Aquamarine Tercentenary Brooch # 4595

(Odom, What Became of Peter’s Dream?

2003, 40-41)

Actress Maria Vedrinskaia,

Recipient of the Brooch –

Hillwood Museum Collection,

Washington, DC.

(Courtesy KinoTeatr.ru)

Russian Art, Icons & Fabergé

November 26, 2012 Christie’s London

Russian Art

November 27, 2012 Christie’s London, South Kensington

An Important Collection of Russian Books and Manuscripts with Imperial Provenance

A 1953 edition of Snowman, A. Kenneth, The Art of Carl Fabergé, in a fine binding with a Victorian gilt bronze and malachite plague by Asprey is included.

November 27, 2012 Sotheby’s London

Russian Works of Art, Fabergé and Icons

Fabergé lace and tortoiseshell fan, apparently unmarked, but probably by Mikhail Perkhin

Mantel Clock by Julius Rappoport

(Courtesy Bonhams London)

Princess Victoria Fan, Harewood Auction

(Courtesy Christie’s London)

Russian Sale

December 5, 2012 Christie’s London

Harewood: Collecting in the Royal Tradition

The Fabergé objects, on view at the auction house during the November’s Russian Art Week, have the royal provenance of H.R.H. The Princess Mary, Princess Royal and Countess of Harewood (1897-1965), only daughter of H.M. King George V and H.M. Queen Mary, and of her son George, 7th Earl of Harewood, who died in 2011.

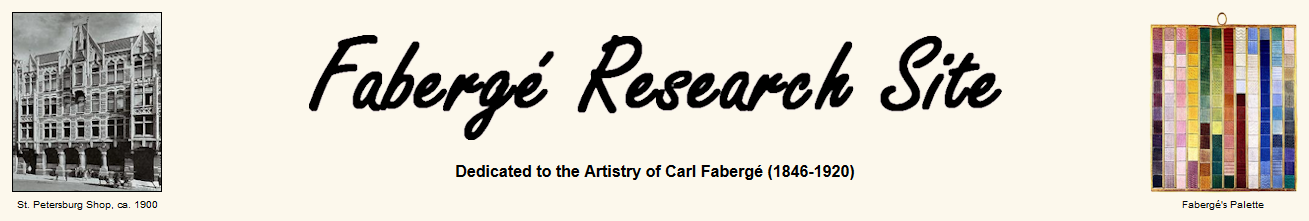

1906 Imperial Swan Egg

(ForbesLife, September 2011, 44)

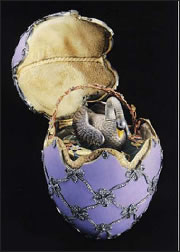

Silver Swan

(Courtesy Bowes Museum)

While surfing the internet, I saw an antique French walking peacock and something just clicked in my mind. I began to wonder, was the French one the source of inspiration for the Fabergé Peacock Egg automaton? Why do they work similarly? Next, some reflections:

- Although the Imperial Peacock Egg design, taken as a whole, is based on the celebrated Hermitage’s Peacock Clock by James Cox, the idea for the walking automaton might be inspired by Le Paon Marchant (The Walking Peacock) from the Parisian firm Roullet et Decamps.

- The bird is not fixed on the tree’s branch, as in the James Cox version, and comparing the sequence of movements between the Hermitage’s automaton and the egg’s automaton, they do not match.

- The animals are almost identical in their conception: The Fabergé peacock movements are similar to those of its French counterpart. However, one difference is that the Roullet et Decamps model stands still when he spreads his tail out and then starts walking again. The Fabergé model keeps walking all the time.

- Both automata are activated by means of a sort of lever located in the lower part of the chest.

- They both share metal supports in the back fulfilling the same function.

- Maison Roullet et Decamps was a reputed automata-maker specializing in the fabrication of jouets mécaniques (mechanical toys). The House of Fabergé is famous for adapting and re-adapting the designs and ideas of others, so it is feasible they saw and studied this automated peacock somewhere and decided to use it as a prototype.

- The idea came from the French company, not in the reverse. The first walking peacock was created by Jean Roullet in 1877 (Archives of Ernest Decamps, modéle n° 100 in their catalogue). It was manufactured until the early 20th century, so by the time the Imperial Peacock Egg was presented in 1908, the afore-mentioned automaton had been on the market for 30 years.

- After some research on the internet, I realized Bernard Pin, co-curator of Mechanical Wonders: The Sandoz Collection exhibition at A La Vieille Russie in 2011, had already suggested a possible connection between the two of them. So needless to say, I am not the first one to propose this hypothesis.

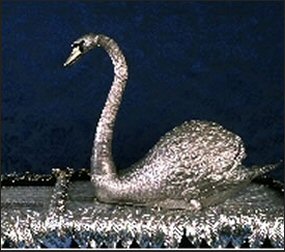

1908 Imperial Peacock Egg by Fabergé

(ForbesLife, September 2011, 44)

In the 1970s, Bernard Pin worked for Gaston Decamps, restoring some of the 19th century automata made by Gaston’s father Ernest in the late 19th century, including the walking peacock. Looking at the internal workings of the 1908 Fabergé egg recently, Pin made a remarkable discovery. If we compare the mechanisms of the Fabergé peacock and the Decamps one, it is exactly the same organization, he says, and notes too that Decamps exhibited his peacock in Moscow around the turn of the century, before work on the Fabergé bird was begun. We have no proof, he cautions, but the implications are clear: Derived from the playthings of nobility, a bourgeois toy became once more a bauble of royalty. (Jonathon Keats, “Miracles in Motion: Clockwork Toys of Philosophers and Czars, Automata Retain Their Power to Astonish”, ForbesLife, September 2011, 44)

At the 1878 Exhibition (Exposition Universelle de Paris), Roullet demonstrated the gardener along with a host of new models including a strutting peacock that spread its tail feathers (…). He was awarded a bronze medal for his effort.

The 1893 Chicago Exhibition report notes (…) that the prolific inventory of the Roullet firm is sold both locally and abroad, bringing in 200,000 francs per year. (Lisa Nocks, The Robot: The Life Story of a Technology, 2007, 41)

As may be judged from an advertisement which appeared during the 1889 Paris Exhibition, the firm was becoming more and more active and prosperous. Roullet states that he exports to foreign countries, and counts among his great specialties bears and other animals that bend over, growl and walk, with their natural cries and noises. (Christian Bailly, Automata: The Golden Age 1848-1914, published in 1987, 116)

1 Roullet et Decamps, Le Paon Marchant (ca. 1890) description and pictures

2 Ibid., ca. 1910 catalog description

3 Ibid., video

4 Ibid., video shows part of the internal mechanism

5 Fabergé walking peacock video beginning at 59 seconds

6 Article by Klaus Lorenz, “Roullet and Decamps Automatons: A Legend Lives On”.

My thanks to editors Christel McCanless and Annemiek Wintraecken for giving me the opportunity to publish this essay.

The 1887 egg is described in a list established in 1889 by N. Petrov, assistant manager to the Imperial Cabinet, as an “Easter egg with clock (Author’s note: Russian has one word for both clock and watch), decorated with sapphires (Author’s note: which the “Blue Serpent Clock Egg” does not have) and rose-cut diamonds”, 2160 r.”

The invoice for the 1895 egg describes it as “Blue enamel egg, Louis XVI style, 4.500 r.” The “Twelve Monogram Egg” (Hillwood Estate, Museum & Gardens in Washington), hitherto dated to 1895 is not in the Louis XVI style. The lacking mention of a clock or watch is not inconsistent with the imprecise descriptions on early Fabergé invoices (Author’s note: The 1895 egg for the young empress does not mention the yellow rose-bud surprise).

In turn, the “Twelve Monograms Egg” now finds a logical slot in 1896 as the missing “Alexander III Egg” described in Fabergé’s invoice as “Blue enamel egg, 6 portraits of H. I. M. Emperor Alexander III with 10 sapphires (Author’s note: which could have decorated the surprise) and rose-cut diamonds”. In a letter from the Dowager Empress to Nicholas II dated March 22, 1896 (Author’s note: Identified by Will Lowes, co-author of Fabergé Eggs: A Retrospective Encyclopedia), she describes her Easter gift as “your ideal egg with the charming portraits of your dear Papa. It is such a beautiful idea, with our monograms (Author’s bold typeface) above it all”.

To complete the triple rocade, Anna and Vincent Palmade (Fabergé Research Newsletter, Winter 2011-2012) have spotted a ribbed gold egg with sapphires and diamonds containing a watch in a Parke Bernet catalogue (March 7, 1964, lot 259), matching an egg in a showcase containing Fabergé objects belonging to the Dowager Empress shown at the St. Petersburg von Dervis 1902 exhibition. This in turn fits A. Petrov’s description (see above), which is left open by the re-dating of the egg in the Monaco Princely Collection.

The hunt for this egg is now on in the USA. It is also the case for an egg which I found many years ago described in a Hammer 1933 Lord and Taylor catalogue (p. 11, cat. 4524): “Miniature Amour holding wheelbarrow with Easter egg. Made by Fabergé”. In 1996, I identified this with the missing 1888 egg in N. Petrov’s list: “Angel pulling a chariot with an egg, 1500r.” for which I have since been hunting high and low in antique shops, yard and garage sales.

(Updates are posted in Exhibitions on the Fabergé Research Site)

The World of Fabergé

Exhibition devoted to Carl Fabergé and other Russian jewelery firms from the end of 19th to the beginning of the 20th century includes 205 objects from the Kremlin Museums and 67 objects from the Fersman Mineralogical Museum, both in Moscow.

October 14, 2012 – January 21, 2013 Detroit Institute of Arts, Michigan

Fabergé: The Rise and Fall, the Collection of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (New Title)

Dr. George and Vivian Dean, owners of the only two extant Fabergé chess sets, are lending them to the exhibition to complement over 200 pieces from the Pratt Collection, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. Information about the chess sets appeared in the Fabergé Research Newsletter, Summer 10.

October 2, 2012 – December 31, 2012 Västra Nylands Landskapsmuseum, Ekenäs, Finland

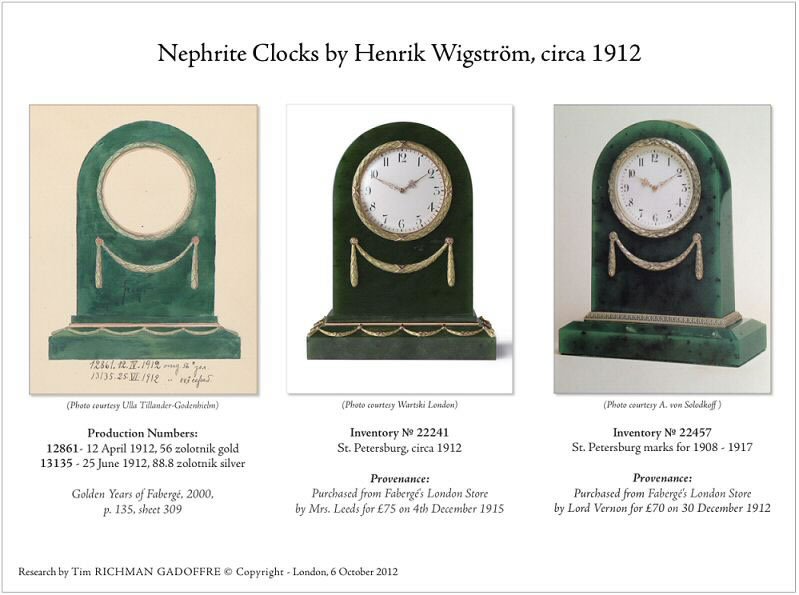

After a highly successful launch of the Henrik Wigström coin by the Mint of Finland, an exhibition in his hometown honors him on his 150th birthday. On display will be a goldsmith’s workbench, photographs from the family album, and facsimiles of drawings from the two Wigström sketch albums. The sketches were published in Tillander-Godenhielm, Ulla, et al., Golden Years of Fabergé: Drawings and Objects from the Wigström Workshop (2000), and in Tillander-Godenhielm, Fabergén suomalaiset mestarit (Fabergé’s Finnish Masters, 2008).

New on the Collectors page through the courtesy of Dr. Géza von Habsburg are biographical details of the American customers at the London sales branch, October 6, 1907 – January 9, 1917. Previously published as Appendix II in von Habsburg, Fabergé in America, 1996, 339-355.

Research contributions on Fabergé eggs published in the 2006-2007 newsletter issues are on the enlarged Eggs page.

Revised Subject Index for the Fabergé Research Newsletter has been compiled.

Fabergé Symposium 2013 at the Houston Museum of Natural Science, Texas

Pre-registration for the Fabergé Symposium at $75 per person. Download the schedule here.

February 14-16, 2013 Columbia University in New York City will be hosting an international conference entitled In Search of Empire: The 400th Anniversary of the House of Romanov. The conference is timely and important because of the current debate over national identity in Russia, the current rewriting of Russian history, and reassessment of the intellectual legacy of Russia during the rule of the Romanovs. Although it is focused on the House of Romanov, the conference – accompanied by an exhibition at the Rare Book and Manuscript Library – will stimulate dialogue across institutional, national, and disciplinary boundaries, and is organized by the Bakhmeteff Archive of Russian and East European Literature and Culture of Columbia University. Contact Tanya Chebotarev.

The Fabergé Collection from the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts will be traveling until the second half of 2015 (a new date), first stop is the Detroit Institute of Arts (opened on October 14, 2012) and then possibly to subsequent venues still under negotiation in North America, Europe, and East Asia. The Fabergé galleries in Richmond will undergo a radical transformation by almost tripling in size. It will enable visitors to see many of the objects in the round, including the five Imperial Easter Eggs in the Pratt Collection.

Fascinating stories and new research with over 500 illustrations about the life and tragic end of the Romanovs (1613-1913) are explored in the interrelationships through marriage between the German, Danish, Greek and Russian families, and their love of travel for family visits. Gift giving and the resulting two-way influence between the countries complete the story.

Russia and Europe

Fabergé: Jeweler of the Last Tsars

in Italian

Fabergé: gioielliere degli ultimi zar (Fabergé: Jeweler of the Last Tsars) published by Silvana Editoriale to coincide with the July 27 – November 9, 2012, exhibition in the restored Reggia Palace, Turin, Italy. (Courtesy Alessia Sturli)

A Fabergé photograph frame presented in 1895 to Allan Bowe, Fabergé’s business partner and manager of the first Moscow shop, has been added to the McFerrin Collection. The gold frame with a dedicatory plaque and the names of his colleagues on the rim of the frame commemorates the opening of a second Fabergé workshop also in Moscow.

Frame with Recipient’s Photograph and Commemorative Plaque with a Strut

in the Form of AB for Allan Bowe

(Courtesy McFerrin Collection, Illustrations © C&M Photographers)

The Russian inscription on the gold plaque:

Многоуважаемому Аллану Андреевичу Бо в память открытия нового магазина на Кузнецком мосту д. Купеческого общества 29 октября 1895 (To the much esteemed Allan Andreevitch Bowe in memory of the opening of the new shop on the Kuznetski Most, Merchant Society 29th October 1895).

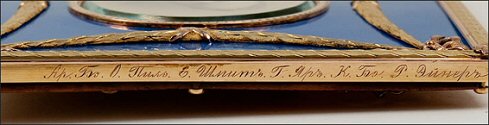

Frame Inscription

(Courtesy McFerrin Collection, Illustrations © C&M Photographers)

- K. Фаберже (Fabergé mark)

- От ювелирнаго отдъеления (From the jewelry department)

- Ар. Бо – О. Пиль – Е. Шмитъ – Г. Яръ – К. Бо – Р. Эйнеръ (Ar. Bowe – O. Pihl – E. Schmidt – G. Yar – K. Bowe – R. Reiner)

- Ф. Анжело – Ю. Гупперцъ – О. Бергъ – Н.Новиковъ (F. Angelo – Yu. Guppertz – O. Berg – N. Novikov)

Arthur Bowe was the brother of Allan Bowe, who opened the London Fabergé branch in 1903 (Ibid., 189)

O. Pihl, master goldsmith who headed the Moscow jewelry shop from 1887-1897, specializing mainly in small jewelry items. During his time the Moscow shop had 38 workmasters and 11 machine tools (Ibid., 228-9)

Charles (K) Bowe, brother to Allan and Arthur Bowe, employed in the Moscow and London shops in an administrative capacity (Ibid., 189)

Also in 1895, a large silver oval tray by Fabergé (formerly in the Forbes Magazine Collection) with the dates 1890 and 1895, an enameled photographic portrait of Allan Bowe, the Roman numeral V, the Russian inscription – To the much respected Allan Andreevich from sincerely grateful employees of the Moscow branch, and the names of the employees of the Moscow branch on the reverse was presented to Allan Bowe. In 1906 he retired from the Odessa branch after 14 years as Fabergé’s partner. For his service, he received a portable oak desk also by Fabergé. (Fabergé Research Newsletter, Spring 2011 and Christie’s Geneva, November 15-16, 1994, Lot 437). Great granddaughter Wendy Bonus in her book, The Fabergé Connection (2010), tells the story of the Bowe family based on family archives and reminiscences.

Frame with a Miniature of Princess Elisabeth

(Hesse: A Princely German Collection, 2005, 193)

Aside from its poignant allure, several aspects of this frame and its provenance invite further inquiry:

- The catalog’s caption dating the frame as 1908-1917

- The miniature portrait’s dating and model, and

- The ongoing search for the symbolism of the enigmatic monogram at the top of the frame.

The dating of the frame (1908-1917) in the exhibition catalog, as well as on the object placard, does create some confusion. The miniature portrait of Princess Elisabeth is signed 1904, and was possibly placed in the frame at a later date. However, further elements of the frame itself emerge, indicating it was probably a gift of memory to Elisabeth’s father in the year following the child’s untimely death in 1903 rather than the later date. Wigström took over the Perkhin Fabergé workshop in 1903 using his own mark, and perhaps a further review of the marks on the frame is needed.

Princess Elisabeth of Hesse (1895-1903) was the only daughter of Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig of Hesse and by Rhine and Princess Victoria Melita of Edinburgh and Saxe-Coburg Gotha. Both parents were grandchildren of Queen Victoria, who arranged the ill-suited match that mercifully ended in divorce when the Queen died in 1901. Victoria Melita “Ducky” was also a granddaughter of Emperor Alexander II of Russia, her mother being Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna, his only daughter.

Princess Elisabeth died suddenly at the age of 8, while visiting her Imperial Russian aunt, the Empress Alexandra, and cousins at the Imperial Hunting Lodge at Skierniewice in Poland. The Princess, rumored to have been poisoned by food meant for the Emperor, was found to have actually died from a virulent form of suppressed typhoid. (Eagar, Six Years at the Russian Court, 1906, 190-94)

Princess Elisabeth with Her Parents Grand Duke

Ernst and Princess Victoria Melita

(Courtesy Wikipedia)

Comparing the monograms on the tie-pins and the frame, the question of a missing precious stone on the latter arises. While close examination of the frame reveals no evidence of a setting between the facing E‘s, it seems a simplistic treatment coming from the workshop of Wigström for such a commission. An element of the monogram more distinguishable on the tie-pins than on the frame is the suggestion of the letter H as a connecting element for the E‘s. As well, if the tie-pin image is rotated 45 degrees, it assumes the shape of the six-pointed star.

Nicholas II Tie-Pin “From Ernie”

(von Solodkoff, The Jewel Album of Tsar Nicholas II, 1997, Item 253, p. 181)

Frame Monogram

(Detail)

- The monogram as representative of the “Two Ella’s” – Princess Elisabeth of Hesse and Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna of Russia, might suggest a case of ‘namesake’ and hence the double E. However, Princess Elisabeth was not her aunt’s namesake, but was named after her great-grandmother Elisabeth of Prussia, much to Queen Victoria’s chagrin. The Grand Duchess Elizabeth was named for her Hessian ancestor, St. Elisabeth of Thuringia.

- The Double E monogram may represent Ernst Ludwig and Elisabeth, father and daughter. Even thirty years after the Princess’ death, her father wrote, My dearest Elisabeth was my only sunshine (Wilson, “From the Hand of God to the Hand of God”, Atlantis Magazine, Vol. 2, No. 2, [2001], 97). In the reminiscences, close family members appear to unite in their consolation of the bereaved father. The recorded gifting pattern of the ‘Diamond Tie Pins’ from Ernst to Nicholas II, and from Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna to her brother Ernst would appear to eliminate the elder Ella from the monogram.

- In a letter from Empress Alexandra in Tsarskoye Selo to her brother Ernst dated 29 February/13 March 1904, a miniature is mentioned. The Empress writes, All our thoughts meet to-day at Rosenhöhe – 12 years already that beloved Papa was taken from us. I thought much of you on the 11th [Princess Elisabeth’s birthday] beside the wee grave wh. [sic] holds what was so dear to us all. I am glad the miniature pleases you, it was done by a simple peasant. (Kleinpenning, The Correspondance of the Empress Alexandra of Russia with Ernst Ludwig and Eleonore Grand Duke and Duchess of Hesse, 1878-1916, 2010, 261) The reference to Zuiev may align with the biographical detail that the miniaturist began work for the Office of His Imperial Majesty in 1904 creating miniatures on ivory. As regards the EE monogram, even if the frame and miniature were a gift from Alexandra to Ernie, it would seem out of norm, that she would include her sister Ella’s initial on the gift when the Princess Elisabeth was not her aunt’s namesake. (Kind reference from Joanna Wrangham)

- Described as a monogram by von Solodkoff, the EE may, indeed be just that, and represent Elisabeth/Ella, the Princess’ name/nickname. (Eagar, Six Years at the Russian Court, 1906, 180) In fact, Princess Elisabeth shared nicknames with two of her Hessian aunts. While sharing the nickname ‘Ella’ with her Russian aunt Elizabeth, she was also known in Hesse as ‘Prinzessin Sonneschein’ (Princess Sunshine), which she shared with her Aunt Alexandra who was known as ‘Sunny’. (Notizen zur Ortsgesschichte, #14, 2003, 22)

- The color of the frame is significant aside from mauve being the signature color of Alexandra. Ernst Ludwig confirmed lilac was Elisabeth’s favorite color. Believing that he was able to understand her from her earliest days, he consulted his daughter on her color preferences when she was scheduled to move into a new bedroom. Her father claimed, she made ‘happy little squeals’ when he showed her a lilac-colored swatch of wallpaper. Confident in his understanding of her desires, Ernie decorated her room in shades of lilac. (Wilson, 91)

Research for the feature story on the Romanov Tercentenary by Roy Tomlin and the monogrammed heart-shaped frame by DeeAnn Hoff led to the online discovery of selections from The Jewel Album of Tsar Nicholas II and A Collection of Private Photographs of the Russian Imperial Family by Alexander von Solodkoff published privately in 1997. Our thanks to Joanna Wrangham from Canada for the new information below.

The original Nicholas II jewel album housed in the Kremlin Museums is reproduced as watercolor facsimiles in von Solodkoff with added explanatory texts in English showing the jeweled gifts received by the Emperor Nicholas II 1889 and 1913.

von Soldkoff, The Jewel

Album of Tsar Nicholas II

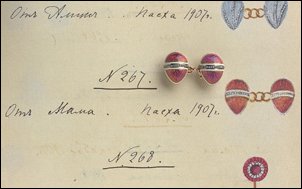

Fabergé Cuff Links with Matching Watercolor Illustration

(Courtesy Wartski)

– “Nickly draws very well and has a lot of taste.” Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich, Nicholas II’s cousin, a well-known poet and writer, July 10, 1894.

– “Nicholas II was not notable for his artistic taste and he had no pretentions to it.” François Birbaum, chief designer with Fabergé’s firm.

Igor Zimin in his book, Tsar’s Money – Income and Expenses of the House of Romanov (2011), suggests the drawings in the original album were done by Baroness Ekaterina (?) Tiesenhausen, the retired lady-in-waiting to Empress Marie Feodorovna. Living in the Freylinskom corridor of the Winter Palace, she did a little “working on part time pictures” for the Emperor. The two entries in the official 1896 Russian Archives (RSHA. F. 525. On. 3. D. 8. L. 37 & L. 109 – Cash Flow Documents and Parish Amounts of His Majesty) state – cufflinks in the book of His Majesty the 3 p. 20 kopecks, and Baroness Tiesenhausen cufflinks in the book of His Majesty 2 Rubles 40 kopecks. Zimin continues, “judging by the manner of writing, it was she who did most of the pictures in the album of the Emperor. Nicholas II from time to time, getting the album and a jewelry chest, quickly tagged by someone, when he received the jewelry gifts”.

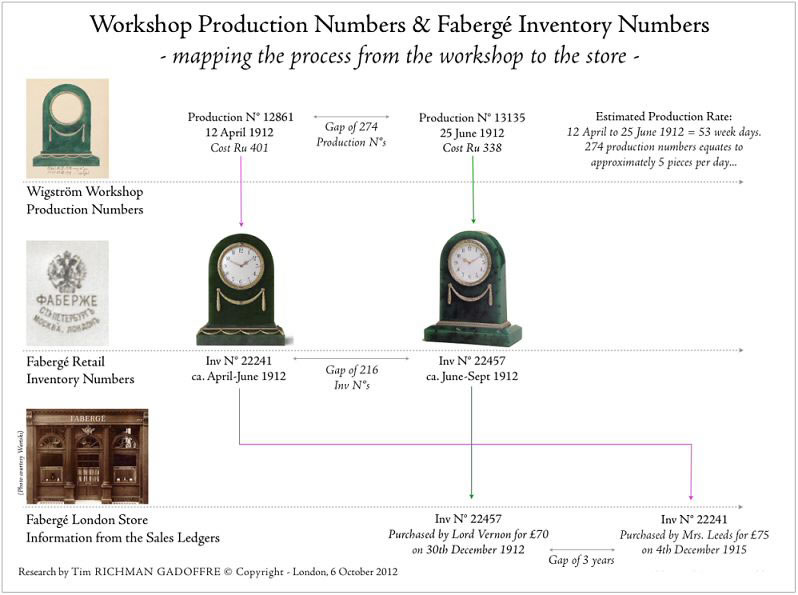

Having handled a magnificent nephrite clock by Henrik Wigström at Wartski’s in London bearing inventory number 22241, I have tracked down its sister. An almost identical nephrite clock bearing inventory number 22457 is based on the same design. Miraculously, there are records for both pieces in the Fabergé London Sales Ledgers, first published by Alexander von Solodkoff’s in Fabergé Clocks (1986) as well as a record of the original design in Henrik Wigström’s album of watercolors in Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm, et al., Golden Years of Fabergé (2000).

The editors were alerted to a discussion on a silver forum about the authenticity of a silver vermeil tea glass holder. We are encouraged by this type of discussion alerting collectors and enthusiasts to potential fakes.

In an archival photograph of the study Tsar Nicholas II in the Winter Palace, a buddha (or maggot) has been spotted which may be the same or similar to the buddha sold at auction (Christie’s London June 11, 2008, Lot 229) and discussed in the Independent. (Courtesy Joanna Wrangham)

Nicholas II Winter Palace Study – Detail

(Courtesy of the Author)