- a remuneration for service rendered by state servants in Russia, and

- in the case of foreign recipients, jeweled boxes were a demonstration of good relations between two nations.

In other words, the boxes (as one of the many award categories) were official symbols of meritorious service, or of good foreign relations.

The snuff boxes discussed in this text were state visit gifts during the reign of Alexander III (1881-1894), and Nicholas II (1894-1917), respectively. The RIAS text cited above lists the portrait boxes given during the reign of Nicholas II to Russian recipients (p. 168), and to foreign recipients as diplomatic gifts (pp. 171 and 174). Imperial Presentation boxes were never inscribed with a dedication as recipients of these boxes had the option to return their boxes to the Imperial Cabinet in exchange for cash. Because of that policy, many of these boxes were “recycled” and then presented again.

The monetary value of the Imperial award boxes varied greatly. A general rule was that the value in rubles of an imperial gift to a Russian state servant should not exceed the annual income of the recipient. The value of snuff boxes presented to foreigners was entirely dependent on the importance of the recipient or of the occasion for the presentation. The boxes shown below are examples of gifts which have been highly upgraded in value. Large brilliant cut diamonds from the stock of the Imperial Cabinet have been added to the boxes in order to make the gift worthy of its recipient and of the important occasion for which it was presented.

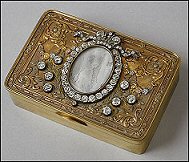

1889 Bismarck Box – Alexander III

Imperial Presentation Box

(Hodges Family Collection)

1894 Alexander III

Imperial Presentation Box

(Courtesy Musée National de la Marine)

1896 Alexandra Feodorovna

Imperial Presentation Box

(Courtesy Musée National de la Marine)

During the visit the Tsar had lengthy talks with Germany’s Reichs-Chancellor Prince Otto von Bismarck (1815-1898), who only five months later on 18 March 1890 at age 75, was dismissed by the German Emperor. Historians suggest the fame of the Iron Chancellor (as Bismarck was known) was too much for the new German sovereign. The date of the state gift was verified in the New York Times, October 15, 1889. The Alexander III miniature on the Bismarck box appears to match the portrait of the 1894 box (illustrated above in the middle) by Alexander Matveevich Wegner (Вегнер 1826-1894). An inscription added later to the box with the date of 1884, perhaps at the direction of a family member, pre-dates the actual date of presentation by five years.

Two snuff boxes on view at the Musée National de la Marine in Paris (Cadeaux des Tsars, May 28 – October 3, 2010) were both presented to the French Admiral Alfred Gervais (1837-1921). The box bearing the miniature portrait of Alexander III (middle) was a gift presented to him at the funeral of the Emperor. The admiral was present at both the funeral of Emperor Alexander III (November 19, 1894) and the wedding (November 26, 1894) of the young Imperial couple. The box on the right with the miniature portrait of Alexandra Feodorovna (unfortunately badly damaged) was presented to Admiral Gervais during Nicholas and Alexandra’s state visit to France in 1896. The admiral was attached to the Empress’s person during this visit. An important purpose of the visit was to reinforce the Franco-Russian alliance initiated by Alexander III. During the visit the young Tsar laid the cornerstone of the Alexander III Bridge in Paris, which to this day has remained a perceptible symbol of the alliance.

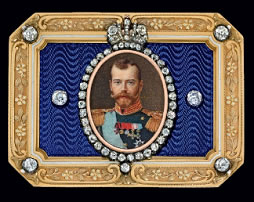

1913 Nicholas II Imperial Presentation Snuff Box

(Courtesy Christie’s)

Nicholas II Imperial Presentation Snuff Box

(Courtesy Christie’s)

An Imperial presentation snuff box (right, lot 238) is one of 68 boxes with ciphers made during the reign of Nicholas II by the firm of Fabergé. This category of boxes was awarded for special service rendered or to commemorate an anniversary in the recipient’s career, and is similar to those with a miniature portrait. The box sold to Russian billionaire Alexander Ivanov on November 29, 2010, for £97,250 ($151,905).

Dr. Tillander-Godenhielm advises that Imperial presentation boxes were made with blank cartouches. The clerks in the Cabinet having received an order to furnish a box at (for example) 3,500 rubles selected a box from their shelf. The price of it may have been 1,500 rubles, so they took brilliants from their stock costing 2,000 rubles and sent the box to jeweler Carl Hahn who set the stones into the box. The oval with either miniature portrait or cipher was also mounted into the box at this same time. After 1911, the jeweler Carl Blank received most of these commissions.

There were a total of 228 new snuff boxes acquired during the reign of Alexander III. Only three portrait boxes awarded by Alexander III seem to have survived, the two pictured above and a further box now in the Gokhran deposit, the State Precious Metals and Gems Repository in Moscow. The last mentioned box is of an earlier date, it has possibly been recycled a number of times or has remained on hand until the 1880’s when a miniature portrait of Alexander III by the miniaturist Alexander Matveevich Wegner was placed in the cartouche.

After the death of an Emperor, the Imperial Cabinet had boxes in stock from the previous reigns; Alexander II fell victim to an assassination plot and Alexander III died at the young age of 49, therefore, the Imperial Cabinet in 1894 had quite a few snuff boxes in stock when Nicholas II ascended the throne. Many of the boxes presented between 1894-1917 were thus older ones.

Research on portrait boxes in the reigns prior to Tsar Nicholas II continues by Dr. Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm. Our thanks to her and Dr. Daniel L. Hodges for sharing their information in this Fabergé Research Newsletter.

HER IMPERIAL MAJESTY ALEXANDRA FEODOROVNA has the benevolence of ordering in HER AUGUST NAME one jetton Standart, delivery without delay, with the Roman numeral ‘X’ and the years ‘1896-1906’ on the verso. On completion the badge shall be delivered to the Chancellery of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna (at the Winter Palace). Signed: Prince Putyatin

The Imperial Family on the Yacht Standart, ca. 1907

(Courtesy OTMA Forever)

To identify who was mentioned in the document about the Fabergé jetton, we made an educated guess on Anichkov – he is general-lieutenant Milii Milievich Anichkov (1848 – after 1917), who was the Assistant Chief of the Palace Administration and later Director of the Court Marshal’s department. The Princess offering a helping hand was Princess Sophia Sergeevna Putyatina, neé Paltov (1866 – died in Paris in 1940), wife of Mikhail Sergeevich Putyatin. We can also suggest that Vladimir Nikolaevich Nikitin (1848-1922) is the general of artillery, who from 1906 to 1908 was chief of the First Artillery army. His daughter Lidia Vladimirovna was maid-of-honor of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna.

Sketch of the Flag-shaped Jetton with a Double-headed

Eagle Based on Putyatin’s Drawing

(Courtesy of the Authors)

According to Fabergé researcher Valentin Skurlov, another jetton was sold on the 27th of September, 1907. It is named on the account Standart and is described as a jetton with a golden flag and an enameled eagle, is lacking the name of a recipient, has on the verso and the years, 1896 and 1906. The Empress paid 22 rubles on the account, which was half of the total cost of 44 rubles. It was commissioned from Fabergé by Tsar Nicholas II and Empress Alexandra Feodorovna. Skurlov suggests it was a special jetton since it was twice as expensive than others made later.

Boinovich, A. and Yu. Sibirtsev, Istoria Russkogo Flota v Znakakh I Zhetonakh [History of Russian Fleet in Tokens and Badges], 2009, p. 66, write that a special token for 10 years of work on the yacht Standart was approved in 1906, and another one in 1911 – for 5 years of service on the yacht Standart. It appears only a handful of persons received these jettons.

The puzzle of this story still remains unsolved – who was decorated with this award made by Fabergé in 1907?

The editors asked Dr. Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm to share her observations on Fabergé turkeys after we learned she had handled the turkey discussed in the Fall 2010 issue of the Fabergé Research Newsletter several times over the past 30 years. She explained Fabergé craftsmen worked as a team, developing the idea for an object, making a working drawing for it as well as a wax model, selecting the most characteristic hardstone material, and assembling the object in the workmaster’s shop. The genius of Fabergé was his talent of using new and modern techniques to create an object which still looked as if it was made by a single pair of hands.

A search of the Fabergé literature and auction catalogs brought to light three turkeys with slight variations in their final form. It is known the turkey in the 2010 auction belonged to a member of the Nobel family, who sold it to the famous antique shop Magaliff in Stockholm. Two of the turkeys have been identified with the gold mark of 72 zolotniki. All three turkeys below are made of the finest obsidian, lapis lazuli, purpurine, have diamonds eyes, and the gold feet are marked H.W. (Henrik Wigström, 1862-1923).

Dr. Tillander-Godenhielm wonders if anyone is aware of a Denissov-Uralski invoice to Fabergé?

Fabergé Turkeys

Christie’s London June 8, 2010

(Lot 177 $280,599)

Christie’s Geneva May 10, 1989

(Lot 103 SFr 71,500)

Royal Collection of Queen

Elizabeth II Commissioned

by King Edward VII

Important Russian Enamels and Fabergé from a New York Private Collection

Kovsh or drinking vessel in the shape of a bird with a golden beak sold for $242,500 (four times the low estimate). It is one of very few enamel pieces rendered in a rich range of colors and with areas of shading not polished to a high gloss, but instead rendered matte through exposure to hydrofluoric acid. This style was used in the Moscow Fabergé workshops and resembles an unglazed ceramic body.

Bird-shaped Kovsh, Imperial Parasol Handle

(Courtesy Sotheby’s)

Kenneth Snowman in his 1962 book writes, the parasols and walking-sticks carried by Russian ladies and gentlemen of discrimination were generally topped by one of the exquisite conceits from Fabergé’s. The editors asked Geoffrey Munn of Wartski London to share how he determines if it is a parasol, cane, or walking stick handle, since functional wooden mounts have disappeared in the intervening years, and some subsequent owners have converted handles into a desk seals. His response: They are defined by the width of the mount. Parasols usually have very fine stems since they were not required to take the weight of the owner, however, canes were.

December 6, 2010 Hôtel des Ventes, Geneva

Documents Impériaux: Collection Thormeyer

The largest collection of Romanov family papers ever put up for auction, consisting of 2,000 letters, postcards and photographs sent by the last Russian tsar’s siblings to their private tutor, Ferdinand Thormeyer, was sold at auction for $390,000 (four times its high estimate).

February 3, 2011 Richardsons Auction in Bourne, Lincolnshire, United Kingdom

A copy of Bainbridge, Henry Charles, Peter Carl Fabergé (London, 1949) with a handwritten note in the book by Fabergé first-born son, Eugène, was sold for £85. The inscription reads: I am much pleased that Bainbridge has written such an interesting book about my father. Eug. Fabergé London, Nov. 1949. His address is listed as 23 Rue Saulmier, Paris. Eugène Fabergé fled from the Soviet Union to Paris in 1921 where he set up a jewelry business (Fabergé et Cie) with his brother Alexander and others. It had limited success and was closed in 1960 when he died. (Courtesy John Jenkins)

April 14, 2011 Auktionshaus Dr. Fischer, Heilbronn, Germany

Russian Art, Fabergé & Icons

(Updates are posted in Exhibitions on the Fabergé Research Site)

March 30 – July 24, 2011 Exhibition Hall of the Assumption Belfry, Moscow Kremlin

Gemstone Treasures: Carl Fabergé and the Russian Stonecutters

Exhibition will showcase masterpieces of Carl Fabergé with a central display of six Imperial Easter Eggs from the Kremlin Museums, the Fersman Mineralogical Museum, and private collections. Also exhibited will be objects by Fabergé contemporaries – Ural stone-carving masters Alexey Denissov-Uralski and Abner Sumin.

May 10 – 20, 2011 Wartski, London

Japonisme: The Goldsmith and Japan from Falize to Fabergé

Exhibition, spanning the fifty years from 1867 to 1917, is the first devoted to the influence of Japanese works of art on Western jewellers and goldsmiths. Included are a hardstone Japanese flower study poised on a miniature table by Fabergé, and two frogs carved in the Fabergé’s shop.

July 9 – October 1, 2011 Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond

Fabergé Revealed

The entire VMFA collection of Fabergé and other jewelers of the time will be shown with a number of key loans from prominent collectors in the new special exhibition galleries. This exhibition will only be shown in Richmond. Collecting Fabergé Today: The Hodges Family Collection organized by the New Orleans Museum of Art will be the companion exhibition before it moves to the Frick Art and Historical Center, Pittsburgh, PA.

August 1 – September 25, 2011 Queen’s Gallery, London

Royal Fabergé

The exhibition at the annual Summer Opening of Buckingham Palace brings together masterpieces by Carl Fabergé, from Imperial Easter Eggs and dazzling jewel-encrusted boxes to miniature carvings of favorite royal pets, and reveals how the world’s finest collection of work by the Russian goldsmith and jeweler has been created by successive generations of the British Royal Family.

October 22, 2011 – January 15, 2012 Frick Art and Historical Center, Pittsburgh (PA)

Fabergé: The Hodges Family Collection

Over 100 objects from the first significant collection of Fabergé assembled in America in decades will be shown.

Joyce Lasky Reed, 76, championed the causes of the non-profit Fabergé Arts Foundation with offices in Washington (DC) and St. Petersburg, Russia. For 20 years she poured her heart and soul into the preservation of the cultural heritage of the Russian city and in particular, the works of Fabergé. Never to accept ‘No!’ as an answer, Joyce found a way to make her dreams come true and we supported her in each and every new and exciting venture.

John Webster Keefe, 69, always up for a good story that needed to be told, shared his art history knowledge in Fabergé publications about the Matilda Geddings Gray Collection at the New Orleans Museum of Art which later moved to the Cheekwood Museum of Art in Nashville, Tennessee. More recently he authored the catalogue raisonné for the Hodges Family Collection. His personal collection of 19th century art and decorative objects, begun as a teenager, encompassed drawings, paintings and small sculpture, and at the time of his death, it was on view at the Meadows Museum of Art in Shreveport, Louisiana.

John Traina, 79, a man who lived life to the fullest was a collector at heart – 550 Fabergé and Russian cigarette cases and smoking accessories acquired in the late 70’s – early 80’s, wagons, buggies, and old carriages, a landmark San Francisco firehouse and two vintage 1930’s pump engines, art, automobiles, etc. In the Fabergé Arts Foundation Newsletter (Spring 1998) after Traina’s book, The Fabergé Case, was published, he shared his opinion about the art of Fabergé – it remains a living subject, about which contemporary research and the new information pouring out of Russia yields constant surprises. It is a gift from the old Russia in which the new Russia (and the New Russians) can take great pride, and even delight.

Reed with Lyudmila Bakayutova

(St. Petersburg Liaison)

John Webster Keefe

John Traina

Fiona Bruce, presenter of the British Antiques Roadshow, was asked in November 2010 to choose her ten greatest stars of the show. Number 6 was an elaborate and ornate kovsh by Fabergé valued between £600,000 and £700,000. The Daily Mail (London) states the drinking vessel was presented to the ward of the HMS Talbot by Tsar Nicholas II in recognition of the ship’s help after a battle in the Russo-Japanese War (1904-05).

New website resources from Royal Russia News include a biographical directory of 39 Grand Dukes of the Russian Imperial Family illustrated with portraits. A similar page is in preparation on the Grand Duchesses of Russia separated into those holding the title by birth, and by marriage. Romanov and Russian Links is a compilation of helpful websites for researchers.

There is a new sparkle to eight Fabergé Easter eggs. At the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond, five eggs have undergone a restoration and conservation process. The 1899 Pansy Egg in a private collection was restored for the 2008 Cleveland Fabergé exhibition. The delicate process and subsequent new luster of the 1908 Peacock and 1907 Yusupov Eggs owned by the Fondation Edouard et Maurice Sandoz Collection in Lausanne, Switzerland, are illustrated in a web article.

Further information about this delicate task is in Carol Aiken’s essay, “Imperial Easter Eggs: A Technical Study” in von Habsburg and Lopato, Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs, 1993, 76-83. Ms. Aiken in a newspaper interview (Richmond News Leader, February 7, 1983, 14) described the cleaning of some 300 Fabergé objects in preparation for a joint exhibition of the Forbes Magazine Collection and the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts Collection. Two methods used in maintaining Fabergé pieces are bathing them gently in liquids, or dismantling them for cleaning.

Adulf Peter Goop, a Russophile and resident of Vaduz, Liechtenstein, donated his collection of eggs, including the Apple Blossom Egg to the Liechtensteinischen Landesmuseum in May 2010. The egg was made by Fabergé in 1901 for the Russian industrialist Alexander Kelch as a gift for his wealthy wife Barbara. Goop acquired the egg at a 1996 auction. At the museum ceremony he stated his wish was to donate his extensive collection to his country and its citizens for future generations to treasure.

Charron, Caroline. Fabergé, de la cour du tsar à l’exil, 2010. Paperback novel in French written by a journalist with a cover illustration of the Tsarevich Egg.

Faber, Toby. Пасхальные яйца Фаберже, 2010. Russian translation of the author’s well-researched and comprehensive account of his 2008 publication, Fabergé’s Eggs: The Extraordinary Story of the Masterpieces that Outlived an Empire. Readers are advised the Coronation Egg illustrated on the cover is embellished and not the original Fabergé egg.

Lost Fabergé Eggs published by Books LLC (2010) is a 16-page pamphlet with minimal detail for eight missing Fabergé eggs. The text is copied from two standard reference sources – the Fabergé’s Imperial Easter Eggs website, and Lowes and McCanless, Fabergé Eggs: A Retrospective Encyclopedia (2001), and presented in this short hardcopy format with a hyperlinked version in Wikipedia.

Moore, Andrew [pseud]. The St. Petersburg Collection by Theo Fabergé (Third edition published in 2009) includes useful research tools, i.e., family history details about Carl Fabergé and his son Nicholas, an updated Fabergé family tree, and listings of Theo and Sarah Fabergé creations.

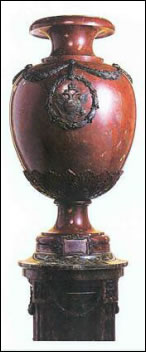

Design Sketch and Fabergé Urn

(Courtesy Christie’s London and New York Stock Exchange)

“On June 21, 1904, the New York Stock Exchange was presented with a resplendent gift from the Imperial Russian Government: a stone and silver urn crafted by Carl Fabergé …” so begins the history of this gift (Dimensions: Total height (87”), height of urn (40”), base (24” diameter), urn (20” across at widest point) on display in the Board Room of the NYSE. It is carved from red jasper, trimmed with silver and sits on a pedestal of green jasper. The urn was a token of appreciation from Tsar Nicholas II to this American financial institution “for its help in floating a $1 billion loan in 1902 to the Russian government, a large amount for its time”.

“Underwritten by a prestigious syndicate of investments banks including J. P. Morgan & Co., it was a dramatic indication of the growing importance of the New York financial markets … the bonds were finally suspended from trading on the NYSE in 1921.”

Wartski, London. The Last Flowering of Court Art: A Russian Private Collection of Fabergé, 2010. Every object shown in the exhibition with the same name is beautifully illustrated with explanatory text.

In the Memoirs of HRH Prince Christopher of Greece (1938, 62-3), there is more about the history of the nuptial crown:

Peter Schaffer of A La Vieille Russie suggested a German edition of the Fersman Portfolio is extant. Another reader advised Russian editions are in use at the Diamond Fund Exhibition in Moscow.

Anne Odom, curator emeritus, Hillwood Estate, Museum, and Gardens, corrected our error. Princess Paley lost her lawsuit and the whole contents of the Paley Palace were sold in July 1929 (Treasures into Tractors, 2009, 18). All similar lawsuits were lost by their owners, whether in Germany, Britain, or the United States. The threat of lawsuits did make some countries more cautious, especially France, but the Western public, their governments, and courts were never very sympathetic toward members of the Russian aristocracy. On the nuptial crown she added, there is

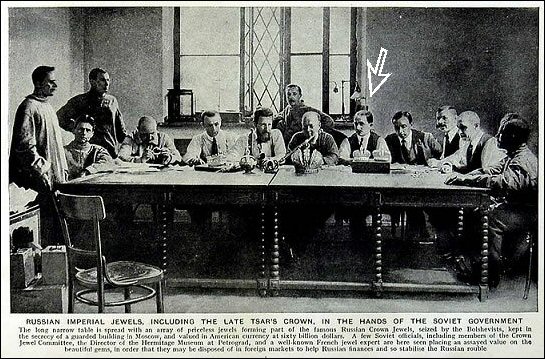

A reader found another photograph of Agathon Fabergé and the Russian crown jewels, apparently taken in the same room as the photograph in the Fall issue. In front of Agathon are the two smaller crowns the Empresses wore at the coronation of Nicholas II in 1896.

Cigarette Cases

(Courtesy Sotheby’s and C & M Photographers)

Have you ever admired a Fabergé fan, and wondered about the connection between a fan and the Russian jewelry firm of Fabergé? High quality fans, a necessity for ladies in the late 19th century, were made in France with lace imported from Belgium, and decorated in the country of sale by fashionable and usually royal jewelers. A succinct explanation of the artistic connection in Williams, et al. Enamels of the World, 2009, 386, states:

Watteauesque-style Fan, J. Donzel Fils Fan, both with Fabergé Guards

(Photos: C & M Photographers)

The second fan in the collection is painted on parchment, signed J. Donzel fils, and depicts the Fountain of Youth and Venus Triumphant surrounded by amorini while the reverse is decorated with gilt scrolls and painted flowers. The French Donzel family specialized in fan-painting and worked for all the leading Paris fan makers. Sold at the Sotheby London auctions (November 22, 1956, Lot 98, and July 9, 1959, Lot 81). Fabergé dealer A. Kenneth Snowman in 1962 confirmed the mark as AH (August Holmström, 1829-1903, his shop was continued by his son), described the Fabergé guard of translucent coral color with dark sepia plant designs, and included the fan as part of a collection formed by Madame Elisabeth Balletta (? – 1959). She was under contract from 1891-1905 as an actress with the St. Petersburg Mikhailovksy Theatre, a venue for French and Russian drama and comedy. Later provenance details in the literature of Fabergé suggest it was a gift from Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich (1850-1908), Admiral of the Russian Navy until 1905, and an admirer of Madame Balletta.

Readers aware of other Fabergé fans are invited to contact the Editors so this topic can be explored in more detail.

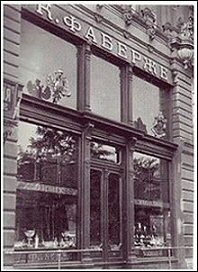

Several readers have tried to find the location of the Odessa Fabergé branch. It is known Fabergé’s retail store opened in 1900 and closed in 1918, and its small workshop existed between ca. 1900 and 1903. At Deribasovskaya street 33 (Дериба́совская) the house number of the “Passage”, a commemorative plaque (below right) has been placed on the building with the name Karl Fabergé and the address. It is still not known, if the shop was located on the inside or outside of the Passage. Except perhaps for some matching building stones, not a trace has been found of the building shown in an old Fabergé archival photo (below left). The shop in the middle picture with an advertisement for Fabergé Eggs was photographed in April 2010 not far from the commemorative plaque. Does the shop owner perhaps know?

Archival Photo Fabergé Shop Odessa

(Date Unknown)

Jeweler in Deribasovskaya Street Next

to an Entrance to the Passage

(April 2010)

Deribasovskaya street 33, Odessa

(September 2010)