On July 9, 2011, a new catalogue raisonné under the leadership of Dr. Géza von Habsburg and with contributions from international scholars will be published. In addition, the Fabergé Revealed exhibition will include key loans from prominent international collectors.

Stories abound about VMFA’s world-renowned collection of Russian Imperial Easter eggs by Carl Fabergé. Interesting facts and fiction from a museum press release (May 13, 2009) include:

One story holds that Lillian Thomas Pratt hid her treasures away in hat boxes and shoe boxes at Chatham Manor, her home on the Rappahannock River near Fredericksburg, Virginia, between 1933 and 1945.

Another tale holds that in 1947, Thomas Colt, Jr., who was the Museum Director when Mrs. Pratt died, drove what Time Magazine in a flurry of national publicity called the “Royal Haul” to Richmond in the back of his Chevrolet station wagon.

Still another story tells of the time in the 1960s when the museum’s chief spokesman took a couple of the Imperial Easter eggs on a flight to New York for an appearance on NBC’s Today show – and that he transported them by hand in nondescript carriers to avoid unwanted attention. Some of the stories are true, and some are not.

But it’s safe to bet that the scores of objects in VMFA’s Pratt Collection – including five spectacular Imperial Easter eggs worth untold millions today – have been treated in anything but a casual manner since they first went on view in Richmond in 1953.

Pratt Fabergé Eggs

(Courtesy Virginia Museum of Fine Arts)

- The 1896 Rock Crystal Egg (also known as the Egg with Revolving Miniatures) was given to Tsarina Alexandra Feodorovna in the year of Tsar Nicholas’ coronation, and represents residences of significance in the life of the Tsarina. The egg is topped by a 26-carat emerald (1).

- The 1898 Pelican Egg is made of red gold and is topped by a diamond-studded pelican, a symbol of self-sacrifice. Nicholas gave it to his mother, the Dowager Empress Marie Feodorovna, who was patron of the eight educational institutions represented inside the egg (2).

- The 1903 Peter the Great Egg was a present to Alexandra Feodorovna, the wife of Tsar Nicholas II. It is made of gold and platinum and set with diamonds and rubies. When the top is opened, a tiny replica of a statue of Peter the Great arises from inside (3).

- The 1912 Tsarevich Egg, another gift to the Tsarina from her husband, is a fantasy of lapis lazuli and gold. Concealed inside is a diamond-encrusted double-headed eagle that frames a portrait of their only son Alexis in a sailor suit (4).

- The 1915 Red Cross Egg, another gift for Nicholas’ mother, is made of white opalescent enamel with a scarlet cross on each side, a tribute to her presidency of the Russian Red Cross. Inside are miniatures of members of the Romanov family wearing Red Cross uniforms (5).

But what is the truth behind the stories about the Pratt Collection?

Mrs. Pratt did not hide her collection away in hat boxes and shoe boxes. Fifty years after her bequest, the museum found evidence of a large display cabinet, one of several pieces of furniture expressly designed for Chatham Manor to display Mrs. Pratt’s collection in all its sparkling glory.

VMFA Director Colt did indeed drive the Pratt Collection to Richmond in his station wagon, although he packed carefully and did not treat the transfer casually. Once the treasures were in Richmond, they were stored in a bank vault until a suitable gallery was constructed.

It is true that in 1968, accompanied by a museum security guard, Fred Haseltine – who was then an assistant to the museum’s director – took a small portion of the collection to New York in nondescript carriers for a 10-minute Today show presentation with Barbara Walters. Times change, however: Museum officials today say such a trip would be unthinkable. (Article courtesy of Virginia Museum of Fine Arts)

Russian Art

A carved lapis lazuli and gold dolphin footed bowl is the highlight from the Estate of Frances H. Jones comprising over 40 lots of Fabergé acquired in the 1960s and 70s, and formerly in the Lansdell K. Christie collection. A design sketch by the workshop of Henrik Wigström for 1913 is extant. The auction contains an additional 30 lots by Fabergé.

Lapis Lazuli Bowl and Sketch

(Courtesy Sotheby’s)

Russian Art

More than 60 works by Fabergé include a Rococo style guilloché enamelled desk clock by Michael Perchin in its original box, a collection of jewelry and hardstone animals from a Massachusetts collector, and a private collection of photograph frames. In 2009 Christie’s New York established a market share of more than 60% for works of art by Fabergé.

Rococo Desk Clock

(Courtesy Christie’s)

The Russian Sale

June 9, 2010 Sotheby’s London

Russian Works of Art, Fabergé and Icons

(Updates are posted in Exhibitions on the Fabergé Research Site)

Fabergé dealers, A La Vieille Russie of New York and Wartski of London, will exhibit at the new, larger and broader venue replacing the defunct Grosvenor House Antiques Fair.

Fabergé Cufflinks by Galina Korneva and Tatiana Cheboksarova

Interest was high at the November 20, 2009, Sotheby’s London auction, especially for a wonderful collection of cufflinks belonging to Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich and Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna. Recently we found archival information for six more pairs of Imperial cufflinks created by Fabergé based on a commission dated January 14, 1914.

Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna (1895-1918), the first of four daughters of Tsar Nicholas II and Alexandra Feodorovna, celebrated her 18th birthday on November 3 (16 Old Style), 1913. She had finished her lessons at home and the Imperial family decided to reward some of the teachers with presents. The information about this order is in the St. Petersburg Russian State Historical Archives (Fund of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna’ Chancery).

First of all – as it often occurred – officials from the Chancery sent their request to other Chanceries to find out if precedents existed. This time the request was forwarded to the Chancery of the children of the late Tsar Alexander III to determine what types of presents were given in the same situation to teachers. From official letters it becomes clear, these presents were not given from the Chancery to teachers as with the children of Alexander III and also with the Duchess of Imperial blood Irina (1895-1970), daughter of Grand Duke Mikhail Alexandrovich and Xenia Alexandrovna. However, Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich gave autographed photographs in frames decorated with precious stones. In 1903, Grand Duke Mikhail Alexandrovich (1878-1918) gave to his teacher of jurisprudence, K. Pobedonostsev (1827-1907), his portrait in a frame for 100 rubles.

After reading about archival precedents Empress Alexandra Feodorovna was most graciously pleased to give permission to her daughter Olga Nikolaevna to reward her teachers: Archpriest Alexander Vasilyev (1868-1918), teacher of Scripture to all five of the children of Nicholas II from January 1, 1910, received a valuable gospel with a decorated cover, but not by Fabergé. The chancery document contains interesting details about Alexandra Feodorovna’s special choice for the gospel decoration. In October 1912, Vasilyev was the presbyter of the Vernicle Image of the Saviour Church in the Winter Palace, and in 1913 the dean of the Theodore Icon of the Virgin Cathedral built in Tsarskoye Selo. Then in 1914, Vasilyev became confessor of the Emperor and Empress. He was ill when the Imperial Family was sent to Siberia, could not follow them and was shot after being arrested in 1918.

Fabergé after receiving the commission in January of 1914 had to submit the drawings for final approval by Empress Alexandra Feodorovna before March 13. Each pair was to be enamelled and contain no precious stones. Rewarded with Fabergé cufflinks were A. Konrad, teacher from April 1902, Korzhavin, riding teacher from 1902, Petr Petrov (1858-1918), teacher of Russian from January 1903, Pierre Gilliard (1879-1962), French teacher from 1905, Konstantin Ivanov, teacher from October 1908, and Charles Sydney Gibbes (1876-1963), English language teacher from October 1908. The initials of Olga Nikolaevna and the beginning and ending dates of service had to be placed on the cuff links. The order was executed on time and each pair cost between 100 to 125 rubles.

Perhaps this information will be useful in identifying the unusual presents given to the teachers by Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna, oldest daughter of the last Russian Tsar.

Pierre Gilliard with His Pupils, the Grand Duchesses Olga (left)

and Tatiana Nikolaevna at Livadia in 1911

(Courtesy Beinecke Library)

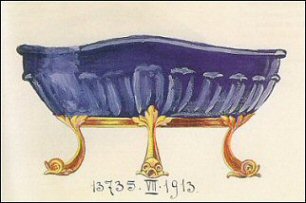

Charles Sydney Gibbes as Father Nicholas

in His London Parish after 1937

(The House of Special Purpose)

Gibbes, an Englishman, who during his ten years with the Imperial family became very fond of his pupils, also followed the family into exile. Returning to Great Britain in 1937, he was established as perhaps the first English 0rthodox Abbot – he took the name Father Nicholas in honor of the former Tsar – in a parish in London. A chapel known as Saint Nicholas House in London (now part of the Wernher Collection in Greenwich) contains several icons and mementos of the Imperial family which he brought from Ekaterinburg. Based on personal papers of Gibbes the book, A House of Special Purpose: An Intimate Portrait of the Last Days of the Russian Imperial Family (1975), was published twelve years after his death.

“Glittering Competition: The Rivals of Fabergé” in the April 2010 issue of Magazine Antiques discusses the Russian silver ware competitors of Fabergé in the nineteenth century.

No clear-cut answer surfaced, and therefore, modern collectors still struggle with identifying the objects made by these two jewelers. The existence of fakes, nicknamed Fauxbergé by Dr. von Habsburg, further complicates the identification process.

Cody (9 cm)

Cartier (6.6 cm)

VMFA (4.5 cm)

Mango (9 cm)

Fabergé Rabbit

(Courtesy Christie’s)