Fabergé Thimbles

by Magdalena and William Isbister

The Fabergé family fled France when the Edict of Nantes was revoked in 1685. They settled in Estonia (formerly known as Livonia) and in 1842 Gustav Fabergé went to live in St. Petersburg and became one of the town’s most famous jewelers. His son Carl was born in 1846 and was educated at home in St. Petersburg as well as in Germany, Italy, England, and France. Carl Fabergé returned to St. Petersburg in 1870 to take over his father’s business and in so doing he changed the emphasis of the atelier’s work and started to produce objects of sheer fantasy. Were any of these objects thimbles? This question is often asked by thimble collectors who wonder whether the House of Fabergé or any of its workmasters ever made such a piece. As we will see, there is much confusion in the thimble literature regarding the answer to this question and in this paper we will explore the subject of ‘Fabergé’ thimbles in detail and try to arrive at the definitive answer.

A search in Lowes and McCanless Index to Fabergé at Auction (1) provided us with a list of ‘Fabergé’ thimbles auctioned between 1932 and 2005. In addition, we examined the archival databases maintained on the web by the two major auction houses, Christie’s and Sotheby’s, from the early 1990′ s to the present, but this did not yield any new lots. The thimbles found in our searches will be described in the paper.

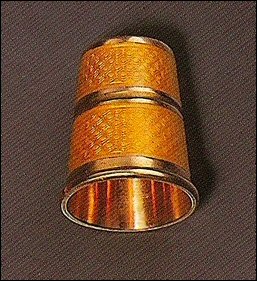

The Fabergé thimble story seems to abound with ‘fakes’, ‘hybrid thimbles’ purporting to be from the Fabergé workshops, and controversy. A. Kenneth Snowman, grandson of Morris Wartski, son of Emanuel Snowman and chairman of the Wartski Company in 1977, is on record as saying that he had never come across a Fabergé thimble (2). The significance of this statement can be understood when it is remembered that Emanuel Snowman was one of the first people to negotiate with the government of the Soviet Union to purchase treasures that had been confiscated following the revolution of 1917. Wartski, now based in London, has specialized in fine jewellery, gold boxes, silver and works of art by Fabergé since that time. In Thimbles (3) Holmes wrote “The splendours of Russian enamel evoke the name of Fabergé but so far as can be determined no Fabergé thimble was ever made.” Von Hoelle (4) on the other hand states that Carl Fabergé was “the famed master jeweler of the Russian Czars who was known to have made thimbles, six of which are known to be in private collections. One was sold at Christie’s in Geneva on Nov. 13, 1985, for $4,500.00. It was two-toned gold with guilloche enamel on the side, signed with the initials of Michael Perchin, a workmaster of Fabergé, and dated about 1880.” (lot 20, 13.11.85) (fig 1). It was bought by the Forbes Magazine Collection. Holmes (2) questioned the authenticity of this thimble and pointed out that Perchin only worked for Fabergé from 1886 on-wards.

Fig 1 © Christie’s

The Forbes thimble was not the first Fabergé thimble to come up for auction. In 1981 Christie’s in Geneva (lot 32, 17.11.81) auctioned a gem-set gold thimble with tapering engine turned sides applied with scrolls. The agate top was circled by rose cut diamonds and according to the auction catalogue the thimble was made in St. Petersburg in the late 19th century and attributed to Michael Perchin (M.П or M•П). Holmes seems to have been reasonably convinced that this thimble was a genuine Fabergé thimble (5).

In A History of Thimbles (6), Holmes’ second book, he wrote ‘the splendour of Russian enamel recalls the name of Fabergé, but genuine Fabergé thimbles are extremely rare. Only two or three authentic examples are known, including one made by Henrik Wigström (H.W.), who headed Perchin’s shop when Perchin died in 1903 and who from that date assumed responsibility for making the imperial eggs.’ Holmes had clearly changed his mind.

Dreesmann in A Thimble Full, published in 1983, describes her quest for a Fabergé thimble, which led her to the collection of Mrs George Mitchell (7). She failed to secure the thimble she wanted but did photograph two ‘Fabergé’ thimbles in the Mitchell Collection.

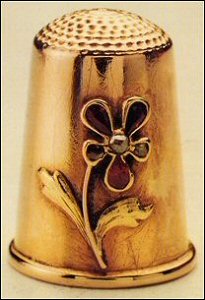

Fig 2

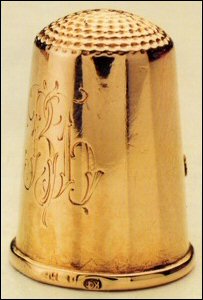

Fig 3

The thimble in figure 2 has a red enamel and flower decoration around the rim and a white agate stone top. The thimble was machine dimpled. The workmaster is said to be Henrik Wigström (7). The second thimble (fig 3) is of varicoloured gold with the sides decorated in pink enamel. It has a rather bulbous blue chalcedony stone top and clearly it might not be of much use for sewing. This thimble was attributed to Wigström too (7). Fabergé workmasters often ‘topped’ suitable items with cabochon stones. Nothing is known of the markings on these two thimbles.

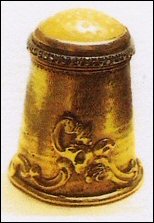

Fig 4

In 1983 A La Vieille Russie (ALVR) organised a loan exhibition of Fabergé pieces in New York (8) for the benefit of the Cooper-Hewitt Museum, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Design (fig 4). In addition to the two thimbles described above (fig 2, 3) there was a third thimble in the exhibition. It was a gold child’s thimble with a squarish cross section and it was decorated around the rim in a Greek key design in blue enamel. Although the marks were unclear, the exhibition catalogue said that it was made by the Fabergé workmaster Feodor Afanassiev (фA), a specialist in small objects. It was later auctioned by Sotheby’s in New York in 1992 (lot 484, 8.12.92). The exhibition was organised by Mr Peter Shaffer of ALVR of whom Holmes wrote (2) ‘it was he who was responsible for the A La Vieille Russie exhibition and he surely erred on that occasion.’ Holmes was writing of the thimbles exhibited and although no records exist now it is presumed that, at the time, Holmes felt that at least one and probably two of the thimbles illustrated in the catalogue had not been made by Fabergé, or one of his workmasters. Certainly the two thimbles with machine-dimpled sides could have been made by any of many of the European goldsmiths of the time, and the shape of the third thimble with the very narrow top makes it quite unlikely that it would have fitted over any finger unless it was very steeply tapered! These three ‘thimbles’ may either not have been made by the House of Fabergé, or one may not actually have been a thimble.

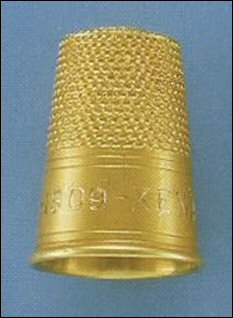

In Geneva in 1987, Christie’s auctioned a gold thimble (lot 152, 11.11.87), which was made by Henrik Wigström according to the auction catalogue (fig 5). The thimble was made of 14 carat gold and the wide matt border was engraved with the names “Nina – 1909 – Xenia – Xmas”. It was marked 56 and housed in an original fitted wooden Fabergé box.

Fig 5 © Christie’s

The thimble had belonged to Miss Annie Bell who was the nurse of the Princesses Nina and Xenia, daughters of the Grand Duke George and Grand Duchess Marie of Russia, and was a Christmas gift from the Princesses to Miss Bell.

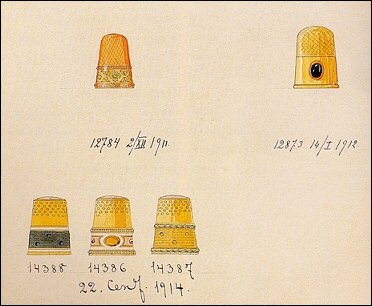

According to Holmes (5) the thimble was a plain unsophisticated thimble, made in two parts, with hand made dimpling. It was interesting in that not only did it have a robust provenance but also that the dimpling was far from perfect (9). This might be expected from a workshop where few thimbles were ever made and tends to confirm the absence of knurling wheels in the Fabergé workshops. The watercolour drawings in figure 11 seem to show this rather coarse dimpling that might have been made by hand. It follows that a machine-dimpled thimble would be unlikely to have been made by a Fabergé workmaster and thus, some of the doubt expressed by Holmes regarding the thimbles in the A La Vieille Russie exhibition may, at least in part, be justified.

In 1989 Holmes warned of two fake ‘Fabergé’ thimbles, which had been seen in London West End shop windows (10). One of these thimbles re-appeared in 1992 in the hands of a dealer. On this occasion the Fabergé mark had been scratched out and the thimble was simply offered as Russian (11). In September 1990 (lot 261, 11.9.90) what was probably a fake ‘Fabergé’ thimble went through Christie’s, it did not even merit an illustration in the auction catalogue (12), and another fake ‘Fabergé’ thimble complete with fake Fabergé presentation case was sold in the Portobello Market in 1992 (13).

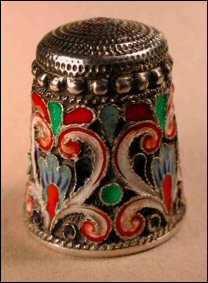

In the summer of 1992 a Russian enamel thimble (fig 6) was pictured on the cover of the TSL Magazine (14). The author suggested that it was ‘enamel on silver in the “old Russian style”. It bears the marks 84 (pre-revolution) the kokoshnik mark facing right, and the initials of Fabergé’s workmaster in the Odessa workshop, Carl Gustav Lindell’ (in Cyrillic). ‘These marks have been verified by expert dealers in Russian silver, and the style and quality of the enameling have been judged as genuine. The small amount of wear on the enamel, and the fading of the gilding have given added weight to the correct age estimation.’ Presumably the Carl Gustav Lindell referred to above must actually be the Finnish journeyman Karl Gustaf Johansson Lundell. He was not a master at Odessa because he never passed his master’s exam and could therefore not have had a mark of his own (15). The mark ‘гл‘, found on this thimble, is from an unknown master (15).

Fig 6

Holmes was not convinced about this thimble either (11). He thought that it was ‘poor of its kind’ and did ‘not look pre-revolutionary, let alone like the work of a prestigious jeweler.’ He thought that it looked like a post-revolution factory made specimen or else a reproduction. He argued that maker’s marks on pre-revolution thimbles are normally so badly imprinted that they are unidentifiable. Holmes felt that ‘there must be a strong suspicion verging on certainty’ that it was another fake mark. Although the marks on this thimble suggest that it was made between 1908 and 1917, the goldsmith-journeyman Karl Gustaf Lundell died in St. Petersburg on the 29.5.1856 at age 23 and Fabergé opened the Odessa workshop in 1890 (15). Clearly ‘Lindell’ could not possibly have made the thimble and, of course, Holmes was right because the information given about ‘Lindell’ in the TSL magazine was quite obviously incorrect.

There is no doubt that thimbles do exist that were not made by any Fabergé workmaster, but which bear a ‘Fabergé’ mark (fig 7, 8).

Fig 7

Fig 8

Thimbles with Fabergé workmaster’s marks also exist (Fig 9, 10) (16, 17) but the vast majority of these thimbles are fakes (18), as are the two thimbles illustrated here (fig 7, 9). The silver thimble with the three applied cabochon stones has the word Fabergé in Cyrillic and the correct pre-revolution mark (fig 8) but the thimble also has the German 800 mark and clearly the thimble was never made in Russia.

Fig 9

Fig 10

Figure 9 shows a ‘cast’ Russian enamel thimble. The enamel work is quite good and the marks inside the top are all correct for the supposed age and place of manufacture of the thimble (fig 10). The workmasters mark is supposed to be for Alfred Thielemann (AT), a Fabergé workmaster, working in St Petersburg, who never made cloisonné, shaded or champlevé enamel. His master’s mark would thus never have been associated with a Moscow town mark (George and the Dragon). The mark is not quite right either because there should not be a ‘period’ separating the letters. The thimble must be a fake and was never made by a Fabergé workmaster far less Alfred Thielemann. Original Fabergé punches seem to have been ‘removed’ to the west during the communist rule and now are freely used by fake thimble makers. The punch marks may thus be ‘original’ but the thimbles are most certainly not. Thimbles marked in this way have been described as original Fabergé thimbles.

In 1992 Dr Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm was fortunate enough to discover an album of drawings (19), which belonged to Fabergé workmaster, Henrik Wigström, who was a pupil and later a colleague of Michael Perchin in his St. Petersburg workshop. They both worked exclusively for the House of Fabergé, which employed several workmasters, scattered throughout the city in their own workshops, at any one time. These workmasters employed their own workers and were responsible for their own work. They were working independently but their output was for Fabergé. They were allowed to mark their pieces with their own marks and trained apprentices and employed journeymen. In 1900 the House of Fabergé brought the St. Petersburg workmasters together in one building where Fabergé himself had an apartment. Wigström and his family lived in the building also. This proved to be a very efficient way to run the business.

The Wigström album of watercolour drawings covers the period from 1911-1916 and details designs for the workshop’s output. Under the drawing of each thimble in the album is a production number and a completion date. It is thus possible to be sure that such designed pieces were actually made. The number in the album did not match the inventory number, which was scratched onto the piece when it was taken into stock in the Fabergé shop.

Fig 11 (Tillander-Godenhielm et al., Golden Years of Fabergé, 2000)

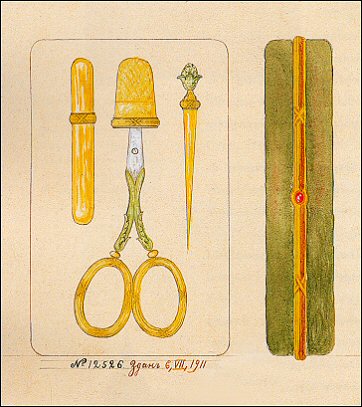

Plate 91 of the Wigström album of drawings (fig 11) shows five thimbles with completion dates, plate 195 of the album (fig 12) shows an etui with scissors, a needle case, a bodkin and a thimble and was completed in 1911.

Fig 12

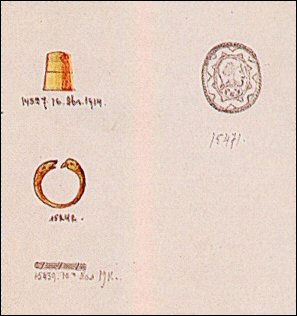

Fig 13

The seventh thimble is shown in plate 93 of the album (fig 13) and appears to have been completed in 1914.

The first definitive answer to the question regarding whether Fabergé ever produced thimbles is thus provided by the Wigström album of drawings. Despite what has been written before, by experts and non-experts in the thimble literature, there is now definitive evidence that Fabergé did make thimbles although the numbers seem to have been quite small. Henrik Wigström certainly completed seven thimbles and in all probability some of the other workmasters made thimbles too. The whereabouts of these thimbles is unknown and some have undoubtedly been lost. None of the thimbles pictured in Wigström’s album seem to correspond to any of the known thimbles so far attributed to Wigström.

Christie’s auctioned a gold needle case at their Geneva rooms in 1993 (lot 469, 25-26.5.93) (fig 14). It was cylindrical in shape and enameled all over in purple over a moiré ground. The top was hinged with a rim of chased gold leaves on a white enamel ground. There was a gold ring for suspension. The case contained a thimble with similar decoration and a gold double thread reel and needle case. According to the auction catalogue it was made by Henrik Wigström in St. Petersburg in 1906.

Fig 14 © Christie’s

In 1995, Christie’s auctioned another Fabergé thimble in Geneva (lot 381, 16-17.5.95) (fig 15).

Fig 15 © Christie’s

It was a gold and guilloché enamel thimble of tapering form with two bands of yellow enamel and a reeded border and in the auction catalogue was said to have been made between 1899 and 1903 by August Holmström (AH) in St. Petersburg. His son, Albert, was also a Fabergé workmaster and used the same mark. In 1986, A. Kenneth Snowman discovered two Holmström design books (20), which recorded in ‘richly illustrated detail all the business conducted by the Albert Holmström (AH) workshops from 6 March 1909 to 20 March 1915.’ The workshop of Albert Holmström was primarily a jewellery workshop and there were no designs for thimbles in the stock books. Together with the Wigström albums from 1911-1916, they constitute the only surviving documentary material produced by the Fabergé workshops themselves.

In the same year, and also in Geneva, Sotheby’s auctioned a ‘Fabergé’ two coloured gold and enamel thimble (lot 536, 13-15.11.95) (fig 16).

Fig 16

Fig 17

It had a brick red translucent enamel band above a chased laurel rim. In the auction catalogue it was said to have been made by Henrik Wigström in St. Petersburg in the late 19th century. Henrik Wigström only became a Fabergé workmaster in 1903 so clearly the catalogue description is less than accurate and we wonder whether the thimble is possibly not a Fabergé thimble either? A very similar 20th century French enamel thimble made by René Lorillon, a Parisian thimble maker, is shown for comparison (fig 17).

In 1997, a gold thimble (fig 18) which bore the Fabergé mark for small objects made in St Petersburg, appeared on the cover of the German thimble magazine, Rund um den Fingerhut (21).

Fig 18 © Rund um den Fingerhut

Fig 19 © Rund um den Fingerhut

The thimble had plain sides with an applied two gold flower with three diamond and three ruby petals. A Cyrillic monogram, ВБ (WB), was engraved on the opposite side of the thimble and the top was crudely dimpled. It had a plain round turnover rim. The rim was marked (fig 19) 56 and KF in Cyrillic (Kф). The maker’s mark was rubbed.

We found a further picture of a Fabergé thimble in Antique Collecting (22). In the magazine it was stated that the thimble (fig 20) had been made in St. Petersburg in the Fabergé workshops before 1896 by workmaster Michael Perchin, gold and has a hard stone top. The thimble has engine turned sides applied with flower-scattered scrolls and the chalcedony stone top is bordered with a diamond set band. This thimble was auctioned by Sotheby’s in Geneva in 1996 (lot 415, 18-19.11.96) and seems to be the same thimble that was auctioned by Christie’s in Geneva in 1981 (lot 32, 17.11.81).

Fig 20

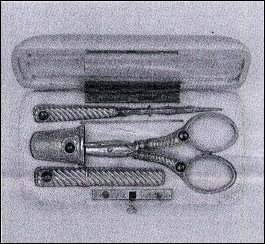

In 2005, Bolland and Marotz in Bremen, Germany (lot 337, 8-9.4.05), auctioned an etui that was attributed to Fabergé (fig 21). It was made of ivory and had an applied crown decorated with diamonds and Almadin (garnet) cabochons. The etui contained a pair of gold scissors, a needle case, a bodkin and a thimble all decorated with Almadin cabochons. The items were marked with KF (Carl Fabergé) in Cyrillic (Kф) and EK, Erik August Kollin, a Fabergé workmaster in St. Petersburg. The etui was authenticated in Germany by Alexander von Solodkoff, an author of several books detailing the works of Fabergé and formerly at Christie’s in London.

Fig 21

A Fabergé thimble (fig 22) by Michael Perchin is in a private collection. It is thought to have been made around 1890 and has the workmasters mark, Fabergé in Cyrillic, the town mark for St. Petersburg and 56 for the gold fineness in the top of the thimble (fig 23). The inventory number (51660) is scratched inside the rim.

Fig 22

Fig 23

It was previously auctioned by Sotheby’s in Geneva in 1996 (lot 394, 13-15.5.96).

We were lucky enough to find our last Fabergé thimble in another private collection (fig 24).

Fig 24 © von Solodkoff

It is a tapering, jewelled, gold and enamel thimble with a domed top set with white quartz. The sides are steel-blue guilloché enamel with a lower two-colour gold border with openwork gold crossed laurel bands, set with three rose-diamonds and three cabochon rubies. The thimble is stamped with the initials of Michael Perchin and was made in St. Petersburg before 1896. There is a scratched inventory number 49223. It is in the original fitted satin-wood case. The satin lining is stamped ‘Fabergé’ in gold Cyrillic letters with the Imperial warrant, and ‘St. Petersburg, Moscow’ in the top. It belonged to Iràne, Princess Henry of Prussia, sister of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna of Russia, and was a gift from another sister, Grand Duchess Elisabeth Feodorovna.

It is clear to us now, as thimble collectors and not as Fabergé experts, that the House of Fabergé and its workmasters, particularly Michael Perchin and Henrik Wigström, did make the occasional thimble. The whereabouts of these thimbles today is largely unknown. Documented evidence only attests to the production of seven thimbles and these were all made by Henrik Wigström. Had Holmes had the advantage of seeing the Wigström album (19) he too would no doubt have been convinced. We suspect many other Fabergé thimbles were lost in the Russian revolution and the majority of the remaining thimbles are in the collections of Fabergé collectors rather than thimble collectors. We rather agree with Holmes that the thimbles shown in figures 2 – 4 are Fauxbergé (23), either because they were not thimbles or because they were not made by Fabergé, and we would add the thimble shown in figure 16 to this list. Three of these thimbles have machine made dimples and the design and quality of the workmanship seems to fall far short of the very high standards set by the Fabergé workshops. Fabergé sometimes bought prefabricated items from other manufacturers and ‘finished’ or decorated them. In this case a workmaster’s mark might have been applied to an item not actually made by Fabergé but it is doubtful whether this took place with these thimbles. Zalkin (24) wrote ‘the name Fabergé has somehow become the generic term for all Russian silver pieces’ and this may explain why so many people seem to have seen a ‘Fabergé’ thimble.

Acknowledgements

We would especially like to thank Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm for answering all our questions so promptly and so authoritatively. Thanks also to Mr Wolf-Dieter Scholz who gave much assistance in finding the references from his wonderful library, and Kieran McCarthy of Wartski, who was able to direct us towards much of the current Fabergé literature. Peter Schaffer from A La Vieille Russie answered all our questions with patience. John Atzbach was very helpful with regard to reference sources and allowed us to reproduce the Fabergé thimble in his collection.

We thank Jeremy Rex-Parkes for identifying and obtaining the Christie’s auction images and Kay Sullivan for permission to reproduce the picture shown in figure 20. Special thanks must go to Alexander von Solodkoff who provided the picture and detailed information relating to the thimble shown in the last figure. We are grateful to Bolland and Marotz in Bremen, Germany, for the image in figure 21.

Christel McCanless provided references to Fabergé thimbles on record in auction catalogues and made helpful suggestions regarding the original manuscript.

Without the help of the above named people this paper would not have been possible.

References

- 1. Lowes, W, and McCanless CL. Lowes and McCanless Index to Fabergé at Auction. Unpublished.

- 2. Holmes EF. Fabergé Thimbles. Thimble Notes and Queries 1989; 2: 8.

- 3. Holmes EF. Thimbles. Gill and MacMillan, Dublin, Ireland. 1982. p. 41.

- 4. von Hoelle JJ. Thimble Collector’s Encyclopedia. Illinois: Wallace-Homestead Book Company, 1986. p. 256.

- 5. Holmes EF. Concerning Fabergé Thimbles. Thimbleletter, 15.5.1988. p.5.

- 6. Holmes EF. A History of Thimbles. London: Cornwall Books, 1985. p. 69.

- 7. Dreesmann C. A Thimble Full. … Utrecht/Netherlands: Cambium, 1983. p. 70.

- 8. Schaffer P, Schaffer PL and Schaffer R. Fabergé, a Loan Exhibition for the Benefit of the Cooper-Hewitt Museum, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Design, April 22-May 21, 1983. A La Vieille Russie, 1983. p. 109.

- 9. Holmes EF. From Our Geneva Correspondent. Thimbleletter, 15.1.1988. p.10.

- 10. Holmes EF. Thimble Notes and Queries 1989; 3: 13.

- 11. Holmes EF. Thimble Notes and Queries 1992; 16: 17.

- 12. Holmes EF. Thimble Notes and Queries 1990; 9: 13.

- 13. Holmes EF. Thimble Notes and Queries 1992; 15: 10.

- 14. TSL Magazine 1992; 4: 5.

- 15. Tillander-Godenhielm U. Personal and Historical Notes on Fabergé’s Finnish Workmasters and Designers in Carl Fabergé and His Contemporaries. A. Tillander, Helsinki, 1980. pp. 28-49.

- 16. Mohr G and Mohr G. Russische Fingerhüte. Rund um den Fingerhut, 1996; 24: 27.

- 17. Mohr G. Gunter Mohr stellt Sammler vor (5). Rund um den Fingerhut, 1991; 13: 33.

- 18. Holmes EF. Thimble Notes and Queries 1992; 14: 6.

- 19. Tillander-Godenhielm U, Schaffer PL, Ilich AM and Schaffer MA. Golden Years of Fabergé: Drawings and Objects from the Wigström Workshop. A La Vieille Russie, 2000.

- 20. Snowman AK. Fabergé: Lost and Found. Thames and Hudson Limited, London, 1993.

- 21. Rund um den Fingerhut, 1997; 25.

- 22. Sullivan K. Thimbles. Antique Collecting, 2004; 39 (2): 24.

- 23. von Habsburg G, von Solodkoff A and Bianchi R. Fabergé: Imperial Craftsman and His World. Booth Clibborn, London, 2000. pp. 385-388.

- 24. Zalkin E. Zalkin’s Handbook of Thimbles & Sewing Implements, 1st. edn. Willow Grove: Warman Publishing Co., Inc., 1985. p. 36.

Appendix

Fabergé and workmaster’s marks mentioned in the text.

| Carl Fabergé | Kф |

| Feodor Afanassiev | фA |

| August Holmström and his son Albert Holmström | AH |

| Erik Kollin | EK |

| Michael Perchin | М.П or M•П |

| Alfred Thielemann | AT |

| Henrik Wigström | H.W. |