778 or 58780. The stock numbers 58777 and 58781 are a flower and a cigarette case.

Our thanks to James Hurtt, who suggested a possibility for Xenia’s barometer. Is it the one Emperor Nicholas II bought from Fabergé for 270 rubles on May 21, 1899, with the stock number 59810, and has this description: “Barometer, nephrite ring, with gilded silver ornaments Louis XVI, with red enamel and anchor”?3 The bowenite might have been confused for nephrite, and the anchor (not seen nor mentioned in the known pictures and descriptions of the barometer) a decoration referencing the naval career of Xenia’s husband, Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich (1866-1933).

Maybe a stock number can still be found on the barometer, contact: Christel McCanless

1 “Sales of Fabergé & Other Objects from Grand Duchess Xenia’s Palace in the 1920s”, July 22, 2019, Winter Palace Research (Courtesy Joanna Wrangham)

2 Palmade, Anna and Vincent, “Two Lost Fabergé Imperial Eggs Discovered in an Archival Photograph”, Fabergé Research Newsletter, Imperial Egg Discoveries.

3 Guzanov, A. and R.R. Gafifulin, Fabergé Items of Late XIX – Early XX Century in the Collection of the State Museum of Pavlovsk, 2013, entry 4072 for a Faberge purchase on May 21, 1899.

McCanless, Christel Ludewig.

Fabergé and His Works: An Annotated Bibliography of the First Century of His Art, 1994, pp. 34-36.

May 25, 2021 – Andre Ruzhnikov, a dealer in Russian antiques, on his review website for a Christie’s London auction succinctly states the current state of affairs: “I love printed catalogues! They’re great for reference and information, etc. I hope this ill-conceived ‘new beginning’ of Online Sales Only is fleeting, and that catalogues will re-appear soon.” Fabergé researchers and contributors to the Fabergé Research Newsletter agree with this sentiment! In this new digital age, websites and teaser advertisements promoting objects under the hammer, or of a special interest subject area, are the new way of advising collectors/researchers about Fabergé auction lots. One may subscribe free of charge to receive the frequent advertisements via a personal email account.

Other changes along the way:

December 20, 2019 – “Christie’s Is Cutting Its Catalogue Pages and Print Materials in Half Next Year to Curb Its Environmental Impact”. The auction house in its news release states over “52% of lots sold worldwide were purchased by people who did not receive print catalogues. The statistics were even higher 70% for buyers from live auctions.”

Photographs of the objects are not always maintained for longer periods of time. An object at auction may include as many as 20 high-definition photographic illustrations with an automatic zoom feature. But if the object does not sell, the descriptive text and photographs may disappear quickly from the auction’s website. The new owner of an object may also choose not to have an illustration of his object posted.

The two major auction houses, Sotheby’s and Christie’s, both headquartered in London, have closed their Russian departments and no longer offer Russian-themed auctions in New York City.

December 2, 2020 – Sotheby’s, London, announced: “Russian Works of Art, Fabergé and Icons sale will take place as a Live Studio sale, to be conducted by an auctioneer behind closed doors. The sale will offer Advance bidding as well as real-time Telephone and Online bidding.” Prior to 2020, Sotheby’s provided a concise, one-page, listing of lots sold and the hammer price. Now to see the auction results one has to print an abbreviated version of the entire catalog which includes the lot number, photograph of the piece, the estimate, and the price realized. In short, a practical way to participate in auctions is through absentee biding, phone bidding, and through LIVE stream on websites. Each auction house has a set of rules to follow on its website. Online auctions for Fabergé objects are open for bidding a series of days and/or weeks in advance, and after that the records are archived with the price realized by the auction house websites. Unsold lots disappear right after the sale. Sotheby’s offers additional services – new to the auction world.

- Private Sales: Browse a selection of works currently available for private sale

- Buy Now: Shop new arrivals

Christie’s London uses auction techniques similar to its competitor Sotheby’s London. An article dated February 11, 2021, announces “Christie’s Has Closed Off Public Access to Its 255-Year-Old Auction Archive, a Major Resource for Scholars, Citing Budget Concerns.” The library is considered to be the most comprehensive auction archive in the world.

Christie’s website conundrum for Fabergé objects:

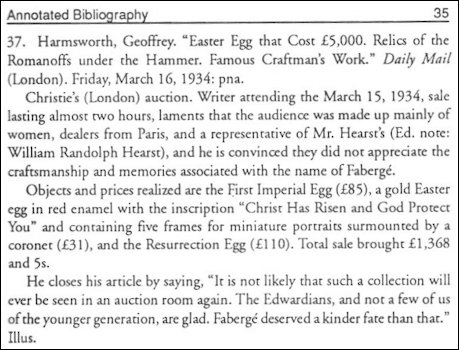

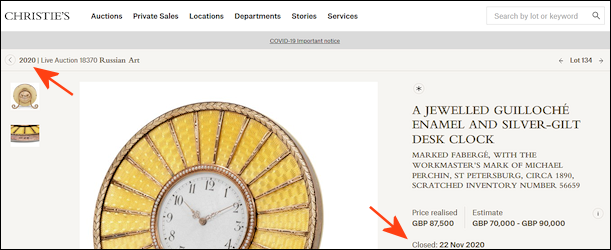

[November 23,] 2020 | Live Auction 18370 Russian Art

Lot 134 A Jewelled Guilloché Enamel and Silver-Gilt Desk Clock, Marked Fabergé, with the Workmaster’s Mark of Michael Perchin, St. Petersburg, Circa 1890, Scratched Inventory Number 56659

Price realized GBP 87,500, Estimate GBP 70,000 – GBP 90,000 Closed: 22 Nov 2020

This is What You See at the Lot Link

This is What You See at the Auction Link

Lot 134 with number 56659 (above) is identified with two auction dates – November 22, 2020 (lower right, closed with date) and on the upper left hand corner there is a 2020 date without a month and a day. A click on 2020 leads to a November 23, 2020 entry which is the final date for the auction. A researcher’s conundrum would be what auction date does one cite in a publication, i.e., in the Fabergé Research Newsletter, or other publications? The answer is one should use the November 23, 2020 date for a research citation. The November 22 date is the closed date when no more bids via fax or e-mail will be accepted. One must register to bid by the November 22, since on November 23, one can bid in person, via online, or telephone. Future researchers may not understand this technique which was already used in 2013 for a two-day sale (Christie’s New York, July 23-24, Lot 159), and is now a digital technique without hard copy catalogs as a primary reference source. The use of additional terminology in order to ascertain correct auction dates would be helpful.

Bonhams London (November 25, 2020) and Bruun Rasmussen, Copenhagen (December 7, 2020) published hard copy catalogs along with their online PDF versions which may only be available from some auction houses immediately after the first sale announcement, or make it yourself. Does Sotheby’s offer this option?

November 20-21, 2021, the Wall Street Journal, headlines its report on the auction activity with this, “The Art Market in Overdrive: Auction Houses Set Record Sales Records … $2.3 billion frenzy of buying and selling.” No mention is made of Fabergé, however, the Woolf Fabergé sale (complete with a limited number of hard copy catalogs) at Christie’s London, November 29, 2021, yielded £5,203,250.

Art libraries, the custodian of auction catalogs for serious collectors and researchers, subscribed to hard copy auction catalogs until the mid-1990s. A difficult problem arose ca. 1995, when auction houses began uploading their auction records to the Cloud. As the cost of Cloud storage began to increase for uploading each new (current year) catalogs, an older year of auction records is taken down. Outcome – older auction records from 1998+ are available electronically at Christie’s, and from 2007 at Sotheby’s. Since auction catalogs are no longer being printed, art libraries had no choice but to discontinue their subscriptions creating large gaps in reference collections. In short, there is a black hole for researchers without auction records on the web – and now, for the most part, no hard copy catalogs after 2019 in libraries, except for the three known exceptions cited above.

In a chat with a Jeff Eger, an out-of-print hard copy auction catalog dealer, he mentioned researchers are using his services for provenance research in hard copy catalogs prior to the year 2020. He maintains one reference copy in his New Jersey warehouse, sells extra copies, or disposes of duplicates, and buys from libraries or collectors who no longer have room to house them, or are too few to be useful. His Fabergé auction catalog holdings are listed here.

Riana Benko supplemented her search for this 2020-2021 Fabergé auction review by using a Russian auction website which includes the two major auction houses, Christie’s and Sotheby’s, and smaller auction houses, all searchable by workmaster, type of objects, etc. Photographs have watermarks and registration is required.

According to the website ARTNET Price Database users may “find over 12 million color-illustrated art auction records dating back to 1985. We cover more than 1,800 auction houses and 340,000 artists, and every lot is vetted by our team of multilingual specialists.” A quick Fabergé search is free, and there are fee-based one day passes, and more options. Users of this website soon learn the data is not as complete as the details found in hard copy catalogs. Beware of Fauxberge and in the style of Fabergé!

A group of newsletter readers, who follow the auction market closely, agreed to discuss a few interesting objects from the Benko list. If there are oversights or additional research observations, please advise. Contact: Christel McCanless

[Electric] Bowenite Bell Push, Mikhail

Perhkin, St. Petersburg, before 1899, Stock

Number 47426, Estimate $20,000-30,000,

Price Realized $25,000.

(Doyle, New York, April 28, 2020, Lot 4)

[Electric] Bowenite Bell Push, Garnet,

Silver-gilt, Steel, Probably Mikhail Perkhin

with French Import Mark, 1899-1908

(Keefe, John Webster, et al. Fabergé:

The Hodges Family

Collection, 2008, pp. 144-145)

[Electric] Bowenite Bell Push, Mikhail Perhkin, St.

Petersburg, ca. 1892, Stock Number 45298.

Purchased by Emperor Alexander III and Maria

Feodorovna, Returned, then Purchased by Three of

Their Children on January 20, 1893, and Given to

Their Parents for Christmas/New Year’s 1892-1893.

Sale Price Stayed the Same at 185 Rubles

(Courtesy Private Collection)

[Electric] Bowenite Bell Push

on Three Feet, Mikhail Perkhin,

Stock Number 50766, Purchased

by Empress Alexandra

Feodorovna for 225 Rubles on

February 28, 1896

(Pavlovsk Entry #3441; Hillwood

Estate, Museums and Gardens,

Washington, DC)

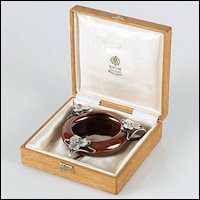

Hagelstam & Co., Helsinki, Auction Ending on June 11, 2020, Silver and Ceramic Ashtray (Lot 1352)

by Anders Nevalainen with 15 Detailed Photographs Sold for €14,000.

(Courtesy Thomas Luoma, Hagelstam Auctioneers)

I decided to include our Russian colleagues in the discussion: Galina Gabriel from the Stieglitz Academy of Art and Industry, and the two scholars and sisters, Galina Korneva and Tatiana Cheboksarova. They soon determined the unclear signature at the bottom of the dish was the well-known M.S. Kuznetsov Company, which by the early 20th was responsible for almost two-thirds of the pottery and porcelain output in the Russian Empire. After a lively discussion, the silver flowers were identified as viola tricolor (Cupid’s delight), a wild pansy with dark purple upper petals, light violet side petals, and a yellowish lower petal. It blooms between May and September and grows in abundance on dry meadows, banks, fields, and seaside beaches in and around the St. Petersburg region. There is a lot of folklore connected to the flower, probably a reason why it was chosen to decorate the ceramic charming dish.

Research by Christel Ludewig McCanless – In the same auction a silver and enamel beaker (Lot 1357) by Henrik Wigström with photographs allowed a potential buyer to examine the piece on-line, since the auction rooms were closed. The Fabergé Schnapps glass with its identified military provenance, in a case before belonging to another prize, and the stock number 11854 sold before:

- June 11, 2020, Lot 1357, €4,000/estimate €3,000

- November 22, 2018, Lot 2023, €7,000/estimate €7,000

- May 7, 2018, Lot 69, two days after the T113 auction website states object sold for €9,500/estimate €7,000 (At newsletter press time, the past auction database suggests this lot did not sell, estimate €7,000.)

James Hurtt, newslettter contributor, in his “interactive” peer review added these observations for the ceramic dish: “A lot of interesting information contained in this article, and love all of the photo images the auction house published.” On the the small beaker with the military emblem attached to the lid of the box there appears to have been stamped the mark used by [Antti Nevalainen – workmaster marks A N and AN ![]() – active 1885-1917] based on the style of the object. When one looks closely at the mark one sees under the Fabergé mark an ‘A’. The N must have been polished away by mistake, or the marking iron slipped.

– active 1885-1917] based on the style of the object. When one looks closely at the mark one sees under the Fabergé mark an ‘A’. The N must have been polished away by mistake, or the marking iron slipped.

Unfortunately, dates when past auctions took place are cited as “auction closed” without specific date details by this auction house – not very helpful for collectors or researchers. The staff at Hagelstam has advised the archival database is being revised, and will be uploaded in its new format at a future time.

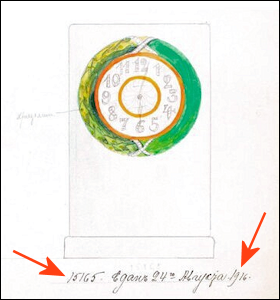

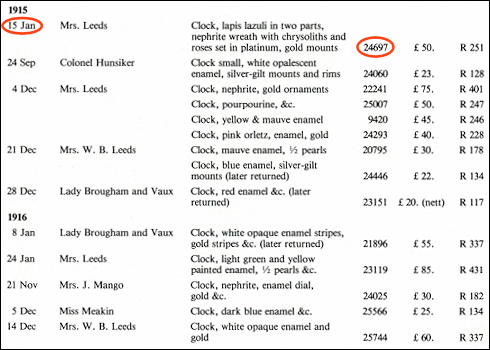

Lapis Lazuli and Nephrite Clock,

Fabergé in Cyrillic, 72 Standard, with

Scratched Inventory Number 24697

(Sotheby’s, London, December 2, 2020,

Brooklyn Museum Sale, Lot 11,

Estimate: 80,000 – 120,000 GBP,

Price Realized 402,200 GBP)

In 1916 an Original Design Sketch with a Production

Number of 15165 for this Fabergé Clock from the

Forthcoming Publication of Henrik Wigström’s Second

Album of Drawings by Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm,

et al. (Sotheby’s Overview, Illustration

Courtesy Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm)

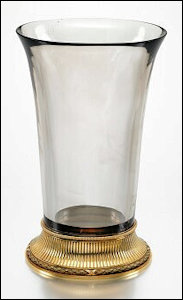

Balleta Vase (Sotheby’s, London,

December 2, 2020, Lot 12,

Estimate: 250,000 – 350,000

GBP, Prize Realized 934,600 GBP)

Entry from the Official London Sales Ledgers

(von Solodkoff, Alexander. Fabergé Clocks, 1996, p. 42)

- The matching stock number 24697 for the Leeds/Brooklyn Museum clock sold in January 15, 1915, for £20 would have been made in 1914, and therefore, predates the Wigström design sketch dated 1916.

- Mrs. Leeds bought five clocks from the London branch in 1915-1916.

- The design sketch illustrated next to the Leeds clock is dated 1916, and is incorrectly attributed to be “the original design for this clock, recorded under number 15165” in the overview of the Sotheby’s London, December 2, 2020, auction. Design and production sketches are a separate numbering system from stock numbers. (Adams, Timothy, “Fabergé Design Sketches and What They Teach Us”, Fabergé Research Newsletter, Fall and Winter 2018)

- Kieran McCarthy in his book, Fabergé in London: The British Branch of the Imperial Russian Goldsmith, 2017, states the last shipment of merchandise from St. Petersburg to London was in June 1914.

- Sotheby’s auction entry calls the jewels studding the jade wreath peridots, yet they are demantoid garnets. Much later in another description, the correct name is given.

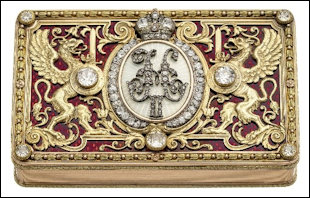

Imperial Presentation Box Made in 1897 by Fabergé Workmaster Mikhail Perkhin in St. Peterburg

Sotheby’s London, Estimate GBP 150,000-200,000, Price Realized GBP 200,000/$270,000 June 15, 2018, Lot 344

Piguet, Geneva, Estimate CHF 100,000-150,000, Price Realized CHF 170,000/$192,000, December 8, 2020, Lot 216

(Illustrations Courtesy Piquet, Geneva)

Original provenance: Presented to First Lieutenant-General Théodor Feldmann, Head of the Imperial Alexander Lyceum on December 3, 1897, who returned the box to the Imperial Cabinet in exchange for the monetary equivalent, an option of the day in Imperial Russia. Two years later on November 15, 1899, the box is presented to Baron Maximilian von Lyncker, House and Court Marshall of noble rank for Kaiser Wilhelm II. In 1966, its discovery in a Swiss safe begins another life for the box. The center medallion with the diamond cypher of Nicholas II is topped by an Imperial diamond crown. The large diamonds used in the piece indicate the importance of the recipient(s).

The complex gold and enamel work on the box created in the workshop of head workmaster Mikhail Perkin (active 1886-1903) features his often-used technique of gold appliqué or cage-work over guilloché enamel. The rich translucent strawberry red enamel is laid over an engine-turned ground, and then elaborate gold appliqué designs with acanthus leaves, vine tendrils, two griffins rampant with swords and shields are added. It is a rare example of the Romanov family emblem (the griffins with swords) used instead of the State emblem of the double-headed Imperial Eagle. The quality of the chasing and engraving of the gold displays the attention to detail Fabergé’s workmasters strove for in their work. The gold appliqué serves two purposes – one is purely decorative, and the second keeps the enamel surface from being scratched, or worn away over time. The use of multi-colors of gold add to the richness of the box, while the green and pink gold floral and dot border is a delicate complement to the bold center design.

James Hurtt noticed two different stamps by Mikhail Perkin on this box – an earlier one used before 1895, and a later stamp Perkin used after 1895. A discussion among the essay contributors brought forth a possible explanation. Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm’s theory:

CLICK THE ABOVE PICTURE FOR A LARGER VIEW

Varicolored Gold-Mounted Nephrite Desk

Set, Workmaster Henrik Wigström, Collection

of Baron Hans Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza

Sold for 571,600 GBP

(Sotheby’s, London. Treasures,

December 10, 2020, Lot 34)

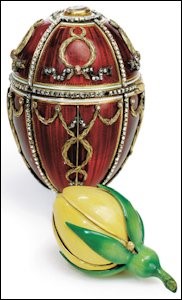

Rosebud Egg in the

Forbes Magazine Collection

(Courtesy Fabergé Museum,

St. Petersburg, Russia)

In 1987, the Baron hosted the Forbes Magazine Collection in his Villa Favorita, Lugano, Switzerland. In the foreword to the exhibition catalog (Fabergé Fantasies: The Forbes Magazine Collection, p. 7), he writes about his Fabergé objects, “… as a Fabergé collector, 20 years younger than Mr. Forbes … Today I own altogether 24 examples … among them a twelve-piece set of jade in the Louis XVI style, while Mr. Forbes has over 300 pieces … mine may seem rather marginal.”

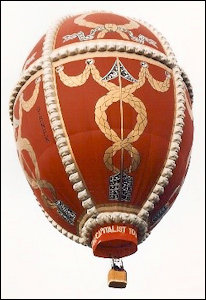

Long time Fabergé enthusiasts may recognize the Rosebud hot air balloon shown above. Another passion of long-time Fabergé collector and balloon enthusiast Malcolm Forbes (1919-1990), added quite a bit of excitement (when the winds were just right!) to several Fabergé exhibition events in Lugano, Switzerland, San Diego, and Moscow during the years 1987-1990. The Lugano exhibition (April 14 – June 7, 1987) featured 134 objects from the Forbes Magazine Collection.

Fabergé Hardstone and Gold Inkwell, Mikhail Perkhin, St. Petersburg, 1886-1895. Stock Number 43799

(Bukowskis, Stockholm. December 10-11, 2020, Winter Sale 629, Lot 226)

January 11, 2022, press release states “Bonhams Announces Acquisition of Bukowskis”, the leading auction house in the Nordic region. Bukowskis Auction House history: “On 22 April 1870, the Polish nobleman Henryk Bukowski received the official permit from the Stockholm Governor’s Office stating that as a foreigner he could trade in works of art and antiques – this date is considered to be the beginning of the activity of his company, Bukowskis. (Courtesy Wikipedia)

A review of the successful auction was written by Andre Ruzhnikov. Some objects still in the Woolf Fabergé Collection are on view at the Victoria and Albert Museum until the venue closes on May 8, 2022.

- Christie’s Geneva, November 18, 1980 (Collection of Josiane Woolf, Part 1)

- Christie’s Geneva, May 12, 1981 (Collection of Josiane Woolf, Part 2)

- Christie’s New York, April 19, 2002

- Wartski, London, Carl Fabergé: A Private Collection, 2012

-

Biographical story of the collectors:

Harry and Josiane Woolf

(Courtesy Christie’s London, November 29, 2021, pp. 6-7)

The special relationship between Harry Woolf and Fabergé dates back to the 1970s. Harry, Chairman of the successful London based pharmacy chain, Underwoods, subsequently sold to Boots in 1988, visited his newly retired father who was choosing to while away his days in front of some pretty average television shows.‘I determined there and then to find a hobby, said Harry – so that my mind would be more satisfactorily occupied at a similar age’. He duly met a string of London dealers who worked in spheres as diverse as early clocks and contemporary art. None sparked much interest. Then, one night, a guest at a dinner party at his house in Hampstead posed the fateful question: ‘Why not Fabergé?’

Harry was immediately attracted. In part because the jewelery house – like his paternal grandparents – were Russian; and in part by the stunning workmanship of the object he was shown.

He soon started researching Fabergé and consulting experts before embarking on a passionate collecting mission that lasted the best part of 50 years. Harry passed away in November 2019 and just 5 days before he was still buying pieces.

He was a generous lender to Fabergé exhibitions around the world, the excellence of his objects was highly sought after. The range in the collection being breathtaking, including, as it does, examples of all the renowned fields of Fabergé craftsmanship: from animal figures and photograph frames to perfume bottles, flower studies and brooches.

It is a collection that surpasses all the prestigious examples previously sold at Christie’s: the Kazan (1997) and di Portanova (2000) collections, to name but two. With specific regard to the animal figures, only the British Royal Collection can be considered comparable.

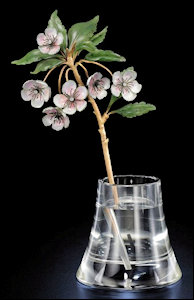

The House of Fabergé was issued a royal warrant by Emperor Alexander III in the mid-1880s, and its objects were soon must-haves among Europe’s elite, routinely serving as diplomatic gifts. One of the true highlights of the Woolf collection is an intricate, trompe l’oeil study of a wild strawberry plant in a vase of water. A similar flower study is part of the British Royal Collection.

Harry was never one to follow trends. Everyone in the Fabergé market – dealers and auction house specialists alike – knew better than to steer him towards particular works. He preferred to rely almost solely on his instinct, taste and finely attuned eye. The end result was one of the most iconic Fabergé collections in private hands.

Lot 405

Fabergé Jeweled Gold-mounted

Guilloché Enamel, Rock Crystal and

Nephrite Model of an Apple Blossom

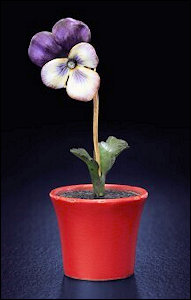

Lot 406

Fabergé Jeweled Gold-mounted en plein Enamel,

Rock Crystal and Nephrite Model of a Violet

Lot 407

Fabergé Jeweled Enamel and

Hardstone Study of a Pansy,

Workmaster Henrik Wigström

(Courtesy Sotheby’s London,

November 30, 2021)

A quick look at the Fabergé bibliography on the Fabergé Research Site suggests these standard works have chapters about flowers. Please note after 2007 chapter headings are no longer cited in the bibliography listings:

- Bainbridge, Henry Charles. Peter Carl Fabergé: Goldsmith and Jeweller to the Russian Imperial Court and the Principal Crowned Heads of Europe, 1949.

- Snowman, A. Kenneth. The Art of Carl Fabergé, 1953.

- Lesley, Parker. Handbook of the Lillian Thomas Pratt Collection: Russian Imperial Jewels, 1960.

- von Habsburg, Géza. Fabergé, Juwelier der Zaren (English title: Fabergé), 1986.

- Hill, Gerard, et al. Fabergé and the Russian Master Goldsmiths, 1989.

- Keefe, John Webster. Masterpieces of Fabergé: The Matilda Geddings Gray Foundation Collection, 1993.

- von Habsburg, Géza, et al. Fabergé: Imperial Craftsman and His World, 2000.

- de Guitaut, Caroline. Fabergé in the Royal Collection, 2003.

- Reed, Joyce Lasky and Marilyn Pfeifer Swezey. Fabergé Flowers, 2004.

Visit in Grand Place, Brussels: Jean-Jacques

Wintraecken with Farah

and Annemiek Wintraecken

(Photograph Courtesy Ms. Hoff)

Two interesting essays with news about Fabergé egg surprises appear in this edition of the Fabergé Research Newsletter.

(A.) 1885 First Fabergé Imperial Egg

(Courtesy Fabergé Museum,

St. Petersburg, Russia)

(B.) Danish or Rosenborg Egg (Golden Egg with Hen)

in the Danish Royal Collection, ca. 1720

(Courtesy Fabergé Chamber, Amalienborg Museum)

(C.) Golden Egg with Hen (Green Vault Egg), ca. 1720 (McCarthy, Kieran, and Hanne

Faurby. Fabergé: Romance to Revolution [2021], pp. 207-209, 226, pl. 180; Photograph

Courtesy Grüne Gewölbe Museum [Green Vault Museum], Dresden, Germany)

The Green Vault Egg (C.) – In 1988 another, virtually identical example, was consigned by the widow of Prince Ernest of Saxony, youngest son of Frederick Augustus III of Saxony, the present author’s uncle, to the auction house Habsburg Feldman, Geneva4. At the time Joachim Menzhausen, curator of the Dresden Green Vault, identified the object has having been formerly owned by Augustus the Strong, Elector of Saxony, King of Poland, and listed in the Saxon Royal Collection with Inv. Nr. VI, XIII. Exhibited to the general public for centuries as a curious attraction, the egg was thus accessible to Carl Fabergé (1846-1920), presumably a regular visitor to the museum until the death in Dresden of his father, Gustav, in 1893, when his visits may have ceased. In 2004, research by Dirk Syndram, then curator of the Green Vault, revealed the Dresden Egg was acquired by Augustus the Strong at the Leipzig Fair in 1705.5 In 2021, the Dresden Egg was offered privately to the Green Vault Museum (Grüne Gewölbe Museum in Germany) and acquired amidst fanfares by Dirk Syndram for €200,000 with the aid of the Siemens Foundation. The headline in the prestigious German newspaper, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitschrift6, is titled “Die Krone in der Henne im Ei” (the crown in the hen in the egg) with an article by Andreas Platthaus, and a large color illustration subtitled “possibly the prototype for Fabergé’s Easter eggs”. The possibility of a connection between the Dresden Egg and Fabergé’s 1885 Egg was first mentioned in 1999 by Mogens Bencard, Keeper of the Royal Danish Collections.7 The present author shared this opinion in the Fabergé Research Newsletter, Fall 2013, and more recently in the publication accompanying the 2021-2022 Victoria & Albert Museum Fabergé exhibition8.

Other recorded prototypes:

The Habsburg Egg – Yet another very similar early 18th century egg is known in the Habsburg Imperial treasury at the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. Both the Danish and the Habsburg examples were exhibited side by side as alternative prototypes together with Fabergé’s First Hen egg in the 1986 exhibition held in Munich.9

The Baden-Baden and Sachsen-Coburg-Meiningen Eggs – Two further similar eggs are known through period inventories and descriptions, one in the Baden-Baden margravial treasury, another formerly in the Sachsen-Coburg-Meiningen collection.10

A second Danish Egg – Another similar egg is recorded in the Danish Royal collections as having belonged to Queen Anna Sophie, neé Rewentlov, second wife of King Frederik IV, mentioned in her diary on June 26, 1722: “A golden egg, wherein a hen, and in the hen a motto with small diamonds”, and later described: “One gold egg, wherein is an enamelled gold hen; within the hen is a seal with a royal crown and 40 small brilliants, 6 small rose-cut diamonds, 5 pearls and a red cornelian engraved with a motto”.11 The differences between the Rosenborg Egg and this description led Mogens Bencard to believe there were two eggs in the Danish Royal Collection. All 18th century eggs must have been considered by their owners as precious, fascinating curiosities, and by general agreement were probably produced in the same workshop.

(D.) LEFT: Oval Agate Casket with Enameled

Silver-gilt Mounts, Attributed to the Jeweler Le Roy,

ca. 1700 (Green Vault Museum, Dresden)

RIGHT: 1894 Renaissance Egg by Fabergé

(Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg,

Photograph Géza von Habsburg)

(E.) Object of Vertu by Moritz Elimeyer, with a Ring, Set with One Sapphire and Numerous Diamonds in 14k Gold.

(Schloss Ahlden auction, May 18, 2019, Lot 2738; Courtesy Géza von Habsburg)

The Elimeyer Egg – A mid-19th century gold egg coated in white enamel and containing a jeweled hen and sapphire ring in its original fitted case stamped Elimeyer, Dresden, was sold at a Schloss Ahlden auction, May 18, 2019, Lot 2738. The gold- and silversmith Moritz Elimeyer (1810-1871) was Goldsmith and Supplier to the Saxon Court, as well as to Queen Victoria. This egg too, attests to the popularity of the Green Vault Egg in Fabergé’s time. I thank my colleague Alexander von Solodkoff for alerting me to the Schloss Ahlden auction and for researching this egg.

Another Candidate?

At a recent exhibition at the State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, a new candidate was presented as Fabergé’s First Egg which engendered a lively discussion about the 1885 egg and its origin. The owner of this egg, a Russian businessman, had first loaned it to the Fabergé Museum in Baden-Baden, Germany. Despite requests, no Western Fabergé specialist has been authorized to examine this egg. However, its style, surprise (it contains two miniature ruby pendants), and its all-to brief history with an 1898 date, have turned most Fabergé experts firmly against it.13

1 Fabergé, Tatiana, Proler, Lynette, and Valentin Skurlov. The Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs, 1997, p. 94, note 86 (quoted from a letter in the Tatiana Fabergé Archives)

2 Snowman, A. Kenneth. The Art of Carl Fabergé, 1962, pp. 76, 78, 142-143. (A revised and enlarged edition with new information was published in 1962. All subsequent editions and impressions are reprints of this edition.)

3 Bencard, Mogens. The Hen in the Egg: The Royal Danish Collections, 1999, pp. 30 ff. (“The Danish Egg and Fabergé’s Imperial Eggs”)

4 Habsburg Feldman, Geneva, November 16, 1988, Lot 255.

5 Syndram, Dirk. Schatzkunst der Renaissance und des Barock, 2004, p. 15, note 2.

6 FAZ Feuilleton, October 19, 2021, Nr. 243, p. 9.

7 Bencard, 1999, p. 34.

8 von Habsburg, Géza, “The Legacy of the Imperial Easter Eggs” in Fabergé: Romance to Revolution, [2021], pp. 207-209, 226, pl. 180.

9 von Habsburg, Géza, Fabergé, Hofjuwelier der Zaren, Hirmer Verlag, 1986, cat. 532, 662-663. A German edition was published by Habsburg Feldman Editions, in 1987.

10 Bencard, 1999, p. 28.

11 Bencard, 1999, p. 21, note 8; Berner Schilden Holsten, Henrik. Dronning Anna Sophie paa Clausholm, 1911, p. 42.

12 von Habsburg, 1986, cat. 538, 661.

13 The Art Newspaper, March 17, 2021: “Hermitage Director Responds to Accusations of Fakery in Fabergé Exhibition”.

Lapis Lazuli Egg with the Crown and Ruby Surprises,

Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio

(Courtesy Peter Carl Fabergé, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons)

Lapis Lazuli Egg and Surprises Similar

to 1920’s Wartski Archival Illustration

(Photograph Courtesy Chad Solon)

1895 Rosebud Egg with Its Crown, Ruby Pendant Surprise, and Rosebud

(Courtesy Wartski 1920 Archival Photograph)

Lapiz Lazuli Egg Crown and Ruby Pendant Surprises,

Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio

(Courtesy Peter Carl Fabergé, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons)