Newsletter 2015 Summer

Cipher EII (1762-1796) of Empress Catherine II

(Ekaterina II Alekseevna) (1729-1796).

Courtesy McFerrin Collection. Paired with a portrait of

Princess E. N. Orlova by Rokotov c.1779.

Courtesy The State Tretyakov Gallery.

Cipher M (1796-1801) of

Empress Maria Feodorovna (1759-1828).

Courtesy Hillwood Estate, Museum and Garden.

Paired with a portrait of Princess E. A. Dolgorukaia

by Borovikovskii 1798.

Courtesy The State Tretyakov Gallery.

Cipher EM (1801-1825) of

Empress Elizabeth Alekseevna (1779-1826)

and Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna (1759-1828).

Courtesy Wartski. Paired with a portrait of

Countess E. N. Potocka by Mitoire 1820s.

Courtesy Tver Regional Art Gallery.

Cipher AME (1825-1826) of

Empress Alexandra Feodorovna

(1798-1860),

Dowager Empress Maria

Feodorovna (1759-1828), and

Dowager Empress Elizabeth

Alekseevna (1779-1826).

Portrait of an unknown

maid of honor.

Courtesy Peter Collingridge.

Cipher AM (1826-1828) of Empress

Alexandra Feodorovna (1798-1860)

and Dowager Empress Maria

Feodorovna (1759-1828).

Courtesy The State Historical Museum,

Moscow. Paired with a portrait of

Countess M. A. Olsuf’eva

by Pluchart 1839.

Courtesy The State Tretyakov Gallery.

Cipher A (1828-1855) of

Empress Alexandra Feodorovna (1798-1860).

Courtesy of the descendants of Countess

Adelaide Armfelt. Paired with a portrait of

Princesses S. D. and E. G. Volkonskaia by

Brallow 1843.

Courtesy The State Tretyakov Gallery.

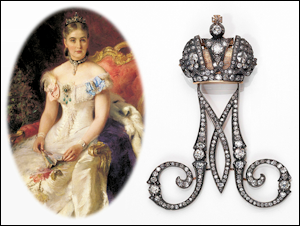

Cipher MA (1855-1860) of

Empress Maria Aleksandrovna (1824-1880) and

Dowager Empress Alexandra Feodorovna (1798-1860).

Courtesy Christie’s. Paired with a portrait of

Empress Maria Aleksandrovna by Robertson 1849.

Courtesy The State Hermitage Museum

and a portrait of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna

by the studio of George Dawe 19th c.

Courtesy Sotheby’s.

Cipher M (1860-1880) of

Empress Maria Aleksandrovna (1824-1880).

Courtesy Bonhams. Paired with a portrait of

Princess M. M. Volkonskaia by Makovskii 1884.

Courtesy The National Museum of Georgia, Tbilisi.

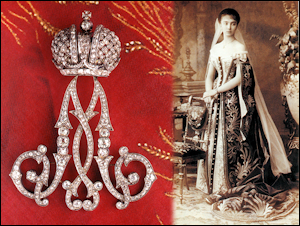

Cipher M (1881-1894) of

Empress Maria Feodorovna (1847-1928).

Courtesy the descendants of Sophie von Kraemer.

Paired with a photograph of Princess E. N. Obolenskaia.

Courtesy the Internet.

Cipher MA (1894-1917) of

Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna (1847-1928)

and Empress Alexandra Feodorovna (1872-1918).

Courtesy Christie’s. Paired with a photograph

of an unknown maid of honor.

Courtesy the Internet.

Note: The dates listed in the captions are:

1) the years of each reign, during which a maid-of-honor cipher and Portrait Badge of an empress was awarded

2) the birth and death year of each empress.

The insignia of the maids of honor consisted of the empress’s initial in diamonds surmounted with the imperial crown. This cipher was worn on the left shoulder suspended from the light blue ribbon of the Order of Saint Andrew. The design was revised at the very beginning of each new reign or at the death of a dowager empress. Thus, at the death of Empress Catherine II, the insignia was changed from the initial EII (for Ekaterina II) to M, for the new empress Maria Feodorovna, consort of Paul I. In 1801, when Alexander I ascended the throne, the cipher was designed with two initials, E and M, those of his mother, Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna, and of his wife, Empress Elizabeth Alekseevna. At the death in 1825 of Alexander I, the consort of the new emperor, Alexandra Feodorovna, from December 1825 to May 1826, had two dowager empresses at her side. The cipher, therefore, was composed of the three initials A, M, and E. Following the death in 1826 of Dowager Empress Elizabeth Alekseevna, and until 1828, when Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna died, it had the two initials A and M. From 1828 until 1855, it was the single initial A of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna. Between 1855 and 1860, there were once again two empresses, and the cipher was designed with the initials M and A. Between 1860 and 1880, it was a single M for the consort of Alexander II, Maria Aleksandrovna. Between 1881 and 1894, the single M reappears, this time for Maria Feodorovna, consort of Alexander III. (It should be noted that the wives of Paul I, Alexander II and Alexander III, all of whom were given the name Maria upon conversion to the Orthodox faith, had their own personal design of their respective initial M). The last reign once again saw an M and an A for Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna and Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, wife of Nicholas II. On this occasion, the initials were in the Old Russian style.

The ciphers were made by the foremost jewelers of each reign. Thus, during the reign of Catherine II, the makers were undoubtedly her court jewelers the Duval brothers. The firm of Keibel took over the bulk of this production during the reign of Alexander I. Nicholas I commissioned ciphers mainly from the jewelers Breitful and Bolin. The firms of Bolin and Saefftigen continued the production under Alexander II along with the established jewelers Keibel and Butz. During the reigns of Alexander III and Nicholas II, the firms of Bolin, Butz, Hahn, and Koechly were the main providers of these objects. In the final years, beginning around 1910, it was the workshops of Butz, Blank, and occasionally Johansson. It may come as a surprise that Fabergé, the leading jeweler of the last two reigns, was not among them. This was no doubt by Fabergé’s own choice. He did not specialize in serial production of this kind.

Measuring roughly 3 1/2 inches (9 cm), they are made of gold (56 zolotniki, equivalent to today’s 14 karat) and silver, into which the brilliant-cut diamonds are set. The original recipients are known in many cases, increasing both their historic and monetary value. In Finland, a former grand duchy of the Russian Empire, a fair number are still preserved by the families of the initial owners. A portrait of their ancestress in court costume wearing her cipher takes pride of place in their homes.

The insignia of ladies of honor and maids of honor of the bedchamber consisted of the miniature portrait of the empress or empresses, if one or even two dowagers were still alive. It was set in a diamond frame and like the ciphers worn on the left shoulder suspended from the light blue ribbon of the Order of Saint Andrew. Only a handful of examples survive, although many can be seen in portraits of the time.

Portrait badge of Empress Elizabeth Petrovna

(1741-1761). Detail of the portrait of Countess

N. D. Razumovskaia by Hauser 1746.

Courtesy Wikipedia.

Portrait badge of Empress Catherine II

(1762-1796). Detail of the portrait of Princess

E. N. Orlova by Rokotov c.1779. Beneath

it one can see her EII maid-of-honor cipher;

and to the left, the sash of the

Order of St Catherine

(at that time there was only one class of the order).

Courtesy The State Tretyakov Gallery.

Portrait badge of Empress Alexandra

Feodorovna and Dowager Empress Maria

Feodorovna (1826-1828). Detail of the portrait

of H.S.H. Princess T. V. Golitsyna by Riss 1835.

Courtesy The State Historical Museum, Moscow. Beneath

it one can see the maid-of-honor cipher of Empress Maria

Feodorovna (1796-1801); and above it to the right, the

smaller cross of the Order of St Catherine.

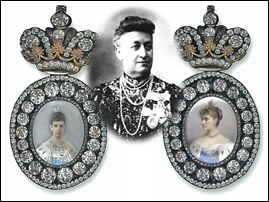

Portrait badge of Empress Maria Feodorovna

(1881-1894) and of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna

(1894-1917).

Courtesy Sergei Patrikeev. Paired with a photograph

of their recipient, E. A. Naryshkina, who received

the first in 1891 and the second in 1912.

Courtesy the Internet.

Portrait badge of Dowager Empress Maria

Feodorovna and Empress Alexandra Feodorovna

(1894-1917). Presented to Countess

E. P. Sheremeteva in 1912.

Courtesy Hillwood Estate, Museum and Garden.

Portrait of Aurora Karlovna Karamzina,

née Stjernvall (1808-1902), with a cipher of

her empress, Alexandra Feodorovna (1828-1855);

a smaller cross of St Catherine, which she received

in 1883; and a portrait badge of Dowager Empress

Maria Feodorovna and Empress Alexandra Feodorovna

(1894-1917), which she received in 1898.

(The portrait badge depicted here is the one

presented to A. S. Albedinskaia in 1896.)

Courtesy Sergei Patrikeev.

Grand Mistress and Mistress of the Court

The grand mistress of the court (обер-гофмейстерина / ober-gofmeisterina), and the mistress of the court (гофмейстерина / gofmeisterina), were chosen from among the ladies of honor. They were generally from the highest aristocracy, with lifelong experience at court. These ladies were appointed to handle the most important aspects of the empress’s household and were in attendance at all official ceremonies. They served in very close proximity to the empress, as mentor, adviser, and in many cases confidante or even mother figure. All consorts of the Russian emperors since Catherine I were foreign princesses and the need for a close and reliable Russian-born female adviser was obvious, especially at the beginning of a new reign. They were without exception ladies of the prestigious Order of Saint Catherine (typically the smaller cross).

As with their male counterparts, these ladies had their own distinct “uniforms” instituted by Nicholas I in the 1830s. The costume of the mistress of the court consisted of a “Russian style” dress of gold-embroidered raspberry red velvet with a long train and an underskirt of white satin also richly embroidered in gold. The headdress was a kokoshnik of the same color velvet with a long white veil of lace or tulle.

Ladies of Honor and Maids of Honor of the Bedchamber

To be named a lady of honor (статс-дама / stats-dama) or a maid of honor of the bedchamber (камер-фрейлина / kamer-freilina) of the empress was a distinction bestowed on a very select group of individuals at court; those who had either served the empress for most of their life-many had been maids of honor in their youth-or were for some other reason held in high regard by the imperial family. The former was bestowed upon married ladies, the latter, on unmarried ones. Like the grand mistress or mistress of the court, these ladies were generally ladies recipients of the Order of Saint Catherine (smaller cross).

Their costume was of the same cut and design as that of the mistress of the court, with the dress and kokoshnik made of dark green velvet. There were no specific duties attached to either rank, nor were the ladies in question under any obligation to be present at court ceremonies.

Maids of Honor

The largest group of female courtiers were the maids of honor (фрейлина / freilina). They belonged to the most illustrious families of the empire, and their fathers were for the most part men of great merit who had served with distinction in either the civil service, the military, or at court. The nomination was not only an honor for the young lady, it was an indication of the esteem with which her father was regarded by the emperor. In effect, it can be looked upon as giving him another award. One can go even further and state that such an appointment was not only a mark of distinction for the immediate family, but for the family at large.

There were two categories: the maids of honor “of the city” (городские фрейлины / gorodskie freiliny), as they were familiarly known, and the maids of honor “of the suite” (комплектные или свитные фрейлины / komplektnyie or svitnye freiliny). The latter were generally few in number, and under the two last reigns, ranged anywhere from one to five at any given time. The former represented a much larger group, reaching a total of approximately 250 during the last reign. The number of appointments had risen steadily over the past century. Whereas Catherine the Great had the comparatively modest total of 17 maids of honor in 1795, by the first year of Alexander II’s reign (1855), there were already 150.

The maids of honor of the suite were instituted by Nicholas I in 1826 and were designated as being “attached to Her Majesty”. These ladies had extensive duties and generally served every other day. They consequently had their own apartment in specific suites of rooms in the imperial palaces. In retirement, they were given rooms in the Tauride Palace, until it was put at the disposal of the Duma in 1905.

Selection was based on a scrupulous analysis of the lady’s character. Discretion was high on the list of qualities for a candidate, and her family and circle of friends were also scrutinized. It was her responsibility to help her empress in every way possible, including assisting her with official correspondence, with the running of her charities, as well as being responsible for her mistress’s jewel boxes, which contained both her personal pieces as well as crown jewels chosen for her use. She was in attendance at court receptions, banquets, and evenings at the opera, theater, or in concert halls, where she took her place in the imperial box. During trips within the empire and abroad, one or two of these ladies were always part of the entourage.

Maids of honor “of the city” were so called because, as opposed to those “of the suite”, they were not required to live in the palace. Officially they were known as “maids of honor of Their Imperial Majesties the Sovereign Empresses”. In general appointed at the age of eighteen to twenty, they were already of marriageable age, and once wed, were obliged to “retire”. Nonetheless, they retained their entrée at court, regardless of her husband’s rank, and continued to wear their insignia at official functions for the rest of their life.

Their primary obligation was to serve the empress whenever called upon. Due to their substantial number, it was only occasionally. They were not paid for their services, but the distinction of being appointed gave them many privileges far outweighing any remuneration. The foremost was access to the imperial court, which permitted them to form an influential network of valuable contacts. Their costume, in the same style as that of the other court ladies, was of gold-embroidered crimson velvet.

In this summary of Maria Feodorovna’s eggs the status-quo in research for lost, found and revisited eggs is presented with illustrations, if known, as well as links to previous significant research. A major source of revised information is contributed by Will Lowes, co-author of Lowes and McCanless, Fabergé Eggs: A Retrospective Encyclopedia. Since the book’s publication in 2001, Lowes has continued to update the data for 66 eggs in four categories – Tsar Imperial, Imperial, Kelch and Other. For the nine Tsar Imperial eggs discussed in the current essay he is sharing his updates. In 2013, Annemiek Wintraecken and Christel Ludewig McCanless wrote about this topic in “Empress Marie Feodorovna’s Missing Fabergé Easter Eggs” for Royal Russia Annual No. 3, 89-96. The article was reprinted with gracious permission by Paul Gilbert, publisher and editor of the annuals.

Fabergé made the hen of gold, set with rose-cut diamonds, arguing that it would look like bronze otherwise and would not be beautiful. The sapphire egg was held loosely in the hen’s beak, and the wicker basket was made of gold and apparently decorated with rose-cut diamonds. The whole consisted of one sapphire egg costing of 1800 rubles out of 2,986 rubles, 50 rose-cut diamonds 8/32, 60 rose-cut diamonds 14/32, 400 rose-cut diamonds 5 1/4; gold, and two cases. Diamond weights are given in the old systems used by European jewelers. Was the egg possibly dismantled for the value of its stones?

- April 5 (OS), 1886. Sent to Tsarskoe Selo by courier and presented to Tsar Alexander III

- April 13 (OS), 1886. Would have been presented to Marie Feodorovna, a gift from Alexander III; cost 2,986 rubles, 25 kopeks. Housed in the Anichkov Palace

- September 16-20 (OS), 1917. One of forty or so eggs sent to the Armoury Palace of the Kremlin in Moscow by the Kerensky Provisional Government for safekeeping

- 1922. May have been transferred to the Sovnarkom, the Council of People’s Commissars

- 2015. Whereabouts unknown. There is no known illustration of it.

(Courtesy Wartski)

The Russian State Historical Archives material cited by Marina Lopato (Apollo, January 1984) describes the egg as an …Easter egg with a clock, decorated with brilliants, sapphires and rose diamonds – 2160 rubles. In March 2014, Wartski’s website noted research by Tatiana Muntian on the record of transfer in September 1917 from the Anichkov Palace to the Moscow Kremlin Armoury: …Art. 1548. ˜A lady’s gold watch, opened and set into a gold egg with one diamond. The latter on a gold tripod pedestal with three sapphires.’ Number 1644. Muntian’s research cited in von Solodkoff, Fabergé: Juweiler des Zarenhofs (Hamburg, 1995), yielded another description of this egg. The 1919 inventory of confiscated Imperial treasure describes it as a …Gold egg with clock with a circle of brilliants, gold stand, with three sapphires and diamond roses. And the 1922 transfer documents of confiscated valuables from the Anichkov Palace to the Sovnarkom says: …Gold egg with clock with diamond pushpiece, on gold pedestal with 3 sapphires and rose-cut diamonds roses.

However, on July 6, 2011, Annemiek Wintraecken reported a connection had been made with an object in the vitrine of the Dowager Empress Marie Feodorovna in the 1902 von Dervis exhibition in St. Petersburg, and an item sold at auction by Parke Bernet, in their New York sale of March 6-7, 1964:

Regrettably, the catalogue fails to give details of the maker’s marks, or dates. But this was not unusual; rather it was the norm for decorative arts catalogues of this period. Fortunately, the auction catalog carried an excellent image of the item for sale. It was without doubt, the same item as identified by Wintraecken’s research colleagues, Vincent and Anna Palmade, once the article in the image from the von Dervis exhibition was enlarged. The Palmades commented further:

They added: …It should also be noted the written Russian description talks about …an egg with a clock for the 1886 egg.

Then in March 2014, the London Fabergé dealer Wartski announced the Egg had been found. Wartski released the first color photographs of the Egg on its website, which describes the Egg thus:

Wartski advised they had purchased the Egg and sold it to an undisclosed bidder. In a flurry of word-wide newspaper articles, more specific details came to light. The first one written by Anita Singh for The Telegraph newspaper in London on March 18, 2014, based on an interview with Kieran McCarthy of Wartski carried the headline, The £20m Fabergé Egg That Was Almost Sold for Scrap.

An Internet publication, ecommercebytes.com reported on April 6, 2014:

In early 2015, thanks to two Russian scholars Drs. Galina Korneva and Tatiana Cheboksarova, an archival letter was found which had been written on May 4 (OS), 1887 by Modest Feopemtovich Solovyev, the Governor of the Office of Grand Duke Vladimir’s Court from 1881 to 1899, to Nikolai Stepanovich Petrov (1833-1913), who in 1887 was the Head of Cabinet of Alexander III. It reads:

By order of H.I.H. Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich an Easter egg with a clock and a stand in the style of Louis XVI was commissioned to the jeweler Fabergé. This egg is finished and was delivered to the Emperor. Today Fabergé sent an invoice of 2,160 rubles which H.I.H. commanded me to send to Your excellence. M. Solovyev.

Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich had been heavily involved in the creation of the First Hen Egg.

Kieran McCarthy of Wartski in a public lecture in English and Russian on June 4-5, 2015 at the Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia, gave his first-hand account of the rediscovery of the 1887 Third Imperial Easter.

- April 5 (OS), 1887. Would have been presented to Marie Feodorovna, a gift from Alexander III; cost 2,160 silver rubles. Housed in the Anichkov Palace

- September 16-20 (OS), 1917. One of forty or so eggs sent to the Armoury Palace of the Kremlin in Moscow by the Kerensky Provisional Government for safekeeping

- Between February 17-March 24, 1922. Transferred to the Sovnarkom, the Council of People’s Commissars, possibly bought by Hammer Galleries, New York

- March 6-7, 1964. Offered by Mrs. Rena Clark of New York at Parke-Bernet’s (New York) auction. Sold to a female buyer from the deep south of the US for $2,450

- ca. 2004. Bought for $14,000 by a scrap-metal dealer in the mid-west of the US

- 2014. Sold by this dealer to Wartski London and bought from them by an identified buyer for an undisclosed sum, estimated by market observers at about £20 million

Third Imperial Easter Egg by Fabergé Found! A Research Chronology compiled by Christel Ludewig McCanless, and published in Fabergé Research Newsletter, Summer 2014, summarized the history of the egg since 1887.

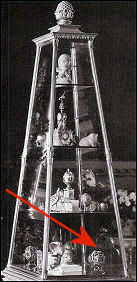

Maria Feodorovna Vitrine in von Dervis 1902 Exhibition with Egg and Its Reflection

(Archival Photographs)

THIS IS SPACE FILLER – SHH, DON’T TELL!

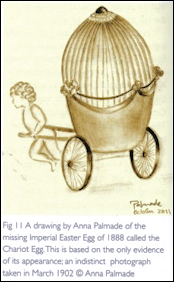

Anna Palmade Drawing and

Possible Prototype

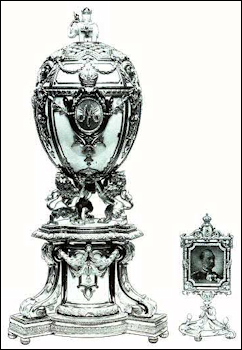

Cherub Egg with Chariot (1888)

(Munn, Geoffrey, “Unscrambled Eggs”, Antique Collecting (UK), June 2015, 44)

Tatiana Muntian, in her article in von Solodkoff, Fabergé: Juwelier des Zarenhofes (Hamburg, 1995) cites the inventories made in 1917 and 1922 of confiscated Imperial treasure. The 1917 list includes the following: “… gold egg, decorated with brilliants, a sapphire; with a silver, golded [sic] stand in the form of a two-wheeled wagon with a putto.” Muntian claims 1885 as the date the egg was made, but in the opinion of these authors, it must surely be the 1888 egg. It may be significant that neither of these descriptions mentions a clock.

- April 24 (OS), 1888. Would have been presented to Marie Feodorovna, a gift from Alexander III; cost 2,100 silver rubles

- March 1902 Shown in von Dervis exhibition (see illustrations above)

March 28 (OS), 1891. Housed at the Gatchina Palace - September 16-20 (OS), 1917. One of forty or so eggs sent to the Armoury Palace of the Kremlin in Moscow by the Kerensky Provisional Government for safekeeping

- February-March 1922. Transferred to the Sovnarkom, the Council of People’s Commissars

1930s. Possibly sold to Victor & Armand Hammer - September 26-27, 1941. Possibly part of lot 258 sold by Parke Bernet (New York) from the Collection of Mrs. Ethel Gunton Douglas of New York City, to an unknown buyer for $22.50 [sic]

- 2015. Whereabouts unknown

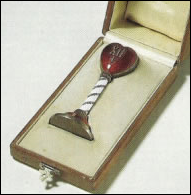

Pearl egg* – gold, rose-cut diamonds | Ring – gold, pearl

On page 3 of the file, dated February 22 (OS), 1889, a small egg-shaped leather case for the Easter egg is ordered, and on page 5, an account details one egg, one pearl 7.24/32 carats, five rose-cut diamonds, gold and double case, total cost 981 rubles, 20 kopeks. This figure of 981 rubles has been added in pencil to the bottom of the handwritten list of the Imperial Easter eggs from 1885 to 1890, made by N. Petrov, the assistant manager to the Cabinet of His Imperial Majesty. The list was found in the Russian State Historical Archives in St. Petersburg by Marina Lopato, and quoted in Apollo, January 1984 but these detailed descriptions do not agree with the invoice Fabergé sent to the Tsar on May 4 (OS), 1889, which details “1 Louis XV Nécessaire egg 1900 rubles”. (Fabergé, Proler, & Skurlov, Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs, London, 1997)

Tatiana Muntian says in von Solodkoff, Fabergé: Juwelier des Zarenhofes (Hamburg, 1995) that she found the following descriptions in the 1917 inventory of confiscated Imperial treasure: “gold egg/nécessaire, decorated with multi-colored stones and with brilliants, rubies, emeralds and sapphires.” Her fellow researcher, Valentin Skurlov, dated the egg at 1889, and the 1922 inventory of confiscated Imperial treasure concurs.

Tatiana Muntian says in her research published in von Solodkoff, Fabergé: Juwelier des Zarenhofes (Hamburg, 1995) the Resurrection Egg has no place in the list of Imperial Easter eggs presented by the Tsar. Her argument is convincing, especially in light of the Fabergé invoice, the inventory of confiscated Imperial treasure, and yet another description, noted when Marie Feodorovna took the egg from the Gatchina Palace to Moscow: “One item in the form of an egg, decorated with stones, containing ladies’ toilet articles, 13 pieces. Taken by the valet Ivoshkin when Their Majesties travelled to Moscow.” (Fabergé, Proler, & Skurlov, Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs, London, 1997)

This coincides almost precisely with the description of item number 20 in the Loan Exhibition of the Works of Carl Fabergé, which opened at Wartski London on November 8, 1949. Lent anonymously, the piece is described as “a Fine Gold Egg, richly set with diamonds, cabochon rubies, emeralds, a large colored diamond at top and a cabochon sapphire at point. The interior is designed as an Etui with thirteen gold and diamond set implements.” It would be the most extraordinary coincidence if these two eggs are not the same item, especially as Alexander III had stipulated there were to be no repetitions.

In March 2008, Kieran McCarthy of Wartski published material he had found in his employer’s files relating to lot 20 in the 1949 Wartski exhibition. The etui, which could well be the Nécessaire Egg, is partially shown on the bottom shelf of a display cabinet in a photograph taken at the exhibition. (Country Life, March 20, 2008, 60-61, excerpted in Fabergé Research Newsletter, The Missing Nécessaire Egg, April 2008 Anniversary Edition, and in Royal Russia, Annual no. 3, 2011, 92-93. McCarthy goes on to explain the item was lent anonymously for the exhibition and then in 1952 bought by Wartski’s who sold it the same year for £1200 to “a stranger.” McCarthy believes the purchaser was almost certainly British and that the current owners are unaware of its probable Imperial provenance.

There is as yet, no explanation regarding the original Pearl Egg*. The authors are of the view that the Pearl Egg, or the Pearl Egg pendant, as it is described by Fabergé, Proler, & Skurlov in Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs (London, 1997) was not the annual Easter gift from Alexander III to Marie Feodorovna. Apart from questions of dating arising with the Petrov list, Fabergé makes no mention of the egg pendant in his Easter bill to the Tsar. It seems possible initial plans were for the Pearl Egg to be the Easter gift, but that something happened which required the making of a second present, namely, the Nécessaire Egg. It should be noted both items were relatively inexpensive when compared with the cost of past and future Tsar Imperial Easter eggs.

- March 16 (OS), 1889. Pearl Egg presented to Alexander III at Gatchina Palace; cost 981 rubles, 20 copecks

- April 9 (OS), 1889. Nécessaire Egg would have been presented to Marie Fedorovna, a gift from Alexander III; cost 1,900 silver rubles

- March 28 (OS), 1891. Nécessaire Egg housed at the Gatchina Palace

- September 16-20 (OS), 1917. One of forty or so eggs sent to the Armoury Palace of the Kremlin in Moscow by the Kerensky Provisional Government for safekeeping

- February – March 1922. Transferred to the Sovnarkom, the Council of People’s Commissars

- Sold to a UK buyer

- June 19, 1949. Transferred from Wartski Llandudno, Wales, to Wartski, London, sold the same day to “a stranger” for £1,250

- 2015. Whereabouts of both eggs unknown; the Nécessaire Egg is possibly in a bank vault in the north of England

(Courtesy Hillwood Estate,

Museum and Gardens)

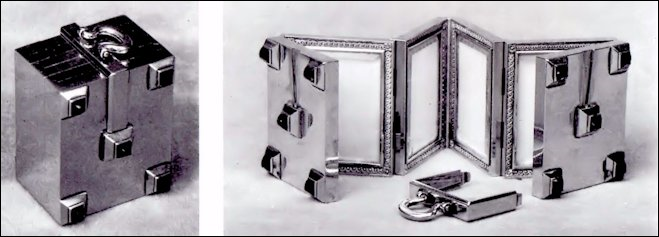

Missing Folding Miniature Frame Surprise Without Alexander III Miniatures by Zehngraf

(Snowman, A. Kenneth, Carl Fabergé, Goldsmith to the Imperial Court of Russia, 1979, 56)

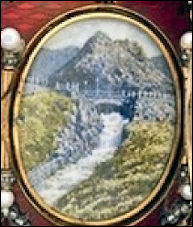

The egg opens to reveal a velvet lining for the missing surprise. Fabergé’s invoice describes the Egg: “Blue enamel egg, 6 portraits of H.I.M. Emperor Alexander III, with 10 sapphires and rose-cut diamonds and mounting. (Fabergé, Proler, & Skurlov, Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs, London, 1997) Christopher Forbes says the accompanying stand is modern. Another stand was made for the egg for the Russian Enamels: Kievan Rus to Fabergé exhibition in Baltimore, Maryland, November 17, 1996 – February 23, 1997.

This Egg is of relatively simple design, and may have been a deliberate calculation by Fabergé. The now Dowager Empress Marie Feodorovna was genuinely grief-stricken that her tall, immensely strong and determined husband, had died so young – he was 49. An elaborate memorial gift at this time would have only added to the young widow’s intense sorrow. Three more sophisticated memorial eggs to Alexander III would follow in future years.

Tatiana Muntian gives an insight into an incident involving the late arrival of the always much-anticipated Easter gifts: “In 1896, the Emperor – who was angry with the jeweler for he had delivered an Easter present late – in a letter to his mother who was in France, called him ‘foolish Fabergé’.” (Muntian, T.N., Fabergé Easter Gifts, Moscow, 2003) The Dowager Empress was attending her second son, George, in the south of France. Grand Duke George, suffering from tuberculosis, was staying at La Turbie, a picturesque village perched above Monte Carlo. Géza von Habsburg (Fabergé: Treasures of Imperial Russia, New York, 2004) expands on the incident, reporting the following exchange of letters between Nicholas II and Marie: “You will by post be receiving a little parcel – it is from me. That silly man Fabergé came too late to send it by courier.” From La Turbie, Marie replied:

Nicholas calmed down and, pleased with his mother’s response, he wrote back: “It was a great joy to me that you liked the egg – the miniatures of dear Papa are really successfully done and are good likenesses.” (Géza von Habsburg, in Fabergé: Treasures of Imperial Russia, New York, 2004). Two other eggs arrived late. In 1900, the Cockerel Egg was delivered to Marie’s Gatchina Palace outside St. Petersburg, when the Dowager Empress was in fact, in Moscow. And the 1909 egg was late arriving in London when Marie was staying at Buckingham Palace with her sister, Queen Alexandra.

There is no obvious reference to the Alexander III Portraits Egg in either the 1917 or 1922 inventories of confiscated Imperial treasure. Russian research indicates Alexandra Feodorovna actually helped pay for the cost of the egg. This was the only time she did this, and it was done before the two women became fully estranged. How the Egg found its way to the West remains unknown.

Fabergé researchers Anna and Vincent Palmade writing in the Fabergé Research Newsletter, Winter 2014, shared an exciting discovery – “1896 Alexander III Portraits Egg – Missing Surprise Identified in Photographs”. The frames, predictive of the ‘style moderne,’ were bought by Wartski for 420 guineas. Wartski images of the frames, which fold together into a neat ‘case’ with a handle above, are illustrated above. However, the portraits of the late Tsar in uniform had been removed, probably by the family before the item was offered at auction. The frames holding the miniatures are listed in the 1935 Belgrave Square exhibition catalog as being by Fabergé. Johannes Zehngraf, coincidentally, painted the miniatures for the Egg with Revolving Miniatures made in this year for Alexandra Feodorovna. Fabergé enthusiasts are searching for six miniatures (ca. 1.5 in. high x 1 in. wide) by Johannes Zehngraf of the ‘Emperor Alexander III in different uniforms’ which fit the folding frame surprise.

The Hillwood Museum staff tested a replica of the surprise inside the Alexander III Portraits Egg. The replica ‘chain’ of portrait miniatures was made using the dimensions and illustrations of the surprise. They fitted inside the egg so perfectly that they could barely move within their confines. The four top corners of the folded screen matched exactly the four marks on the velvet inside the upper part of the Egg. A news release (April 15, 2014) by the museum announced the re-dating to the egg which is now illustrated on the Hillwood Museum website in never-before-seen photographs.

- After March 24 (OS), 1896. Would have been presented to Marie Feodorovna, a gift from Nicholas II; cost 3,575 silver rubles. Housed in the Anichkov Palace. Probably sold to a Paris-based jeweler by Russian officials owned by Mrs. Andrea Bell Berchielly, Italy

- June 14, 1949. Bought by Marjorie Merriweather Post, General Foods heiress, as Mrs. Joseph E. Davies, from Mrs. Berchielly for the equivalent of $1739.13

- 1958. Owned by Mrs. Post as Mrs. Herbert May

- September 12, 1973. Collection of the late Marjorie Merriweather Post, at Hillwood Estates, Museum, and Gardens Washington (DC)

CLICK THESE IMAGES FOR LARGER VIEWS

1897 Mauve Egg Surprise (3¼ in., 8.3 cm.)

(Forbes, Christopher, and Robyn Tromeur-Brenner,

Fabergé: The Forbes Collection, 1999, 42-45)

THIS IS

SPACE FILLER – SHH, DON’T TELL!

1896 Fabergé Miniature

(4½ in., 11.5 cm.) in a

1997 Stockholm Exhibition

Mauve Egg with 3 Miniatures

(1897)

(Welander-Berggren, Elsebeth,

Carl Fabergé: Goldsmith to the Tsar, 1997, 161,

Photographs © Erik Cornelius, Nationalmuseum Stockholm)

The surprise was a heart-shaped frame. There is a strong suggestion that it may be the heart-shaped frame of strawberry enamel on a guilloché field formerly in the Forbes Magazine Collection and now in Viktor Vekselberg’s Link of Times Collection located in the Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg. It is set with the date 1897 in rose-cut diamonds and opens as a three-leaf clover with each leaf holding a rose diamond-encircled photograph: Nicholas II, Alexandra Feodorovna, and their firstborn, Grand Duchess Olga. The stem is of opaque, white enamel laurel leaves, and the base is of strawberry enamel, with circles of rose-cut diamonds and decorated with pearls. A spring mechanism in the shaft is triggered by pushing the central pearl in the base, which causes the trefoil of miniatures to snap shut, leaving only the heart displayed.

It is difficult to believe that Fabergé would have ignored such a major event as the arrival of the firstborn child of a ruling Tsar, with its implications for the Romanov dynasty and the nation as a whole. The Imperial family was no doubt hoping for a boy, following Tsar Paul’s edict after the death of his mother, Catherine the Great, that no female could in future inherit the throne. While probably personally disappointed the child was a girl, the Imperial family nevertheless rejoiced in her safe arrival on November 3, 1895 (OS). The Tsar recorded in his diary: “At exactly 9 we heard a child’s squeak, and we all breathed freely! A daughter sent by God, in prayer we named her Olga.” Seventeen months later, on March 7 (OS), 1897, the Dowager Empress Marie wrote to her father, King Christian IX: “Nicky’s [daughter] is an exceptionally large baby, unbelievably sturdy and fat and so heavy that one can really hardly carry her.”

Fabergé, Proler, & Skurlov in Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs (London, 1997) correct the amount paid by the Tsar for this egg from 3,500 silver rubles to 3,250 silver rubles. There is no mention of this egg in either the 1917 or 1922 inventories of confiscated Imperial treasure. This suggests the egg had been removed before 1917, perhaps by Marie Feodorovna herself, or, if displayed in the Gatchina Palace, destroyed by vandals.

There is a possibility this may be the “Easter Egg; miniature of the Empress Alexandra and the Grand Duchess Olga inserted. Lent by H.I.H. the Grand Duchess Xenia of Russia, Windsor (Editor’s note: Xenia was a sister of Tsar Nicholas II).” This brief description appears for item no. 563 in the catalog of the Exhibition of Russian Art at Belgrave Square in London in June 1935. The description does not mention the third miniature, namely, Nicholas II, and the Olga mentioned could be Xenia’s sister Olga Alexandrovna, not her niece. The egg is included under the exhibition heading: “Ornaments by Fabergé.”

Fabergé researcher Annemiek Wintraecken in the article, “1897 Mauve Egg Surprise” in the Fabergé Research Newsletter, Summer 2014, questions the long-held belief that the frame (first two illustrations above) is indeed the surprise for the 1897 Mauve Egg. She “wonders if the strawberry red or scarlet color of the frame really blends with the mauve enamel Egg description, and if the suggested surprise frame is indeed part of the lost egg”, and even more puzzling is, “Would Fabergé have repeated a similar design concept in a smaller version (last two illustrations above) for the Mauve Egg presented to the Empress in 1897?”

- April 13 (OS), 1897. Would have been presented to Marie Feodorovna, a gift from Nicholas II; cost 3,250 silver rubles, possibly sold to a UK buyer

- 2015. Whereabouts unknown

Possible Heart Surprise

- 1962. Lady Lydia Deterding, Paris

- April 26, 1978. Lot 381 sold by Christie’s Geneva to the Forbes Magazine Collection, New York, for SFr 40,000; £11,019

- February 2004. Sold privately as part of the Forbes Magazine Collection, New York, to Viktor Vekselberg, Moscow, for an undisclosed sum

- 2015. Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

The second is Fabergé’s bill to the Imperial Cabinet, which reads: “Egg in ‘Empire’ style, of nephrite with gold, two diamonds and miniature. (von Solodkoff, Fabergé: Juwelier des Zarenhofes, Hamburg, 1995) and a “nephrite egg with rose-cut diamonds” is mentioned in the 1922 inventory of confiscated Imperial treasure.

It is possible this is one of two Fabergé eggs referred to by Alexander Mosyakin in an article, “The Sale: Our Country’s Great Loss,” in the Moscow newspaper Ogonyok, No. 7, February 1989. Mosyakin says two eggs “of jadeite with dozens of brilliants” were sold for $450 each. This description might also fit the Diamond Trellis Egg. It is assumed the two previous descriptions of the Alexander III Medallion Egg omit certain elements because of their brevity. The newspaper description is also suspect because an object with “dozens of brilliants” would most certainly be worth more than $450, even in the 1920s or 1930s. Entry 553 for the Exhibition of Russian Art held in Belgrave Square, London, in June 1935 reads: “The Emperor Alexander III. Miniature by Zehngraf, in nephrite frame. Lent by H.I.H. the grand Duchess Xenia of Russia, Windsor.”

Was this the surprise from the now lost 1902 Alexander III Medallion Egg? The frame is by Fabergé. Johannes Zehngraf specialized in miniature portraits of the royal families of Europe. His work appears in the 1896 Egg with Revolving Miniatures, the 1898 Pelican Egg, and the 1898 Lilies of the Valley Egg.

- April 14 (OS), 1902. Would have been presented to Marie Feodorovna, a gift from Nicholas II; cost 6,000 rubles. Probably housed in the Anichkov Palace

- September 16-20 (OS), 1917. One of forty or so eggs sent to the Armoury Palace of the Kremlin in Moscow by the Kerensky Provisional Government for safekeeping

- February-March 1922. Probably transferred to the Sovnarkom, the Council of People’s Commissars

- 2015. Whereabouts unknown

(Courtesy Tatiana Fabergé)

Fabergé, Proler, & Skurlov say the Dowager Empress Marie was in her native Denmark at Easter, 1903. Her son, Tsar Nicholas II wrote to her: “I am sending you a Fabergé Easter present. I hope it will arrive safely. There are no secrets in it-the egg simply opens from the top.” Marie must have brought the Egg back to Russia on her return from Denmark because in July 1917, as German troops advanced towards Gatchina Palace, a list of treasures it contained was compiled before being evacuated to safety. Details of this inventory are given by Preben Ulstrup in Russian Empresses’ Mode and Style (2013). Item three is described as “Egg with blue and white enamel, in a gold mount, on columns of lions, an elephant on the top; in the middle, a portrait of the King and Queen of Denmark, decorated with precious stones.” In charge of these valuables was court official, Alexander Polovtsov. See the entry for the 1901 Gatchina Palace Egg for details about him and his later dealings with Fabergé eggs. Both the 1901 Gatchina Palace Egg and the 1907 Rose Trellis Egg were sold through him in Paris in the early 1920s.

Two quite opposite themes appear to have dominated Fabergé’s thinking when it came to Easter eggs for the dowager empressat the beginning of the twentieth century. The gifts were likely to be either family-related pieces such as this egg, the 1902 Empire Nephrite Egg, the 1909 Alexander III Commemorative Egg, and the 1910 Alexander III Equestrian Egg, or luxurious flights of fantasy, such as the 1906 Swan Egg, the 1908 Peacock Egg, and the 1911 Bay Tree Egg.”

- April 6 (OS), 1903. Would have been presented to Marie Feodorovna, a gift from Nicholas II; cost 7,535 rubles.

- For some time, possibly housed at the Anichkov Palace

- 2015. Whereabouts unknown

(Courtesy Tatiana Fabergé)

The Alexander III Commemorative Egg – like Marie’s 1896 and 1900 presents – was late reaching the Dowager Empress, who was visiting her sister, Queen Alexandra, in London. On March 26 (OS), 1909, Nicholas wrote to his mother “I am very sorry that I can’t send you an Easter egg today, but unfortunately Fabergé has not managed to have it finished, and I will send it to you in a week’s time. I ask you to forgive this involuntary lack of precision.” (von Habsburg, Fabergé: Treasures of Imperial Russia, New York, 2004). Presumably the egg reached Marie Feodorovna in England, before she set off for a Mediterranean cruise with King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra.

The egg has been out of public view since before the October Revolution of 1917. It does not seem to appear in either the 1917 or 1922 inventories of confiscated Imperial treasure. See the 1903 Royal Danish Egg for comments on what may have happened to it.

- After March 29 (OS), 1909. Would have been presented Marie Feodorovna, a gift from Nicholas II; cost 11,200 rubles. Apparently housed in the Anichkov Palace

- 2015. Whereabouts unknown

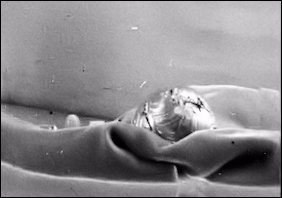

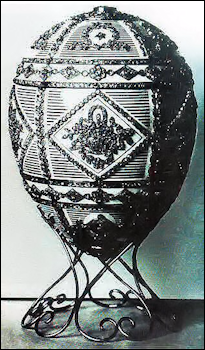

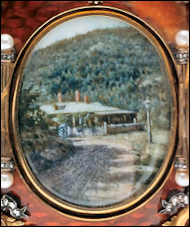

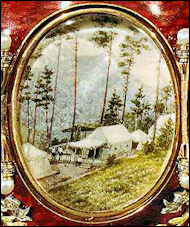

Caucasus Egg

(Keefe, Masterpieces of Faberge: The Matilda

Gray Foundation Collection, 2008, 84)

“1” House

(Keefe, Masterworks of Fabergé:

The Matilda Geddings Gray

Foundation Collection, 2008, 82)

“9” Tents

“3” House

(Keefe, Masterpieces of Fabergé:

The Matilda Geddings Gray Foundation Collection, 1993, 130)

“Sweet Meat Box” Egg

(Courtesy Christie’s)

1887 Third Imperial Egg

(Courtesy Wartski)

(Updates are posted in Exhibitions on the Fabergé Research Site)

Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

The Fabergé Museum Advisory Board met for their annual meeting on 4-5 June 2015. During their sessions, they addressed the main questions relating to the first Fabergé Museum conference of 2015. Board members supported the initiative to regularly hold international scientific forums in the museum and confirmed they would be taking part. The conference agenda was reviewed by the experts, a list of well-known presenters was added, and suggestions were made regarding the exhibition program for the time of the conference. During the meeting, it was suggested the conference name be changed to: The First International Fabergé Museum Conference: Lapidary Art.

The conference’s organizing committee has put forth the following topics for discussion:

- The Fabergé Museum’s collection of lapidary art.

- The mineralogy production of House Fabergé and its contemporaries.

- The restoration and conservation of lapidary art.

- Problems of attribution and expertise in lapidary art.

- Russian lapidary art in the context of foreign and Russian art traditions.

- Collecting lapidary art.

- Fabergé’s heritage in modern lapidary art practices.

- Primary trends and potential development of modern lapidary art.

The list of presenters for the conference already includes such well-known international experts as Géza von Habsburg, Alexander von Solodkoff, Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm, Valentin Skurloff, Maxim Artsinovich, Lyudmila Budrina, Caroline de Guitaut, Patrick Dreher, and Fabian Schmidt.

Conference Organizing Committee, +7 812 600 11 44

www.fabergemuseum.ru, conference@fabergemuseum.ru

Fabergé Museum, Shuvalov Palace – Fontanka River Embankment, 21

191023, St. Petersburg, Russia

Viktor Aarne (Active 1880-1904) Lötz Glass Lamp,

Tiffany Favrile Glass Scent Flask and Vase All with Silver Mounts by Fabergé

(Archival Photograph, Courtesy McFerrin Collection)

On March 31, 2015, the Schatzkammer (Treasure Chamber) opened in Vaduz, the capital city of Liechtenstein. The new museum’s focus is primarily on exhibits belonging to the Princes of Liechtenstein and other private collectors. The first venue (last entry on the German newscast) includes hundreds of Russian Easter eggs and the Kelch Apple Blossom Egg by Fabergé donated in 2010 by Liechtenstein collector Adulf Peter Goop (1921-2011). The 1998 catalogue raisonné, Kostbare Ostereier aus dem Zarenreich: Aus der Sammlung Adulf Peter Goop (Priceless Easter Eggs from the Treasures of the Tsars: From the Collection of Adulf Peter Goop), discusses their history and symbolism, and illustrates lacquered, porcelain, glass, silver, cloisonné, and Fabergé eggs. The Kelch Egg is on permanent display. (Courtesy Jürg Spühler; Royal Russia News)

Introduction by Christel McCanless: In 1994 I attended the Fabergé Winter Egg auction in Geneva. In my free time I visited the Olympic Museum and to my delight discovered two Fabergé trophies. Twenty years later I found the sketches I had made at the time and after a few emails with Claire Sanjuan, Public Relations Manager at the museum, I am delighted to publish the historical research shared by the Collections Department Staff of the Olympic Museum. Carl Fabergé fled St. Petersburg in 1918 as a Foreign Embassy Courier, settled in Lausanne, where he died on September 24, 1920. His ashes were moved in 1929 by his son Eugène Fabergé to Cannes, France, for burial in the grave of Madame Fabergé (1852-1925).

José Antonio Ardanza Garrodu, President of the Basque Country, and Juan Antonio Samaranch, 7th President of the International Olympic Committee (IOC)

viewing the Fabergé Kovsh at the Olympic Museum, March 16, 1994.

(Photographs ©IOC/Jean-Jacques Strahm)

(Ed. note: The above 1912 decathlon trophy is also illustrated in Welander-Berggren, Elsebeth, Carl Fabergé: Goldsmith to the Tsar, 1997, 229, and the suggestion is made an accompanying Fabergé drawing is the model for the Olympic Museum trophy. However, the drawing held by the State Hermitage Museum matches more closely the Monumental Bogatyr Kovsh, formerly in the Forbes Magazine Collection illustrated in von Habsburg and Lopato, Fabergé Imperial Jeweller, 1993, 347 and 415.)

Like all challenges trophies, the Fabergé cup was to be returned for the 1916 Olympic Games. However, these Games were not held because of the First World War and it was therefore not awarded. At the 1920 Olympic Games in Antwerp, Belgium, the decathlon event was won by Helge Andreas Loevland from Norway. In the Official Report of these Games, it is stated that the International Olympic Committee (IOC) decided not to transmit challenges trophies anymore, since they were too precious and fragile to travel. The name of the winners should therefore be written on a plaque displayed above the trophies in the Olympic Museum in Lausanne. According to our sources, it is thus possible Loevland never “physically” received the challenge trophy.

In the early years of the Modern Olympic Games (1908-1920), Olympic challenge cups or trophies were created in order to be awarded to a specific discipline or event. They were provided by prominent persons and presented to gold medallists on a temporary basis. At the 22nd IOC session held in Rome in 1923 the Committee discontinued the practice of awarding challenge trophies and most of them were delivered to the Olympic Museum in Lausanne, which now owns an almost complete collection. The Fabergé trophy is on display in the museum’s permanent exhibition. You may notice that one of the oars is slightly different and is probably not original. We have no record of a prior restoration, but one may imagine damage occurred during the transport.

Fabergé Trotting Horse Breeding Trophy Presented in ca. 1989 by

Attorney and Collector Pierre Sciclounoff to Juan Antonio Samaranch,

President of the IOC from 1980-2001

(Photographs ©IOC/Michèle Verdier)

Additional sources on the Olympic challenges trophies:

- London 1908 Official Report, pp. 27, 44-45, 655.

- Stockholm 1912 Official Report, pp. 94, 164-165, 784 (Part 1 & Part 2).

- Antwerp 1920 Official Report, p. 81.

- Lennartz, Karl, Olympische Siege: Medaillen, Diplome, Ehrungen, 2000, 146-158.

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Virginia

Under the leadership of Ms. Lee Bagby Viverette, Director of Library, Archives and Special Collections at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) awarded a planning grant related to digitizing the archival materials well as the curatorial and conservation files related to the 1947 Pratt donation. With an additional grant by the Washington Art Library Resources Committee (WALRC), both grants are administered and supported through the museum’s Artshare Initiative.

Ed. note: The year is now 2015 and Mr. Viktor Vekselberg, the founder of the Fabergé Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia, recently received The Art Newspaper Russia Prize for His Personal Contributions. The Link of Times Collection contains 1,500 Fabergé and objects and is housed in the restored Shuvalov Palace on the Fontana Embankment.

Grand Duchess Marie Georgievna, neé Princess Marie of Greece and Denmark, was the second daughter of King George I of the Hellenes and Queen Olga Konstantinovna, who was born a Romanov grand duchess. She married Grand Duke George Mikhailovich (1863-1919), the third son of Grand Duke Mikhail Nikolaevich, on the Greek island of Corfu in 1900. The couple had two children: Princess Nina and Princess Xenia. The grand ducal couple initially lived at Mikhailovskoe, the Baltic coast home of Grand Duke Mikhail Nikolaevich, and then subsequently moved into apartments of the Novo Mikhailovsky Palace in St. Petersburg. The family eventually relocated to their newly-built estate, Harax (Kharaks), in the Crimea.

The marriage was not a happy one and as the years passed, the couple spent more time apart. Grand Duchess Marie Georgievna and her daughters traveled to England in July 1914 just prior to the start of World War I. According to her memoirs, Marie took her daughter Xenia specifically to Harrogate for the “bracing air” on the advice of her daughter’s physician due to Xenia’s weight loss and intolerance of the hot climate1. Once war erupted, the Grand Duchess and her daughters never returned to Russia due to the instability of war-torn Europe. The Grand Duchess spent the war years nursing and organizing a number of hospitals for wounded soldiers in Harrogate, England2. Fortuitously, Marie and her daughters were spared imprisonment and death during the Russian Revolution by not returning to home; however, they did not escape tragedy entirely. Grand Duke George Mikhailovich was executed by the Bolsheviks in 1919, along with other members of the Romanov dynasty.

In her memoirs, the Grand Duchess describes her life as a member of the Russian Imperial family, but unfortunately she only devotes one paragraph to the 1913 Romanov Tercentenary celebrations, with no mention of the Fabergé presentation gifts3. The three Fabergé plates possibly left Russia when Grand Duchess Marie and her daughters left for England in 1914, or were possibly removed in 1919 by members of the Romanov dynasty who fled the Crimea aboard the British warship HMS Marlborough. The Dowager Empress Marie Feodorovna had been living in Grand Duchess Marie’s home, Harax, prior to being evacuated from the Crimea4. After being exiled from Russia and financially ruined by the collapse of the Tsarist government, Grand Duchess Marie rebuilt her life and married Pericles Ioannides, a Greek admiral, in 1922. Unfortunately, she would also endure the changing fortunes of the Greek Royal family, when they were exiled due to political unrest and then invited to return to Greece. Marie died in her beloved Greece in 1940. Princess Nina married Paul Alexandrovich Chavchavadze, a direct descendent of the last king of Georgia. Princess Xenia was first married to millionaire William Bateman Leeds and then to Herman Jud. Both daughters eventually emigrated to the United States.

Grand Duchess Marie

Georgievna with Daughters

Xenia and Nina

(Courtesy Alexander Palace

Time Machine)

Marie Georgievna Romanov

Tercentenary Plate

(Odom, What Became of Peter’s Dream?

p. 87, Item 15)

Xenia Georgievna Romanov Plate

(Both Plates Courtesy of Middlebury

College Museum of Art)

Nina Georgievna Romanov Plate

(Courtesy Christie’s New York)

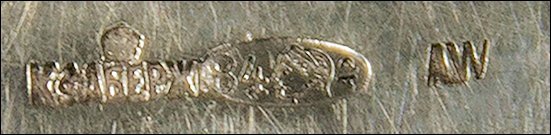

In considering the inconsistency between the workmasters’ hallmarks, it seemed most likely that all three items would have been made in the same workshop given their near identical design and presentation inscription. To solve the question of the hallmarks, Mark Moehrke, Vice President and Head of Christie’s Russian Works of Art Department, Dr. Emmie Donadio, Chief Curator of Middlebury College Museum of Art, and Margaret Wallace, Museum Registrar for Middlebury College Museum of Art, provided invaluable assistance by sharing hallmark illustrations for the three plates. The photographs made it possible to confirm the plates all have the ![]() mark used by Fabergé workmaster Alexander Väkevä (1870-1957), son of Stefan Väkevä, a Finnish silver master, who founded his St. Petersburg workshop in 1865. According to research shared by Fabergé scholar Dr. Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm, who has studied Fabergé’s workmasters extensively, Stefan was a member of the St. Maria Lutheran congregation in St. Petersburg, where the spelling of his name was altered in the German language church records. The “V” became a “W” to mimic the same sound in the German language, since the “V” in German has an “F” sound. Ordinarily, the family continued to use the regular spelling of their name: Väkevä. According to descendants of the family, the “W” version sounded more exotic to the Finnish ear, so Stefan incorporated it into his hallmark which was later replicated in his children’s hallmarks as well. Alexander apprenticed under his father and qualified as a master silversmith in his own right. The Väkevä family workshop produced silver items for the House of Fabergé under an exclusive contract from the late 1870’s. From 1910 to the revolution, Alexander managed the workshop after the death of his father.

mark used by Fabergé workmaster Alexander Väkevä (1870-1957), son of Stefan Väkevä, a Finnish silver master, who founded his St. Petersburg workshop in 1865. According to research shared by Fabergé scholar Dr. Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm, who has studied Fabergé’s workmasters extensively, Stefan was a member of the St. Maria Lutheran congregation in St. Petersburg, where the spelling of his name was altered in the German language church records. The “V” became a “W” to mimic the same sound in the German language, since the “V” in German has an “F” sound. Ordinarily, the family continued to use the regular spelling of their name: Väkevä. According to descendants of the family, the “W” version sounded more exotic to the Finnish ear, so Stefan incorporated it into his hallmark which was later replicated in his children’s hallmarks as well. Alexander apprenticed under his father and qualified as a master silversmith in his own right. The Väkevä family workshop produced silver items for the House of Fabergé under an exclusive contract from the late 1870’s. From 1910 to the revolution, Alexander managed the workshop after the death of his father.

Marks on Marie’s 1913 Plate

(Courtesy Middlebury College Museum of Art)

Marks on Xenia’s 1913 Plate

(Courtesy Middlebury College Museum of Art)

Marks on Nina’s 1913 Plate

(Courtesy Christie’s New York)

Although these three plates are considered very plain when compared with much of Fabergé’s more ornate work, they commemorate one of the most important moments in Imperial Russian history, the Romanov Tercentenary. My research project has confirmed through photographic evidence that these three plates were made in the workshop of Alexander Väkevä, a lesser-known Fabergé workmaster. It is exciting to find a Fabergé item with an Imperial provenance complimenting known Romanov heirlooms in the Middlebury College Collection, and to discover Princess Nina’s plate actually exists and was not melted down, or lost during the Russian Revolution. Perhaps ongoing research will reveal, if Grand Duke George Mikhailovich received one as well.

1A Romanov Diary: The Autobiography of H.I. & H.R. Grand Duchess George of Russia, 1988, 157.

2Hall, Coryne. Princesses on the Wards: Royal Women in Nursing through Wars and Revolutions, 2014, 131-140.

3A Romanov Diary, 146.

4Robinson, Paul. Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich: Supreme Commander of the Russian Army, 2014, 308.

5Odom, Anne. What Became of Peter’s Dream? Court Culture in the Reign of Nicholas II, 2003, 87, item 15.

6von Habsburg, Géza, von Solodkoff, Alexander, and Robert S. Bianchi. Fabergé: Imperial Craftsman and His World, 2000, 404-406.

Where Are the Fabergé Objects Now?

Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich and His Family in 1899

(Courtesy Liki Rossii, St. Petersburg)

In the 1899 NYH article the reporter mentioned 36 golden plates forming the most magnificent service one could imagine “of the most simple and at the same time artistic design, bearing the imperial arms surrounded by a border in pure Empire style. On the back of each plate is written in full the name of the donor”. We discovered the plates were made by Carl Fabergé2, and they were given to the couple as a joint gift from Grand Dukes and Grand Duchesses. In Grand Duke Georgy Mikhailovich Fund it is written he paid 68 rubles (1/36 of the full price) to Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich who paid the jeweler Fabergé 2448 rubles for the set. Of course, we dream of finding in a museum or in a private collection one of these plates with the name of a donor.

Another piece by Fabergé presented to the grand ducal couple was “a vase, both touching and beautiful”. It was given by Vladimir Bock, an assistant to the Superintendent of the Hermitage, and son of the Hofmeister to Grand Duke Vladimir. Thanks to our research we can confirm the mounting for this item was also made by the Fabergé firm.3

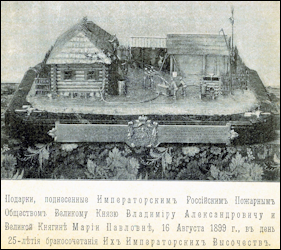

The most interesting and intricate presents were given to Grand Duchess and Grand Duke by members of the Imperial Russian Firefighters Society. In the NYH newspaper a present to Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich is described eloquently:

Large Smoker’s Compendium Given to

Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich

as an Anniversary Present

Russian Izba (4) Smoker’s Compendium by Fabergé,

Length 14 5/8 in., 37.2 cm

(Forbes, Christopher, and Robyn Tromeur-Brenner,

Fabergé: The Forbes Collection, 1999, 246-7)

Fabergé Silver Fire Composition

Presented to Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna

by the Imperial Russian Firefighters Society

(Illustration #1 and #3: Pozharnoye Delo Magazine, 1899 (5), Courtesy: Russian National Library, St. Petersburg)

In another contemporary Russian magazine article we discovered that the Imperial Russian Firefighters Society also gave a present to Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna. Additional images and detailed descriptions of both gifts for the anniversary couple surfaced, but unfortunately, the workmasters were not mentioned. Maria Pavlovna’s gift is described in the Pozharnoye Delo Magazine, yet it is not mentioned in NYH. The gift has a cupid holding in his left hand a map of Russia on which is depicted the route of the traveling Firemen Exhibition for three years. In his right hand, the cupid is holding a fireman’s helmet. Behind him is a porte-bouquet to which on the day of the silver wedding anniversary a beautiful bouquet of red roses was added. On the marble pedestal a coat-of-arm of the recipient is the inscription “IRPO (Imperial Russian Pozharnoye (Firemen) Obshchestvo (Society) to Her Imperial Highness Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna, August Patron of All Russia Travelling Exhibition.” The authors suggest a comparison of the two IRPO presents, the inscriptions, as well as the style and detail of workmanship allow us to affirm they were created by Fabergé. Where are the four gifts now?

Fabergé Cigarette Case with “XXV”

for the Vladimirs 25th Wedding Anniversary,

When Turned 180 Degrees Their Initials

“W” and “M” Appear.

(Courtesy McFerrin Collection)

Maria Pavlovna photograph was the model for an Imperial presentation pendant with miniatures of Vladimir and Maria.

The authors are searching for more archival details for this pin.

(Wiki, Courtesy McFerrin Collection)

1Korneva, Galina, and Tatiana Cheboksarova, Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna, 2014. Two editions published by Liki Rossii in St. Petersburg, and Eurohistory, respectively.

2RGIA, Fund 350, Inventory 1, File 256, p. 89.

3GARF, F. 655. Inv.1, File 1105. Letters to Grand Duchess Marie Pavlovna.

4Izba, a traditional Russian farm house built without nails and saws, but using simple tools, such as ropes, axes, knives, and spades during construction.

5Pozharnoye Delo Magazine, 1899, #9, 594-595.

6RGIA, Fond 526, Inv. 1, file 307, p. 43.

7RGIA, F. 526, inventory 1, file 539, p. 119, opposite side.