Fabergé Moscow excelled at producing large scale kovshes in the Russian taste using the lost-wax method: A plaster mold is created from a wax model which is melted away as heated silver is poured into the form. The technique limits the original wax model to individual use and therefore, the costs associated with such a commission could not be defrayed by creating a series which might benefit from the economies of scale. It is likely the bogatyr series discussed earlier were conceived individually and additional close study could reveal further insight into Fabergé’s production.

Bogatyr Kovsh and Detail Formerly in the Forbes Magazine Collection

(23 1/8 in. high/59 cm)

(Courtesy Forbes Magazine Collection)

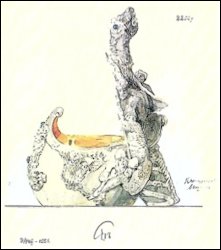

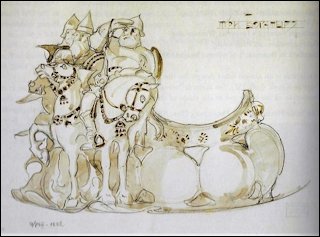

Pencil and Watercolor Drawing

for a Similar Kovsh

(von Habsburg and Lopato, Fabergé:

Imperial Jeweler, 1993, 415)

The Revyakin kovsh has been compared to a pencil and watercolor drawing now on display in the recently opened Carl Fabergé Memorial Rooms in the General Staff Building of the State Hermitage Museum. When the drawing was published in von Habsburg and Lopato’s Fabergé Imperial Jeweler (1993), p. 415, it was inscribed for 2,200 rubles and the Cyrillic inventory notation E/RO III-1591. In later publications, von Habsburg, Fabergé Craftsman and His World (2000), p. 121, and the recent Revyakin book (p. 92), the price notation does not appear.

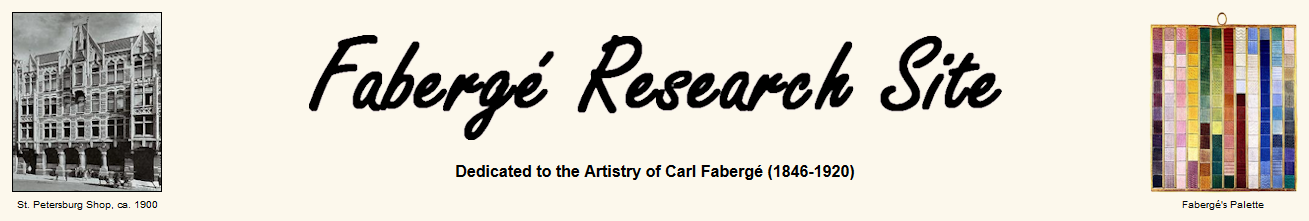

Decathlon Trophy for the

1912 Olympic Games in Stockholm

(47.5 x 59.8 x 31 cm/19 x 24 x 12 in.)

(Courtesy Olympic Museum,

Photograph © IOC/Jean-Jacques Strahm)

Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, Grandson of Alexander II and

Cousin of Emperor Nicholas II, and a Guard’s Officer was

Chosen to Ride for Russia in the 1912 Olympics

(Courtesy Royal Russia)

In anticipation of the 1912 Olympics, St. Petersburg jewelers were invited to compete for a trophy to be created in the form of a traditional Russian drinking vessel. Larissa Zavadskaya in her article, “Design Drawings of C. E. Bolin’s Items of Jewelry in The Hermitage” in Jewellery & Silver for Tsars, Queens and Others. W. A. Bolin 200 Years, 1996, 219-223, notes Bolin’s entry was turned down in favor of Fabergé’s which was approved for the Olympic kovsh. It appears various drawings preserved in the Hermitage Museum for kovshes and tankards decorated with epic heroes may relate to this competition.

It is certainly true the Imperial Cabinet purchased stock from Fabergé and other prominent makers in large quantities, particularly in preparation for extended official tours and lavish gifting abroad. However if, as has recently been stated in the Revyakin text (p.95), the Hermitage drawing now displayed in the General Staff Building was submitted for inspection to the office of His Imperial Majesty as the proposed Stockholm Olympic prize of 1912, then certain monumental kovshes were specially conceived for particular presentations.

The Olympic kovsh was reviewed once again to find links between the composition and the specific event for which it was created. The object features a prominent Bogatyr figure in chainmail, this time leaning forward against his shield as he surveys the horizon surrounded by his men. The sizeable handle enriched with scrolling motifs suggests swirling wind or surging seas surrounding a rudder. The totemic support for the principle figure is replaced by a clutch of oars and the prow features galloping horses. The iconography does not seem to relate to the events comprising the decathlon of various races, hurdles, jumping, shot put, javelin, discus and pole vaulting. None of these categories required the use of a boat or equestrian elements depicted in the prize’s sculptural relief.

Undeterred, a search began to see if the inventory number scratched into the kovsh could be traced and whether the Olympic museum in Lausanne could shed any further light on this piece. The kovsh presented to the winner of the 1912 Stockholm decathlon has a Moscow hallmark with the years 1908-1917. It is known the piece was in existence in time for the 1912 Olympics and the scratched inventory number 18831 cross references with Imperial Cabinet documentation from 1911. Dr. Valentin Skurlov, independent researcher, has generously shared information from archival documents which shed light on the timeline relating to the Olympic kovsh:

- On April 6, 1911, the General Staff Headquarters in St. Petersburg acknowledged correspondence from Count von Rosen (a prominent Swedish sportsman and campaigner for equestrian events), and the agreement of the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs to allow Russian officers to participate in the 1912 Olympic Games.

The agreement to permit officers to be seconded to the games would have been important for Russia as it, in effect, permitted some of the Empire’s most elite horsemen and highly trained athletes to participate. It is interesting to note that Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich of Russia, grandson of Alexander II and cousin to Nicholas II, was a guard’s officer chosen to ride for Russia in the 1912 Olympics. Certainly there were other noblemen highly trained in various disciplines who could qualify as amateur sportsmen whilst benefiting from a lifetime of preparation for such a competition.

- On May 4,1911, the Russian office responsible for administering the Imperial Household (Ministry of the Imperial Household Office) reported Baron de Coubertin inquired, on behalf of the Prince of Sweden, as to His Imperial Majesty’s intentions to grant a challenge cup. The Ministry of the Imperial Court submitted the choice of award to Nicholas II for approval.

- On June 9th, the Imperial Cabinet documented that it pleased the Emperor to choose a kovsh formed as a boat with the State coat of arms and warrior figures, stock number 533 for 2,500 rubles.

Recalling the Hermitage drawing originally marked for 2,200 rubles, the discrepancy with the figure noted by the Imperial Cabinet of 2,500 rubles throws further doubt on the drawing being the approved design for the Olympic kovsh. This does not preclude that the kovsh was a special commission, only at this time the object’s full background is not known. We may not understand the Fabergé process from conception to delivery of the Revyakin or Olympic kovshes, but recent publication and archival revelations certainly contribute to our understanding of the Fabergé era.

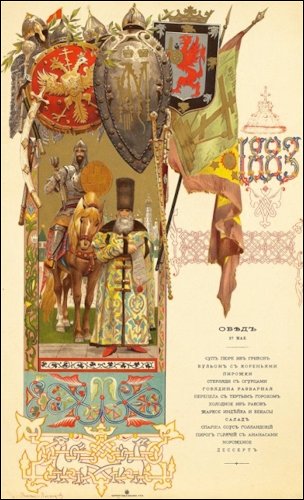

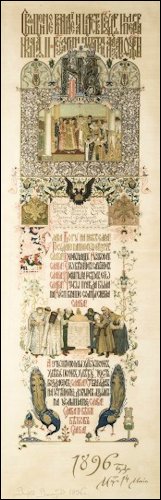

Alexander III, while still Tsesarevich, visited Paris with his father and there encountered the works of Russian artist, Viktor Vasnetsov (1848-1926). Alexander insisted on purchasing Vasnetsov’s Acrobats for his personal collection. At the 1882 Moscow Pan-Russian Exhibition, Carl Fabergé was awarded the gold medal and St. Stanislas for his replica of a 4th century gold Scythian bangle, and in 1885 was named ‘Supplier to the Court’ by then Emperor Alexander III. The works of the two artists – Vasnetsov and Fabergé – were to converge in the ‘Russification’ of Alexander’s focus on the Decorative Arts. Vasnetsov was chosen to produce the art for Alexander’s 1883 Coronation Menu, featuring the bogatyr theme. The artist alludes to the subject of his future monumental work with the positioning of the three distinctive warrior helmets at the top of the menu. This menu commission continued in 1896 at the ‘Tsar’s Repast’ following the coronation of Nicholas II where, at each place setting lay a rolled copy of the painted menu created by Vasnetsov, tied with a tasseled, golden chord.

1883 Coronation Dinner Menu for Emperor Alexander III

by Viktor Vasnetsov

(Courtesy Pinterest)

1896 Coronation Dinner Menu

for Emperor Nicholas II

by Viktor Vasnetsov

(Courtesy Shapiro Auctions)

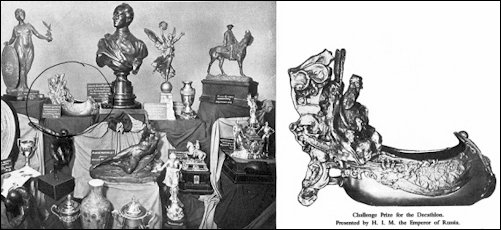

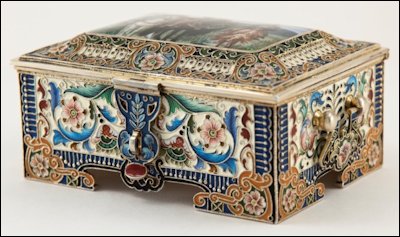

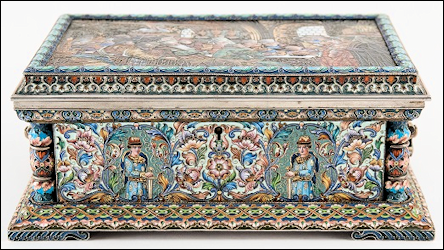

This essay offered me an opportunity to study in detail a silver-gilt box, a personal favorite of Artie McFerrin, from the larger McFerrin Collection on view at the Houston Museum of Natural Science. Mr. McFerrin expresses his love for Rückert boxes: “They are true history, telling a story or folklore of Russia passed down through culture and art.” He further appreciates these images represent culture and historical events through the eyes of the painters.

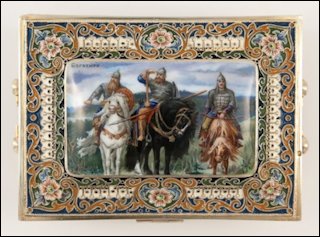

The detailed description of the McFerrin piece reads: Russian silver-gilt box, shaded cloisonné and en plein enamel casket, made by Feodor Rückert (a supplier to Fabergé), Moscow ca. 1896-1908 with scratched inventory number 20409. Rectangular, the hinged cover centering an en plein enamel plaque depicting three of the most famous bogatyrs, Dobrynya Nikitich, Ilya Muromets, and Alyosha Popovich, as in Viktor Vasnetsov’s 1898 painting Three Bogatyrs. Enameled overall with floral and scrolling motifs on cream white ground, the interior of the lid with blue translucent counter enamel, gilt interior, dimensions 2 x 4 1/2 x 3 1/8 inches.

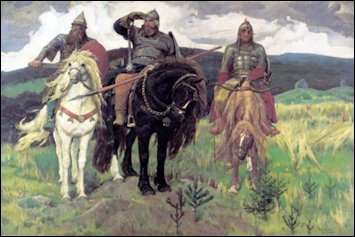

Vasnetsov’s children recalled that The Bogatyrs painting followed them from city to city, from apartment to apartment. Sketched images of his vision were first put to paper in 1871. Thus, the gargantuan 9.7 x 14.6 feet (295.5 x 446 centimeter) composition was begun in the reign of Emperor Alexander II, developed during the reign of Alexander III, and was at last hung in 1898 at the Tretyakov State Gallery, Moscow during the reign of Emperor Nicholas II. Vasnetsov labored through the reigns of three emperors to bring his canvas Three Bogatyrs to fulfillment.

Russian Silver-gilt Box by Feodor Rückert

(Courtesy McFerrin Collection)

The Three Bogatyrs by Viktor Vasnetsov

(Courtesy Tretyakov State Gallery, Moscow)

Silver Kovsh Design in the Old Russian Style with Figures of

‘Three Warriors’ Stamped Fabergé

(Courtesy Hermitage Museum)

The Three Bogatyrs are named: Dobrynya Nikitich, Ilya Muromets, and Alyosha Popovich. Some illumination of them as individuals brings further appreciation of the box and its stylistic and historically encoded message. Russian researchers concluded Vasnetsov’s Three Bogatyrs were actual historical personalities. They emerged as valiant ‘Defenders of the Russian Lands’ against the Varyags (Vikings), Pechenegs (Turkic tribes of the Central Asian steppes), and Polovtsians (Cumans – tribes from North of the Black Sea & along the Volga).

In Vasnetsov’s painting, Dobrinya Nikitich is on the left: His expression is alert, his shield is up, his sword is being drawn; he is battle-wise and born to conquer. Even the head of his billowing white steed is raised in challenge, with nostrils flared into the winds of any oncoming siege by natural phenomenon or human malice. Who is this ancient warrior who, while not occupying the commanding position in the painting, nevertheless is the catalyst to victory? Perusal of facts and allusions set forth by the researcher/writer in the USSR article “The Bogayrs”1 reveal fascinating substantiation as to this pivotal Hero, as the uncle of Vladimir, and so stood closest to the ‘Throne of Russia’.

Iliya Murometz dominates the central position in Vasnetsov’s masterpiece. His powerful presence bulges from the canvas. Shading his eyes, he surveys the vast Russian horizon for insurgents, his felt-booted foot confidently withdrawn from the stirrup iron. Aliosha, to his left, stares almost blankly, a bow resting on this horse’s lowered neck. All await the incontestable order and edict of Murometz, this hero who performed his feats at the court of Vladimir I, ‘The Red Sun’. The epithet accurately translates as ‘The Fair’ from the ‘red’ (krasnye). Deemed by the bylina to be the ‘oldest and wisest of the Bogatyrs, folklore reveals Iliya as a crestfallen man who spent his first 33 years of life as a cripple, without the use of his legs. The fabled invalid is said to have been miraculously cured by the appearance of two holy pilgrims. The holy men happened by his humble house asking for water to quench their thirst. He responded to their request with regret, explaining that he was unable to walk. The holy men commanded Iliya to arise and as he did, he felt a great strength surge through his body. Now energized with heroic vigor, he set off for Kiev to serve the reigning Duke, Vladimir. Scholars have found the name ‘Iliya Murometz’ in historical documents and associated historic sites. In the 16th century, the German emperor sent his diplomat Erikh Lyasota on a mission to the Zaporozhian Cossacks. En route, Lyasota passed through Kiev and was shown the famous Cathedral of Sophia Kievskaya. It was in this cathedral he saw a Bogatyr side-chapel containing the tomb of Iliya Murometz.

Aliosha Popovich sits astride his chestnut charger on the far right. While the artist was visiting his patron, Savva Mamontov’s artist’s retreat at Abramtsevo, he found models in his host’s son, as well as in a local chestnut horse, Fox. Given the epithet, ‘The Parson’s Son’ by some sources, this young knight, nonetheless, is said to have persuaded the wife of the third Bogatyr, Dobrinya, to marry him in the wake of the latter’s six-year absence. In true fable form (recalling the long delayed return of Odysseus to Penelope), Dobrinya then reappears at the wedding disguised as a minstrel, to reclaim his wife. Tradition alleges Aliosha won his battles through youthful cunning and courage, and legend aptly heralds him as a lyrical romanticist.

Vasnetsov’s symbolic depiction of these Legendary Heroes from Russia’s foundations joined similar themes by such artists as Ivan Bilibin to popularize the myth and folktale preserved in the Russian/Primary Chronicles or Tale of Bygone Years. This often referenced source is a history of Kievan Rus from about 850 to 1110, originally accumulated in Kiev about 1113. The work is considered to be a fundamental source in the interpretation of the history of the Eastern Slavs compiled by one Nestor the Chronicler.

On the Fabergé sketch, it is a clean-shaven Aliosha Popovich on the far left, with his helmet echoing that in the painting, and just a faint bronze shadowing of his chestnut horse. The center position in the drawing is held by Dobrynya Nikitich and once again his helmet distinctly corresponds with the painting, along with the detail of his shaggy beard, shield decoration, and detail on his horse’s breastplate. And finally, we have the greatest bogatyr of all, Ilya Muromets who, though now on the right of his comrades in arms, still dominates the drawing. The pose of both the warrior and his charger mirror the original canvas: the helmet, gloved hand shading his eyes, mace strap over his gauntlet, felt boot pulled out of the stirrup iron, and his shield slung over his left shoulder. His steed, flexes his neck to his left, detail of the bridle and breast plate are consistent, and the heavy ‘feather’ on the horse’s fetlocks (ankles) is carried out in the drawing as well. One wonders if the piece was ever made, and if so it survives. Contact author: DeeAnn Hoff

Folktales, by their very nature, are embedded with myth and symbol and proved a stimulating Muse for the artist. With reference to Vasnetsov’s work on the alluring Fabergé box in this discussion, allow me to conclude with an applicable reference to the Russian Folktale of Vasalisa: In the course of accomplishing the series of tasks set forth by Baba Yaga, Vasalisa asks the Grandmother about three horsemen she sees. Baba Yaga explains the white horse is her Day, the red horse is her Rising Sun, and the black horse is her Night. In myth and folklore, these are the ancient colors connoting birth, life, and death.

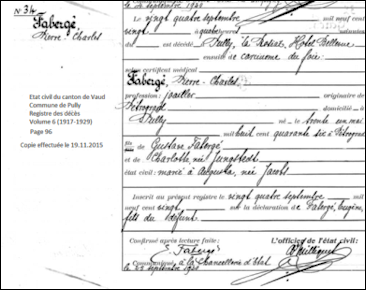

Fabergé‘s retreat from Russia in 1918 was depressing and ultimately exhausting. Travelling from Riga to Berlin after the Bolsheviks attack, the third consecutive city he went to was Frankfurt-am-Main, then Homburg and Wiesbaden where he spent his 74th birthday with friends. It was there depression and physical exhaustion caught up with him and he fell ill. His wife Augusta brought Carl and their son Eugène to Lausanne where she was already established.

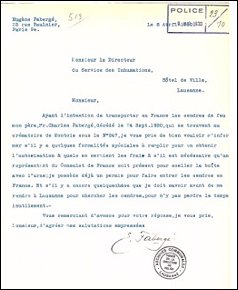

Five years later in 1925 his wife Augusta died at Cannes in France and understandably the family was keen to unite the remains of their parents. Eugène Fabergé successfully applied to the authorities in Lausanne to allow an exhumation and it was granted not just for the ashes but the cinerary urn and its box. This information comes from Eugene Fabergé’s request to the “Service des Inhumations de Lausanne”.

Death Certificate of Carl Fabergé

Exhumation Requests to the City of Lausanne, Switzerland

(Source: Archives cantonales vaudoises N/Ref.: GJe/gje/cb/2015/1461 et 1046)

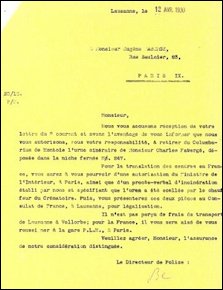

Fabergé Tombstone in Cannes, France

(Wiki)

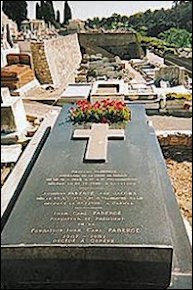

Carl Fabergé in Wheelchair with His Wife Auguste Fabergé (far right), Wiesbaden, 1918

(von Habsburg, Géza. Fabergé, 1986, 30)

Henry C. Bainbridge mentions in his 1949 biography, Peter Carl Fabergé: Goldsmith and Jeweller to the Russian Imperial Court and the Principal Crowned Heads of Europe, the jeweler celebrated his 74th birthday on May 30, 1920, with ‘15 of his old Petersburg friends’.

I found documents in Wiesbaden, which prove Fabergé celebrated this birthday in “Hotel Imperial” in Wiesbaden, Sonnenberger Street Nr. 16 /Corner Leberberg, while seeking a cure in the spas. In the guest-lists of the “World-Spa-Town Wiesbaden”, dated May 29 – June 2, 1920, individuals are listed who arrived on this weekend in Wiesbaden to visit the aging and already ill Carl Fabergé. His wife Augusta came from Lausanne, one of his sons, mentioned as “Mr. Fabergé from Petersburg” (probably Eugène or Agathon) and others from Russia are on the list. Géza von Habsburg published a photo of Fabergé sitting in a wheelchair on a terrace in front of a house after his arrival in 1918 as an emigré in Wiesbaden. An article about my findings was published in the Wiesbadener Kurier, May 28, 2016, 25.

In October 2016, I will be attending the Fabergé Symposium in St. Petersburg to learn more him, and it is my hope to have a Fabergé exhibition in the Wiesbadener “Kurhaus”, perhaps 2018 (100 years after end of World War I) or in 2020 (100 years after Fabergé’s death).

Fersman Portfolio and Imperial Crown (Plate II), Imperial Globe with

Great Sapphire and the Indian Solitaire (Plate VII), Fragment of the

Great Imperial Chain of St. Andrews Order Plate IX.

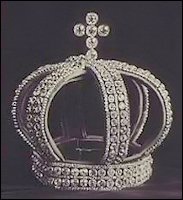

Nuptial Crown 1922 Photograph for the Fersman Portfolio, On View

at Hillwood Estate, Museum and Gardens, Washington, DC.

(Courtesy Christie’s)

FRN, Fall 2010 Wintraecken and McCanless introduced their research with this headline Fersman Portfolio – Fabergé Jewels – Nuptial Crown and these words:

FRN, Spring 2012 Second in-depth article, Fersman Portfolio – Fabergé Jewels Reviewed by the original authors.

Later that year, the authors were contacted by Jenna Nolt, librarian at the Unites States Geological Survey (USGS in Reston, Virginia), about the discovery of an album with a hand-designed cover containing photographs relating to the Fersman Portfolio. A press release and a public radio story on the newly-discovered album entitled Russian Diamond Fund (dated 1922) with additional links about the discovery tell the story. FRN, Spring 2013.

FRN, Readers Forum, Winter 2015 Will Lowes from Australia and Erik Schoonhoven from the Netherlands touched on the topic again.

August 1, 2016 Rose Tozer in her email advises the GIA Library has now available a digital copy of the Fersman Portfolio in English. The library houses perhaps the world’s most comprehensive collection documenting the history, science, business, and art of gems and jewelry. This online collection from the Richard T. Liddicoat Gemological Library and Information Center presents some of the most unique and rare books in the library’s collection. GIA is a nonprofit institute dedicated to research and education in gemology and jewelry arts.

But the story continues with an additional discovery through the vigilance of astute readers. This time it relates to the Nuptial Crown mentioned in the first paragraph of this review. The crown made in 1848 worn by many Russian Imperial brides, is shown in the Fersman Portfolio as Plate XXVI, sold in London at Christie’s, March 16, 1927, Lot 62 for £6,100 and is today a proud possession of the Hillwood Museum in Washington (DC). FRN, Fall 2010 details the history of the crown.

The collage of the Imperial Russian crown worn by Romanov brides from 1866-1908 is amended thanks to the detective work of Dr. Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm, scholar and author (Finland) and Timothy Adams, independent researcher (USA).

1866

Tsarevna Marie

Feodorovna

1874

GD Maria

Alexandrovna

1884

GD Elisabeth

Feodorovna

1884

GD Elizaveta

Mavrikievna

07/1894

GD Xenia

Alexandrovna

11/1894

Alexandra

Feodorovna

1902

GD Elena

Vladimirovna

1908

GD Maria

Pavlovna

‘Miss Universe 1952’ Wearing the Nuptial Crown

(Wiki)

A photo from a Cartier advertisement for 1953.

The model is wearing the Russian imperial

nupital crown which was owned by Cartier

at the time.

At press time, two new links were shared by Annemiek Wintraecken from the Netherlands, who has been fascinated with this tiara over the years. The Miss Universe Crown, Through the Years, and a Cartier advertisement.

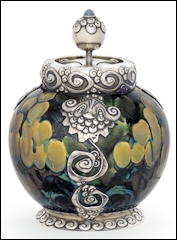

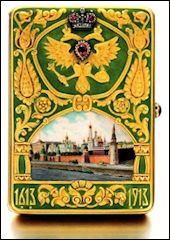

Fabergé Tobacco Humidor with

Ceramic Body by the Imperial

Stroganov School Sold for $193,008

(Courtesy Christie’s London)

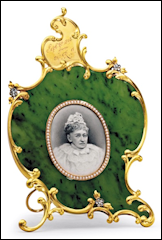

Joan Rivers Sale: Fabergé

Nephrite Photograph Frame

Presented by Queen Victoria to

Queen Louise of Denmark,

$245,000. Video with

Melissa Rivers

(Courtesy Christie’s New York)

Research Discovery by Darin

Bloomquist for a Fabergé

Romanov Tercentenary

Cigarette Case

(Courtesy Sotheby’s London)

Fabergé Nephrite and Silver Cane Handle

on an Advertising Postcard

The Newsletter Editor’s Favorite!

(Courtesy Sotheby’s London)

Fabergé Nephrite Photograph Frame Discovered

at Valuation Day, ca. $24,000

(Courtesy Catherine Southon Auctioneers & Valuers Ltd)

November 4, 2016 Coutau-Bégarie Art Russe: Collection du – Prince et and Princessesse Felix Youssoupoff (Courtesy Royal Russia)

Russian Week in London:

- November 28, 2016 Christie’s London Russian Art

- November 29, 2016 Sotheby’s London Russian Works of Art

- November 30, 2016 MacDougall’s London Russian Art, Works of Art, Fabergé and Icons

(Updates are posted in Exhibitions on the Fabergé Research Site)

Hardstone Animals

(Courtesy Museum Schloss Fasanerie)

Fabergé Sedan Chair by Mikhail Perkhin

(Private Collection, Courtesy The Museum

of Russian of Art, USA)

Fabergé, Geschenke der Zarenfamilie (Fabergé Gifts from the Tsar’s Family)

Exhibition contains 119 Russian and Fabergé items, mainly personal gifts from the last two Russian emperors and empresses, or Grand Duchess Elisabeth (Ella) to their relatives in Germany, the princely family of Hesse-Darmstadt. All Fabergé objects and some by competitors like W.A. Bolin or Sumin are illustrated in a catalog (in German, Russian and English), which includes descriptions and recently-discovered invoices from the Imperial Cabinet. (Information Courtesy Alexander von Solodkoff)

October 6-8, 2016 Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia, is hosting an International Academic Conference Dedicated to the 170th Anniversary of the Birth of Carl Fabergé. The Vekselberg Collection encompassing 1000 objects is on view in the beautifully restored Shuvalov Palace.

New Dates! October 8, 2016 – February 26, 2017 The Museum of Russian Art, Minneapolis, Minnesota

Unknown Fabergé: New Finds and Rediscoveries

More than 50 Fabergé objects, many of them with Imperial provenances, will be displayed in the context of their personal story or role in the life of society at that time. An exhibition catalog is to be published. Mark Moehrke, Project Consultant and Editor, and Marilyn Sweezey, Guest Curator.

October 22, 2016 The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts’ renowned Fabergé collection is returning from an international tour, and will be displayed in a new suite of renovated galleries featuring 280 objects – composed of Fabergé and other Russian decorative arts – in a multi-layered interactive experience. VMFA will be the only American art museum with five galleries dedicated to Fabergé and other Russian objects.

Extended! Closing on October 29, 2016 Fabergé in the Great War shown as a temporary venue in the Fabergé Rooms of the General Staff Building, Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia.

November 3-4, 2016 Symposium entitled The Wonder of Fabergé: A Study of the McFerrin Collection will be held at the Houston Museum of Natural Science, Texas. Fabergé enthusiasts are invited to attend!

November 13, 2016 Wilfried Zeisler, Curator of Russian and 19th century Art at Hillwood Estate, Museum and Gardens, Washington (DC) presents a talk, Fabergé: The Path of a Brilliant Jeweler, at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, in Richmond.

Extended after its previously announced closing on November 27, 2016! The Matilda Geddings Gray Collection of Fabergé on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art due to its outstanding attendance records has been extended indefinitely. Wolfram Koeppe, Marina Kellen French Curator European Sculpture and Decorative Arts, at the Metropolitan writes, “Fabergé enthusiasts all over America are very pleased to see this collection in New York since it is the only substantial exhibition of Fabergé’s splendid work on the East Coast …”

October 2017 Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland

Fabergé and the Russian Craft Tradition (working title)

Objects collected by Henry Walters (1848-1931), art collector and founder of the museum, gifts from the Jean M. Ridell Collection, and a necklace from a private collection will be showcased. The 1901 Gatchina Palace and the 1907 Rose Trellis eggs by Fabergé will be shown. A scholarly catalog is planned.

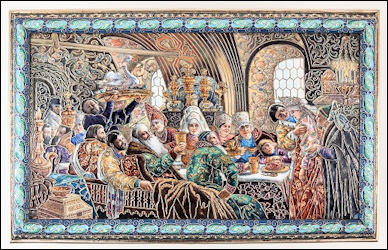

(A) Enameled En Plein Image on a Feodor Rückert Casket of The Boyar Wedding Feast by Konstantin Makovsky

(Courtesy McFerrin Collection)

The coronation of Emperor Alexander III in 1883 resulted in renewed engagement with Russia’s national history including a fascination with the settings, characters, and customs of the boyars, the Russian elite of the 1600s. Because so much was known about boyar wedding traditions, Konstantin Makovsky (1839-1915) chose to focus on this aspect of boyar life for his masterpiece. The Boyar Wedding Feast was originally staged as a tableau vivant in which the feast was staged live for an audience in the Makovsky home. The artist later recorded this event on canvas. The painting highlights a pivotal moment in the feast when the stuffed swan – symbol of beauty and fertility – is presented to the wedding couple shortly before they leave to consummate the marriage. An older male guest is shown toasting the bride and groom. In Russian tradition, he declares the wine has turned bitter asking them to kiss to make it sweet again. One sees a very reluctant young bride. She and the groom may never have seen each other before the betrothal because marriage in the 1600s was about economics and politics, not love. A matchmaker is pushing the bride forward to accept the kiss. The scene is rich with embroidered costumes, an array of authentic boyar antiques and the faces of some of Makovsky’s friends, relatives, and clients.

Because the artist not only studied wedding traditions, but also collected clothing and decorative objects from the period it gives the viewer an insight into how the Russian aristocracy dressed and lived prior to the time of Peter the Great and his Westernization efforts. The art and cultural history of Russia in the 19th century is also reflected in Makovsky’s other work. It was a period when artists looked back to Russia’s past for inspiration for their work. In the Boyar Wedding Feast one sees much more than the physical world and appearance of the boyars. One is given insight into their lives. For example, the expression on the bride’s face and her posture tell about her reluctance to go through with the kiss and maybe even the marriage. Such depictions caused one Makovsky scholar to conclude that his works “reveal themselves to be works of historical scholarship as much as of remarkable artistic imagination.” (Martin, Russell E., “The Artist as Historian: Makovsky’s Historical Sources and Artistic Message” in Zeisler, Wilfried, et al. Konstantin Makovsky, The Tsar’s Painter in America and Paris, p. 73)

Dr. Zeisler states, “Though less widely recognized today, the work of Konstantin Makovsky had tremendous influence on the art and culture of his time.” In Russia many objects were made depicting the painting and/or partial details from it. The casket in the McFerrin Collection, which we had the unbelievable privilege of admiring up-close without the confines of a museum display case, is an incredible example of craftsmanship from the Rückert studio. The Marjorie Merriweather Post Collection at Hillwood has other important examples of this style, i.e., a kovsh (C.) with a painted enamel miniature by Rückert depicting the bride and groom from the wedding.

The Boyar Wedding Feast never entered a Russian collection. Attempts to sell the painting in St. Petersburg, Paris and London were unsuccessful. After the oil painting won the Medal of Honor at the Antwerp Universal Exhibition in 1885 it was purchased by Charles Schumann, an American who owned a jewelry store in New York City and induced Makovsky to come to America where eventually he and his painting became famous.

Dr. Zeisler will be one of the presenters at the Fabergé Symposium in Houston, Texas, on November 3-4, 2016, discussing in more detail art objects of this genre in his talk, “From Canvas to Silver: Enameled and Repoussé ‘Paintings’ in Russian Jewelry at the Turn of the 20th Century”.

A catalog published for the Hillwood exhibition, Zeisler, Wilfried, et al. Konstantin Makovsky: The Tsar’s Painter in America and Paris is available in the museum shop and for autographing at the McFerrin Fabergé symposium in Houston, Texas.

Alex Nyerges, Director of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Presenting His Opening Remarks at the

Opening of the Fabergé Revealed Exhibition in the Forbidden City, Beijing, China

Barry Shifman’s Interview by Chinese Television Stations

(Photographs Courtesy of the Author)

In April 2016, a group of representatives from the (VMFA), including Director Alex Nyerges, Deputy Director for Art and Education and Chief Curator Dr. Michael Taylor, and I attended the opening of the exhibition Fabergé Revealed at the Palace Museum. We were thrilled to be witnesses to this historic occasion since the Beijing event signaled the first time a U.S. exhibition was displayed at the Palace Museum after a culmination of a seven-year partnership between the two museums. The Palace Museum shared its own treasures at VMFA during the Forbidden City: Imperial Treasures from the Palace Museum exhibition in 2014.

The official opening of the Fabergé exhibition in Beijing began with a visit to the Garden of the Palace of Established Happiness within the Forbidden City. It was my privilege to lead a tour of the exhibition after the ribbon-cutting ceremony. The Fabergé collection was beautifully displayed in the exhibit hall also in the Forbidden City, and we were thrilled to see our Fabergé objects on view in China. Three major TV stations aired stories about the venue. In the afternoon, the VMFA Member Travel group, which was touring China at the time, met with the VMFA and Chinese representatives, and then visited the Hall of Clocks and Watches, which houses a collection of Qing Dynasty timepieces, the Emperor Dowagers’ residential area of the Hall of Longevity and Wellness, and the Garden of the Palace of Compassion and Tranquility. A catalogue in Chinese of the Fabergé exhibition was produced by the Palace Museum.

The staff and docents at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts are eager to share our new and exciting exhibit beginning on October 22, 2016, with visitors to our museum.

Bequeathed to the museum upon her death in 1947, Pratt’s Fabergé collection consistently remains one of the highlights of the museum’s permanent collection. Pratt purchased most of her Fabergé objects from the Schaffer Collection and the Hammer Galleries, both of New York City, in the 1930s and 1940s. Comprised of correspondence, invoices, price tags, and detailed item descriptions, the archive illuminates Pratt’s mind as a collector, as well as her close relationship with the dealer Alexander Schaffer.

In all, 729 items have been digitized, resulting in about 1,500 new image files, all of which will be made available to the public via the museum’s website. The new online portal will launch on October 22, 2016, to coincide with the opening of the impressive new installation of Fabergé and Russian decorative arts in VMFA’s renovated permanent gallery.

In addition, the VMFA has also digitized a recently acquired coronation album documenting the coronation of Tsar Alexander III and Empress Maria Feodorovna in 1883. Only seven albums were commissioned by the Russian tsars to document and promote the pomp and pageantry of their imperial coronations. VMFA’s copy is in French, as it was created for a French dignitary attending the coronation. It is beautifully illustrated with almost 30 chromo-lithograph plates and resides in the rare book collection. The digitized album will be available to the public via the museum’s website in late October.

By the late 1920s, the world had changed, and a Russian émigré antique dealer in Paris, Alexander Alexandrovich Polovtsov (1867-1944), reignited Walters’ passion for Russian works of art. With Polovstov’s guidance, Russian art treasures found a safe repository in America. Henry acquired more than 70 pieces through Polovstov, including two prized Fabergé Imperial Eggs: the 1901 Gatchina Palace and the 1907 Rose Trellis. Walters also acquired antique icons and enamels, fine porcelain, and historic silver drinking cups. These works embody 800 years of Russian form, style, and character. Influences from Byzantium, the Islamic world, and Western Europe can be detected and speak to Russia’s complex history and rich cultural heritage.

1901 Gatchina

Palace Egg

Casket in the Form of an Izba,

a Traditional Russian Country Dwelling

by Pavel Ovchinnikov, Moscow, 1876

(Courtesy Walters Art Museum,

Baltimore, Maryland)

- The Irony of Fabergé Eggs: Mourning Jewelry for Alexander III

- Hidden Histories: Fabergé Silversmith Julius Rappoport

- Hidden Histories: Fabergé Objects of Rothschild Provenance

Christie’s London auction house published a promotional booklet, Russian Art featuring sale highlights over the years, including a large number of Fabergé objects. In English and Russian.

English publications from the Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia:

Fabergé Museum Publications in 2015, 2014 and reprinted in 2016

The Link of Times Historical and Cultural Foundation published Fabergé Museum in St. Petersburg, 2015. A general introduction to the museum’s contents includes the historical background to the collection, and stunning photographs of the various categories – Imperial Easter eggs, commemorative items from the Romanov family and the Cabinet gifts, famous customers, Russian enamel and silver, and a tour of the various exhibition rooms of the Shuvalov Place in St. Petersburg. Copies of this publication (above left) are available for purchase from the Museum Shop at the Hillwood Museum in Washington (DC).

Muntyan, Tatyana, with V.S. Voronchenko, general editor, Fabergé Masterpieces from the Collection of the Link of Times Collection (2014 and reprinted in 2016 with a new cover, above middle and right) The history for each of the Fabergé eggs in the collection is presented in detail.

Koldinghus Museum in a

Restored 13th Century

Medieval Castle

(Photograph Christel McCanless)

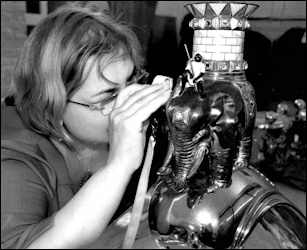

Tatiana Muntian, Exhibition Catalog Contributor, Examining the 1892 Presentation Kovsh

(Fabergé – Tsar’s Court Jeweler and His Association to the Danish Royal Family, 2016, pp. 12, 92)

Muntian, Tatiana. Feodor Rückert and Carl Fabergé (2016) published in Moscow. The lavishly illustrated tome presents in 702 pages the Maxim Revyakin Collection in Moscow. Text in Russian and English.

NEW! Available at the Houston Fabergé Symposium, The McFerrin Collection, The Opulence Continues by Dorothy McFerrin. Catalog of 300 new objects added to the McFerrin Collection since the publication of the previous book about the collection, From a Snowflake to an Iceberg: The McFerrin Collection in 2013.

Mieks Fabergé Eggs website hosted by Annemiek Wintraecken has an updated listing of YouTube egg videos organized by museums, old black and white Pathé and British Movietone newsreels, and documentaries.

YouTube Fabergé lectures at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts during the 2014 Virginia Museum of Fine Arts loan exhibition:

- Barry Shifman, Sydney and Frances Lewis Family Curator of Decorative Arts 1890 to the Present, Fabergé and the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

- Géza von Habsburg, Indepedent Scholar and Author

– Fabergé: Imperial Jeweller

– Fauxbergés: The Master Forgers Excellent visual introduction by the scholar who coined the word “Fauxbergé”.

Russian Language Publications:

Franz Birbaum, Fabergé’s

Chief Designer (2016)

Crimea and Fabergé

(2016)

Publication continues the series, Life of Remarkable Jewelers begun in 2011 with the first book, Mikhail Perkhin, Chief Workmaster of Fabergé. Birbaum (1872-1947), born in Switzerland, arrived in St. Petersburg at age 14, and eventually worked as an chief designer for the Fabergé firm from 1893 to 1918. Most of the 50 Imperial Easter eggs passed through his hands. Book highlights include almost all known publications about Birbaum, 12 letters from the archives of Tatiana Fabergé written between 1922-1939 by Birbaum and Carl Fabergé’s first son, Eugène, three articles by Birbaum devoted to art history published in Russian magazines 100 years ago, etc. In the words of the authors, the documents characterize Birbaum “as a miniature painter (as he named himself), master – enameller, technologist, gemologist, art historian, organizer of production and public man …” The monograph includes a chapter suggesting a missing Fabergé egg has been found. The debate continues among Fabergé scholars, if the egg in question is indeed the lost 1902 Empire Nephrite Egg. In Russian.

Fabergé, Tatiana, Skurlov, Valentin, et al. Crimea and Fabergé (2016).

Profusely illustrated booklet with well-known Fabergé objects combined with photographs of the original owners presented in a variety of topics, for example, “Romanovs and the Crimea, Products of Fabergé, 1914-1917”, pp. 22-23. In Russian.

The redesigned website of the London Fabergé dealer Wartski includes the text of an article by Geoffrey Munn, Fabergé and Japan (Antique Collector, January 1987, 37-45). It discusses the significant influence of Japanese works of art on the animal studies created by Carl Fabergé, an avid collector of Japanese netsuke.

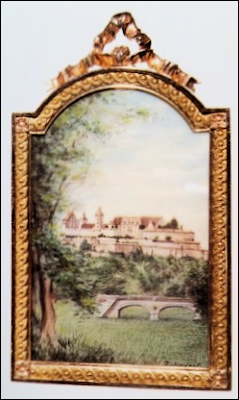

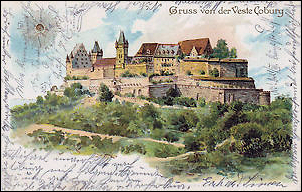

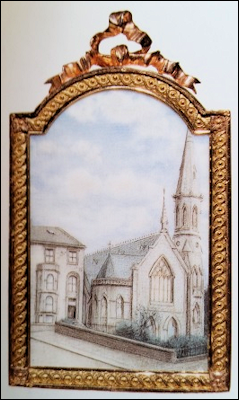

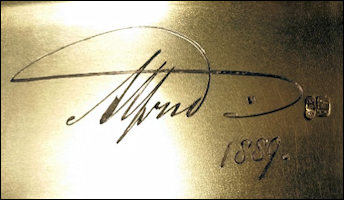

Painted Ivory Miniatures (1 x 11/16″, 2.5 x 2.8cm) by Zehngraf. Veste Coburg (left), Palace Church (right), Location Unknown (Courtesy Virginia Museum of Fine Arts)

Middle: Postcard of the Fortress Coburg (Private Collection)

The egg in the Pratt Collection in Richmond, Virginia, has a miniature incorrectly identified as Altes Palais in Darmstadt (left). A postcard found by Dr. Miller identifies the miniature painted by Zehngraf on ivory as the Fortress Coburg (Veste Coburg). Miller expresses doubt about the proper identification of the Palace Church in Coburg (right), since a search in the cities of Coburg and Darmstadt yielded no results. Readers are asked to assist in identifying the church. Contact: Barry Shifman

Pendant Brooch with Portrait Diamond

Covering Mandylion Icon

(Papi, Stefano. Jewels of the Romanovs:

Family & Court, 2013, 306)

Collector of silver mounted claret jugs would like to know what function the hole toward the bottom of the handle serves? Contact: Thomas Feilenreiter

Reader is looking for a Fabergé cigarette case similar in design and with a push piece on the upper right matching a cigarette case by Gabriel Niukkanen presented to Lord Suffield in 1901. The case in question would have been presented with an inscription to Dr. J.M. Atkinson, 1904. Has the Atkinson case been at auction, or are its whereabouts known?

Lord Suffield cigarette case

(Christie’s New York,

October 17, 1996, Lot 39)

Cigarette Case with the Cyril (Karl) Albrecht Mark

(Private Collection)

Case is missing a tinder cord. Is there a source to purchase a tinder cord used in the 1899 time period? Contact: Timothy Adams