(A.) H.M.S. Talbot Kovsh (56 cm across/22 in.)

(Courtesy Trophy Collection of the Royal Navy, Portsmouth, UK)

(B.) U.S.S. Mayflower Kovsh

(19.25 in. high/48.9 cm)

(Courtesy U.S. Naval Academy Museum,

Annapolis, Maryland)

(C.) French Battleship Vérité Kovsh

(54 x 60 x 32 cm/21 x 24 x 13 in.)

(Zeisler, Wilfried. “Cadeaux des

Tsars. La Diplomatie Navale dans

l’Alliance Franco-russe, 1891-1914”,

Neptunia Special Issue. Musée

National de la Marine, Paris,

May 2010, 34/35.)

We begin with the H.M.S. Talbot Kovsh (A.), one of three Naval presentations and the earliest in our study of large silver kovshes created by Fabergé’s Moscow artisans. Currently preserved in the Trophy Collection of the British Royal Navy at Portsmouth, the kovsh is blessed with a lineage further identified beyond its date stamp for 1899-1908. It is inscribed: Presented by the Emperor of Russia to the Wardroom of H.M.S Talbot in friendly recognition of the assistance rendered to the crews of the ‘Variag’ and the ‘Koreitz’ after the Battle of Tchemulpo. February 1904. The presentation date allows us to narrow the year of production to 1899-1904.

We remain by the sea and are again linked to Portsmouth (New Hampshire this time) for our second case study. The Russian defeat in the war against Japan ended with the signing of a peace treaty there aboard the U.S.S. Mayflower in 1905. This kovsh (B.) was presented to the wardroom mess of the historic vessel and is preserved at the Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. The Russian dedication translates “To the Hospitable Yacht Mayflower as a Token from the Russian Delegates to the Peace Conference at Portsmouth, August 1905”. With the same year stamp for 1899-1908 as the Talbot Kovsh, the dedication in 1905 narrows the production to 1899-1905.

A third kovsh (C.) with Naval ties connected to the French battleship Vérité is preserved at the Musée de la Marine in Paris. The date stamp now moves to the 1908-1917 mark with the donation confirmed for 1908, thereby making it the year of production. The kovsh was probably mounted on a plinth which has now been lost. Thankfully, the original dedication plaque in French is extant and reads “Offered by the Emperor of Russia to the officers of the battleship ‘Vérité’ – Revel, 15/28 July 1908”.

(D.) Bogatyr Kovsh

Formerly in the Forbes

Magazine Collection

(23 1/8 in. high/59 cm)

(Courtesy

Sotheby’s New York)

(E.) Decathlon Trophy for the 1912 Olympic

Games in Stockholm

(47.5 x 59.8 x 31 cm/19 x 24 x 12 in.)

(Courtesy Olympic Museum, Photograph

© IOC/Jean-Jacques Strahm)

(F.) Nobel Family Falconer Kovsh

(21 in./53.3 cm wide, 125.28 oz./3896.5 grams of silver, gross)

(Courtesy Christie’s London)

The Decathlon Trophy (E.), also a kovsh, was presented to the winner of the sporting event at the 1912 Olympic Games in Stockholm. Although the Moscow hallmark offers 1908-1917 as general dates, 1910 may soon be confirmed since the kovsh’s scratched inventory number 18831 was recently cross-referenced in preparation for this article. An Imperial Cabinet invoice citing the cost as 2500 rubles and countersigned by Nikolai Rakhmanov on May 18, 1910, is extant.

Although not strictly speaking a bogatyr design, it seems appropriate to include the Falconer Kovsh (F.) created by Fabergé Moscow in 1899-1908 and owned by the shop’s prominent patrons, the Nobel family. The scratch inventory number 24682 on the piece may shed further light on its commission. For now the engraving of 23/x/1909 is the only clue. The Falconer Kovsh serves as a transitional link to discuss the final bogatyr kovsh in this study which was a gift to the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts by Jerome and Rita Gans (G.). It is the largest and most complex of our series and marked for Moscow 1899-1908 with an additional French control mark perhaps reframing the dating for this piece.

Further research into these and other surviving monumental kovshes will reveal insights into the evolution of the neo-Russian strand of the Art Nouveau and how it fits into the silver production of the Moscow branch. As specific design and dating come into focus, we may be able to trace anonymous makers and their specific influence. Over the course of the next few issues, we will more closely examine each kovsh through both historical and stylistic lenses and its archival data. We look forward to engaging the wider Fabergé Research Newsletter community in these discussions. Contact: Cynthia Sparke

The stylistic advent of these works began in 1703, when Peter the Great set about transforming a swampy marshland captured from Sweden into the city that would bear his name. The strategic port of St. Petersburg provided access to the Baltic Sea and aspired to be a glittering “Venice of the North.” This enticing new market drew foreign purveyors of luxury goods to Russia including the eclectic jewelry maker, Gustav Fabergé (1814-1893). In 1842, he founded a jewelry firm in his name. Eighteen years later, Gustav was in a position to retire abroad and leave the Fabergé firm in trusted hands until his son Carl (1842-1920) had completed his studies, was of age to return to St. Petersburg, and to take the helm in 1872. By the mid 1880’s, Carl had secured the family firm’s reputation in the Imperial capital, delighting its St. Petersburg clientele with a vast array of sophisticated trinkets largely inspired by what was in vogue in Western Europe. These evoked earlier styles such as the Rococo or Neo-classical, which were then re-interpreted by the firm’s designers to suit Russian gentility in rosier tones of gold and a wide palette of guilloché enamels.

Moscow Revival

Meanwhile, Moscow’s prominence was resurging as an epicenter of the textile trade and a railway hub for a transportation network expanding across a vast Empire. Fortunes were being made there, crafts people and suppliers were attracted to this rapidly expanding market, and the supply of talented silversmiths drawn to the city was higher than in St. Petersburg and the costs associated with silver production were lower. Moscow provided both cost-effective supply and increasing demand, leading Fabergé to open a branch there in 1887 to satisfy the growing appetites of a burgeoning middle class. Buried within an early account of the firm’s Moscow production are a striking number of clues which help shape our understanding of how the branch differentiated itself from the flagship headquarters. Henry C. Bainbridge (1873 or 74-1954) published the groundbreaking biography of Peter Carl Fabergé in 1949 having served as manager of the London branch (sales only) from 1903-1915 and he knew the Russian owners personally. While the monograph was authoritative and for decades served as a stand-alone resource well before the modern flurry of interest in Russian decorative arts, it is from this nostalgic vantage point that Bainbridge recounted his understanding of the firm in florid and sometimes deferential terms.

(G.) Russian Style Kovsh, Gift of Jerome and Rita Gans

to the Museum

(69.8 cm /27.5 in. long, 400 oz./12,455 grams = 25 lbs.)

(Courtesy Virginia Museum of Fine Arts)

(H.) Miniature of the Russian State Regalia,

Platinum and Diamonds by Fabergé, 1900

(Courtesy Royal Russia and Wiki)

François Birbaum (1872-1947), Fabergé’s chief designer in St. Petersburg, recounted in his memoirs that while the Russian style predominated in the branch’s production, the compositions were kept fresh and free of clichés. “Figures of heroes, folk poems and tales, historical events or people all served as subjects – as separate figures of groups or in bas relief on the objects themselves. The works are mainly cast from wax models and one object only was produced from each model.”iii

With its Moscow launch, the company entered a market favored by Russia’s rich heritage over Parisian dictates for stylistic inspiration. When Moscow’s intelligentsia searched for an aesthetic language reaching back to a time before Peter the Great’s reforms, incentive arose to re-acquaint themselves with long lost artisanal traditions.iv The generation of Fabergé designers who defined the Moscow style looked to a variety of influences to help define a grammar of ornament and to interpret them to a high standard.

Specific resources contributed to expressing Old-Russian Style in silver. These ranged from exploring native heritage through increasingly available print sources and from studying preserved artifacts themselves. Rural craft traditions were being regenerated in cottage industries. With the encouragement of generous patrons, exhibitions and retail outlets were secured for these applied arts and their fame and understanding flowed back into Moscow workshops. In order to hone the design and production of decorative arts and widen their appeal, it became clear targeted coursework in draftsmanship and technique was required.

Fabergé’s Moscow Style

The most prominent training grounds for ceramics, silver design and stylistic studies were the Stieglitz School of Technical Drawing and the Society for the Encouragement of the Arts both in St. Petersburg. The Imperial Stroganov Central Industrial Art Academy in Moscow played a pivotal role in defining a distinctive Moscow style for the firm. The school served as an innovative advocate for a return to native Russian ornamentation, which then filtered through to Fabergé designs, experimental techniques and materials produced in the Moscow workshops. The Stroganov School gained a reputation for its experimental ceramics innovating new glazes that suggested gemstones or metal and those techniques were then applied to Fabergé projects once trainees joined the firm. When graduates qualified as professors, they could contribute to special commissions or supply designs for Fabergé’s Moscow branch so there was an established collaboration between the Stroganov School and the Fabergé firm.

The resurgence of Rurik era craft traditions found crucial support from influential patrons. On Russian soil one of the most prominent industrialists taking an interest in preserving traditional culture was Savva Mamontov (1841-1918). Heir to a vast industrial fortune, he was well-positioned at his estate of Abramtsevo near Moscow to observe how Russian traditional craftsmanship and folklore were losing ground to efficiency and economy of mass production, and the young and able were increasingly abandoning the country in favor of factory jobs in the city. Mamontov and his wife Elizaveta played a crucial role in establishing Abramtsevo as an artistic colony in the late 19th century and invited Vasily Polenov (1844-1927) and Viktor Vasnetsov (1848-1926), and other distinguished artists to collaborate on projects for the church and out-buildings. The colony also incorporated workshops directed by Vasily’s sister, Yelena Polenova (1850-1898), to revive traditional woodwork, ceramic and textiles.

New Russian Style

By the beginning of the 20th century, the new Russian style integrated Art Nouveau elements from the west and was termed Styl’ Modern. Confusingly, this particular term incorporated two distinct strands, one remaining more faithful to Western Art Nouveau and the other incorporating Russian traditional motifs and termed the neo-Russian style.

In 1900, the Exposition Universelle in Paris featured objects from artist colonies like Abramtsevo and Talashkino displayed in a traditional rural log cabin, the Russian izba. This display resonated with international visitors whose own countries were reviving crafts traditions. News of the Russian exhibits spread abroad, the European appetite for the Art Nouveau travelled back into Russia. Foreign art journals disseminated the new aesthetic to an admiring Russian readership and, in turn, inspired Russian publications to spread the merits of the modern style domestically.

This climate of international reciprocity benefited Carl Fabergé, who established a business empire founded upon a unique grasp of design, technique and commercial expertise. Therefore, the firm progressed well beyond supplying fashionable goods to creating trends by determining what their fickle clientele required in terms of novel and beautifully crafted status symbols. By 1900, the brand exemplified Russian luxury and Fabergé was invited to participate in the Exposition Universelle as a juror. Not only did he obtain permission to exhibit three or possibly five of his famed Imperial eggs at the Paris exhibition, but the Imperial Cabinet approved the display of Fabergé’s miniature replica of the Russian State Regalia (H.) winning a gold medal for participating without competing. The novelties he brought along to amuse foreign visitors sold out and the firm’s reputation further expanded. Eventually, retail outlets established by Fabergé operated from St. Petersburg, Moscow, London, Kiev, and Odessa supplying goods sent to the Far East and Asia to meet the demands of an international clientele.

In trying to reconstruct the trajectory of Fabergé objects from Russia and into collections across the globe during the late Imperial period, modern research is filled with challenges. Following the revolution, many items were sold or destroyed leaving incomplete inventories and sales ledgers, and limited surviving archival material to fill in the blanks. The inherent difficulty in pinpointing the exact date of production for silver objects struck with marks that broadly fall into two eras, 1899-1908 or 1908-1917, invites further investigation. We are more fortunate with St. Petersburg objects, usually hallmarked for their specific workmasters and sometimes scratched with inventory numbers, to cross-reference them with a few extant firm ledgers. Moscow pieces were not generally marked with the symbol of the individual maker but, rather, carried the Fabergé brand name. Relatively little is known about the individual makers involved with this output, so a closer look at a group of objects created in Moscow seems appropriate hoping themes and patterns may emerge.

i Pre-Petrine refers to the era before the reforms of Peter the Great.

ii Bainbridge, Henry Charles. Peter Carl Fabergé, 1949, 133-134.

iii François Birbaum in Habsburg, Géza von and Marina Lopato. Fabergé: Imperial Jeweller, 1993), 448.

iv Today docents at the Catherine Palace outside St. Petersburg raise similar concerns as artisans report a pressing need to engage a younger generation in the “crafts” which

originally built the imperial structures currently being preserved and restored.

v This period of Russian history was founded by Prince Rurik of Viking extraction, whose dynasty ruled Kievan Rus land, later the Grand Duchy of Moscow from the 800s AD onward.

The auction house, Christie’s London, advises “their dedicated sales of Russian Art will now be held twice a year in London, and they will be offering Russian Works of Art, including Fabergé within the context of our Private & Iconic Collection sales in New York”. Inquiries will be managed by the Works of Art Specialists based in London, who will also travel throughout the Americas.

Fabergé Sandstone Match Holder

in the Form of a Rhinoceros

(The de Guigne Collection)

Nephrite Study of a Lily of the Valley Leaf by Fabergé

(Joan Rivers Collection)

Christie’s auction schedule:

- New York – March 24, 2016 Legacy & Heritage: The de Guigne Collection

- New York – April 13, 2016 The Exceptional Sale

- London – June 6, 2016 Russian Art

- New York – June 22, 2016 Property from the Collection of Joan Rivers

Observations and discoveries shared by Newsletter readers:

1890 Danish Palaces Egg

Coryne Hall from the UK writes that she was very interested in the Danish Palaces Egg update. In particular, she comments on the statement, “The scenes depicted on the miniatures were places familiar to Marie Feodorovna, and the yachts she used to travel in. For many years, the third panel of the Egg was wrongly identified as the estate of Hvidøre [more correctly Kejservilla].” Mrs. Hall has been inside both the Kejservilla and Hvidøre, the latter now owned by a company, not a private individual.

Her in-depth research on these residences include:

Hall, Coryne, Little Mother of Russia, 1999, was among the first publications to point out the incorrect identification of the Kejservilla at Fredensborg as Hvidøre (see notes to chapter 10). Two articles both published by Royalty Digest on the Kejservilla in the early 2000’s – “Our Dear Miniature Gatchina” and “A Peep Inside the Kejservilla”. She adds, “I have many documents in Danish relating to the purchase and eventual sale of the property and am in touch with the current owners, helping them research further the history of the property.” Her website also lists her publication, Hvidøre: A Royal Retreat, 2012.

1892 Diamond Trellis Egg

From the Royal Collection website:

Will Lowes, independent researcher writes:

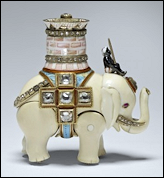

This rudimentary mechanical elephant may well be the first automaton made as a surprise for an Imperial Easter Egg. Compared with the automata made for the 1906 Swan Egg and the 1908 Peacock Egg, this early example lumbers clumsily, and lacks the finesse of the later examples. Still, it is another example of a new idea from the House of Fabergé which, over time, would be honed to perfection. However, the Diamond Trellis elephant may have a particular and unique value, if it proves to be the first Imperial egg automaton.

Diamond Trellis Egg Surprise (1892) and Automated Elephant (ca. 1900)

(Courtesy Royal Collection)

1900 Kelch Pine Cone Egg

(Fabergé, Tatiana, et al. The Fabergé

Imperial Easter Eggs, 1997, 73)

Annemiek Wintraecken, independent researcher, has posted her study on egg automatons.

1914 Mosaic Egg

Roy Tomlin, independent researcher, discovered a video about this egg narrated by Caroline de Guitaut, Senior Curator of Decorative Arts, Royal Collection.

(Updates are posted in Exhibitions on the Fabergé Research Site)

Temporary Fabergé exhibitions to include in your 2016 travel plans:

Folding Screen with Fabergé and Other Pendant Eggs

(Courtesy Photograph © David Hall, Hessischen Hausstiftung, Eichenzell, Germany)

Fabergé Aluminum Kettle

(Courtesy Russian National Museum)

- December 11, 2015 – April 3, 2016 Turku Castle, Turku, Finland

Imperial Gifts from Pavlovsk Palace

More than 150 items from the Pavlovsk State Museum collection in Russia are on display including objects from porcelain dinner services, cigarette cases and snuff boxes, fans, figurines, decorative articles and portraits, and items created by masters of the House of Fabergé. The venue opens next at the South Karelia Museum in Lappeenranta, Finland. Catalog produced. - December 30, 2015 – June 26, 2016 Fabergé Rooms of the General Staff Building, Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Fabergé in the Great War

The display of 43 Fabergé items in the just-opened rooms are a loan from the Russian National Museum in Moscow. (Courtesy Royal Russia, Wednesday, December 30, 2015) - January 22 – April 17, 2016 Reading Public Museum, Reading, Pennsylvania

The Tsars’ Cabinet: Two Hundred Years of Russian Decorative Arts under the Romanovs

Highlights from 200 years of decorative arts under the Romanovs include three cigarette cases, a chamber stick, a cigar box, and a large diamond-studded leather portfolio by Fabergé. - April 16 – July 17, 2016 Palace Museum – Meridian Gate, Beijing, China

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts will be the first museum in the United States to exhibit works from its permanent collection when its world-renowned Fabergé collection travels to China. Press Release. - April 29 – October 2, 2016 South Karelia Museum in Lappeenranta, Finland

Imperial Gifts from Pavlovsk Palace

More than 150 items from the Pavlovsk State Museum collection in Russia are on display including objects from porcelain dinner services, cigarette cases and snuff boxes, fans, figurines, decorative articles and portraits, and items created by masters of the House of Fabergé. Catalog published when the venue was shown at the Turku Castle, Turku, Finland. - May 12 – September 25, 2016 Koldinghus Museum, Kolding, Denmark

Fabergé – Tsar’s Court Jeweler and the Connection to the Danish Royal Family

One hundred loans from members of the Danish royal family, who through family ties to the Russian emperor and his family, inherited these objects. They will be shown along with Fabergé from the King’s Collection at Amalienborg. Many of them have very rarely been on public view, since they are still used by the royal family. (Courtesy Royal Russia, Tuesday, December 22, 2015) - June 25 – October 16, 2016 Schloss Fasanerie, Eichenzell near Fulda, Germany

Fabergé – Gifts from the House of Romanov

The objects in the venue illustrate the connection of the Russian Imperial family to their German relatives through the children of Grand Duke Ludwig IV of Hesse and by the Rhine and his wife Alice, born a princess of Great Britain. The focus is not only on Fabergé, but also on the life stories of the givers and recipients. A catalog in German, Russian, and English will be published. - September 30, 2016 – January 6, 2017 Telfair Museums, Savannah, Georgia

The Tsars’ Cabinet: Two Hundred Years of Russian Decorative Arts under the Romanovs

Highlights from 200 years of decorative arts under the Romanovs include three cigarette cases, a chamber stick, a cigar box, and a large diamond-studded leather portfolio by Fabergé. - October 1, 2016 – April 16, 2017 The Russian Museum of Art, Minneapolis, Minnesota

Unknown Fabergé: New Finds and Re-Discoveries

Fifty to 75 Fabergé objects, many of them with Imperial provenances, will be displayed with archival photographs to present the object with its context, be it the personal story of its provenance, or its special role in the life of Russian society of that time. Catalog planned. - October 20, 2016 Re-opening of the permanent galleries for Pratt Collection, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond

The annual Winter catalog published by ALVR is available online, or in hard copy. Wartski 2015 highlights online.

Dr. Karen Kettering has joined John Atzbach Antiques, dealer of Fabergé and Russian art objects.

Postcard, Fabergé Silver-Gilt and Enamel Cigarette Case

Presented by Empress Alexandra Feodorovna to Nicholas II

on May 29, 1897, the Birth of Grand Duchess Tatiana,

Their Second Daughter.

(Courtesy McFerrin Collection)

Well-worn Silver-Gilt War Production Cigarette

Case with the Inscription War 1914-1915

(Wiki)

- With the addition of over 150 new pieces, the McFerrin loan exhibition now includes 500 jeweled treasures.

- The discovery of the original elephant surprise belonging to the 1892 Diamond Trellis Egg in the McFerrin Collection is discussed in the Egg section above.

- Highlights from the McFerrin Collection Fabergé objects have been published as postcards.

- Museum lecture: “A Collector’s Tale: The McFerrin Fabergé Collection” by Dorothy McFerrin, Monday, April 18 at 6:30 p.m.

- Film screening at the museum: “Fabergé: A Life of Its Own” followed by a Q&A with Dorothy McFerrin, Monday, April 25 at 6:30 p.m. Additional information about the film, Fabergé Research Newsletter, Spring 2014. This revised version includes the Third Imperial Egg found in 2014.

Richmond, Virginia

The Winter/Spring 2016 issue of the magazine, VMFA: Virginia Museum of Fine Arts announces the opening of re-designed, renovated, and expanded Fabergé and Russian Decorative Arts Galleries in October 2016. They will contain the Lillian Thomas Pratt Collection of five Fabergé Easter eggs in walk-around cases, and 300 other objects. The monumental Fabergé silver kovsh, a part of the Jerome and Rita Gans Collection of Silver, made out of 25 pounds of silver is illustrated in the feature story of this newsletter.

St. Petersburg, Russia

The 2015 International Fabergé Museum Conference: Lapidary Art was held October 8-10, 2015, in St. Petersburg, Russia. Attendees heard presentations on:

- Day 1 relating to:

Fabergé’s Lapidary Works: Unique Artistic Ideas and Perfect Execution

Lapidary Art in Russia in the 19th – 20th Centuries: Unknown Facts and Surprising Discoveries

Origins of Fabergé’s Lapidary Art: West and East - Day 2 relating to:

Russian Lapidary Art is Exhibited in the World’s Best Collections

Lapidary Art Restoration in Russia and Abroad

Modern Lapidary Art: Strong Ongoing Tradition and Innovation

A public lecture by Caroline de Guitaut, Senior Curator of Decorative Arts, Royal Collection Trust, London, entitled East Meets West: Russian Hardstones and the British Royal Collection brought “the house down” when Ms. Guitant announced the missing elephant surprise for the 1892 Diamond Trellis Egg held by the McFerrin Collection in Houston, Texas, had been found. Ms. De Guitaut’s lecture is recorded in English and in a simultaneous Russian translation. The elephant surprise of the Diamond Trellis appears at ca. 51 minutes into the video, and is discussed in more detail in the Eggs section of this newsletter.

On December 29, 2015, the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg opened the Carl Fabergé Memorial Rooms in the General Staff Building. Two permanent galleries are dedicated to the art of Carl Fabergé and his contemporary gold/silversmiths with a third gallery serving as a temporary exhibition space. At the present time the exhibit, Fabergé in the Great War, is on loan from the Russian National Museum in Moscow with 43 objects produced in copper and brass by the firm from 1914-1918. Fabergé’s Moscow Mechanical Factory produced grenades, cartridge-cases, percussion primers and time fuses, traveling samovars and kettles, saucepans, wash bowls, syringes and sterilizing pans. Fabergé informed the War Office that “for the duration of the war I have opened a mechanical factory which employs 600 people, engaged exclusively on work relating to the defence of the state, and at the present time the firm is completing the first order for 6,500,000 parts for hand grenades…” Unusual items included in the Russian National Museum collection are the bell that rang for the start and finish of the working day at the Moscow Mechanical Factory and the telephone from Carl Fabergé’s office at the firm’s headquarters at 24 Bolshaya Morskaya Ulitsa in St. Petersburg. (Information Courtesy Marina Lopato)

Showcased in the permanent galleries:

Alexander III 25th Wedding

Anniversary Clock

by Fabergé, 1891

(Courtesy Christie’s New York)

Miniature of the Russian State Regalia

by Fabergé, 1900

(© State Hermitage Museum)

Fabergé Rothschild Egg

Clock, Presented by

Beatrice Ephrussi de

Rothschild to Germaine

Halphen on the Occasion

of Her Engagement to

Beatrice’s Younger Brother,

Baron Edouard de

Rothschild, 1902

(© State Hermitage

Museum)

Additional information: Hermitage Museum | Royal Russia, Saturday, January 9, 2016

Cherdakly, Ulyanovsk Region of Russia

Vasilii Ivanovich Zuiev, Artist-miniaturist

of the Fabergé Firm by Vasilyeva,

N.I. and V.V. Skurlov, 2015

(Illustration Courtesy Valentin Skurlov)

Zuiev Miniature Portrait

(ca. 1.5 inches high)

of Tsesarevich Alexei, Painted

on Ivory on the 1911 15th

Anniversary Egg

(Courtesy Fabergé Museum,

St. Petersburg, Russia)

Additional information: Website in Russian

- Professor Hans Bjelkhagen and his colleagues published a detailed paper, Malcolm Forbes, Fabergé Eggs and Optoclones™ describing a new 3D imaging technique for the recording of ultra-realistic images as applied to Fabergé eggs – read about it yourself! A sample of two holograms was shown during the International Fabergé Museum Conference, St. Petersburg, Russia. (See Museum News above).

- The Fabergé Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia, during the 2015 Symposium unveiled another in the series of books listed in a previous Fabergé Research Newsletter, Winter 2014. Edited by Pomigaloff, A. and E. Lukyanov, Fabergé Museum in St. Petersburg (2015), the softbound book is lavishly illustrated featuring sections on Imperial Easter eggs, commemorative items from the Romanov family, Cabinet gifts, famous customers, etc. It ends with the history of the Shuvalov Palace where 4000 art objects owned by the Link of Times Collection (one-fourth of which are Fabergé) are displayed.

- Alexander von Solodkoff wrote an essay in German entitled, “Precious Gem Flowers: Maria Pavlovna and Flowers from Fabergé” for the book, Maria Pawlowna, Grossfürstin von Russland, Herzogin zu Mecklenburg-Schwerin, with the subtitle, Facets of a Life between Schwerin and St. Petersburg, published by the Friends of the Castle of Schwerin, 2015. It contains the re-discovered poem by Robert de Montesquiou (1855-1921) “Fleurs de Gemmes” which he wrote for the Grand Duchess, and was first published in the French newspaper Le Figaro on December 5, 1907, as a tribute to her amazing collection of Fabergé flowers.

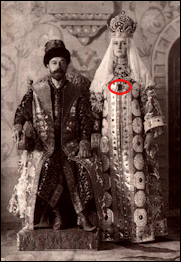

All the time that the jewels were being handled, a representative from Fabergé’s, the well-known jeweller, who nowadays takes charge of a large portion of the Imperial jewels, was present as an expert to note the jewels and see that none disappeared. Mme. Ivaschenko described her anxiety on account of the responsibility she felt as almost overpowering. However, she was rewarded by the thanks of the Empress, who was delighted with the results, and she was one of the very few who was afforded a place in one of the galleries to witness the procession.

It will occur to many people to ask how much such a costume as the Empress wore can have weighed. Well, the Empress carried no less than sixty pounds of costume, and, as you may imagine, anything but the most deliberate and majestic movements were out of the question.” (“The Czarina’s Jewels”, Sydney Evening News, Tuesday, June 9, 1903, p. 2)

Nicholas II and Alexandra

Feodorovna at the 1903 Boyar Ball

(wiki)

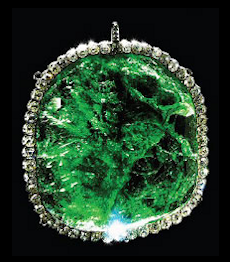

Emerald Pendant, 245 Carats

(Courtesy Diamond Fund, Kremlin)

Gold, Diamond and

Demantoid Bangle

(Courtesy

Christie’s Geneva)

Lilies of the Valley Basket

(Gray Collection and Metropolitan Museum of Art)